The legendary Harvard professor Michael Porter has contributed several management ideas that are Newtonian in importance and have withstood the test of time and extreme events such as recessions, wars, and technological shifts [1].

The “Three Generic Strategies” is one such idea that simplifies the notion of competitive advantage and gives firms a framework for achieving it.

First introduced in his 1980 book Competitive Strategy [2], Porter argued that there are three primary types of (sustainable) competitive advantage firms can hope to secure:

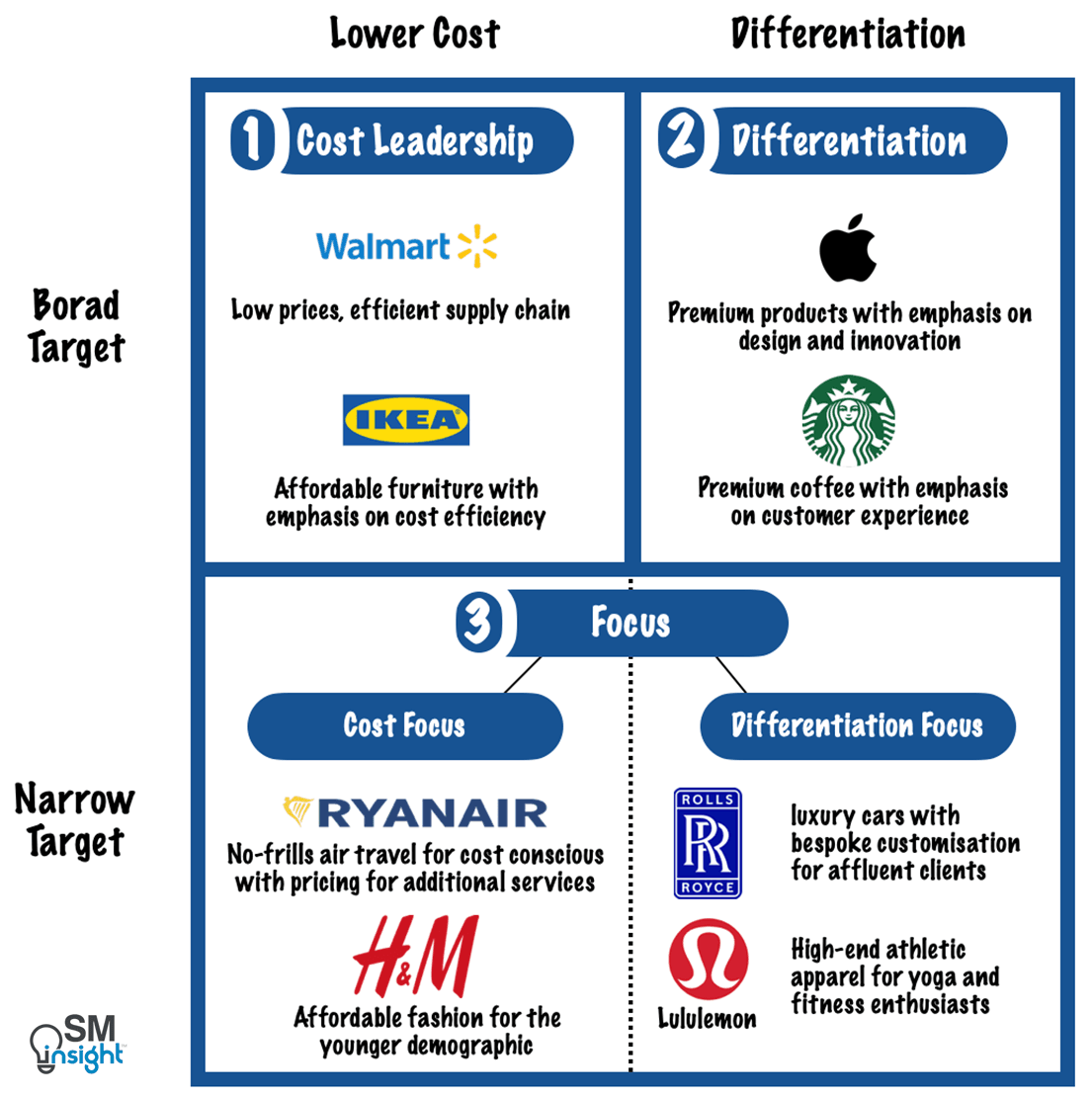

- Cost Leadership: become the industry’s most cost-effective producer and provide products/services at the most competitive prices to eventually capture a majority market share.

