Understanding customers is not enough. Firms gain a competitive advantage only when they do better than their competitors in satisfying the target consumers’ needs.

Competition is one of the most inevitable forces in the business world. No matter how big or small, a firm has competitors in the industry and the strategies of these competitors affect its business strategy.

Ever since the seminal works of Porter (1980, 1985), sophisticated competitive analysis is considered a crucial cornerstone of the strategic decision process. Identifying competitors, evaluating their strategies, and determining relative strengths and weaknesses are crucial steps to business success.

What is a Competitive Analysis

Competitive Analysis is the process of identifying key competitors, assessing their objectives, strategies, strengths and weaknesses, and reaction patterns and selecting which competitors to attack or avoid.

In strategic management, “competitive” analysis is often interchangeably used with the term “competitor” analysis which is a bit narrower in scope compared to the former.[1]

Importance of competitive analysis

The following reasons have led to a greater need for competitive analysis, making it a necessity rather than a desired goal:

Cheap and quick access to information

Keeping key competitive information out of sight from competitors has become difficult. With the rapid rise of information access, big data tools, and enhanced analytics, competitor’s reaction times have shrunk.

Changing sociocultural value systems

It is now easier than ever for a competitor to attract a firm’s talent as companies show less loyalty to their employees, and by extension, employees show less loyalty to their employers. Keeping proprietary information safe has become increasingly difficult.

Traditional competitive structure and advantages no longer work

Prominent industries of the twentieth century were resource-based (such as manufacturing, steel, telecom etc.) and could achieve a competitive edge through scale economies, segment entrenchment, and first-mover advantages.

Strong entry barriers such as capital, machinery and know-how kept competition at bay. Most of the rivals were known and disruptions were rare.

In contrast, modern businesses depend on factors such as intellectual property, data, innovation, knowledge, brand equity, proficient R&D teams, and skill sets.

Disruptive technologies can swiftly remove entry barriers while rendering well-established business models obsolete. For example, film-based photography was replaced by digital cameras which are now replaced by smartphones.

While the generic strategies of cost, differentiation, and focus described by Michael Porter are still conceptually fruitful, they are hard to achieve and sustain.

Customers are better informed and have more sophisticated needs

With access to significantly more information, customers are less likely to be swayed

by an emotional appeal. They perform hard-nosed research before striking a deal, especially

with big-ticket items.

As with B2B markets, buying habits are less ingrained, and purchases are increasingly based on specification, cost, and value. Bad news travels fast, and the presence of customer pressure groups, Internet blogs, and vociferous word-of-mouth channels can quickly damage a brand.

Performing competitive analysis

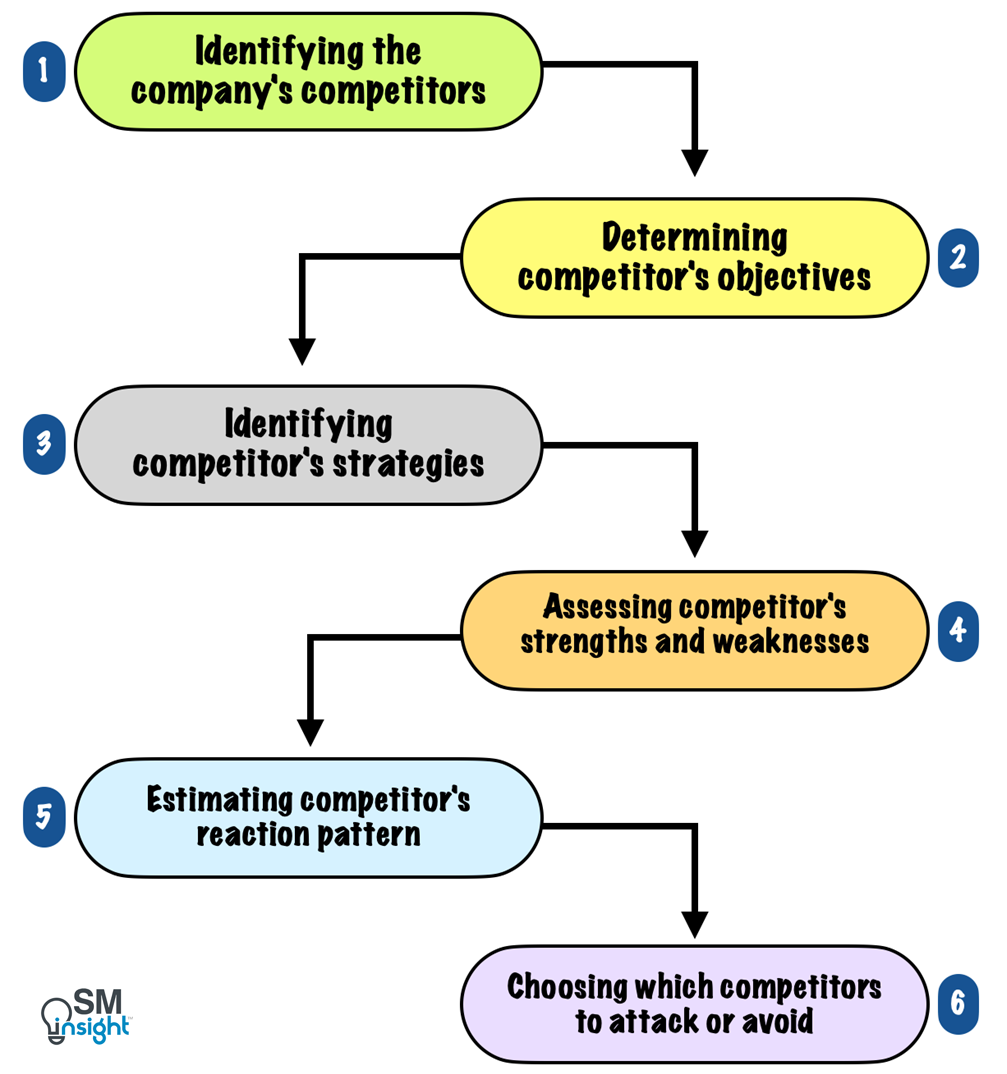

Competitive analysis involves the following steps:

1. Identify the company’s competitors

Defining broadly, a firm’s competitors are all those who fight for the same customers’ spending power.

