Silicon Valley giants such as Google, Facebook, Netflix, LinkedIn, Airbnb, and X (Twitter) have had one thing in common – the way they set objectives and measure results.

Since their early days, these firms have used a goal-setting framework known as Objectives and Key Results or OKRs to ensure that employees focus on the right outcomes, align with the company’s overall goals, and commit to delivering those goals with accountability.

While OKRs’ broadest adoption has been in the tech industry, over the decades, the tool has proven to be a Swiss Army knife – suited to almost any industry. Companies as diverse as Anheuser-Busch, BMW, Disney, Exxon, and Samsung including non-profit organisations like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation have benefited by adopting OKR [1].

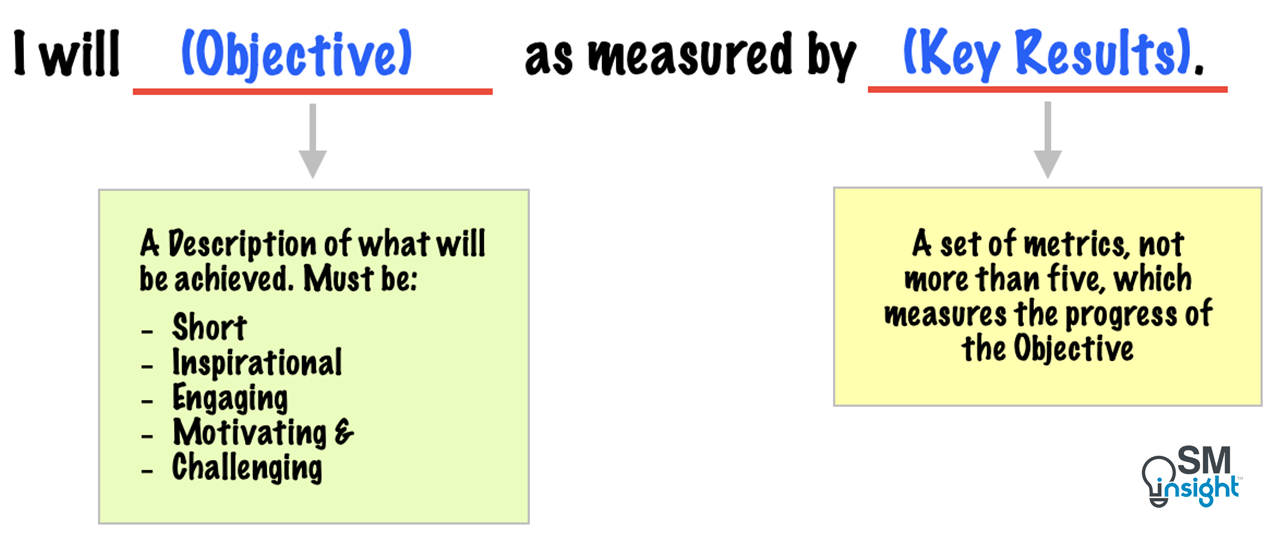

As the name implies, OKR has two components – the Objective and Key Results. It subjects any given goal to dual scrutiny – “What will be achieved?” and “How will it be measured?”.

When adopted with the right mindset, OKRs drive clarity, accountability, and the uninhibited pursuit of greatness. As Google has shown, OKR has the potential to change the course of an organization forever.

History of OKRs

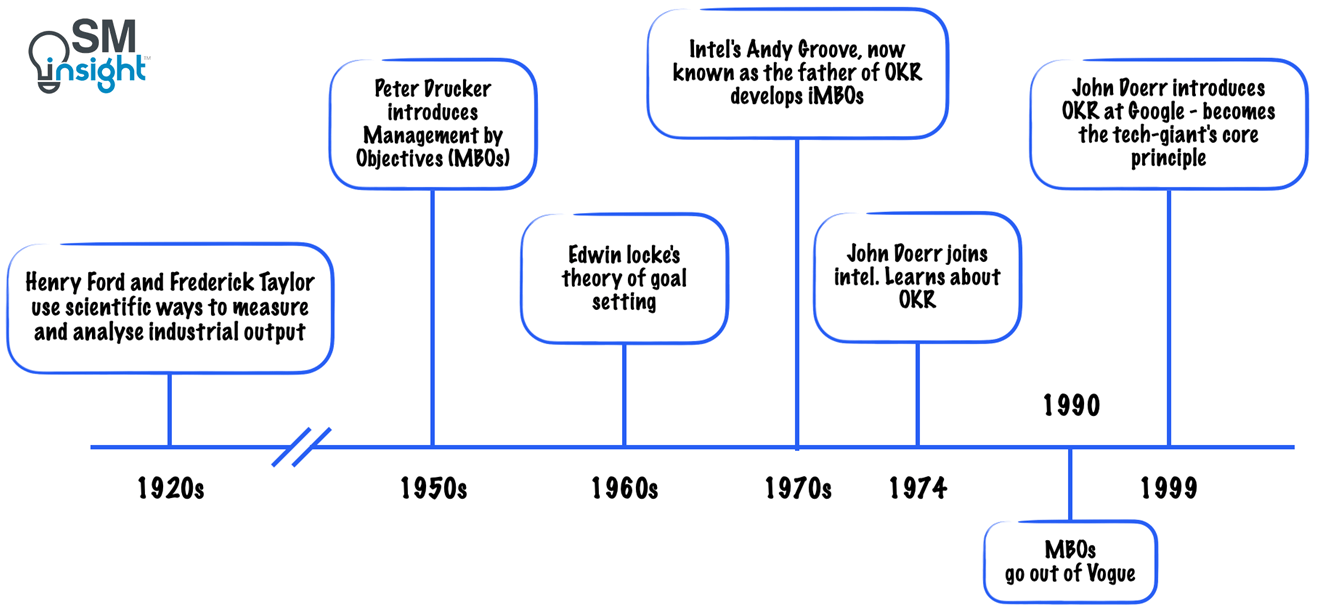

In management theory, the practice of systematically measuring output and analyzing how to get more of it was introduced in the early nineteenth century by Henry Ford and Frederick Winslow Taylor, who first applied these methods to improve industrial efficiency.

Half a century later, Peter Drucker introduced the idea of Management By Objectives (MBO) which put forth the idea that managers must have somewhere to go before they set out on a journey. This may seem obvious today, but in the 1950s, companies were run differently.

Drucker pointed out that managers often lost sight of their objectives and were caught in “the activity trap”, where they got so involved in their current activities that they forgot their original purpose. Worse still, some used day-to-day activities as a cover to avoid uncomfortable truths about their organization’s state.

Around the same time, Edwin Locke [4], an American psychologist introduced a theory that goal setting can motivate employees leading to better workplace performance. Organizations began to realize that having clear and measurable objectives directly contributed to the success and was a key component of corporate strategy.

By the late 1960s, MBOs were adopted by several forward-thinking companies like Hewlett-Packard with promising results. A meta-analysis of seventy studies showed that high commitment to MBOs led to productivity gains of 56%, versus 6% where commitment was low [5].