- Differentiation: Make products or services different from and more attractive than the competition – differences can be based on factors such as product design, brand image, technology, features, customer service, etc.

- Focus Strategy: Concentrate on a narrow market segment and tailor offerings to the needs of that market, thus achieving dominance in that niche.

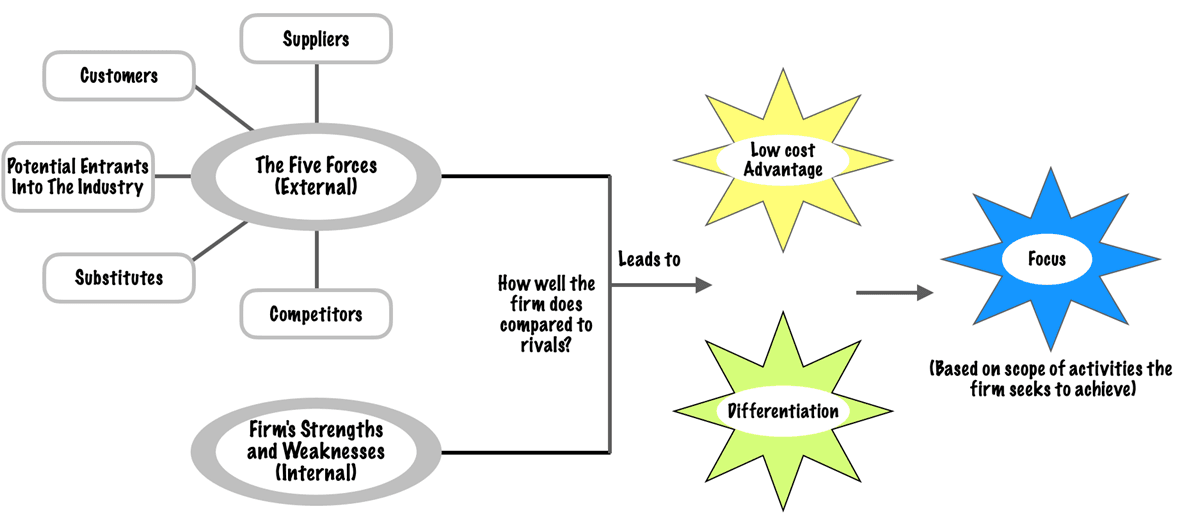

While Porter’s popular “Five Forces Model” [4] emphasizes factors external to a firm (customers, suppliers, substitutes, potential entrants into the industry, and competitors), the three generic strategies consider internal factors.

Cost and differentiation are fundamental competitive advantages

The fundamental basis of above-average performance is having a sustainable competitive advantage. Every firm has several strengths and weaknesses. Its competitive advantage is also influenced by the industry structure in which it operates and its ability to cope with the five forces.

But all of this essentially boils down to two basic types of competitive advantage: low cost and differentiation.

These two basic types of competitive advantage, combined with the scope of activities for which a firm seeks to achieve them, lead to three generic strategies for achieving above-average performance in an industry: Cost Leadership, Differentiation, and Focus.

The focus strategy has two variants: Cost focus and Differentiation focus.

Because each strategy involves a fundamentally different route to competitive advantage, implementing them requires total commitment. A firm must choose the type of advantage it seeks and the scope within which it will attain it.

Firms that aim to be “all things to all people” walk the path of strategic mediocrity and deliver below-average performance – they end up with no competitive advantage at all.

1. Cost Leadership

Achieving cost leadership requires aggressive construction of efficient-scale facilities, vigorous pursuit of cost reductions from experience, tight cost and overhead control, avoidance of marginal customer accounts, and cost minimization in areas like R&D, service, sales force, advertising, etc.