On the surface, identifying competitors can look straightforward. For example, Boeing knows Airbus is its strongest competitor, and Intel knows it is competing with AMD.

But as we will see, there are different kinds of competitors and identifying them can be tricky as not every competitor is immediately obvious:

Brand competitors

These are the most obvious ones. They are firms that offer similar products or services to the same customers at similar prices.

For example, Ford will consider Toyota as its competitor but not Rolls-Royce even though they sell similar products because the latter sells at a very different price point.

Product competitors

This is a much broader way of defining competition and includes firms that make the same product or class of products.

For example, Volvo would consider not only other car manufacturers but also the makers of trucks, motorcycles, or even bicycles, as they belong to the same category of products.

Industry competitors

These are competitors that offer similar products or services but differ in some important ways, such as organization size, the precise type of product offering, or the target market.

Industry competitors offer a product or class of products that are close substitutes for one another, thus making the demand interlinked.

The rise of Netflix (and the fall of Blockbuster) is a classic example of industry competitors.

In 2004, Blockbuster’s physical-store-based DVD rental business did great until Netflix introduced the mail-order subscription model followed by online streaming which eventually bankrupted Blockbuster.

Form (or market view-based) competitors

Form competitors offer products or services which fulfill the same customer needs as the focal firm even though the products or services are very different in form or technology. They address the same unmet needs of the customers.

For example, Heineken might consider Carlsberg, Budweiser, and other brewers as its competition. But the primary customer “need” it addresses is “social drinking”. Hence, Heineken’s competition could come from a very distinct class of products, such as energy drinks, alcopops or health drinks that could satisfy the same need.

The form-based concept of competition opens a company’s eyes to a broader set of actual and potential competitors and leads to better long-run market planning.

Taking a customer-oriented view of the market is hence critical to avoiding ‘competitor myopia’ where the immediate competition blinds a company to latent competitors who can destroy the old ways of doing business.

Generic Competitors

As customers have limited time and money to spend, competition can sometimes arise from unrelated areas. For example, a fine dining restaurant could compete with a movie theatre for the same share of customers’ time and, hence, money.

Other ways of classifying competition

A firm’s competitors can also be classified as direct, indirect, and future competitors.

- Direct competitors are businesses that offer identical or similar products or services as the focal firm. These represent the most intense form of competition as customers often compare prices, features, and deals as they shop.

- Indirect competitors are businesses that offer products and services that are close substitutes. They target the firm’s markets with the same or similar value proposition but with a different product. Industry and form competitors usually fall in this category.

- Future competitors are existing companies that are not yet in the marketplace that the firm intends to occupy but could move there at any time. Indirect competitors are obvious candidates for future competition.

A rule of thumb

While almost every other firm could appear to be a potential competitor in some way, in practice, a firm cannot dedicate resources to monitor all of them.

Studies have shown that the biggest competitive threat is likely to come from firms that have some or all the following characteristics:

- They sell to the same type of customers as the focal firm.

- They have similar or lower-cost supply and distribution channels.

- They have similar or superior technologies.

- Their target market significantly overlaps that of the focal firm.

To make the best use of their resources, firms can use this as a rule of thumb to narrow their focus on the most likely competitors.

2. Determine competitor’s objectives

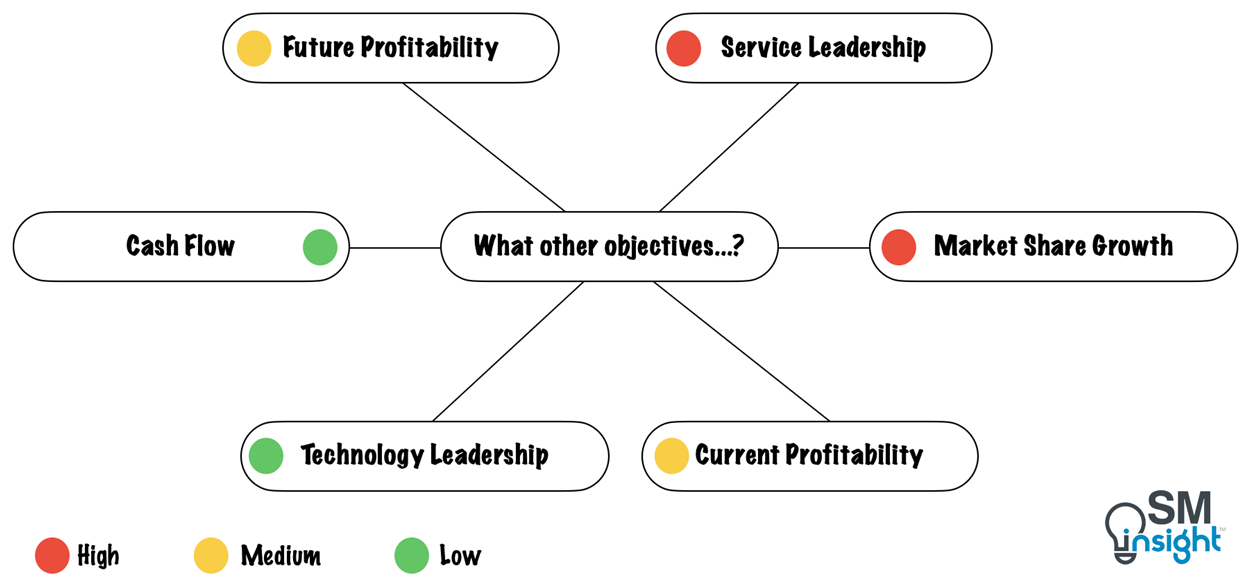

While the high-level objective of all competitors is to maximize profits, the actions through which they achieve it can vary.

