The Theory of Change (ToC) is a structured approach used in program planning and evaluation. It seeks to explain what impact is created by a programme or system, and how that impact was generated.

ToC articulates how the change will happen, and as a result, influences the plan for investing the time and resources to contribute to that change. It is a helpful tool for developing solutions to complex social problems.

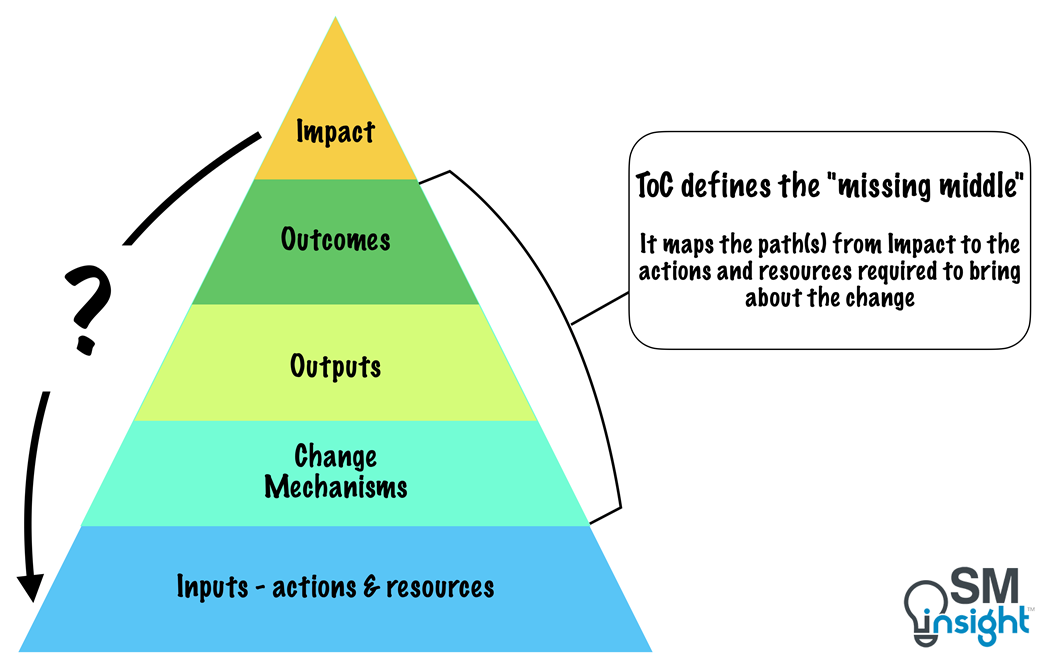

ToC helps to see the “missing middle” between the impact and the ground-level actions and resources

ToC has its roots in a number of disciplines, including programme analysis, logic planning models and informed social practice and has been widely applied in programme evaluation, goal setting and strategic planning.

Today, ToC is a fundamental component of any large-scale social change effort and has been used by government, as well as philanthropic institutions worldwide including the United Nations[1], World Bank[2], USAID[3], and UK Department for International Development[4].

A clear ToC helps strengthen strategies and maximize results by identifying the work to be undertaken, the expected signals of progress and the presumed or possible pathways to achieving desired goals that reflect beliefs, working assumptions or hypotheses.

ToC Overview

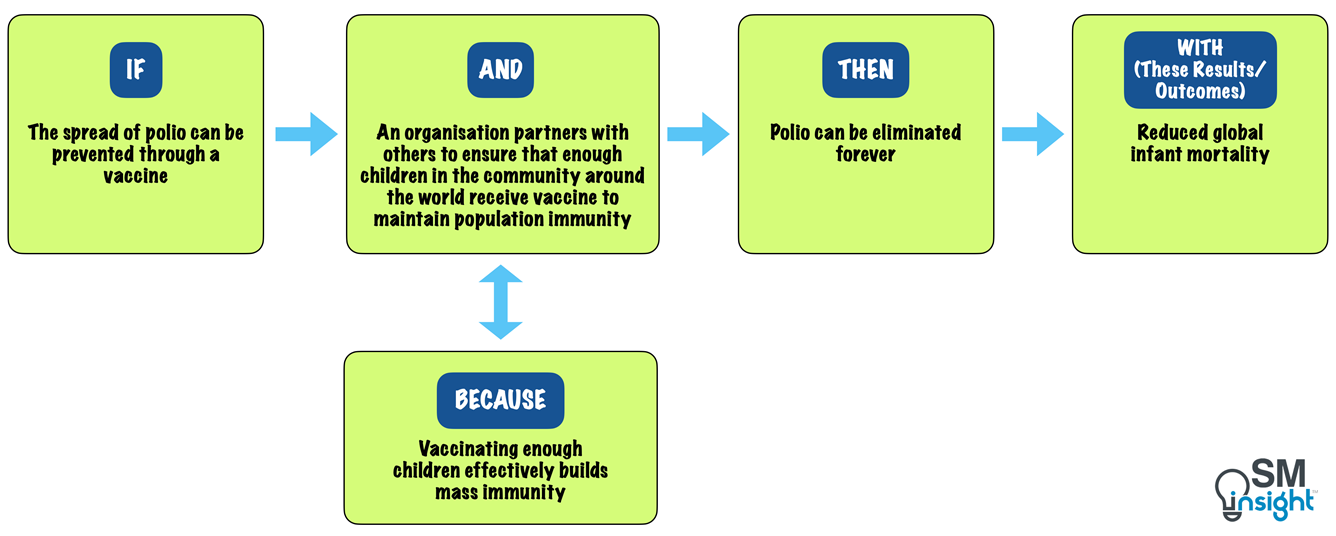

In its simplest form, a ToC is a series of logically linked statements that communicate an organization’s (or initiative’s) focus, plan, and ideal outcome in a succinct, comprehensible way.

For example, a simple ToC from the health sector might look like this:

This is a high-level ToC that does not include the technical factors related to disease elimination. Even implementing the “AND” alone can be a very complex undertaking. Yet, ToC captures the essence of the problem, the proposed solution, and the desired outcome.