A managerial focus on cost control is necessary to achieve these aims. In firms that pursue low-cost leadership, being low-cost relative to competitors is the theme that dictates the entire strategy, quality, service, and all other areas.

Firms that achieve low-cost leadership reap several benefits:

- The firm’s cost position is a defense against rivalry because it can still earn returns after its competitors have exhausted their profit margins through rivalry.

- It defends against powerful buyers because a buyer can exert power only to drive down prices to the level of the next most efficient competitor (and in this case, there are none).

- It also defends against powerful suppliers by providing more flexibility to cope with input cost increases compared to rivals.

- Cost leadership often results from scale economies or cost advantages unique to a firm, which is difficult to replicate for new entrants. Hence, it serves as a substantial entry barrier, protecting the firm from the threat of new entrants.

- A low-cost position places the firm in a favorable position vis-à-vis substitutes relative to its competitors in the industry.

Cost leadership protects a firm against all five competitive forces. Less efficient rivals suffer first under competitive pressures.

Achieving cost leadership means exploiting all sources of cost advantage. Such firms typically sell standard, no-frills products/services and emphasize reaping scale or absolute cost advantages from all sources. They generate above-average returns at comparable or slightly lower prices than rivals.

However, a cost leader cannot ignore the bases of differentiation. If buyers do not perceive products or services as comparable, a cost leader would be forced to discount prices, thus nullifying the benefits of a favorable cost position.

For example, when Texas Instruments (TI) introduced the first sub-$20 LED digital watch in 1966, drastic discounts led to these watches (and those of competitors) becoming commoditized. Several digital watchmakers went out of business, and TI had to pull out of the watch business by 1980 due to plummeting revenues [5].

For sustained competitive advantage, a cost leader must achieve parity and proximity:

Parity allows a cost leader to translate cost advantage directly into higher profits than competitors. Proximity means the price discount necessary to achieve an acceptable market share does not offset the cost advantage, thus leading to above-average returns.

The strategic logic of cost leadership requires that a firm be the cost leader, not one of several firms vying for this position. When there is more than one aspiring cost leader, rivalry is usually fierce, and the consequences on profitability can be disastrous.

2. Differentiation

A firm that follows the differentiation strategy seeks to be unique in its industry along certain dimensions that buyers widely value and perceive as important. It uniquely positions itself to meet those needs and is thus rewarded for that uniqueness with a premium price.

Differentiation is peculiar to each industry and can be based on the product itself, the delivery system by which it is sold, the marketing approach, or a broad range of other factors.

Apple differentiates its products through design – great design principles are pervasive in Apple’s DNA. In 2021, the brand had a 23% market share in smartphones by numbers, yet it took 75% of the industry’s profits and 40% of revenue [6] [7].

Coca-Cola’s differentiation strategy is evident in its brand value, making its products the most familiar names in the world. Over the past decade, it has consistently maintained a market share close to 50% [8] [9].

Similarly, the reliability of Caterpillar products in the Construction & Mining Machinery Industry has created a differentiation that translates into a market share close to 66% [10] [11].

As seen in the above examples, firms capable of achieving and maintaining differentiation outperform their industry peers. They command premium prices that offset the additional costs associated with being distinctive.

However, such firms cannot entirely ignore their cost position because a markedly inferior position will nullify the effect of premium pricing. They must aim for cost parity or proximity relative to their competitors by reducing costs in all areas that do not affect differentiation.

A differentiation strategy also requires that a firm choose attributes that distinguish it from rivals. To expect a premium, a firm must truly be unique at something or be perceived as unique.

In contrast to cost leadership, however, more than one successful differentiated firm can exist in an industry, provided several attributes are widely valued by buyers.

3. Focus

Firms pursuing a focus strategy select a segment or group of segments in the industry and optimize their strategy to serve them to the exclusion of others. They seek to achieve a competitive advantage in their segments of choice even though they do not possess an overall competitive advantage.