Firms can differ in the emphasis they put on short-term versus long-term objectives. Some are oriented towards ‘satisfying-customer’ rather than ‘maximizing’ profits. Hence, marketers must look beyond competitors’ profit goals as competitors can have a mix

of objectives, each with differing importance:

Knowing a competitor’s objectives reveals whether it is satisfied with its current situation and how it might react to competitive actions.

For example, a company that pursues low-cost leadership will react strongly to a competitor’s cost-reducing manufacturing breakthrough vs. an increase in advertising spend.

3. Identify competitors’ strategies

Competitors can be sorted into strategic groups – firms that follow the same (or similar) strategy in a given target market.

For example, in the auto industry, Ford, Honda and Toyota belong to the same strategic group producing medium-priced mass-market cars supported by good service. On the other hand, brands like Mercedes, Maserati and Jaguar belong to a different strategic group. They produce a narrower but premium line of cars and charge more.

Strategic group identification can provide important insights – if a firm intends to enter one of the strategic groups, it must develop some strategic advantage over existing players.

While competition is most intense within a strategic group, it can also extend among groups due to several factors:

- Some strategic groups may appeal to overlapping customer segments.

- Customers may not see much difference in the offers of different groups.

- Members of one strategic group might expand into new strategy segments. For example, the Lexus brand of Toyota competes with the likes of Mercedes.

A company needs to look at all the dimensions that identify strategic groups within the industry. It needs to know each competitor’s product quality, features and mix, customer services, pricing policy, distribution coverage, sales force strategy, and advertising and sales promotion program.

4. Assessing competitors’ strengths and weaknesses

The ability of a competitor to carry out strategies and reach its goals depends on its resources and capabilities. Hence, marketers need to identify each competitor’s strengths and weaknesses.

But collecting this data can be hard.

For example, industrial goods companies may find it hard to estimate competitors’ market shares because they do not have the same syndicated data services that are available to consumer-packaged goods companies or e-commerce firms.

Companies normally learn about their competitors’ strengths and weaknesses through

secondary data, personal experience, and hearsay. Primary marketing research with customers, suppliers and dealers is also a good way to collect information.

Benchmarking[3] is another, such tool that helps a company identify its relative strengths and weaknesses. It is the process of comparing a company’s products and processes to those of competitors or leading firms in other industries to find ways to improve quality and performance.

In searching for competitors’ weaknesses, a company must challenge its assumptions for validity. For example, a competitor can believe they produce the best, but this may no longer be true.

Some competitors can also be victims of beliefs that are no longer valid – for example, ‘customers prefer full-line companies’ or ‘the sales force is the only important marketing tool’.

Identifying and understanding these assumptions can enable a company to capitalize on them strategically.

5. Estimating competitors’ reaction patterns

Marketing managers need a deep understanding of a given competitor’s mentality if they want to anticipate how that competitor will act or react.

A competitor’s reaction could depend on several factors, such as:

- A belief that their customers are loyal.

- They may be slow to notice a move.

- Lack of resources to react.

- Choosing to react only to certain types of assault (For example, to price cuts but not aggressive advertising).

In some industries, competitors live in relative harmony; in others, they fight constantly.

For example, social networks compete aggressively for users. These platforms are quick to borrow features from one another. Instagram copied the “stories” feature from Snapchat.[4] Similarly, YouTube copied “shorts” from TikTok.[5]

Having a fair idea about competitor’s reaction patterns gives clues on how best to attack or how best to defend the company’s current positions.

6. Choosing competitors to attack or avoid

Intelligence gathered in previous steps equips a company to decide which competitors to attack or avoid.

Strong or Weak Competitors

Most companies prefer to compete against weak competitors. This requires fewer resources and less time. But in the process, the firm may gain little.

In contrast, strong competitors can be good “grinding stones” for sharpening a company’s abilities and providing better returns when successful.