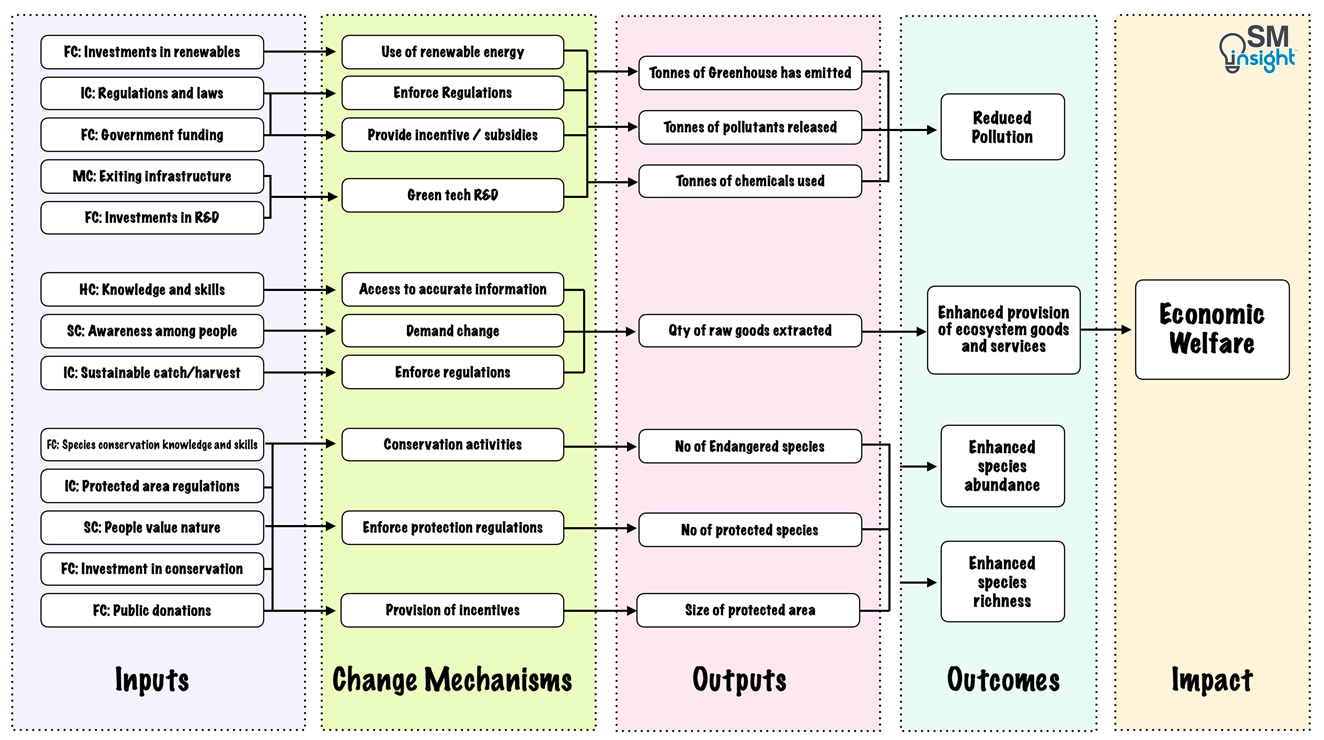

More complex ToC(s) take the form of a diagram or flow chart depicting the relationships between the different components of the system. It also includes a narrative description of how the components of the diagram are linked.