This strategy has two variants: cost focus and differentiation focus. In cost focus, a firm seeks a cost advantage, while in differentiation focus, it seeks differentiation (both within a narrow or a single target segment).

In both these variants, success rests on how the needs ofthe focuser’s target segments differ from those of the rest of the industry. The target segments must either have buyers with unusual needs or the production and delivery system that best serves them must differ from that of other industry segments.

Such segments are (usually) underserved by broadly targeting competitors who treat them like the rest of the industry’s consumers.

While cost focus exploits differences in cost behavior (Ryan Air), differentiation focus exploits the special needs of buyers (Rolls Royce). Both operate in certain segments.

A differentiation-focused firm looks for segments with special needs and better meets them to realize higher profit margins (e.g., Rolls Royce sometimes pockets more profits from customization than from selling the car itself) [12].

Differentiation-focus differs from overall differentiation, where a firm bases its strategy on widely valued attributes (e.g., Mercedes Benz).

A focuser firm thus achieves a competitive advantage by dedicating itself exclusively to a particular segment. While the breadth of the target can vary in degree, the essence of focus is the exploitation of a narrow target’s differences from the rest of the industry.

However, a narrow focus by itself is not sufficient for above-average performance. A focuser must also be able to take advantage of suboptimization (either in cost or differentiation).

In meeting the needs of a particular segment, broadly targeting competitors may either be underperforming (which opens opportunities for differentiation focus) or overperforming (which opens opportunities for cost focus).

A focus firm pursuing either strategy can become an above-average performer, provided the segment’s structural attractiveness (profitability) is sound.

Like differentiation, multiple sustainable focus strategies are often possible in an industry, provided firms target different segments.

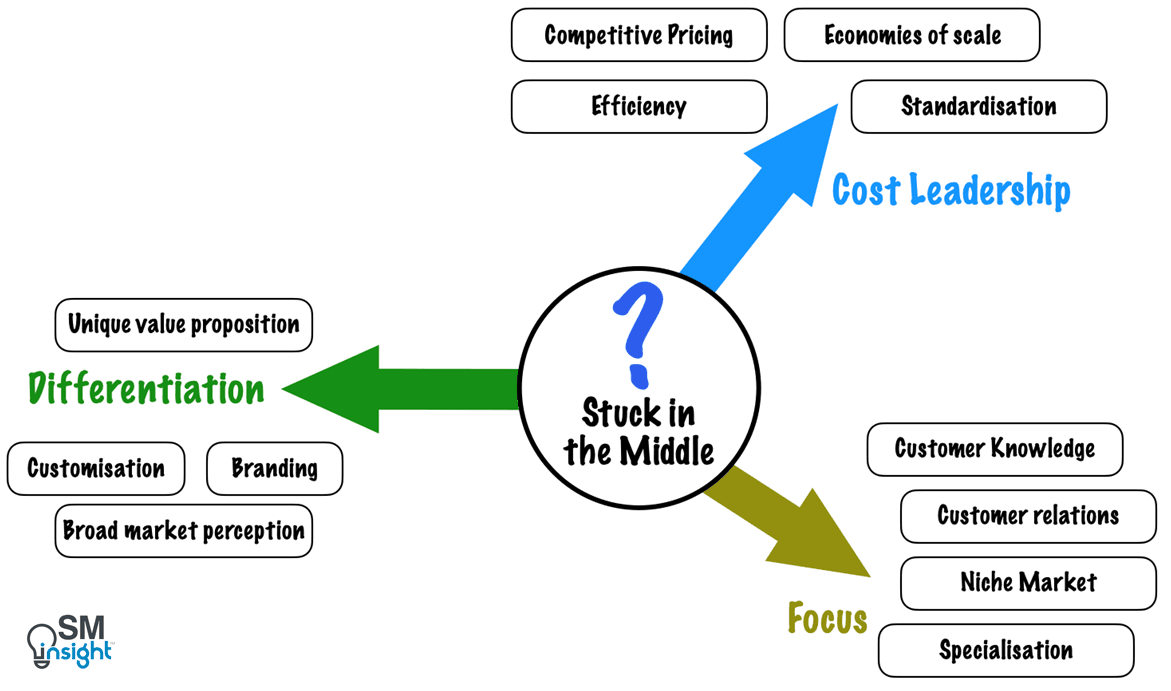

Stuck in the middle

Achieving different types of competitive advantage usually requires actions that are generally inconsistent with each other. Firms that do not choose how to compete get stuck in the middle. They try to achieve a competitive advantage through every means but achieve none.