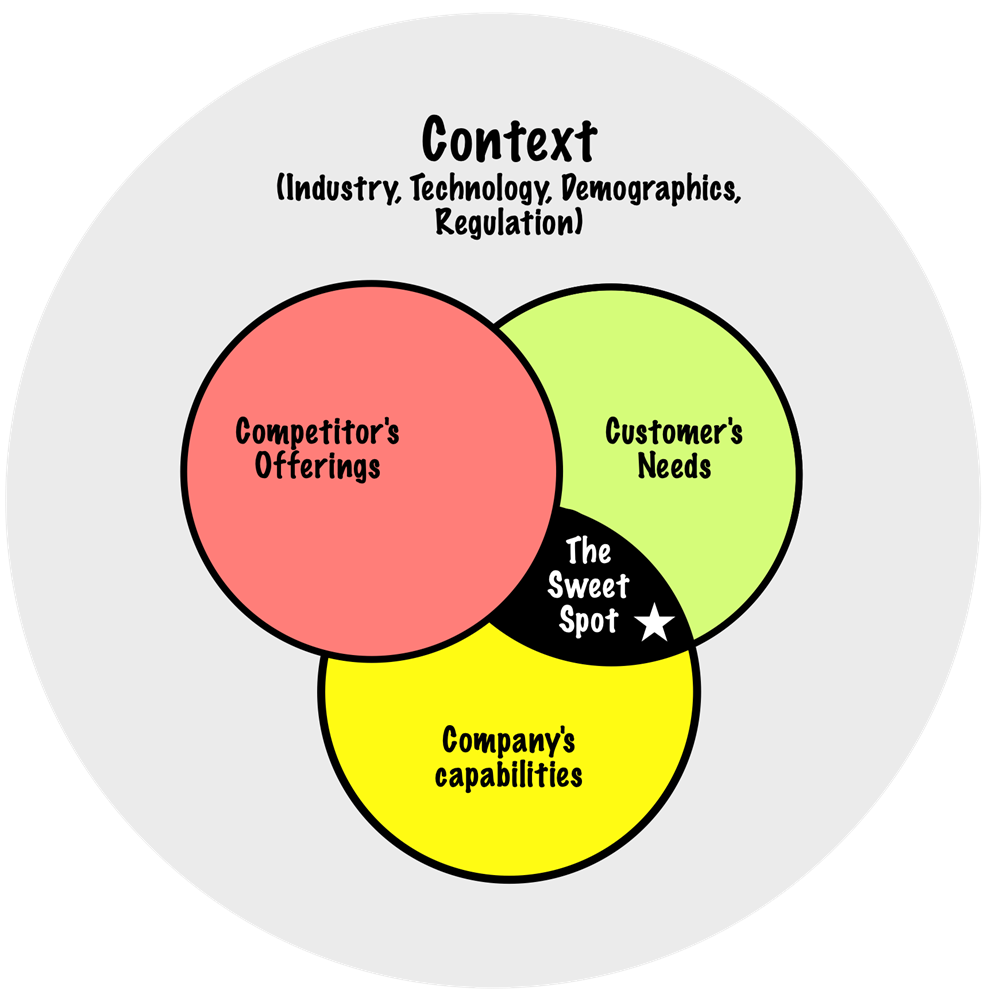

Customer Value Analysis[6] which involves identifying major attributes that customers value is an effective tool to assess what competitors to choose.

The key to gaining a competitive advantage is to examine how the company’s offer compares to that of its competitors in each segment. This way, the company can find a place in the market where it meets the customers’ needs in a way that rivals can’t. This is the strategic sweet for a company to be in.

Close or Distant Competitors

Most companies compete with close competitors, i.e., firms that closely resemble them.

Given the strategic advantages they bring (see below), companies must avoid aggressively ‘eliminating’ close competitors.

- They help increase the total demand

- They share the costs of market and product development

- They help legitimize and establish new technology

- Some serve less attractive segments or lead to more product differentiation

- They improve bargaining power against labor or regulators

Good or Bad Competitors

“Good” competitors play by the rules of the industry. They favor stability, set reasonable prices, motivate others to lower costs or improve differentiation, and accept a reasonable level of market and profit share.

In contrast, bad competitors take huge risks, play by their own rules, and disrupt the market.

Elon Musk-backed SpaceX is a classic example of bad competition. In an otherwise mature and stagnant industry with limited players, SpaceX drastically lowered the cost of spaceflight through innovations such as reusable stages and fairings.

NASA’s space shuttles, which were retired in 2011, cost an average of $1.6 billion per flight, or nearly $30,000 per pound of payload. In contrast, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket typically charges around $62 million per launch, or around $1,200 per pound of payload to reach low-Earth orbit.[8]

Finding Uncontested Market Spaces

Firms can also go for a relatively bolder and distinct strategy, best known as the “Blue Ocean Strategy,” by creating products and services for which there are no direct competitors.[9]

Such strategic moves, termed ‘value innovation’ lead to powerful leaps of value creation for both the firm and its buyers, generating new demand and rendering rivals obsolete.

Tools and techniques for Competitive analysis

The importance of understanding competitors has been widely acknowledged in the industry as well as academia. This has led to the development of numerous tools and techniques for competitive analysis.

Some of the most commonly used tools and techniques are briefly discussed:

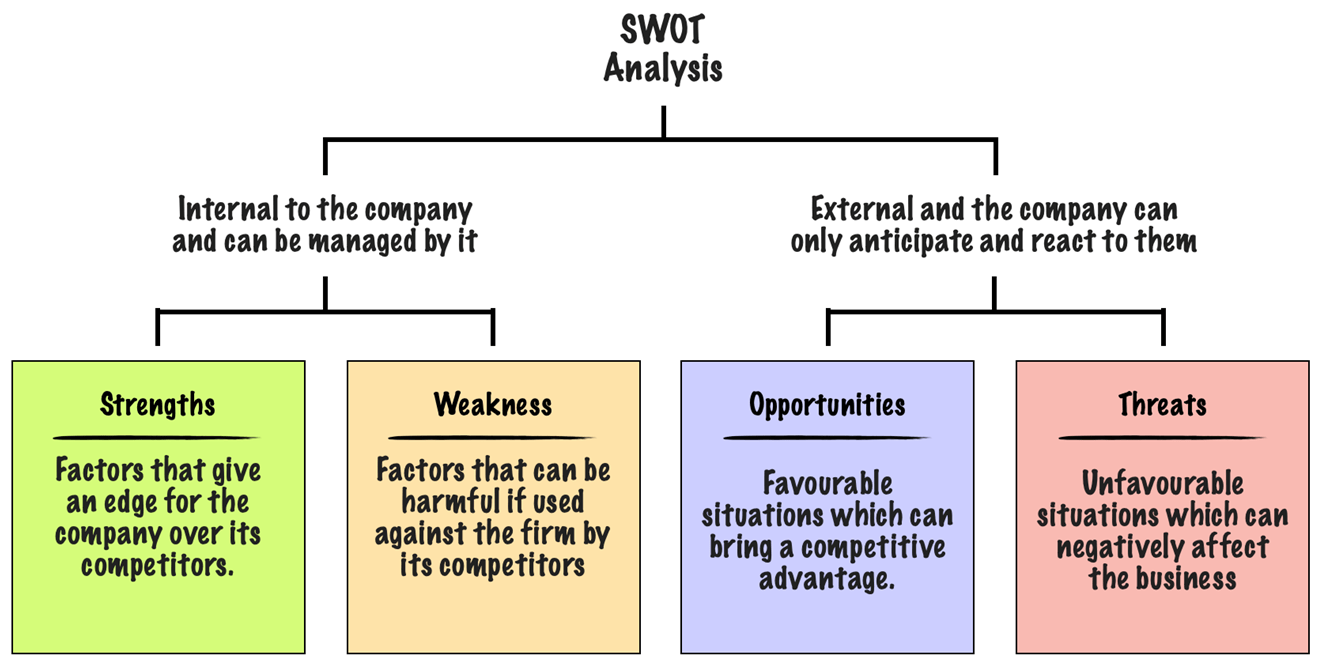

SWOT Analysis

SWOT Analysis is a strategic audit tool that takes both internal and external perspectives to distill the findings into critical organizational strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats:

SWOT analysis facilitates competitive analysis by pinpointing an organization’s internal strengths and weaknesses and allowing for an objective assessment of its competitive capabilities. It also highlights external opportunities and threats, offering insights into the competitive landscape.