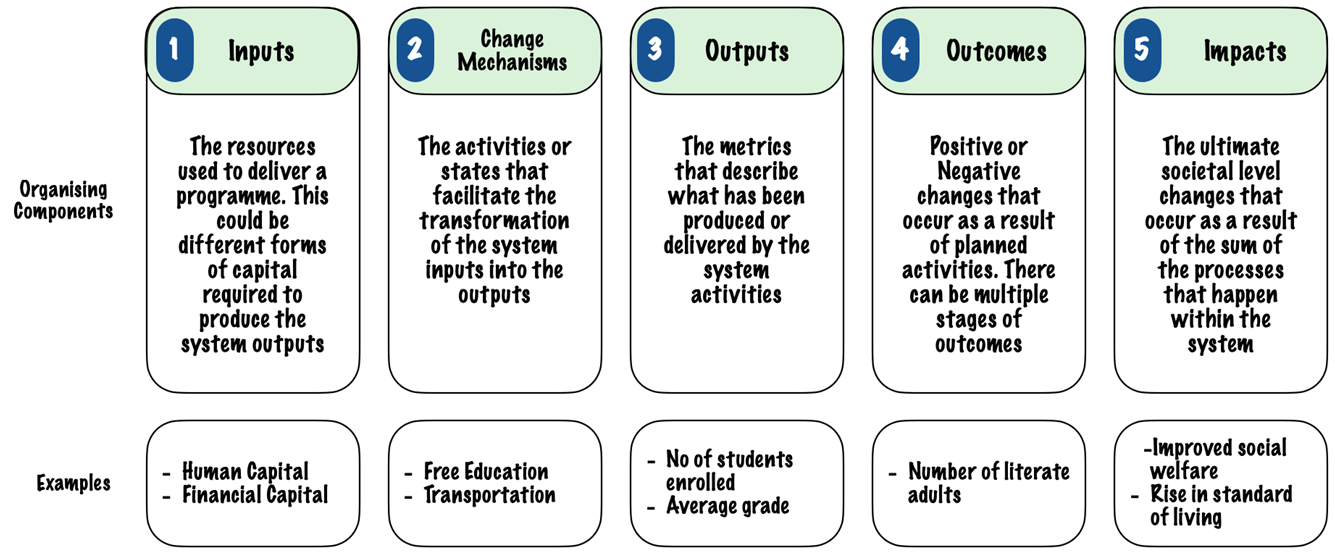

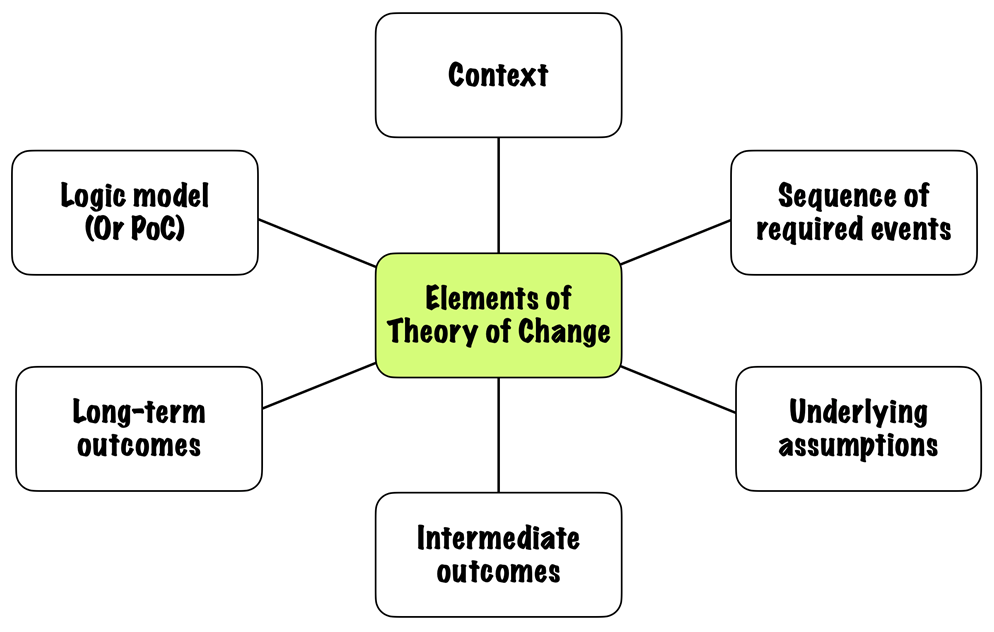

The ToC framework is structured around five components:

ToC diagrams are read from left to right or top to bottom. The first column of boxes are the inputs to the system that are required to create the change mechanisms in the second column. These change mechanisms then influence the outputs, which in turn influence the outcomes, and finally, the impact:

Benefits of ToC

ToC is intended to be a helpful and practical tool to improve the design, implementation, and assessment of programs. The following among the many of its benefits particularly standout:

It helps create a foundation for a grant-strategy

Every social change program requires funding and grant support. ToC helps better articulate the positive impact of a program with evidence, logic, and structure. It brings credibility in the eyes of the funders, board members, and other stakeholders. Creating ToC up front also ensures clarity in the organization’s overall strategy and avoids miscommunication.

It tests assumptions

Challenging assumptions is a built-in requirement of the ToC development process. The resulting reflection provokes hard conversations among (or within) various organizational stakeholders. Addressing these inevitable conversations early on allows for healthier processing within an organization and strengthens the team’s buy-in.

It opens communication among team members

Creating a ToC raises new questions for stakeholders to consider while developing a strategic plan or evaluation. The resulting dialogue leads to clearer processing, the opportunity for a more participative collaboration, and better ownership. ToC also helps stakeholders develop a unified understanding of how the organization believes change will occur.

It sharpens messaging

As ToC articulates how a change will take place in a most comprehensive and succinct manner, it enables external communication and makes it easier to share ideas and action plans with external stakeholders.

It creates a pathway for systems change

By making it easier to explain the overall flow, ToC opens possibilities for shared action with fellow collaborators. This, in turn, helps drive systemic change by highlighting the key areas to focus on and where support is needed.

It serves as a guide to measuring success

ToC serves as a guiding map to track progress, achievements, and failures and helps determine efficacy. This aids in developing achievement measures, key performance indicators, and strategic implementation decisions.

It provides a framework for decision-making

ToC helps in tactical decision-making around investments of time and resources at all levels of program management.

Steps in a ToC Evaluation

ToC diagrams are constructed using the backward mapping approach, starting with the impact, and capturing the expectations of the change. Stakeholders focus explicitly on the following high-level steps while reflecting on the contextual factors that influence their decision-making:

Step 1: Determine the vision or the impact

The focus of this step is on the long-term vision of an initiative and is likely to relate to a timescale that goes beyond the timeframe of the initiative. ToC participants discuss, agree on, and get specific about, the long-term goal or goals. It is important to set a good, clear vision as the quality of the rest of the theory hinges on doing this right.

Step 2: Determine outcomes

Having agreed on the ultimate aim of the programme, stakeholders then consider the necessary outcomes that will be required by the end of the programme if such an aim is to be met in the longer term.

Step 3: Determine outputs

In this step, stakeholders articulate the types of outputs that will help achieve the specified outcomes. They work backwards to construct a framework that tells the story that is appropriate for the purposes of planning.

Sometimes, this might require much more detailing as stakeholders may want to identify the “root” causes of the problem they hope to resolve. In other cases, the map will illustrate three to four levels of change, which displays a reasonable set of early and intermediate steps toward the long-term vision.

Step 4: Identify change mechanisms

At this stage, those involved with the programme consider the most appropriate activities or interventions required to bring about the required change. These are the change mechanisms – program activities, policies, and/or other actions that would be required to bring about the outcomes on the map.

Step 5: Determine resources and inputs

In this final step, stakeholders consider the resources that can realistically be brought to bear on the planned interventions. These will include staff and organizational capacity, the existence of supportive networks and facilities as well as financial capability.

Practical tips to developing a ToC

A good theory must ensure programs are delivering the right activities for the desired outcomes. This requires the key elements of a ToC to come together:

To develop an effective ToC, the following practical tips and tools have proven effective:

1. Identifying outcomes

Most social change agents work to bring about a complex set of changes that are easier to discuss with terms that are multi-dimensional, but such terms are of little use in practice.

For example, terms such as “improved family functioning” or “integrated services for youth” sound good in conversation but are too vague to serve as a foundation for ToC.

This can lead to a lack of clarity as concepts remain unpacked, making it harder to build a case for getting the job done or proving that it was done well. Thus, before beginning to create a ToC, outcomes need to be “unpacked” into specifically defined components because:

- Vague outcome statements lead to fuzzy thinking about what needs to be done to reach them.

- They sabotage the ability to build a consensus about what is important.

