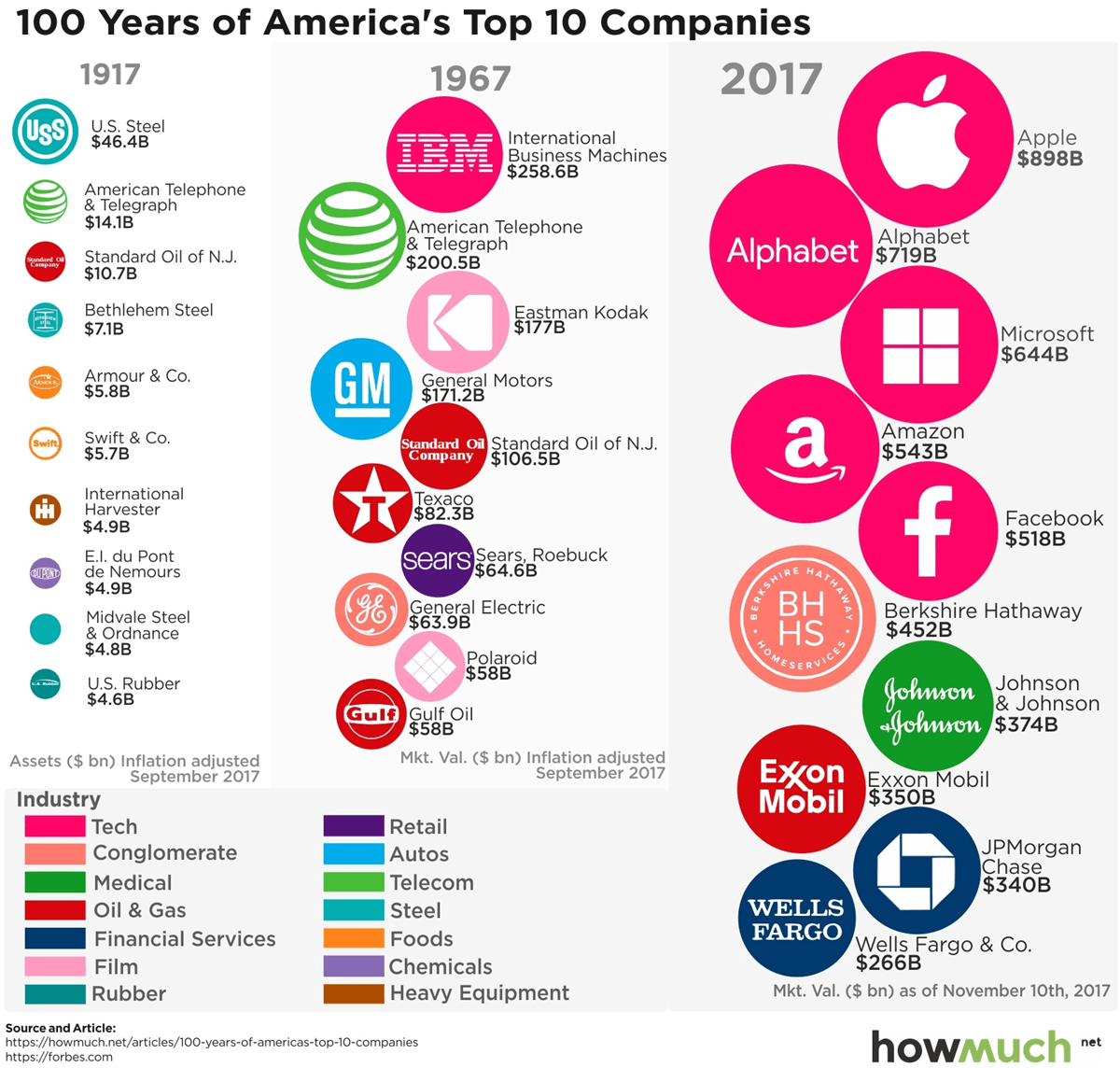

Few businesses that have stuck to their traditional products and markets have managed to grow in the long term. Over the past century, America’s most valued companies that made it to Forbes’s top ten were very different when compared across the years 1917, 1967 and 2017:

Data suggests that merely to survive the race of innovation and competition, a company must go through continuous growth and change. To improve its position, it must do it twice as fast.