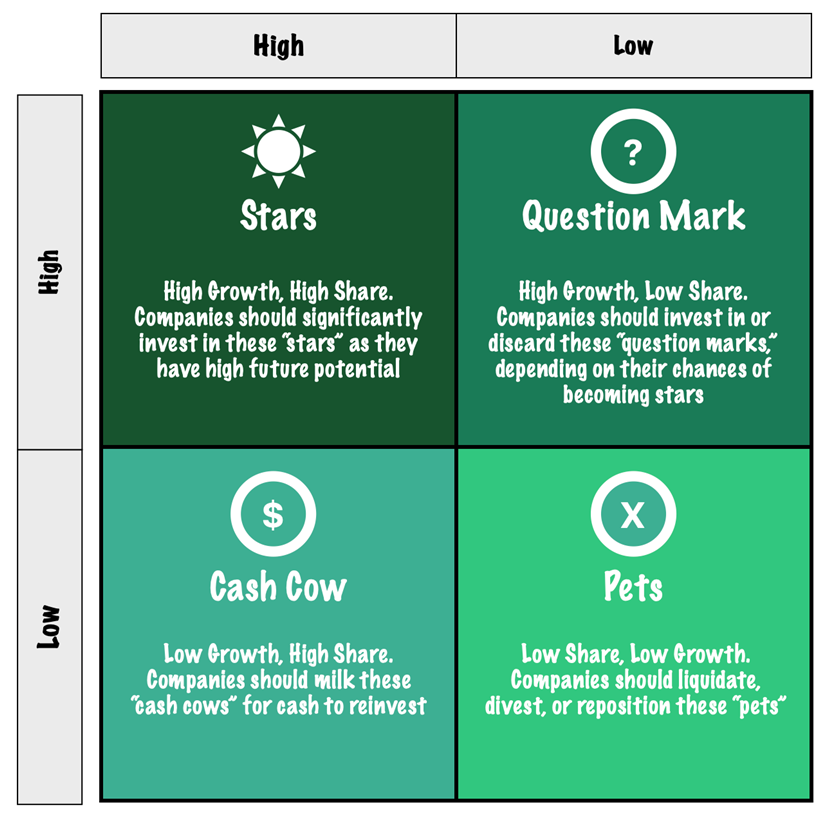

Growth-Share Matrix (BCG Matrix)

The Growth Share Matrix is a portfolio management framework that helps companies decide how to prioritize their different businesses. It classifies a company’s business portfolio into four categories based on industry attractiveness (growth rate of that industry) and competitive position (relative market share):

By assigning each of the company’s businesses to one of the above four categories, the BCG matrix helps decide where to focus resources and capital to generate the most value, as well as where to cut losses.

Since the matrix is built on the logic that market leadership results in sustainable superior returns, the market leader obtains a self-reinforcing cost advantage that competitors find difficult to replicate.

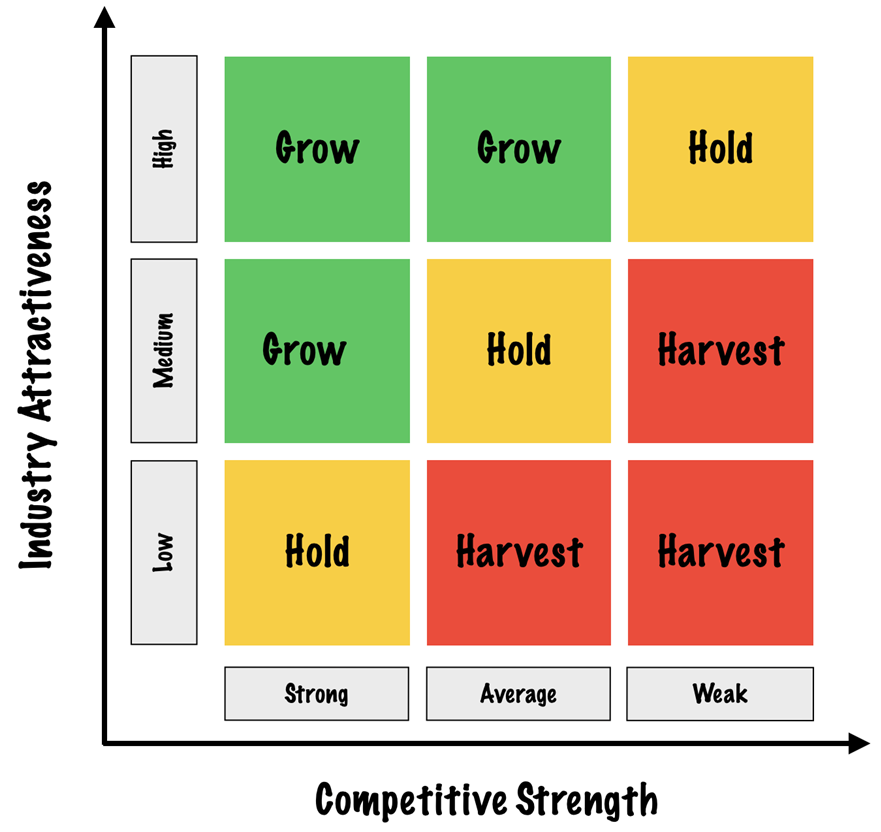

GE McKinsey Matrix (Nine-Cell Matrix)

The Nine-cell matrix, while similar to the BCG matrix, is a more sophisticated business portfolio framework.

Unlike the BCG Matrix which has been criticized for its reliance on a single dimension for analysis, the Nine-cell matrix uses multiple variables to determine the two dimensions: Industry attractiveness, and Competitive strength.