- They make it difficult to figure out how to develop measurement strategies to tell when and if they have been achieved.

Processes and tools to identify outcome

The session to identify the long-term outcomes must be conducted with a democratic and inclusive tone while ensuring participation from key stakeholders in the initiative. Ideally, the group size should be less than ten.

The following processes and tools are useful:

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is one of the easiest ways to reach a consensus on the various dimensions captured by a long-term goal. The process of constructing the definition of the long-term goal can then follow.

The following questions are a good starting point for thinking about long-term outcomes:

- What are the ultimate goals of the program or initiative?

- What should a successful program look like? – definition

- What are the expectations of the investors and program participants?

- Given what is known today, what will be different for the community in the long term due to a successful change?

Ideas generated during brainstorming must be captured, sorted, and displayed for everyone to see. The use of Post-it notes is one effective way to go about the process.

Sharing

This step requires that the participants read each of the notes for a few minutes or, alternately, read each note to the group. Often, the major ideas repeat with slightly different wording, and a few outliers emerge.

The ideas can then be sorted into categories. Ones that repeat should be discussed while the wording that best sums up the concept can be finalized through voting.

Refining

Refining is the process of carefully evaluating and organizing ideas that emerge during brainstorming. A facilitator, typically in a group setting, categorizes these ideas, deciding where each fits in relation to the overarching goal.

The refining process must ensure that only relevant and valuable ideas contribute to the overall strategy.

Voting

Voting is the best way to democratically decide which idea(s) reflects the group’s long-term goal. It is ideal when there are a few topics, or to sense what each of the participants see as the “group think” on the long-term goal.

Voting should continue until the group has landed on a set of ideas that reflect a consensus on the ultimate goal of the initiative.

2. Developing pathways to change

Pathway of Change (PoC) is a map that illustrates the relationship between actions and outcomes and shows how outcomes are related to each other over the lifespan of the initiative.

While the PoC map is an important feature of ToC, it is not the whole thing. PoC map alone cannot tell the whole story of a program theory. It is a skeleton on which successive waves of detail are added to create a compelling ToC.

Constructing a PoC is the most time-intensive step and the centerpiece of the ToC development work. Participants must stress the following:

- The PoC map must depict the relationship among nouns – only outcomes such as results, accomplishments, states, changes, etc.

- Participants are often inclined to focus on what they “must do” or what “must be done” to others in the process of creating the change. This trap can be avoided by reminding participants that verbs are not allowed just yet.

- The PoC map links together the “things” that must be in place for the long-term outcome to exist.

This can get confusing. Referring to examples is a good way to ensure participants understand the complete set of necessary and sufficient preconditions (requirements, ingredients, building blocks, etc.) that are required to achieve the long-term goal. - As the PoC map is developed using the “backwards mapping” process, the group should imagine starting at the end of the initiative and walking backwards in their minds to the beginning.

Processes and tools to develop PoC

While there is no scripted way to develop a PoC, the key task is to get the team to answer the question:

“What are the necessary and sufficient preconditions for the chosen outcome to occur?”

This process needs to be repeated as the team moves backward while mapping the change pathway. The following sequence is proven to be effective:

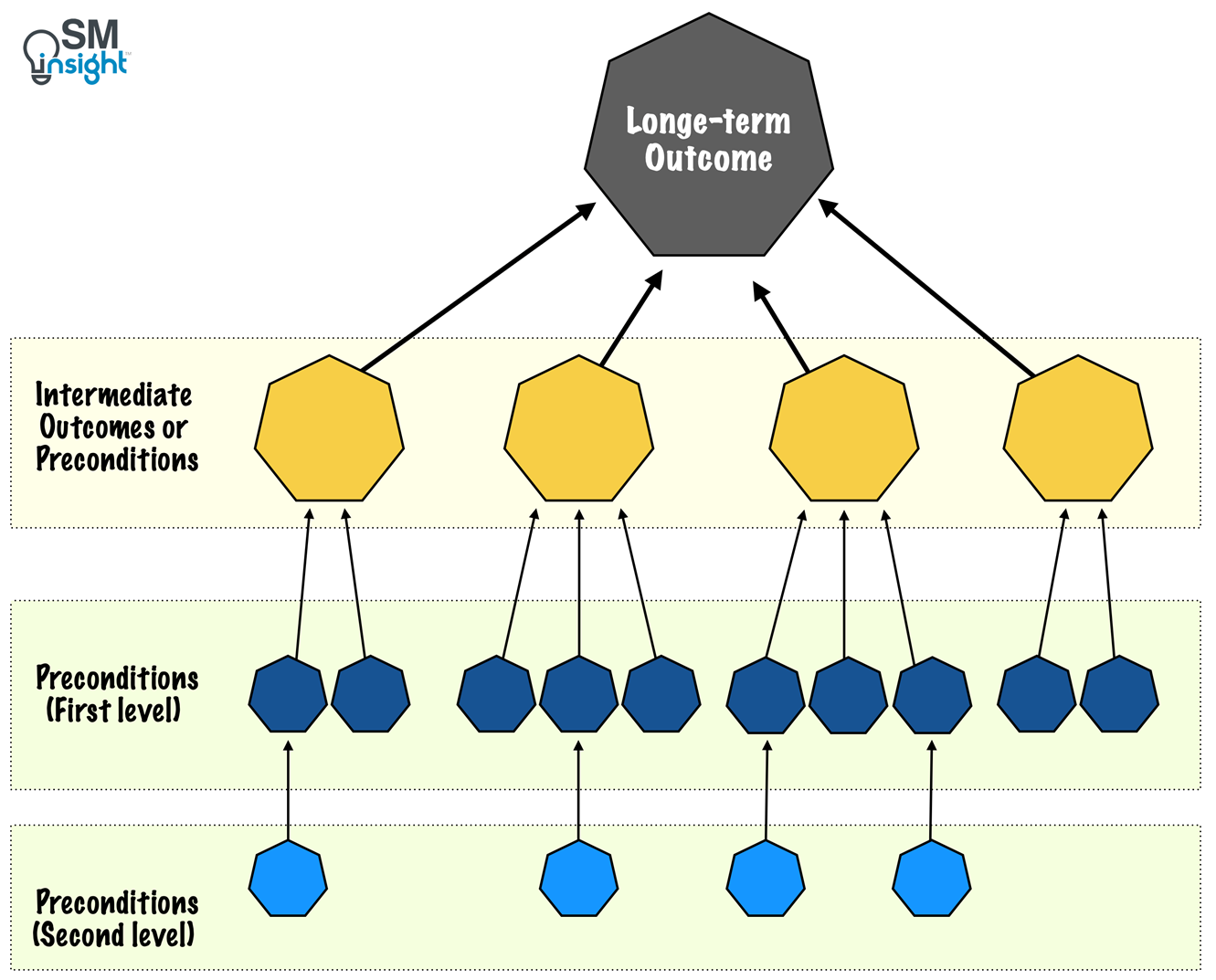

Brainstorming the first row of the pathway map

Participants can start by defining four to six most important preconditions for reaching the long-term goal.

As the mapping process moves, it is important to focus on preconditions that represent the most immediate outcomes related to the ultimate goal. Preconditions that occur very early in the change process don’t belong to the first row.

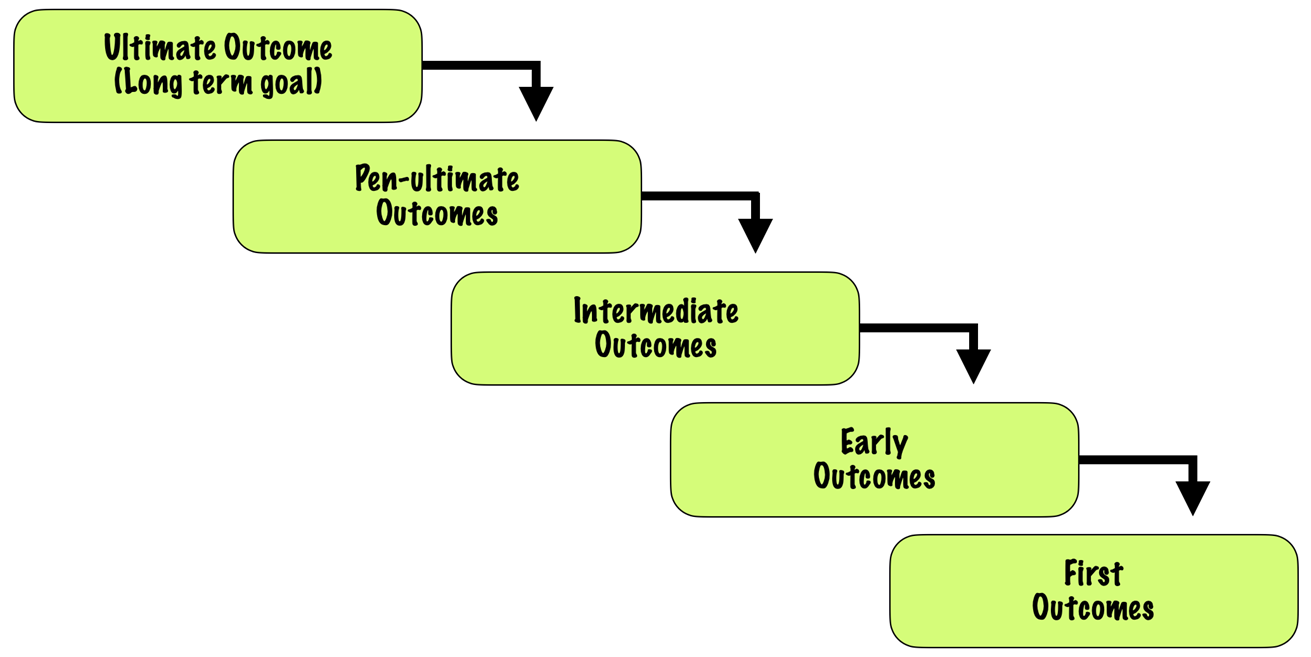

The key idea is to move from the last change that needs to happen before reaching the goal to the penultimate (next-to-last), to the early outcomes, and finally to the first outcome on the PoC.

Sorting and narrowing down the list

In this step, ideas about preconditions are sorted and similar ideas are grouped together.

The idea pool is narrowed down to four to six ideas that reflect the group’s best thinking about the necessary and sufficient “last outcomes” necessary to realize the long-term outcome. The first level PoC is then constructed on a clean sheet of poster paper.

Backwards mapping

For each precondition, more backward steps are taken to answer the question about preconditions (stated earlier). The process continues down each pathway (typically for at least three steps, but not more than five) until the group has filled in enough outcomes to reach the first row of the map.

At each step, the group stops to process its thinking, narrow down the pool of ideas, and note the choices in the appropriate place on the map.

The result of backward mapping is a storyline that makes sense as a way to depict how the change process will unfold.

3. Operationalizing preconditions

The term “operationalizing” means that for each precondition in the PoC, participants need to answer the question: “What evidence will we use to show that this has been achieved?”

The answer to this becomes the indicator that helps track progress and document success. Tackling this task early on helps to know exactly what targets to shoot for before planning interventions (next step).

It is crucial that participants think about the best indicator first before turning to the task of figuring out how to measure it.

Participants also tend to limit their thinking by bringing up only ideas related to the data they have access to, and consequently limit the power of this step by mismatching outcomes to indicators.

For example, test scores may be taken as a good indicator of youth advancement in a program, not because the program was designed to improve test scores but because they are easily available. Hence, it is important that the team avoids force-fitting indicators by limiting their imagination to the data they know they already have.

The process of operationalization of outcomes (which, too, are preconditions) happens one at a time until each of them has been considered. For each precondition, the group will need to determine the following:

- Indicator: what parameter will be used to measure the success of the precondition?

For example, a group working on school readiness may identify “All children are healthy at age five” as a precondition to school readiness in their PoC. A good indicator of child health might then be the percentage of kids who have a healthy height/weight ratio or the average number of days out of school due to illness. - Target population: who or what is expected to change? e.g.: Parents? Children? Teachers? Schools?