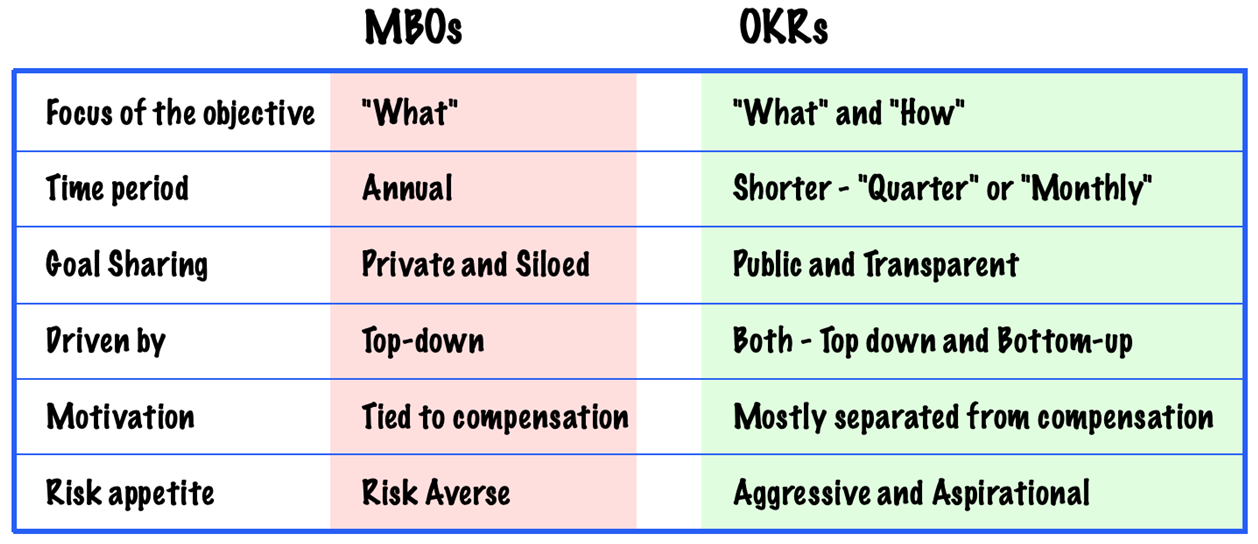

Eventually, though, the limitations of MBOs caught up as centrally planned goals were sluggish to trickle down the organizational hierarchy. Some became stagnant for lack of frequent updating; were trapped in silos; or were reduced to key performance indicators (KPIs) – numbers without sole or context. The most significant negative, however, was that objectives were tied to salaries and bonuses which discouraged innovation and risk-taking.

In the early 1970s, Intel’s Andrew Grove developed a framework, then known as Intel Management by Objectives (iMBOs), the early version of OKR which differed from the classical MBO in significant ways:

Around the same time, John Doerr joined Intel when the company was transitioning from a memory to a microprocessor company. Grove and the management team needed a way to help employees focus on a set of priorities to make a successful transition. OKRs helped them communicate those priorities, maintain alignment, and make that switch.

As an early investor in Google, Doerr introduced OKR to the budding tech startup in 1999. Since then, OKR has helped Google scale from a mere 60 employees to over 50,000 a decade later. The framework has been the backbone of Google’s signature home runs, including seven products with billion+ users – Search, Chrome, Android, Maps, YouTube, Google Play, and Gmail.

Cardinal features of OKR

The essence of a healthy OKR culture is ruthless intellectual honesty, a disregard for self-interest, and a deep allegiance to the team. It is based on the idea – “less is more” and uses a few extremely well-chosen objectives to impart a clear message about what people say ‘yes’ to and what they say ‘no’ to.

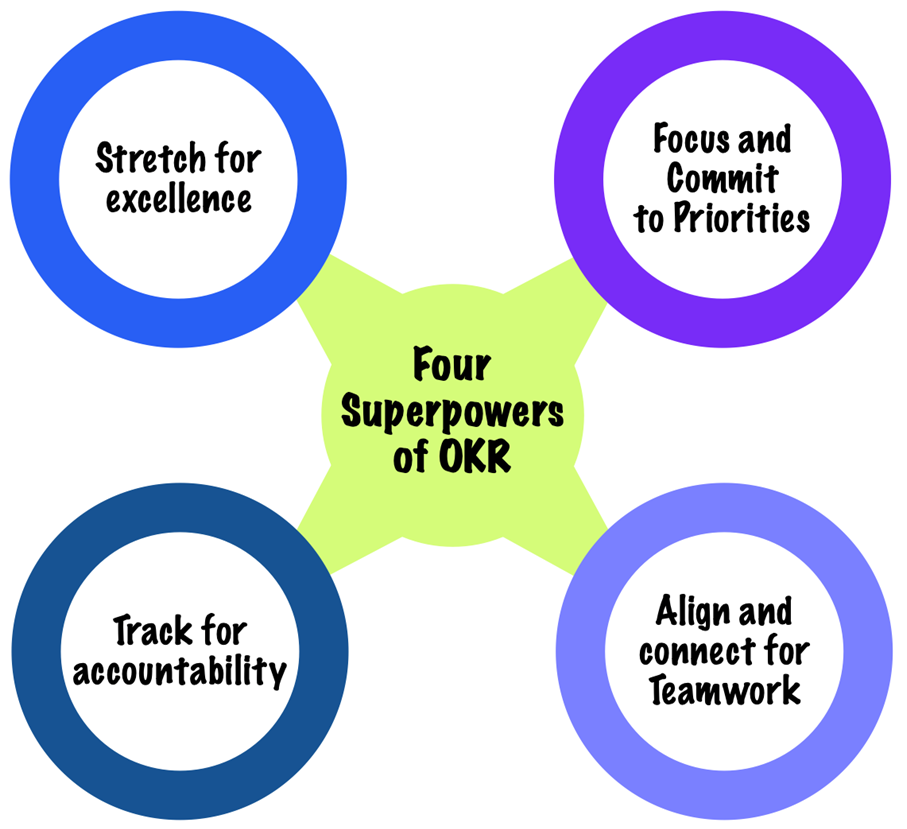

By limiting the number of objectives between three to five per cycle, OKR allows companies, teams, and individuals to choose what matters the most. OKR uses four cardinal features to turn good ideas into superior execution and workplace satisfaction. Each of them is discussed in more detail:

1. Focus and Commit to Priorities

To measure what matters, an organization must begin with the question: What is most important for the next three (or six, or twelve) months? As no one organization can “do it all,” the focus should be on a handful of initiatives that can make a real difference while deferring less urgent ones.

Focus and commitment must be driven by leadership

In the OKR framework, the process of goal-setting starts with disciplined thinking at the top – with leaders who invest the time and energy to choose what counts. Leaders start by asking: What are our main priorities for the coming period? Where should people concentrate their efforts? Once priorities are identified, leaders commit and stand firmly behind a few top-line OKRs which give teams a compass, and a baseline for assessment.

However, sometimes, powerful, and energizing OKRs can originate from frontline contributors. When it does, leaders must commit resources and focus the organization’s efforts on achieving the results.

For example, during the early days of YouTube, only a fraction of the people signed up on the platform due to poor login experience. Though it was the world’s third most visited site, its value remained hidden from hundreds of millions of people. The potential of converting visitors to members was first identified, at the frontline, by YouTube’s product manager Rick Klau.