The horizontal axis of this matrix represents competitive strength and is divided into High, Medium, and Low. It measures the business’s competitiveness among its rivals and helps indicate a business’s ability to compete in the industry.

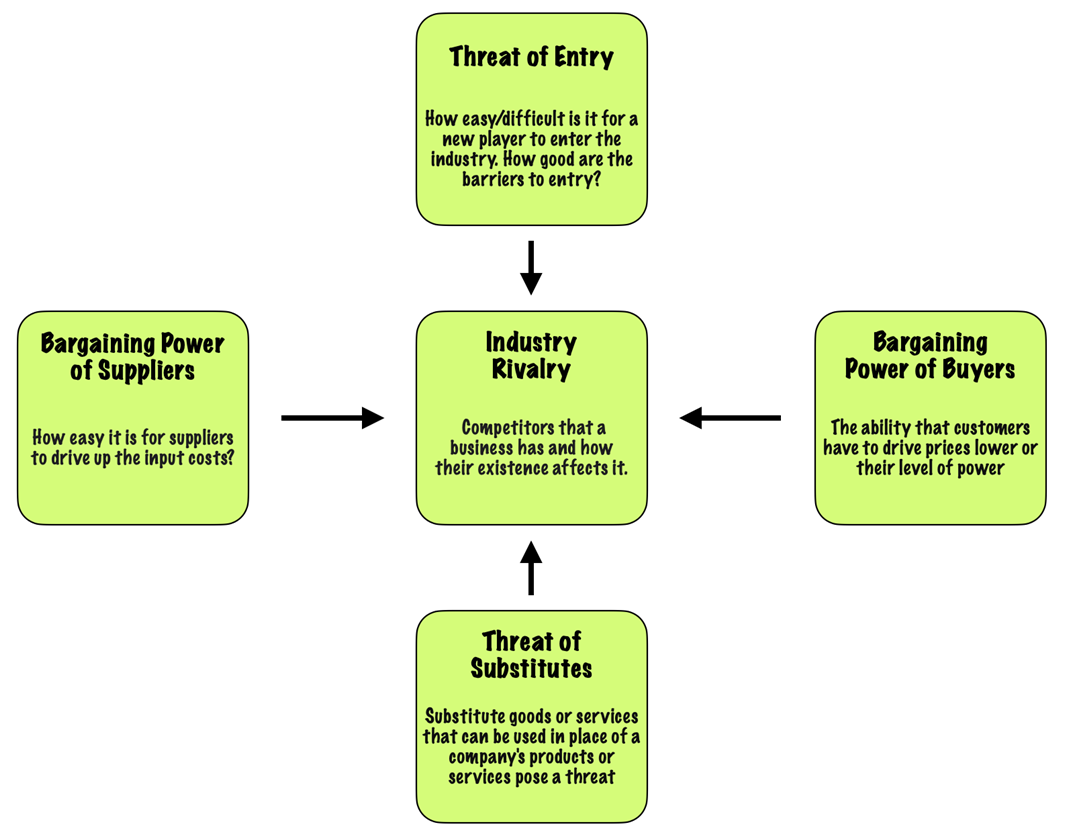

Porter’s Five Forces model

In 1979, Michael Porter developed the Five Forces model – a framework for analyzing a company’s competitive environment. The model helps determine the forces that shape an industry structure and the level of competition in that industry.

Five Forces work well for businesses that are starting or looking forward to starting a new marketing strategy. It gives a better understanding of the industry’s competitive structure.

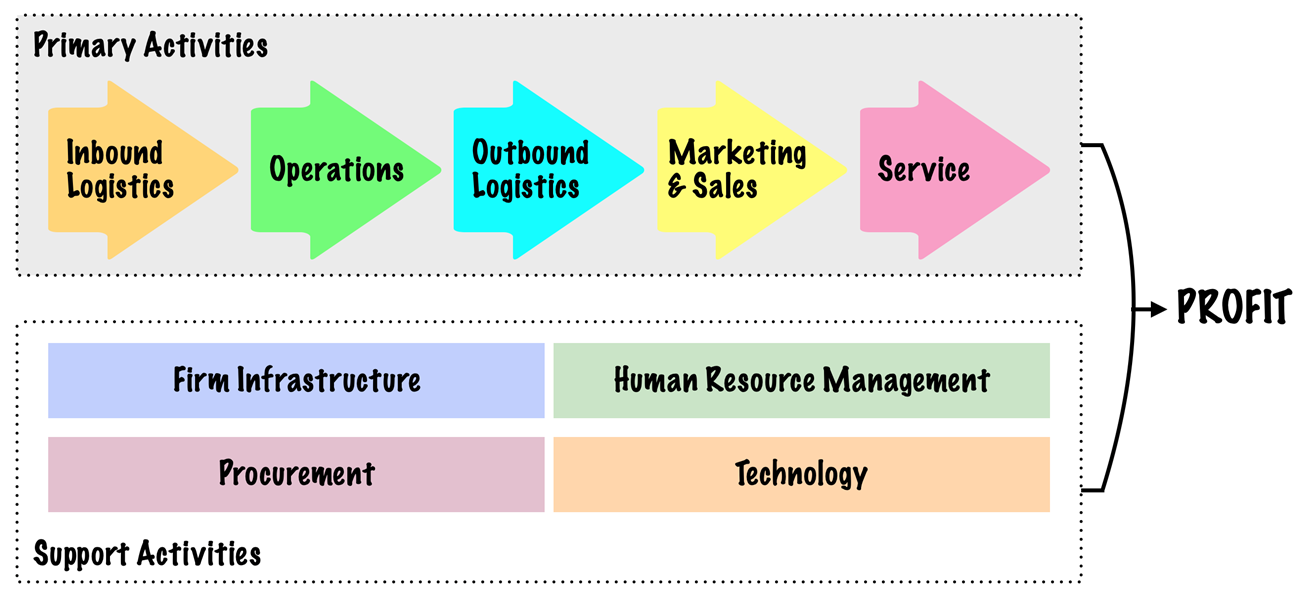

Value Chain Analysis

Value Chain Analysis forms of competitive advantag is a means of evaluating each of the activities in a company’s value chain to understand how each step in the process adds value.