Sometimes, successful firms compromise their generic strategy for the sake of growth or prestige. This can have disastrous consequences.

For example, in 1996, McDonald’s sunk $200 million in its marketing campaign to introduce Arch Deluxe, a “luxury-fast-food” burger. McDonald’s later learned that its customers weren’t attracted to the brand for luxury (focus) but for convenience (no frills / low cost). Arch Deluxe failed miserably [13].

It is rare for a firm stuck in the middle to earn attractive profits. It is possible only if the industry’s structure is highly favorable or the firm is fortunate enough to have competitors that are also stuck in the middle.

While such situations may exist when the industry is new, eventually, rivals achieve one of the generic strategies, and the performance gap between firms with and without a generic strategy widens. Ill-conceived strategies that worked during rapid growth begin to fail.

Porter also warns that the temptation to blur a generic strategy and become stuck in the middle is particularly great for a focuser firm once it has dominated its target segments.

Because focus deliberately limits potential sales volume, success can lead a focuser to lose sight of the reasons for success and compromise its focus strategy. A firm is usually better off finding new industries to grow where it can use its generic strategy again or exploit interrelationships instead of pursuing cost focus.

Perusing more than one generic strategy

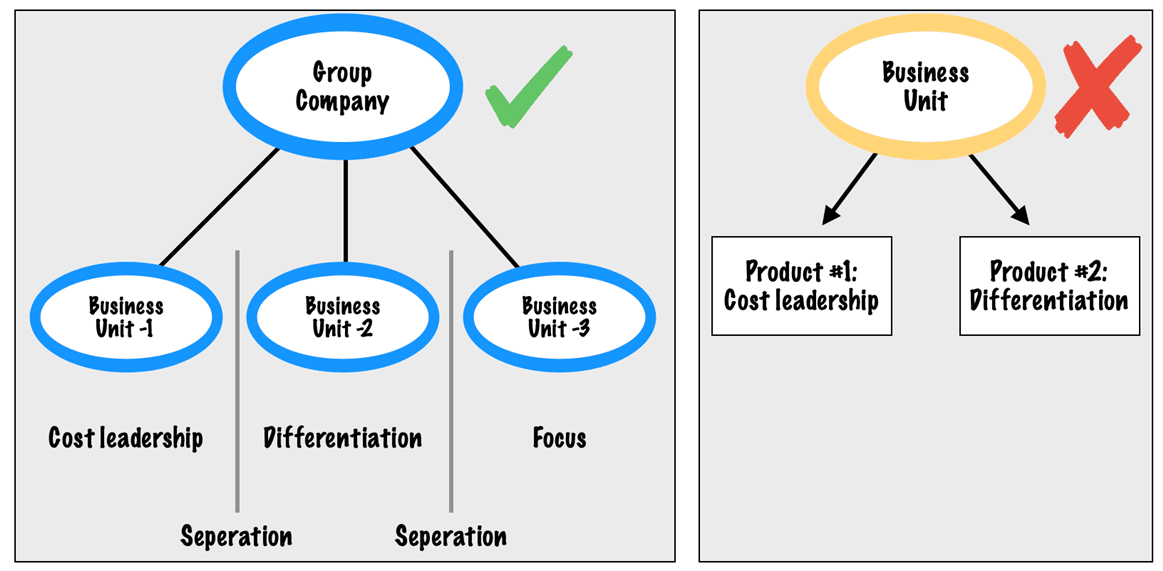

Because each generic strategy takes a fundamentally different approach to creating and sustaining competitive advantage, a firm must make a choice.