Rick’s team devised a six-month OKR to improve the site’s login experience. They made their case to YouTube’s CEO, who consulted with Google’s CEO Larry Page. Larry agreed to elevate the login objective to a Google company-level OKR but with a deadline of three months instead of six. Once elevated, the objective took priority, and everyone rallied to help Rick’s group succeed. The update was completed on time [1].

Communicate the “why” and the “what”

Top-line goals must be clearly understood throughout the organization. It is important to communicate the “why” as well as the “what” of the goal as people need more than just milestones for motivation. Only when they see how goals relate to the mission, will they find it meaningful. Bringing this clarity into the organization is one of the significant challenges to the successful implementation of OKR.

Balance objectives and key results

Objectives and key results are the yin and yang of goal setting. While objectives are about inspiration and reaching far horizons, key results are earthbound and metric-driven. The latter typically include hard numbers for one or more gauges such as revenue, growth, active users, quality, safety etc.

To make reliable progress, it is important to be able to measure performance and results against the goal. A well-framed objective with three to five key results will usually be adequate to reach it while too many can dilute focus and obscure progress.

Set public goals with shorter timeframes

Most organizations follow a top-down process of goal-setting where the goals are only accessible to those concerned and the cycle is annual. OKR takes a different approach where goals are made public across the organization, the cycle is much shorter (quarterly, monthly, or even weekly), and the approach is highly collaborative.

While this can come as a shock to the established order, OKR’s short time frames intensify focus and commitment and make the organization nimbler than ever. Faster feedback leads to early corrections. While there is no protocol or no one-size-fits-all approach, the best OKR cadence is the one that fits the context and culture of the business.

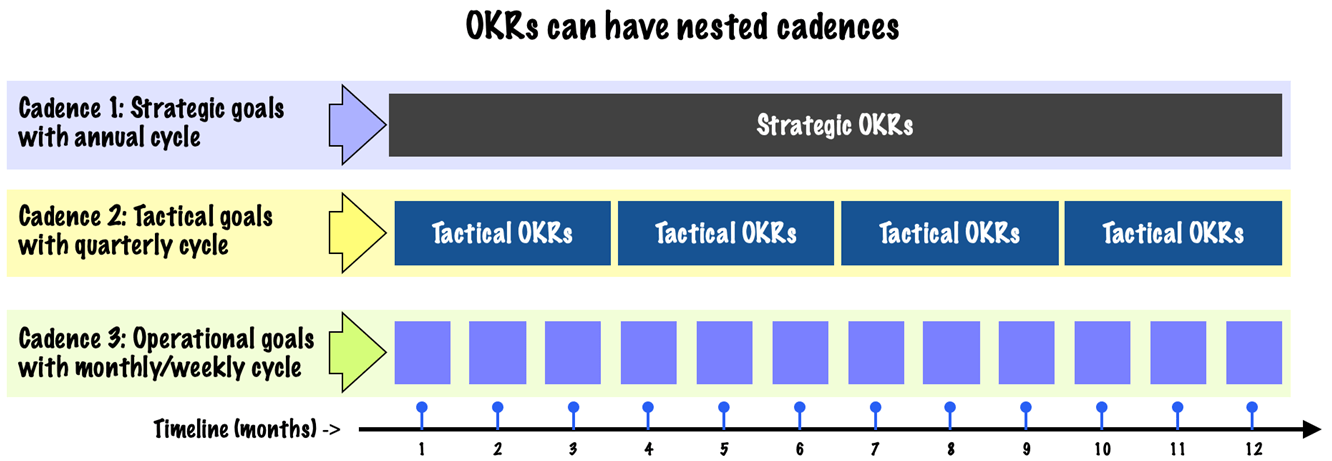

It is a common misconception that OKR only works with short-quarterly cycles. Using only short-term OKRs in every situation can cause teams to miss the big picture and focus only on what they can accomplish in the short term. As goals can have different rhythms, a mature approach to OKR is to have nested cadences that separate faster, tactical and operational goals from the strategic ones:

Balance the effects with counter-effects

When organizations focus on meeting specific, challenging goals, there is often a risk of achieving them at the cost of an undesired compromise elsewhere. This can prove costly.

For example, in 1971, after bleeding market share to fuel-efficient models from Japan and Germany, Ford countered with the Pinto, a budget-priced subcompact car. Pinto’s in-house green book cited three product objectives (key results):

- Truly subcompact (size, weight).

- Low cost of ownership (initial price, fuel consumption, reliability, serviceability).

- Product superiority (appearance, comfort, features, ride quality, handling, performance).

Unfortunately, safety was left out and with it, ethical behavior, and company reputation. Ford’s product managers skipped over safety checks in planning and development. Pinto’s gas tank was placed just six inches ahead of a flimsy rear bumper. Hundreds of people died after Pintos were rear-ended, and thousands more were severely injured. In 1978, Ford paid the price with a recall of 1.5 million cars [6].

Ambitious OKRs come with the risk of overlooking a vital criterion that might severely impact elsewhere. Hence, it is critical to measure and balance both – effect and counter-effect.

Chasing perfection is futile

Organizations sometimes obsess over defining the right OKRs while forgetting the fact that OKRs are inherently works in progress, not commandments cast in stone. Sometimes, it can take weeks or months for the right key results to emerge after a goal is put into place.

OKRs can be modified or even scrapped at any point in the cycle. However, the goals must be succinct, specific, and measurable while completion of their key results must result in the attainment of the objective.

Get used to the “less is more” approach

The ideal number of quarterly OKRs, in most cases, should range between three and five. While it may be tempting to take on more objectives, this can blur focus or lead to distraction. In the OKR system, the traditional approach of top-down mandates to “just do more” becomes obsolete. Orders give way to the question: What matters most?

Every commitment to a goal is made at the expense of a chance to commit to something else. Hence, OKR is about the art of selecting, from the many activities of seemingly comparable significance, the one, two or three that provide leverage well beyond the others and concentrating on them.

2. Align and Connect for Teamwork

Alignment is crucial. A McKinsey study has shown that when people understand and are excited about the direction their company is taking, the company’s earnings margin is twice as likely to be above the median [7].

Transparency drives alignment

When goals are made public, they are more likely to be attained as public goals go through higher scrutiny leading to meaningful improvements in the rate of behavioral performance and goal attainment [8].

In an OKR system, every goal, from the most junior-most staff to the CEO, is open for everyone to see. Critiques and corrections are out in public view, and it is easy to spot where the best ideas are coming from. It also becomes apparent that the individuals moving up are the ones delivering what the company most values.

In such an environment, when an employee struggles to reach an objective, colleagues can easily spot that help is needed and offer support. Negative aspects such as suspicion, sandbagging, and politicking lose their toxic power in the OKR system.

By clearing a line of sight to everyone’s objectives, OKRs bring alignment, expose redundant efforts, and save time and money.