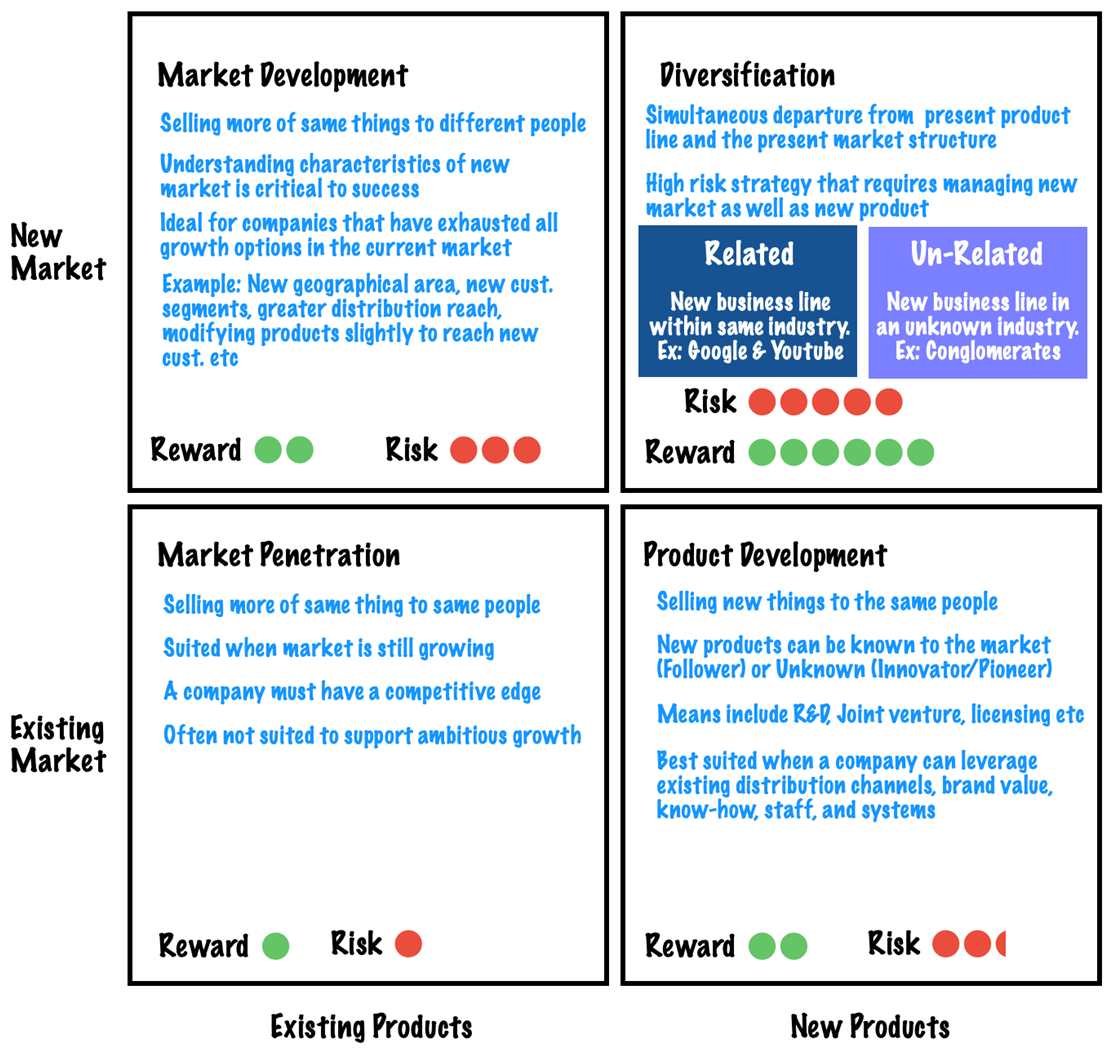

Evaluating growth strategies with Ansoff Matrix

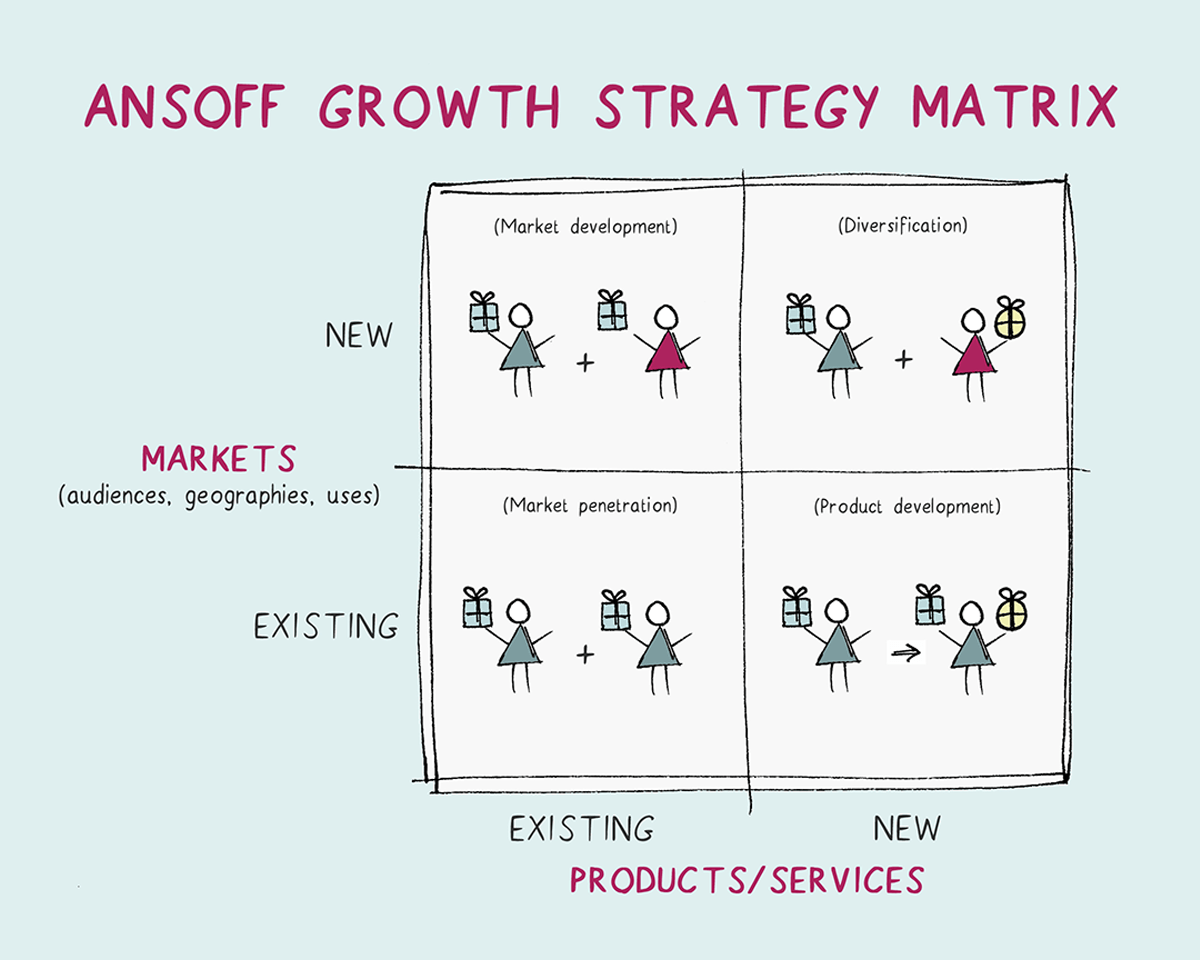

The Ansoff Matrix, also known as the Product-Market Expansion Grid, is a tool used to evaluate growth strategies. It was developed by H. Igor Ansoff[2], a Russian-American mathematician and business leader, dubbed the father of strategic management. His work was first published in Harvard Business Review in 1957[3].