- Baseline: the current status of the target population on the indicator. This will be used to define what a successful change looks like.

- Threshold: how much does the target population need to change? This is the point that needs to be crossed in order to proclaim the success of the outcome.

- Timeline: How long will it take for the target population to reach the threshold of change on the indicator? This will have implications for how soon the long-term outcome can be reached.

Steps to operationalize preconditions

To operationalize preconditions, first, a clean, uncluttered version of the PoC is posted for everyone’s reference. In addition, copies on smaller paper are also distributed as handouts for participants. Next, the definitions of the key terms are explained to each participant.

With everyone on the same page, each of the preconditions is assigned to a participant (often, more than one to each). The facilitator then asks participants to answer the following questions:

- What indicator(s) will be used to measure the success of this outcome?

- Who or what is expected to change?

- What is the current status of the target population on the indicator(s)?

- How much does the target population have to change to successfully reach the indicator(s)?

- How long will it take the target population to reach the threshold of change on the indicator(s)?

Participants must avoid “baseline questions” which are more detailed and specific aspects of the research process that will be addressed once the measurement instruments and methods to use are determined.

They must instead focus on creating a general framework or blueprint that the researcher or evaluator can use as a foundation for planning how to document progress on various preconditions.

4. Defining interventions

Interventions are high-level strategies for attaining long-term goals. Defining them involves planning program activities, policies, and actions necessary to achieve the ToC map’s outcomes.

It is important to discourage the natural tendency to think that a single “mega-program” at the early stage of the pathway will cause all the preconditions along the pathway to occur.

A good place to start is by distinguishing between the outcomes that are under the group’s control and those that are beyond the reach.

Deciding outcomes

The first step in defining interventions is to decide which subset of outcomes the group can attempt to address. This requires a group discussion along with a reality check.

The process also requires “expectation management” as the group may not have the capacity to act on all the preconditions on the map. By the end of this process, the group must emerge with a subset of outcomes to use as the basis for planning actions, programs, and policy changes.

Mapping action for the outcomes in the pathway of change

This step requires creative thinking and can be best approached by breaking tasks into small sub-group or individual assignments.

Once all the interventions have been mapped, each sub-group can explain its rationale for expecting the intervention to bring about the targeted outcome at the levels identified by the indicators that were chosen earlier.

This process must continue until each outcome on the map has been:

- Ruled to be outside of the influence of the initiative.

- Ruled to be the result of a domino effect that starts earlier in the change process.

- Matched to an intervention that can plausibly be expected to produce desired results.

The following questions can help guide the process:

- For each of the outcomes on the map that may have some influence, what type of intervention needs to be implemented in order to bring it about?

To answer this question, the group must avoid going into tactical thinking and instead focus on a general description of the type of strategy or type of program with just enough detail to allow the group to determine if it is plausible. - Will any specific programs/interventions that are currently offered bring about an outcome on this map?

This helps identify gaps in the existing programs. Mapping each element of an existing program to the range of outcomes in the pathway allows one to see where new activities need to be created or implemented. - Will policy changes or institutional practices be required to bring about this outcome? If so, what type of change is required?

For interventions that call for system change, this question helps specify the exact type of public policy or institutional practice that needs to change in order to bring about the required outcome.

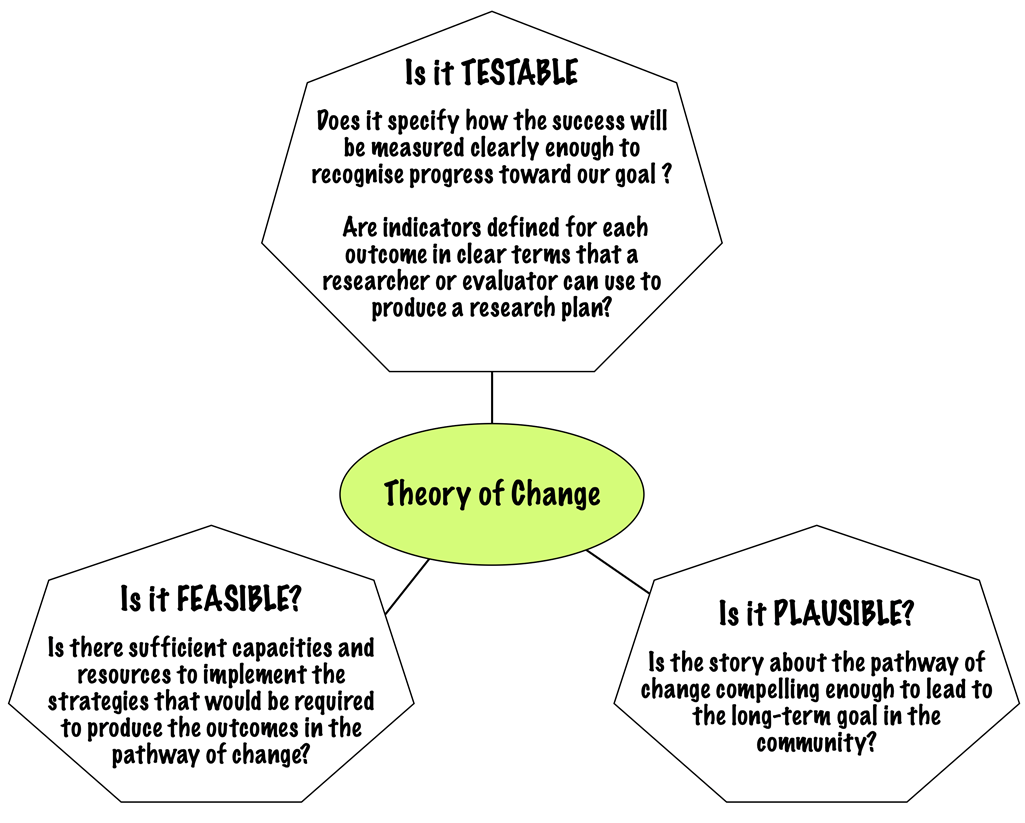

5. Articulating assumptions

Every change process is based on some shared assumptions that are taken for granted. The assumptions underlying a ToC are mainly of two types:

- The ones about why each precondition is necessary to achieve the result in the PoC and why the set of preconditions is sufficient to bring about the long-term outcome.