The tool compels a company to question the importance of each of its activities by benchmarking them against competitors. The process helps realize various forms of competitive advantages, such as cost reduction or product differentiation.

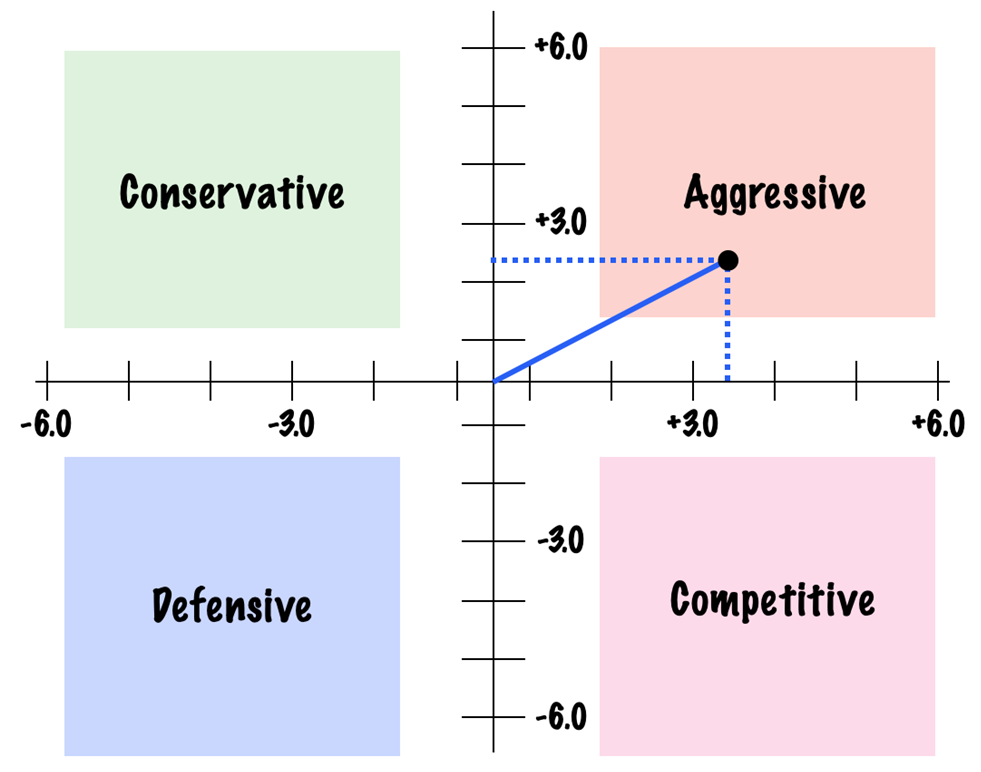

Space Matrix

The Strategic Position and Action Evaluation matrix (SPACE matrix) is a tool that focuses on strategy formulation specifically related to the competitive position of an organization.

The matrix is broken down into four quadrants (see below), each of which suggests a different type or nature of a strategy.

The matrix analyzes functions based on two internal (Financial strength and Competitive advantage) and two external (Environmental stability and Industry strength) strategic dimensions to determine the organization’s strategic posture in the industry.

By calculating the importance of each of these dimensions, the SPACE matrix places them on a Cartesian graph with X and Y coordinates. The quadrant in which a company’s final score lies helps find the optimum strategy.

Space matrix can be used as a tool to calibrate a company with respect to its competition and as a basis for other tools like SWOT, Industry analysis or accessing strategic alternatives.

EFE and IFE Matrices

The External Factor Evaluation (EFE) matrix is a strategic management methodology that assesses and evaluates an organization’s external opportunities and threats. Similarly, an Internal Factor Evaluation (IFE) evaluates a firm’s internal environment and reveals its strengths as well as weaknesses

| Key External Factors | Weight | Rating | Weighted Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opportunities | |||

| New immigration laws abolish the restrictions for immigrants to live and work freely in the country. | 0.02 | 1 | 0.02 |

| A government increases budget spending for our products. | 0.17 | 4 | 0.68 |

| New product market, worth $1 billion a year, could be introduced for the consumers. | 0.05 | 4 | 0.20 |

| Consumers are 20 % more likely to by the products that share the same ecosystem. | 0.12 | 4 | 0.48 |

| We have patented the technology that increases the quality of our products and lowers the amount of the materials needed | 0.03 | 3 | 0.09 |

| Our largest competitor is selling their subsidiary in TV market. | 0.14 | 2 | 0.28 |

| Threats | |||

| Tax rates will increase by 10% for the polluting companies. | 0.06 | 2 | 0.12 |

| Due to the fast economic growth credit availability will tighten. | 0.04 | 4 | 0.16 |

| Credit rates are growing by 5%. | 0.02 | 2 | 0.04 |

| Natural disasters disrupt our suppliers’ or our operations. | 0.08 | 3 | 0.24 |

| Rivalry in the market is intensifying. | 0.12 | 4 | 0.48 |

| Competitor is pursuing horizontal integration strategy. | 0.10 | 3 | 0.30 |

| Inflation has increased to 6%. | 0.05 | 2 | 0.10 |

These matrices serve as competitive benchmarking tools to compare a company’s EFE/IFE matrix with those of its key competitors. This helps in understanding how the company fares relative to its rivals and in identifying areas where it can gain a competitive edge.