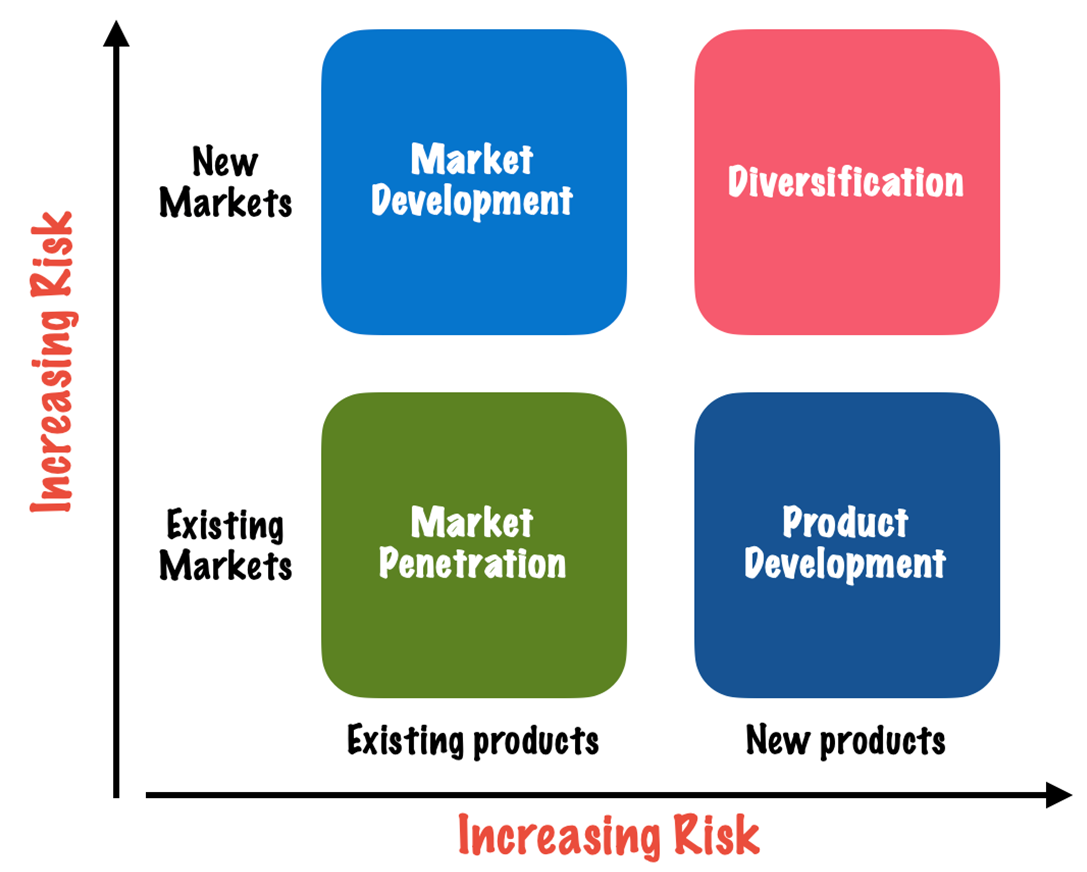

Using a 2 x 2 grid, the Ansoff matrix lays out the four basic growth alternatives open to any business.

A business can pursue either any or all of these strategies which are: increase market penetration, market development, product development and diversification:

Market penetration strategy

This strategy involves increasing efforts to grow sales without departing from the original product-market strategy. Simply put, this is an approach where a company tries to sell more of the same things to the same people.

Out of the four options, this is the one with the lowest risk as there are no substantial changes involved and the company continues to do what it is already doing, only better.

Under this strategy, business performance can be improved in two ways: by increasing the volume of sales to present customers or by finding new customers within the same market for existing products.

Typical market penetration efforts include:

- New marketing and advertising efforts.

- Refined pricing.

- Offering incentives, discounts, or loyalty programs to encourage repeat purchases.

- Improved distribution (focus on improving/expanding channels).

- Productivity improvements.

An increased market penetration strategy is well-suited to organizations that find themselves operating in a large and growing market where their offerings have a competitive advantage over rivals. It is also relevant when the products are new and the benefits from factors such as economies of scale, learning effects, and network effects are yet to be fully realized.

Though the risks and investments are low, this strategy by itself is often insufficient to support ambitious growth plans. Beyond a point, a market cannot expand any further as there is a limit to what companies can sell to the same customers without changing products.

Product development strategy

In this strategy, a company remains in the same market but develops products that have new and different characteristics. In simple terms, it is about selling more things to the same people.

This is a medium-risk strategy requiring a company to develop additional skills and/or business processes to support the new offerings. Since the company (usually) has a sound understanding of the market, the risks are manageable.

There are two routes to pursue this strategy:

- Be the follower – Introduce products or services that are already known to the market but new to the business:

For example, in 2015, Apple launched its smartwatch, which quickly became the top-selling wearable device, boasting over 4.2 million units sold in the second quarter of that fiscal year. Although the smartwatch was a fresh addition to Apple’s product line, it was a familiar offering in the market, already established by brands like Garmin and Fitbit. - Pioneer (Innovator) – Introduce products that are new to the market.

Apple’s iPhone launch in 2007 was a groundbreaking innovation that combined music, phone, and internet communication into a single device. At the time, there was no direct precedent for such a device in the market. Apple took the pioneering approach, capitalized on its strength in technology and revolutionized the smartphone industry.