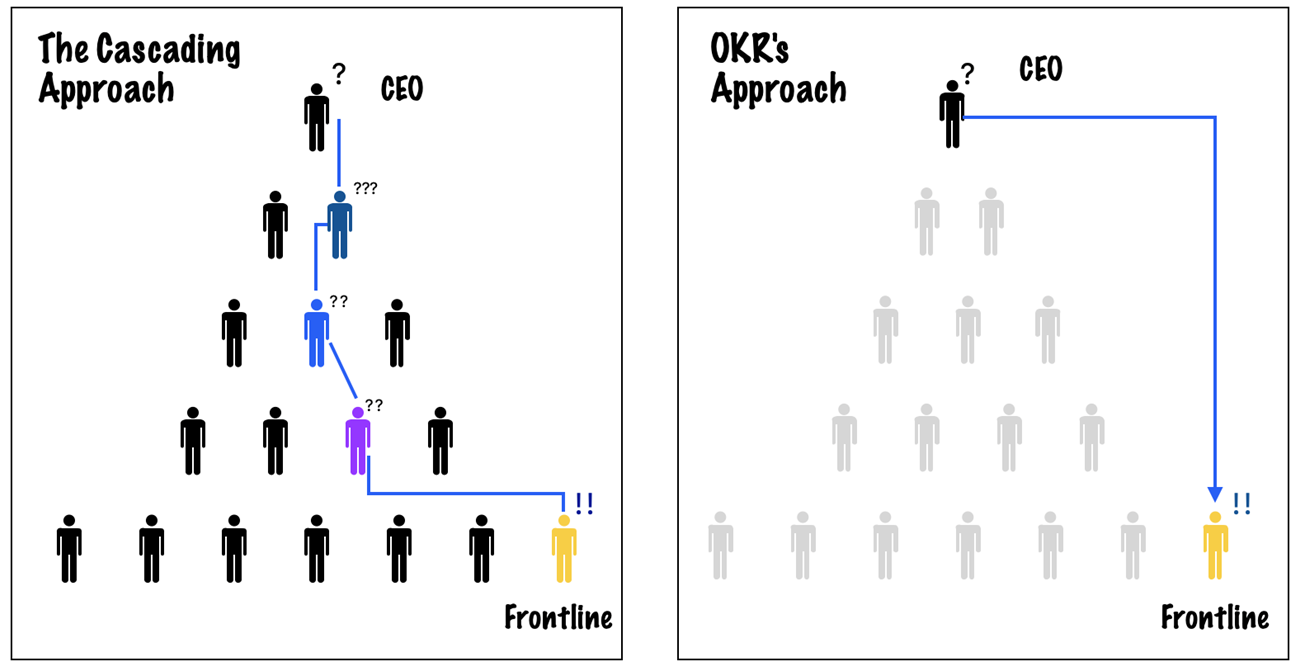

Cascading goals top-down is inefficient

Traditionally, work was strictly driven from the top and goals were handed down the org chart. This approach of cascading goals works by ringfencing lower-level employees and guaranteeing that they work on the company’s chief concerns. While no longer universal, this approach remains prevalent in larger organizations.

Cascading can make operations more coherent, but when all objectives are cascaded, the process leads to four adverse effects:

- Loss of agility: Even medium-sized companies can have six or seven reporting levels. As everyone waits for the goals to trickle down, and have review meetings, each goal cycle can take weeks or even months. Implementing quarterly OKRs may prove impractical in such scenarios.

- Lack of flexibility: since it takes a lot of effort to formulate cascaded goals, people are reluctant to revise them mid-cycle. Even minor updates can burden those downstream who scramble to keep their goals aligned. Over time, the system becomes burdensome to maintain.

- Marginalized contributors: Rigidly cascaded systems tend to shut out inputs from frontline employees – contributors will hesitate to share goal-related concerns or promising ideas.

- One-dimensional linkages: While cascading locks in vertical alignment, it’s less effective in connecting peers horizontally across departmental lines.

Because OKRs are transparent, they can be shared without cascading them in lockstep. For example, an objective might jump from the CEO straight to a manager, or from a director to an individual contributor. OKRs are set in a parallel process in which teams define OKRs that are linked to the organization’s objectives and validated by managers, in a process that is simultaneously bottom-up and top-down.

Balancing alignment with autonomy

Innovation tends to emerge on the edges of an organization – from people on the frontline who are in touch with and can sense impending changes early. Salespeople for example understand shifting customer demands before management does; financial analysts are the earliest to know when the fundamentals of a business change.

Micromanagement can lead to lost value. A healthy OKR environment must strike a balance between alignment and autonomy, common purpose, and creative latitude. It must provide contributors the freedom to set at least some of their objectives and most or all their key results. When people choose their destination, they will have a deeper awareness of what it takes to get there.

Google, for example, encourages its employees to set aside 20% of their time working on what they think will most benefit Google. Many of the company’s key products, such as Google News (2002), AdSense (2003), and Gmail (2004) started as an employee’s side project [9].

Encouraging cross-functional coordination

Because isolated individuals cannot match a connected group’s innovation and problem-solving abilities, connected companies are quicker companies. To grab a competitive advantage, both leaders and contributors need to link up horizontally, breaking through barriers.

A transparent OKR system enables this collaboration where people across the whole organization know what the goals are and can see what’s going on. This sends clear signals to everyone and kicks off virtuous cycles that reinforce everyone’s ability to get the work done.

3. Track for accountability

OKRs are not objectives cast in stone. They must be tracked, revised, and adapted as circumstances dictate. The life cycle of an OKR consists of three phases – The Setup, Tracking and Wrap-Up:

Setting up OKRs

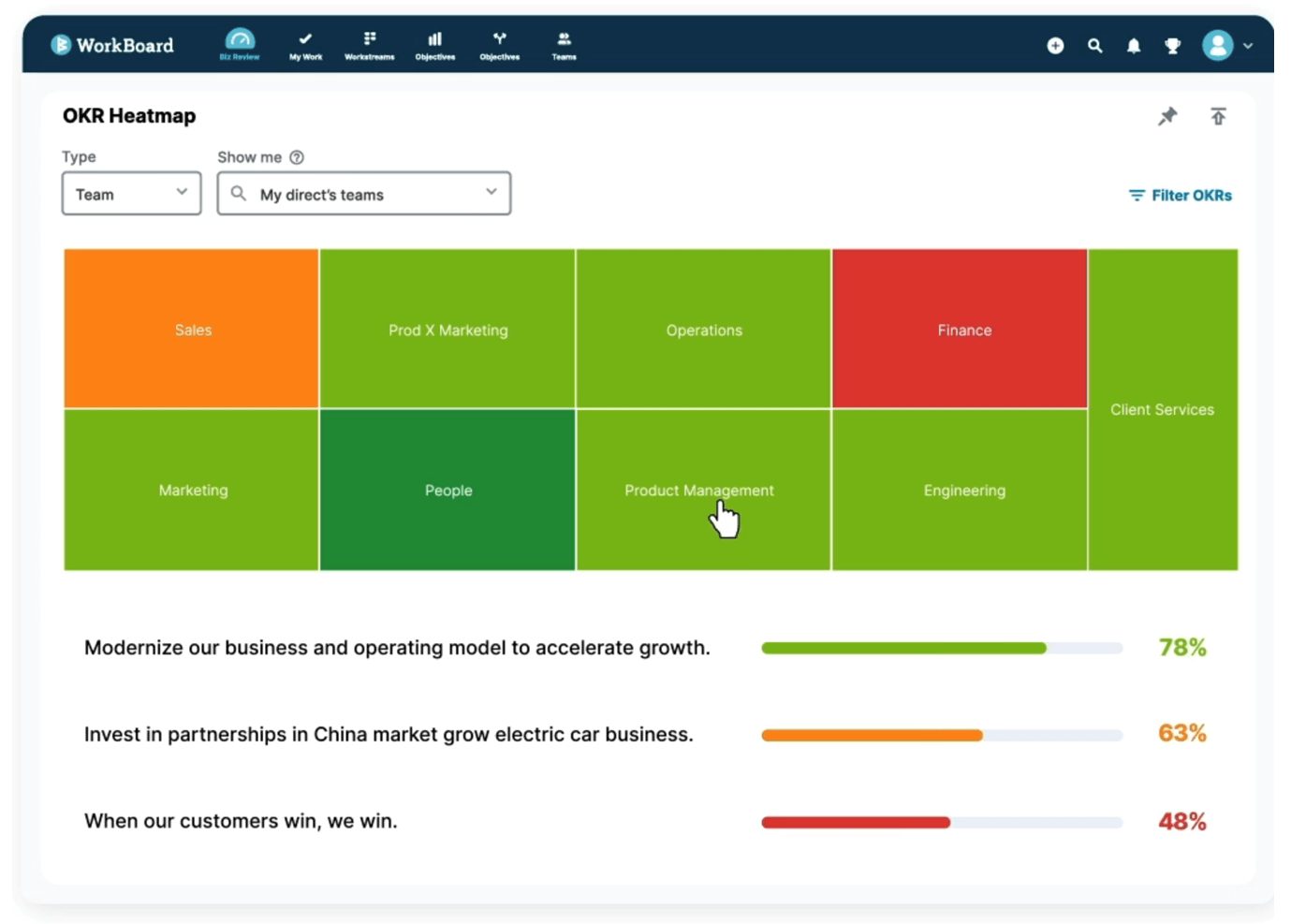

For OKRs to scale, dedicated software is a must

Tracking OKRs and their progress can be complex. While small organizations may still get away with general-purpose software like MS Word, such an approach wouldn’t scale in large organizations. For example, a company with 50,000 employees following a quarterly OKR process would have to track at least 200,000 OKR files annually.

A large number of OKRs, even though would be public, wouldn’t be truly transparent as no one would have the patience to search for connections or alignment. Hence, to effectively implement and track OKRs, organizations must use OKR management software. These software are designed to feature dynamic dashboards and automated tools to help manage and track progress:

By allowing contributors to see how their work contributes, they save hours that would otherwise be wasted digging for information in meeting notes, emails, documents, and slides. They make goals more visible and help drive engagement, promote internal networking, and save time, money, and frustration. They make sure relevant information is ready when needed.

Have an OKR shepherd

Universal adoption is crucial for an OKR system to function effectively. If exceptions are made, output will be suboptimal. But every organization will have some late adopters, resisters, and procrastinators. A best practice for addressing these hurdles is to designate one or more OKR shepherds – senior executives who can monitor, motivate and even enforce actions when necessary.

Tracking OKRs

Research has shown that making measured headway can motivate people more than public recognition, monetary incentives or even achieving the goal itself [11]. While OKRs do not require daily tracking, regular check-ins, preferably weekly, are essential to prevent slippage. Fortunately, OKR software comes with visual aids to show progress.

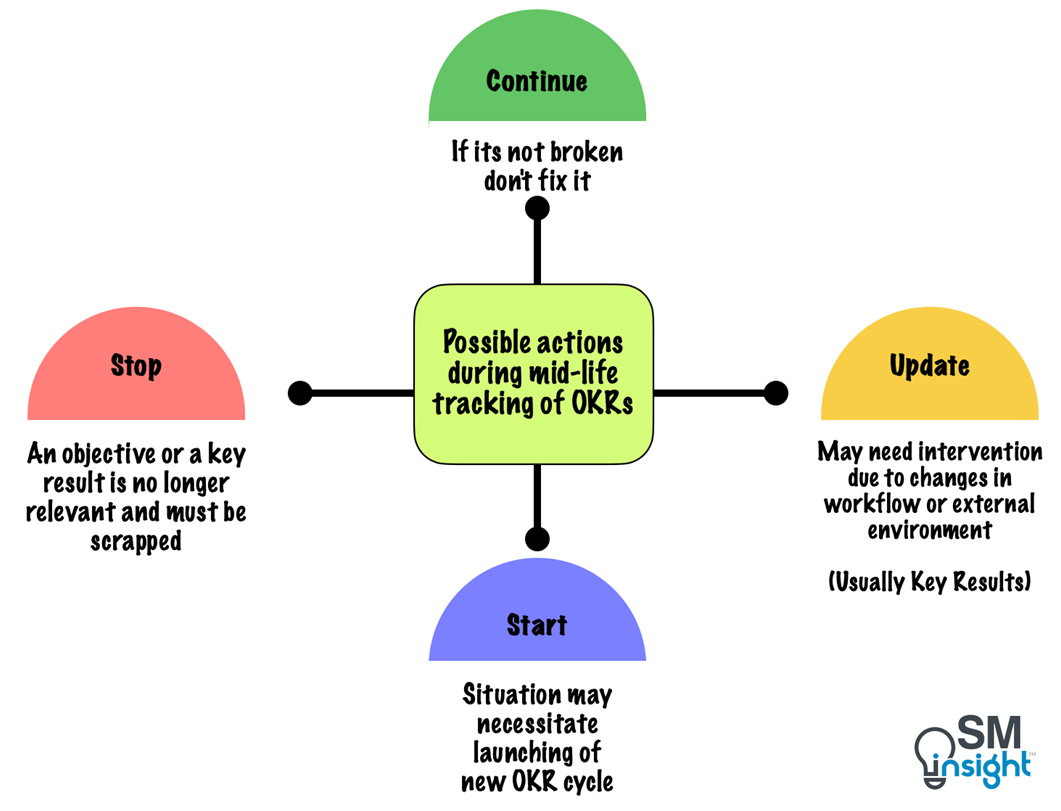

Adaptable by nature, OKRs are meant to be guardrails. When tracking OKRs, at any point in the cycle, there are four options:

- Continue: This is the green zone where a goal is on track and doesn’t require an intervention. The best course is to continue doing what works.

- Update: This is a yellow zone where a key result or an objective needs an intervention to respond to changes in the workflow or external environment. Executives must address questions such as: what could be done differently to get the goal on track? Does it need a revised timeline? Should other initiatives take a backseat to free up resources for this one?

- Start: Some situations can necessitate the launch of a new OKR mid-cycle. For example, a sudden industry disruption may require a tech company to embrace an emerging technology that is very different from what it started with.

- Stop: This is a red zone where a current objective or a key result has outlived its usefulness and is now at risk of being irrelevant. Key results are more likely to fall in this zone compared to well-thought-out objectives. The best solution is to drop them.

For best results, OKRs must be scrutinized several times per quarter by contributors and their managers. Progress must be reported, obstacles identified, and key results refined.