The benefits of optimizing the firm’s strategy for a particular target segment (focus) cannot be gained if a firm is simultaneously serving a broad range of segments (cost leadership or differentiation).

However, firms may be able to pursue multiple generic strategies through separate business units within the same corporate entity:

In such a case, the separation between units is crucial. Without it, firms risk taking a sub-optimized approach due to the spillover of policies and culture from one unit to another, eventually leading to being stuck in the middle.

Toyota is an example of success. The carmaker focuses on cost leadership by offering reliable, fuel-efficient, and affordable vehicles for the mass market. Toyota also owns the Lexus brand, which follows a differentiation strategy and targets the luxury/premium segment.

P&G takes a cost leadership approach in the detergent market with Tide but takes a focus-differentiation approach with its Olay line of skin care products in the beauty industry [14].

Similarly, Hilton takes a cost leadership approach with Garden Inn, offering value-for-money accommodation for cost-conscious travelers, but takes a focus-differentiation approach with Waldorf Astoria, offering luxury accommodations for high-end travelers.

In all these cases, however, there is a clear separation between these units within the group.

Risks and vulnerabilities of generic strategies

A generic strategy does not lead to above-average performance unless sustainable. To be sustainable, a firm must be able to defend its competitive advantage and resist erosion by competitive behavior or industry evolution.

Each generic strategy involves risks and vulnerabilities:

Cost Leadership Risks:

- Competitors imitate or achieve similar / lower costs.

- New technology nullifies cost advantages by making processes efficient and cheaper.

- Proximity is lost – low price no longer provides meaningful market share.

- Rising inputs, labor, or resource costs squeeze profit margins and undermine the low-cost position.

Differentiation Risks

- Competitors start offering products that are (buyers perceive are) similar, thus diluting the perceived uniqueness and value proposition.

- The value of differentiation decreases in the eyes of the buyers (this could be due to technology shifts, changing trends, better substitutes, etc.).

- Cost proximity is lost – it is no longer possible to maintain differentiation within reasonable cost limits.

Focus Risks

- Competitors imitate the focus strategy.

- Target segment becomes structurally unattractive (structure erodes / demand disappears).

- Broadly targeting competitors overwhelm the segment. The gap between the focus segment and other segments narrows, or the advantages of other segments increase.

- New focusers further sub-segment the industry.

In most industries, the three generic strategies can profitably coexist if firms pursue different ones or select different bases for differentiation or focus.

However, when two or more firms pursue the same generic strategy on the same basis, the result can be a protracted and unprofitable battle. Worst still, the industry structure quickly erodes when several firms vie for overall cost leadership.

Thus, competitors’ past and present choice of generic strategies impacts a firm’s available choices and the cost of changing its position.

Generic strategy and the industry evolution

Changes in industry structure can also affect the basis on which firms establish their generic strategies, often creating risks (discussed earlier).

For example, in the early history of automobiles, firms followed a differentiation strategy to produce expensive touring cars. In 1908, technological and market changes allowed Henry Ford to introduce the Model T, which changed competition rules by adopting a classic cost leadership approach [15].

By the late 1920s, economic growth, technological advancements, and an increased acceptance of automobiles allowed General Motors to reshape the same industry once more. GM adopted a differentiation strategy, offering diverse features and premium-priced models [16].

By the 1930s, GM had overtaken Ford as the dominant auto industry leader – a title it would retain for almost 70 years [17].

Generic strategies and Strategic planning

Because competitive advantage is critical to achieving superior performance, generic strategies must become the cornerstone of a firm’s strategic plan. It must set the framework for actions in each functional area.

Porter cautions against the following flawed approaches to strategic planning:

- Strategic plans that merely contain a list of actions and do not articulate a firm’s competitive advantage or how it aims to achieve it.

- Basing strategic plans on projections of future prices and costs. This approach is often inaccurate because it lacks a deeper understanding of industry structure and competitive advantage, which ultimately determine profitability (regardless of actual prices and costs).