- The ones that come from social science theory which connects program activities to specific outcomes for specific populations or communities.

For example, findings from “best practice” research or evidence from academic (or basic) research.

It is important to articulate such assumptions so that they are examined, critiqued, and agreed on by the group.

In addition, there is a third type of assumption about the context/environment in which the ToC is situated which is also important to consider.

For example, a ToC developed to explain how a job training program will produce full employment in the neighborhood may be based on assumptions about the local economy, race, relations between potential employers and potential employees, and transportation access.

It is important to think critically about assumptions as should any one of them prove inaccurate, even the most elaborate PoC can fall apart.

The process for articulating assumptions

Articulating assumptions is like a review session that should ideally start by walking through the work done thus far.

This brings everyone on the same page about the storyline told by the PoC, the indicators that will be used to track success, and the intervention strategies that will be put in place to produce targeted outcomes.

The review is followed by a structured discussion that takes the group through the theory in a systematic way. The following questions help improve the quality of the responses:

- Does the theory make sense when looking at the total picture?

- Do the preconditions look like logical steps toward the long-term outcome?

- How will the outcomes be brought to the levels predicted?

- Is there anything in reality that can make it difficult to get the theory off the ground the way it is planned?

Such a discussion is bound to raise a lot of questions that the group must answer before the final approval. While seemingly frustrating, this step is crucial for checking the underlying logic of theory against the standards of quality.

The importance of questioning assumptions

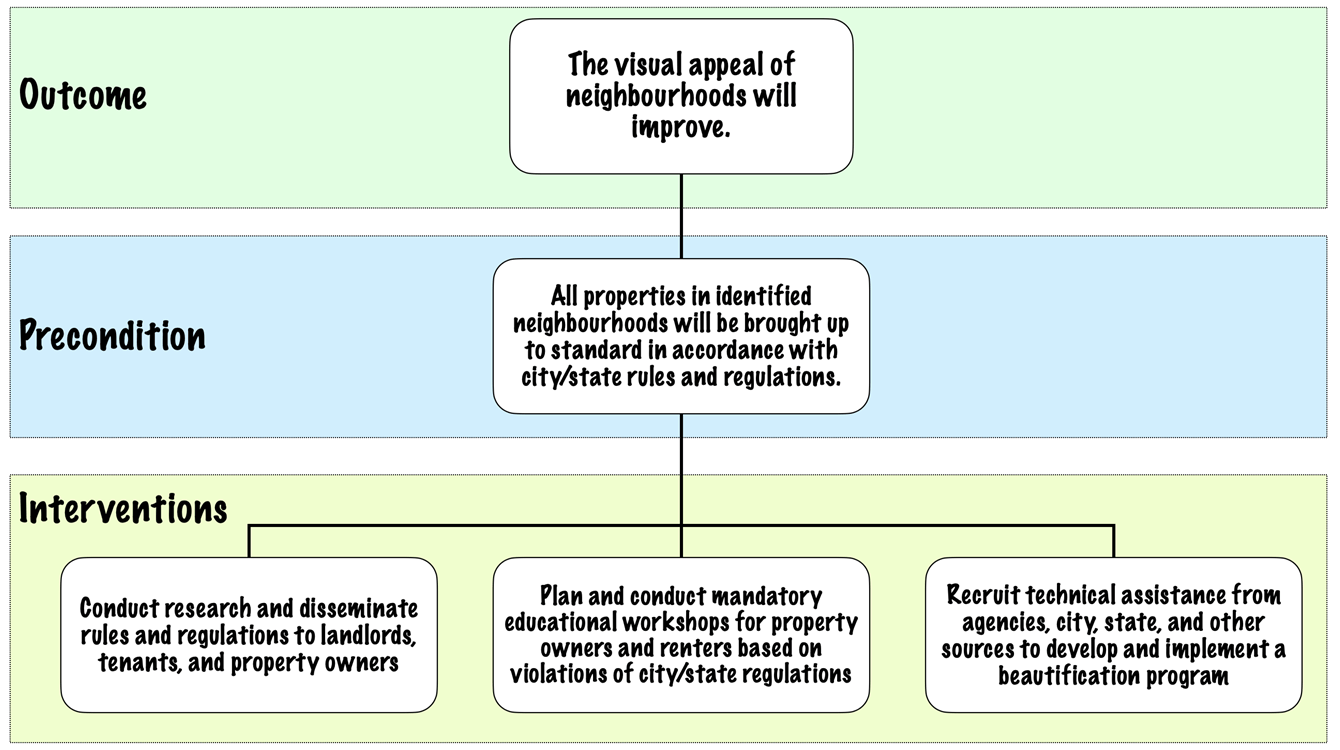

Consider the following ToC example drawn from a comprehensive community revitalization plan which illustrates the importance of probing assumptions:[2]

An implied assumption in the above case is that owners are simply unaware of the regulations and that by sharing the regulations with them, they will change their behavior.

But is this reasonable?

It is possible that the landlords are already aware of regulations and what may be needed is a threat of a fine to ensure adherence.

Another assumption in question is that the homeowners can afford to fix the violations and that once they’re made aware of them, they’ll act accordingly. If this assumption proves false, then the project is unlikely to reach its long-term outcome.

Putting it together

The main benefit of ToC comes from making different views and assumptions about the change process explicit. A good ToC specifies how to create a range of conditions that help a program deliver the desired outcomes.

It helps people set up the right kinds of partnerships, forums, technical assistance, tools, and processes to operate more collaboratively while being results-focused.