Wrapping-up OKRs

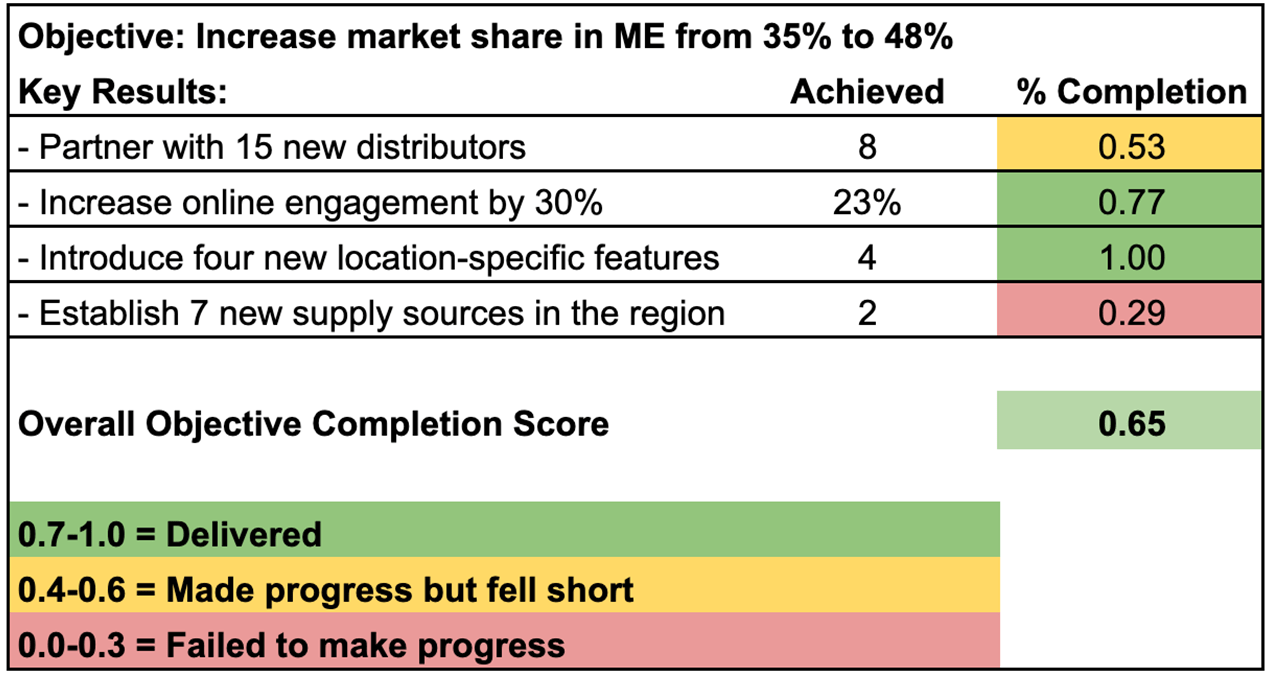

Post hoc evaluation and analysis of OKRs can reveal tremendous insights hence when the work cycle is complete, each OKR must be scored, self-assessed and reflected upon:

Scoring

An honest objective assessment of OKRs reveals what’s achieved, provides crucial inputs to address difficulties faced, and reveals insights on how to do it better next time. Most OKR software pack the ability to generate scores automatically, where the numbers are objective and untouched by human hands.

When performing manual scoring, however, the simplest and cleanest way is to average the percentage completion rates of associated key results to arrive at the overall objective level score. Score-based color codes can then be assigned for a quick overview of the status:

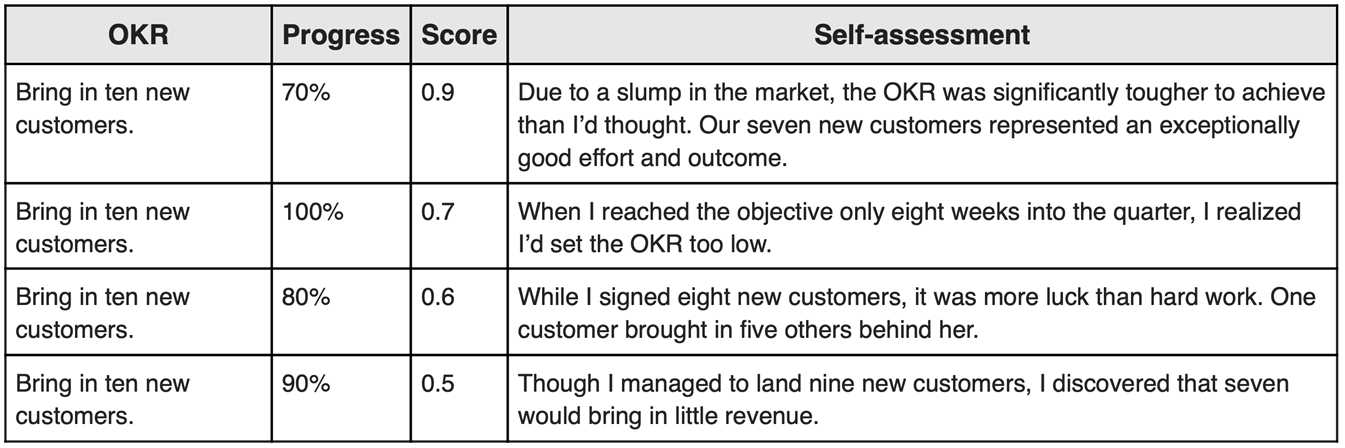

Self-Assessment

In evaluating OKRs, combining objective data obtained from scoring with the goal setter’s thoughtful, subjective judgment can bring new insights. It is always possible that numbers might hide a strong effort or strong numbers could have little to do with efforts.

For example, at Google, when employees perform self-assessment, it is not about whether they got a red, yellow, or green, but a list of what they’d delivered that was above business as usual and connected to the company’s goal. Googlers are encouraged to use their OKRs in self-assessments as guides, not as grades.

While some will grade themselves too harshly, others may need to be challenged. In either case, an alert facilitator or team leader must recalibrate the assessment. In the end, learnings matter more than numbers.

Reflection

OKRs are inherently action-oriented and work in a cycle of aggressive goal-setting and a battle to achieve most of them. It is equally important to pause to reflect on the achievement and then repeat the cycle.

Some of the questions to ask before closing an OKR cycle include:

- Were all the objectives accomplished?

- If yes, what contributed to the success?

- If not, what obstacles were encountered?

- If the same goal were to be achieved again, what would one change?

- What are some of the learnings that may alter the approach to the next OKR cycle?

OKR wrap-ups are retrospective and forward-looking at the same time. Appraising the work done and owning up to any shortfalls is important.

4. Stretch of excellence

Set stretch goals

The value in setting stretch goals was identified by Edwin Locke and Gary Latham, who concluded that although subjects with very hard goals reached there far less often, they consistently performed at a higher level and were not only more productive but also more motivated and engaged [12].

Setting ambitious goals is so central to OKRs that Google mentions it among the “Ten things we know to be true” – 10 basic concepts that form the core of the company’s philosophy [13]. For companies seeking to prosper, stretching is not optional.

In the OKR process, goals must belong on the border between abilities and dreams – they must unearth fresh capacity, hatch creative solutions, and revolutionize business models. They are the kinds of goals that:

- Takes people out of their comfort zones.

- Makes them go after targets that they think they can’t reach (at least not yet).

- Makes teams wonder how far they can go.

- Encourage teams to rethink the way they work, ask hard questions and have difficult conversations.

- Makes teams achieve things that they didn’t do before.

- Are hard, but not so much that they demotivate people.