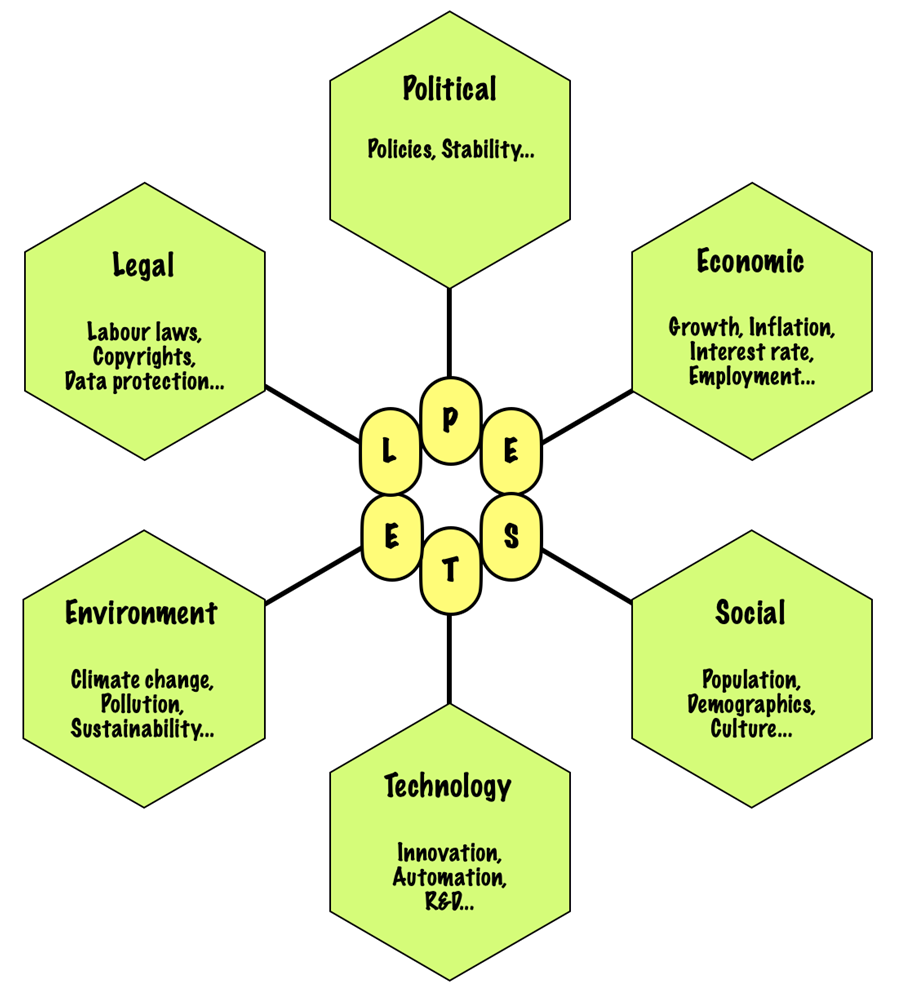

PEST & PESTEL Analysis

A PEST analysis looks at a company from the lens of political, economic, social, and technological factors – the key externalities that can affect its activities and performance. PESTEL adds Legal and Environmental factors to the PEST model.

Using the tool shows how a company and its competitors face various challenges and advantages through the lens of each of the PESTEL perspectives. It also helps collect competitor data and determine how they handle the challenges presented in each of the perspectives.

Competitor Profile Matrix (CPM)

CPM helps companies assess themselves against their major competitors using the critical success factors for that industry. Constructing the CPM involves three steps:

- Find the Critical Success Factors (CSFs) for a company and attach weight to those factors according to their relative importance.

- Identify major competitors and rate each competitor, including the company itself on each of the CSFs

- Multiply the weight by the rating for each factor to get a weighted score. Then add each company’s weighted scores to get a total weighted score.

| Critical Success Factors | Weight | Company | Competitor 1 | Competitor 2 | |||

| Innovation | 25% | 2 | 0.5 | 5 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Advertising | 20% | 4 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Brand Name | 20% | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.4 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Productivity | 15% | 5 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.8 |

| Customer Service | 10% | 3 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Price Competitiveness | 5% | 1 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.2 |

| Technological Competence | 5% | 5 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.2 |

| Weighted Average Score | 100% | 2.9 | 3.8 | 2.7 | |||

This, in summary, competitive analysis helps decision makers understand who competitors are and what the market structure is. The process requires paying close attention to each competitor’s apparent objectives, resources, competitive moves, strengths, and weaknesses.

A well-executed competitive analysis empowers organizations to formulate robust strategies, ultimately enhancing their ability to succeed in the market.

Sources

1. “Competitor Analysis in Strategic Management: Is it a Worthwhile Managerial Practice in Contemporary Times?”. Alex Yaw Adom, Israel Kofi Nyarko and Gladys Narki Kumi Som, https://iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JRDM/article/view/33186. Accessed 28 Sep 2023

2. “Principles of Marketing”. Philip Kotler, Veronica Wong, John Saunders and Gary Armstrong, https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00HK38B3I?ref_=cm_sw_r_cp_ud_dp_42BGW75WED62JADPCZ0Z. Accessed 28 Sep 2023

3. “Benchmarking”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/benchmarking/. Accessed 03 Oct 2023

4. “Snapchat was ‘an existential threat’ to Facebook — until an 18-year-old developer convinced Mark Zuckerberg to invest in Instagram Stories”. Insider, https://www.businessinsider.com/how-developer-mark-zuckerberg-invented-instagram-stories-copied-snapchat-2020-4?IR=T. Accessed 30 Sep 2023

5. “YouTube Shorts copies TikTok again with voiceover narration”. Engadget, https://www.engadget.com/youtube-shorts-voiceover-narration-190351673.html. Accessed 30 Sep 2023

6. “Customer Value Analysis (CVA)”. CIO Wiki!, https://cio-wiki.org/wiki/Customer_Value_Analysis_(CVA). Accessed 03 Oct 2023

7. “Can You Say What Your Strategy Is?”. Harvard Business Rveiew, https://hbr.org/2008/04/can-you-say-what-your-strategy-is. Accessed 01 Oct 2023

8. “To cheaply go: How falling launch costs fueled a thriving economy in orbit”. NBC News, https://www.nbcnews.com/science/space/space-launch-costs-growing-business-industry-rcna23488. Accessed 03 Oct 2023

9. “Blue Ocean Strategy”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/blue-ocean-strategy/. Accessed 30 Sep 2023