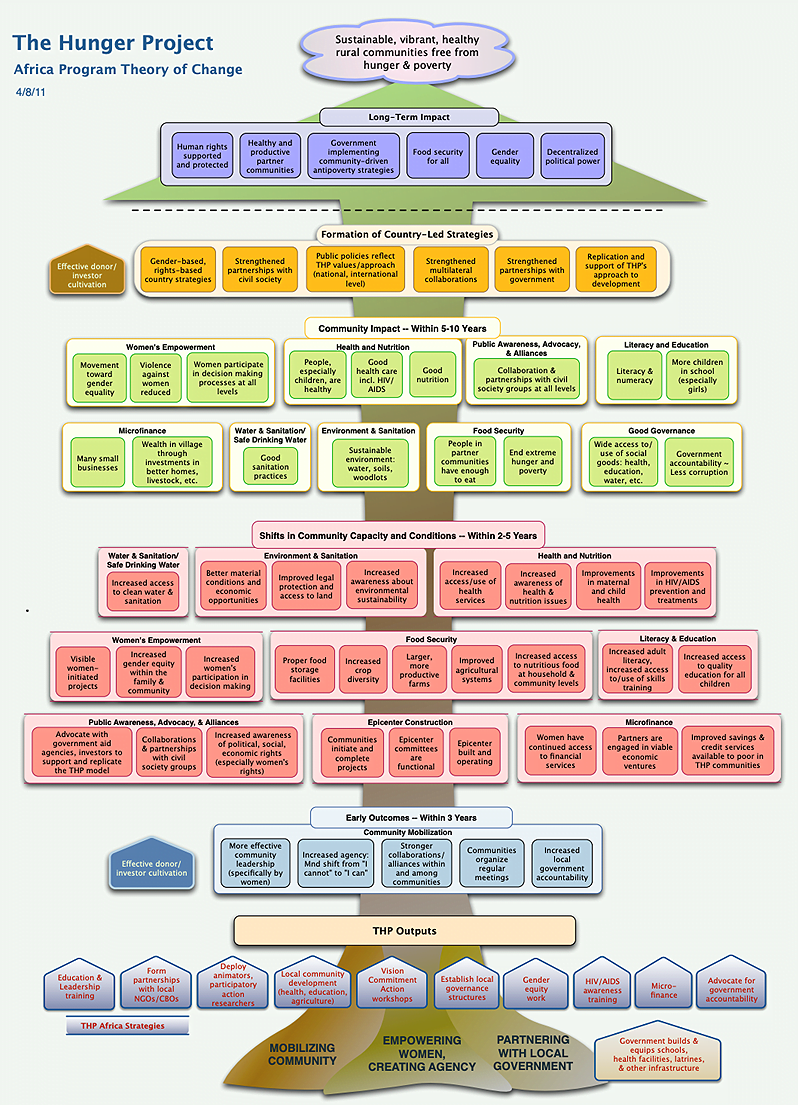

The example below shows a well-constructed ToC for a large social change initiative whose long-term impact is to achieve a sustainable rural community free of hunger and poverty.

Notice how the ToC visually connects the various complex elements at play to achieve the overarching objective:

Common reflags in ToC development

Below are some of the common red flags that, if present, undermine the success of a ToC initiative:

- Lack of mandate or buy-in from key decision-maker(s).

- Lack of participation by the right stakeholders.

- Outcomes are stated as actions or interventions and not conditions.

- Outcomes are compound statements.

- Outcomes are too vague for decision-making.

- Outcomes are not chronological.

- Not enough time and follow through given to the process – backwards mapping doesn’t always work right away.

- Facilitation is not set up and run properly.

Limitations of ToC

While developing ToC holds numerous benefits, it is also helpful to understand its potential limitations and ways to address some of the common ones:

ToC’s visual depictions can make the change pathways appear predictable

While ToC helps collaborators surface important questions and regularly measure their work to learn about progress, its depictions must not be viewed as firm, predictive models for how change will happen.

New obstacles can always surface in reality; hence collaborators must be mindful of assumptions and influencing factors.

For example, it can be difficult to predict relationships between different actors or parts of a system or to foresee external events or other emerging factors.

Graphic depictions often show change as a straight line, but in reality, it is seldom linear

Progress can show up in different ways in complex social change efforts. Sometimes, a step forward might be followed by two steps back as some setbacks are common.

For example, protection against or even mitigation of a known threat may constitute important progress. It is difficult to portray such nuances graphically, but groups can use the ToC process to surface expectations about the different forms that positive outcomes could take.

The ToC development process can lead to fatigue or frustration for some

Developing ToC is a complex and time-consuming task, especially if collaborators are committed to an inclusive process or need to work through fuzzy or divergent thinking.

This can feel frustrating, especially to those who see ToC development as “thinking, not doing” or otherwise not valuable or necessary.

Frustrations might turn into pressure to take shortcuts in the process that undermines its effectiveness. Ensuring that all parties are aware of the benefits can help, as can carefully considering how to structure the process to be as efficient and productive as possible.

Sources

- “THEORY OF CHANGE UNDAF COMPANION GUIDANCE”. United Nations Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF), https://unsdg.un.org/resources/theory-change-undaf-companion-guidance. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

- “Using ‘Theories of Change’ in international development”. INDEPENDENT EVALUATION GROUP (World Bank), https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/blog/using-theories-change-international-development. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

- “Using Results Chains to Depict Theories of Change in USAID Biodiversity Programming”. United States Agency for International Development, https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00M8MW.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

- “Review of the use of ‘Theory of Change’ in international development”. UK Department of International Development, https://www.theoryofchange.org/pdf/DFID_ToC_Review_VogelV7.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

- “An Analysis of Theories of Change in USAID Solicitations for Education Programs in Crisis and Conflict Affected Environments”. USAID, https://www.edu-links.org/resources/analysis-theories-change-usaid-solicitations-education-programs-crisis-and-conflict. Accessed 15 Mar 2024

- “Why Your Theory of Change is Critical to Your Organization’s Impact”. Geneva Global, https://www.genevaglobal.com/blog/why-your-theory-of-change-is-critical-to-your-organizations-impact. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

- “Using a theory of change (ToC) to better understand your program”. Learning for sustainability, https://learningforsustainability.net/post/theory-of-change/. Accessed 15 Mar 2024

- “The Hunger Project – Africa Program Theory of Change”. The Center For Theory of Change, https://www.theoryofchange.org/wp-content/uploads/toco_library/pdf/HungerProject%20AfricaProgramTheoryofChange.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2024

Thank you very much for this comprehensive guide on ToC!

You are contributing a lot to this community.