- Categorizing business units as “build,” “hold,” “harvest,” etc. While such terms are good for resource allocation, they are misleading strategy names as they do not outline the organization’s path to competitive advantage. They are outcomes of successful or failed generic strategies, not the strategies themselves.

- Treating acquisition and vertical integration as strategies – these are not strategies for competitive advantage but means for achieving them.

- Using market share to describe a business’s competitive position or setting goals in terms of market share – while relevant, market share is not a cause but an effect of competitive advantage. Market leaders may not always enjoy the best performance.

Thus, Porter’s Three Generic Strategies provide a sound framework for firms to build competitive advantage. Several studies have established a strong positive correlation between Porter’s three generic strategies and competitive advantage [18]. Whether through cost leadership, differentiation, or focus, the framework guides firms in making strategic choices to achieve superior performance and avoid mediocrity.

Sources

1. “Biography ( Michael Porter)”. Harvard Business School, https://www.isc.hbs.edu/about-michael-porter/biography/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed 15 Feb 2025.

2. “Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors”. Michael E. Porter, https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=195. Accessed 15 Feb 2025.

3. “The Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance”. Michael E. Porter, https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=193. Accessed 15 Feb 2025.

4. “Porter’s Five Forces”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/porters-five-forces/. Accessed 15 Feb 2025.

5. “The Golden Age of Texas Instruments Consumer Gadgets”. Pc Mag, https://www.pcmag.com/news/the-golden-age-of-texas-instruments-consumer-gadgets. Accessed 16 Feb 2025.

6. “3 Ways Apple Sets Itself Apart from the Competition”. Time, https://techland.time.com/2012/07/30/3-things-that-set-apple-apart-from-the-competition/. Accessed 17 Feb 2025.

7. “The Cost of Making an iPhone”. Investopedia, https://www.investopedia.com/financial-edge/0912/the-cost-of-making-an-iphone.aspx. Accessed 17 Feb 2025.

8. “Research on Competitive Strategy of Coca-Cola Company”. Xueyao Guo and Manyu Wen, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357612843_Research_on_Competitive_Strategy_of_Coca-Cola_Company. Accessed 17 Feb 2025.

9. “Coca-Cola Company’s market share in the United States from 2008 to 2022”. Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/225388/us-market-share-of-the-coca-cola-company-since-2004/. Accessed 17 Feb 2025.

10. “CAT’s vs. Market share relative to its competitors, as of Q1 2024”. CSI Market, https://csimarket.com/stocks/competitionSEG2.php?code=CAT. Accessed 17 Feb 2025.

11. “SWOT Analysis of Caterpillar 2023”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/swot-analyses/caterpillar-swot-analysis/. Accessed 17 Feb 2025.

12. “A $10bn car? The trend for hyper-personalised cars gains momentum”. Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/980a2b48-bfbe-4f4b-a606-7d78fd3d5b21. Accessed 17 Feb 2025.

13. “The Rise And Fall Of The Arch Deluxe, McDonald’s Most Ambitious Failure”. Ranker, https://www.ranker.com/list/mcdonalds-arch-deluxe-failure/kellie-kreiss. Accessed 17 Feb 2025.

14. “A Deep Dive into Marketing Strategies of Tide”. The Brand Hopper, https://thebrandhopper.com/2024/04/21/a-deep-dive-into-marketing-strategies-of-tide/. Accessed 17 Feb 2025.

15. “Building Strategy on the Experience Curve”. Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/1985/03/building-strategy-on-the-experience-curve. Accessed 19 Feb 2025.

16. “The Cultural Antagonisms of Engineering and Aesthetics in Automotive History”. David Gartman, http://www.autolife.umd.umich.edu/Design/Gartman/D_Casestudy/D_Casestudy3.htm. Accessed 19 Feb 2025.

17. “How Alfred Sloan and GM changed American history”. Bell Performance, https://www.bellperformance.com/blog/general-motors-interesting-history-vision. Accessed 19 Feb 2025.

18. “THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PORTER’S GENERIC STRATEGIES AND COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE”. George Ouma (International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management), https://ijecm.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/3666.pdf. Accessed 19 Feb 2025.