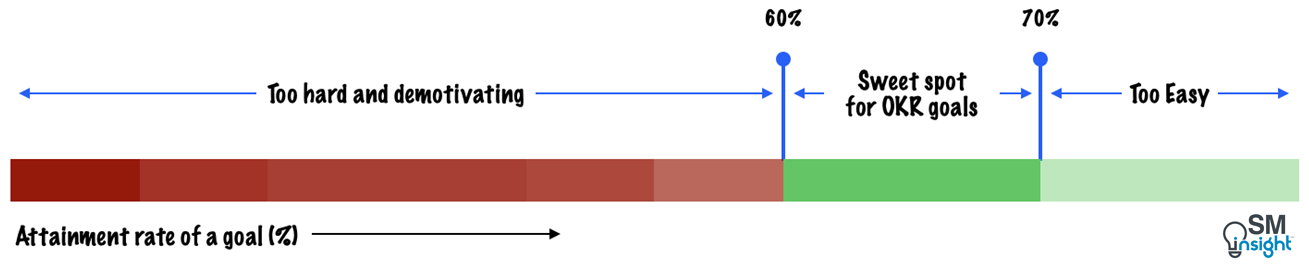

The sweet spot for a stretch goal

To succeed, a stretch goal must not seem like a long march to nowhere. Nor can it be imposed without regard to realities on the ground. The ideal sweet spot for a goal’s likelihood of attainability must be between 60% to 70%. If goals are consistently achieved 100% of the time, it implies they aren’t ambitious enough.

Have two goal baskets – committed and aspirational

Organizations can have a varied range of risk tolerance which may change over time. The greater the margin for error, the more a company can extend itself. However, in business, it is imperative to attain certain goals, such as sales and revenue targets, while flexibility may be afforded in others.

One way to address this is to divide OKRs into two categories; committed goals (Roofshots) and aspirational goals (Moonshots):

| Roofshots (Committed Goals) | Moonshots (Aspirational Goals) |

|---|---|

| Well-defined metrics concerning business targets such as product release, hiring or sales | More strategic – reflect the bigger picture, high-risk and future-tilting ideas |

| Set by management at company level and employees at department level | Can originate at any level. They aim to mobilize the entire organization |

| Goals that are hard but achievable | Stretch goals that are just beyond the threshold of what seems possible |

| Achieving 100% means success | Challenging to achieve with a high chance of failure. Success means achieving 60-70% |

The relative weightage of the two baskets depends on the organization’s culture, aspirations, risk-taking ability, and financial resources at its disposal. However, in pursuing high-effort, high-risk goals, employee commitment is crucial. Leaders must convey two things: the importance of the outcome, and the belief that it’s attainable.

Delivering high performance with OKRs – the CFR approach

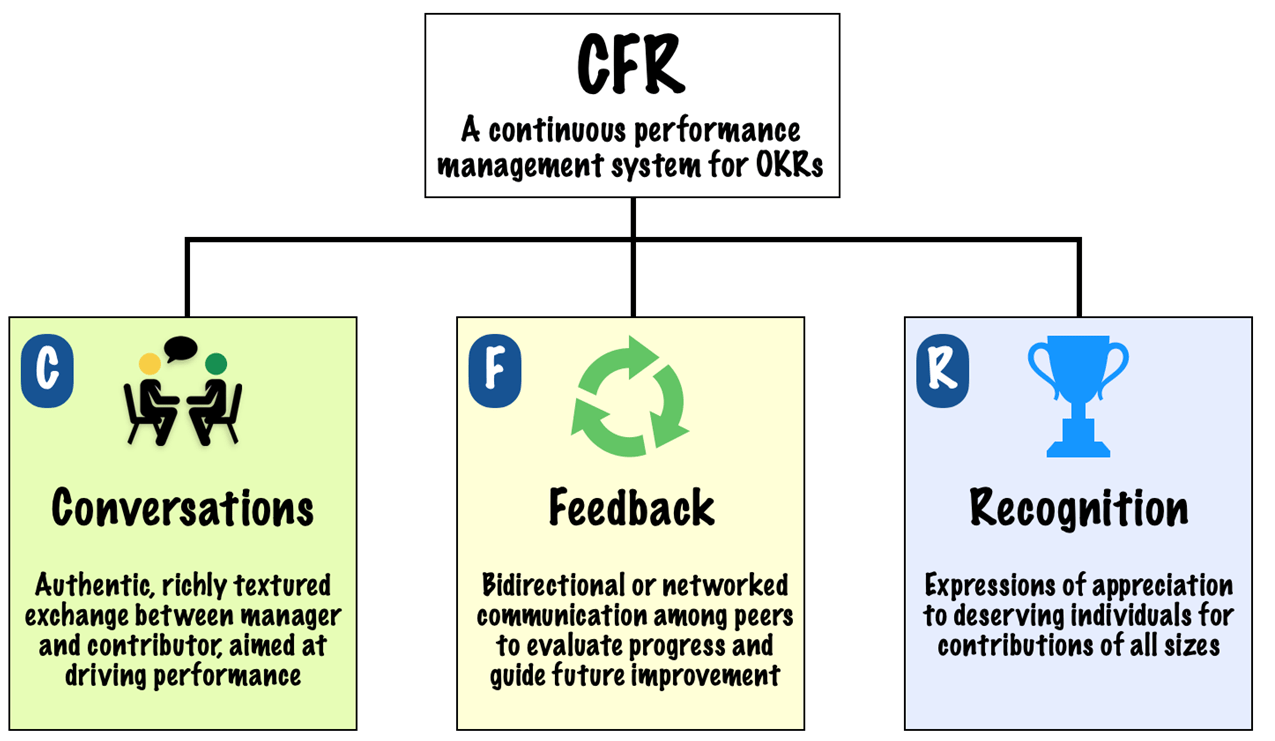

OKRs are better managed with a continuous performance management approach that uses an instrument known as CFR (Conversations, Feedback & Recognition):

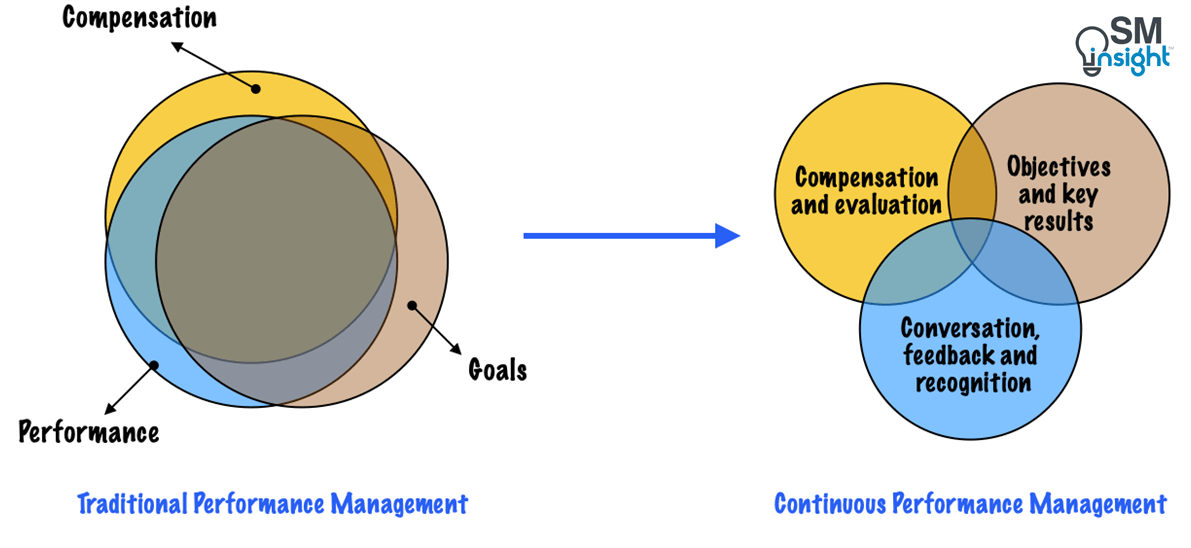

The CFR’s approach is different from the traditional performance management systems (PMSs) in several important ways:

Feedback is continuous

Conventional PMSs with annual review cycles are incompatible with the fast-paced, ambitious nature of OKRs. They emphasize holding employees accountable for what they did last year at the expense of improving performance now and in the future.

Using CFR, companies replace the annual review with ongoing conversations and real-time feedback. Improvements are made throughout the year while alignment and transparency become everyday imperatives. Unsurprisingly, traditional PMSs have been abandoned by more than a third of U.S. companies as per a 2016 Harvard report [14].

Compensation is decoupled from OKRs

OKR is a management tool, not an employee evaluation tool. Hence it is important to separate OKRs from compensation and promotions. Research has shown that when goals are used to set compensation, employees become defensive and stop stretching for amazing results. They get bored for lack of challenge and the organization suffers most.

At Google, for example, OKRs amount to only a third or less of performance ratings. They take a backseat to feedback from cross-functional teams and, most of all, to context [15].

A shift from directing to coaching

Conversation (C in CFR) is about promoting one-on-one meetings between the manager and direct report where the former teaches skills and know-how and suggests ways to approach things. These are meetings where the subordinate sets the agenda and tone while the supervisor is there to learn and coach.

Effective one-on-ones dig beneath the surface of day-to-day work and help address five critical areas of conversation between manager and contributor:

- Goal setting and reflection: Employee’s OKR plans are set for the coming cycle. The discussion focuses on how best to align individual objectives and key results with organizational priorities.

- Ongoing progress updates: brief, data-driven check-ins on the employee’s real-time progress, with problem-solving as needed. (What’s working well? What’s not?)

- Two-way coaching: to help contributors reach their potential and managers do a better job.

- Career growth: to develop skills, identify growth opportunities, and expand employees’ vision of their future at the company.

- Serve as lightweight performance reviews: a feedback mechanism to gather inputs and summarize what the employee has accomplished since the last meeting in the context of the organization’s needs. (this is apart from an employee’s annual compensation/bonus review)

When workplace conversations become integral, managers evolve from taskmasters to teachers, coaches, and mentors. The approach transitions from the traditional autocratic to a democratic one.

Focus on value delivery, not task completion

While crossing off an item on a to-do list can be exciting, it is not a measure of success. OKRs focus on the value created and not task completion because of three main reasons:

- It promotes a results-focused culture and not one focused on tasks.

- If all the tasks were completed and nothing improved, it wouldn’t amount to much.

- Tasks are driven by an action plan which is just a series of hypotheses. It does not guarantee results. Value addition is the key. OKRs focus on the destination, not on the means to get there. By doing so, it encourages innovation.

Frequent recognition

Employee recognition remains an untapped resource for many organizations. According to a large-scale analysis conducted by Workhuman and Gallup, if a business of 10,000 doubled the number of employees who receive recognition, they could realize a 9% increase in productivity, amounting to almost $92 Mn in annual gains [16].

Recognition is among the three pillars of CFR. It is performance-based, horizontal and a powerful driver of engagement. Some of the best practices of recognition include:

- Peer-to-peer recognition: need not be formal – even unsolicited, unedited shout-outs from anyone in the organization to anyone else who’s done a remarkable job can go a long way in energizing employees and developing a culture of gratitude.

- Having established criteria – well-defined actions and results such as completion of special projects, achievement of company goals, or demonstrations of values.

- Sharing success stories: encourage sharing of success on platforms such as newsletters or company blogs.

- Making recognition frequent and attainable – hailing smaller accomplishments and other little things can make a positive impact.

- Tie recognition to company goals and strategies – customer service, innovation, teamwork, cost cutting— almost any organizational priority can be supported by a timely shout-out.

Sources

1. “Measure What Matters: How Google, Bono, and the Gates Foundation Rock the World with OKRs”. John Doerr, https://www.amazon.com/Measure-What-Matters-Google-Foundation/dp/0525536221. Accessed 23 May 2024.

2. “The Beginner’s Guide to OKR”. Felipe Castro, https://felipecastro.com/en/okr-tools/01_lp/. Accessed 23 May 2024.

3. “Implementing Strategic Goals for Organizational Success”. Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/sponsored/2022/09/implementing-strategic-goals-for-organizational-success. Accessed 24 May 2024.

4. “Introduction”. Edwin A. Locke, Ph.D., https://edwinlocke.com/. Accessed 24 May 2024.

5. “Impact of Management by Objectives on Organizational Productivity”. Robert Rodgers and John E. Hunter , https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232469309_Impact_of_management_by_objectives_on_organizational_productivity. Accessed 24 May 2024.

6. “The Pinto Memo: ‘It’s Cheaper to let them Burn!’”. The Spokesman-Review, https://www.spokesman.com/blogs/autos/2008/oct/17/pinto-memo-its-cheaper-let-them-burn/. Accessed 29 May 2024.

7. “The aligned organization”. McKinsey and Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/the-aligned-organization. Accessed 30 May 2024.

8. “National Library of Medicine”. Benjamin Harkin, Thomas L Webb, Betty P I Chang , Andrew Prestwich, Mark Conner, Ian Kellar, Yael Benn, Paschal Sheeran, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26479070/. Accessed 30 May 2024.

9. “Google Says It Still Uses the ’20-Percent Rule,’ and You Should Totally Copy It”. Inc., https://www.inc.com/bill-murphy-jr/google-says-it-still-uses-20-percent-rule-you-should-totally-copy-it.html. Accessed 30 May 2024.

10. “WorkBoard Enables Users of Any Skill Level to Dynamically Create OKR Dashboards and Business Reviews”. WorkBoard, https://www.workboard.com/workboard-in-the-news/pr-2020may04.php. Accessed 30 May 2024.

11. “What Really Motivates Workers”. Teresa M. Amabile, Harvard Business School, https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=37331. Accessed 30 May 2024.

12. “A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance”. Edwin Locke and Gary P. Latham, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232501090_A_Theory_of_Goal_Setting_Task_Performance. Accessed 30 May 2024.

13. “Ten things we know to be true”. Google, https://about.google/philosophy/. Accessed 02 Jun 2024.

14. “The Performance Management Revolution”. Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2016/10/the-performance-management-revolution. Accessed 03 Jun 2024.

15. “Laszlo Bock: Divorce Compensation from OKRs”. What Matters, https://www.whatmatters.com/articles/laszlo-bock-divorce-compensation-from-okrs. Accessed 03 Jun 2024.

16. “From Praise to Profits: The Business Case for Recognition at Work”. Gallup and Workhuman, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20230328005814/en/New-Workhuman-Gallup-Study-Finds-Employee-Recognition-Can-Help-Businesses-Gain-Over-90-Million-in-Increased-Productivity. Accessed 03 Jun 2024.