A company can choose to develop its offerings in several ways such as own R&D efforts, by entering a joint venture, by purchasing other company’s products or through licensing.

Product development strategy is best suited to situations where a company can leverage its existing distribution channels, brand value, know-how, staff, and systems such that costs can be kept under control.

A drawback of this strategy is that unless a company can protect its offerings through patents and copyrights, the benefits are short-lived as competitors quickly catch up.

Market development strategy

Also referred to as the market extension strategy, this is about finding new markets for the same product or with minimal adaptation. It is basically selling more of the same things to different people.

This is also considered a medium-risk strategy, although the risks are slightly higher when compared to the product development strategy.

Efforts required to research and understand the needs of a new market, to become known, develop trust and therefore gain a meaningful market share is often greater than the effort of developing and launching a new product in a known market.

Typical risks include a failure to understand the characteristics of the new market, the competitive landscape, or the regulatory landscape. Many companies have tried and failed to implement this strategy.

Walmart’s entry into the German market in 1997 is a classic example. Known among the most successful retailers in the United States, Walmart opened its doors for business in Germany after acquiring the retail chain Wertkauf[7].

However, it failed to understand the characteristics of the German supermarket industry. Unlike the US, German regulators favoured smaller shops vs hypermarkets and did not permit the predatory pricing that worked in Walmart’s favour. A mismatch in culture was another factor – for example, employees were trained to smile at customers when they shopped while the customers found the practice embarrassing.

By 2006, Walmart made a rare admission of failure to convert German shoppers and regulators to its low-price, American-style trading and announced its plan to exit after taking a loss of $1bn[8].

Market development is the natural path for companies when they find that all opportunities in the existing markets have been exploited and there is no room to grow, even with the introduction of new products.

In the context of new market development, the word “new” can mean several things, such as:

- Geographical area (e.g.: domestic or international, a new country or a state).

- Customer segments.

- Sales outlets and distribution channels that expand reach (e.g.: going online from a store-only model).

- Rebranding/repackaging existing products with slight modifications (e.g.: Coca-Cola reached new markets by introducing low-sugar alternatives such as Coke Zero).

Nike’s transformation from a purely sportswear brand to a lifestyle brand that today includes athleisure – comfortable clothing suitable for both exercise and daily wear – is a classic example of an effective market development strategy.

According to Grand View Research, the worldwide athleisure market size is anticipated to reach USD 662.56 billion by 2030[9]. Being a leader, Nike is well-positioned to exploit this growth.

Diversification strategy

Diversification is the final alternative which calls for a simultaneous departure from the present product line as well as the present market structure.

It is the riskiest of the four strategies as it involves two unknowns. On one hand, there is the challenge of creating a new product with all the potential problems that may occur during the process, while on the other, developing a new market where there is little experience and whose characteristics may differ significantly from the currently known market.

Despite the risks, diversification is attractive and adopted by many firms because the rewards of a successfully executed strategy far exceed the risks. When done right, firms can achieve significantly higher growth and greater returns when compared to the other three conservative options.

In the long term, firms that diversify build resilience. For example, a change in regulatory norms in a geographic location or a particular market or a shift in customer preference may impact one segment or a product line but will have a limited impact on the overall revenue of a well-diversified firm.

The test for diversification

Michael Porter proposed three questions that a firm must answer to determine if it must pursue a proposed diversification[10]:

- How attractive is the industry that a firm is considering entering?

Unless the industry has strong profit potential, entering it may be very risky. Porter’s Five Forces Analysis[11] can help with this assessment. - How much will it cost to enter the industry?

Executives need to be sure that their firm can recoup the expenses that it absorbs in diversifying.

For example, when Philip Morris, a tobacco giant bought 7Up with plans to diversify into the soft drinks business, it paid four times what 7Up was worth. Making up these costs proved to be impossible and 7Up was sold in less than 10 years[12]. - Will the new unit and the firm be better off?

Unless at least one side gains a competitive advantage, diversification should be avoided. In the case of Philip Morris and 7Up, for example, neither side benefited significantly from joining together.

Firms that choose to diversify can look at two types of diversification strategies: related and unrelated which are explained in more detail:

Related diversification

A firm pursuing this strategy diversifies into business lines within the same industry which has important similarities with the firm’s existing industry/industries.

Businesses are considered related if they[13]:

- Serve similar markets and use similar distribution systems.

- Employ similar production technologies.

- Exploit similar science-based research.

Volkswagen’s acquisition of Audi and Disney’s purchase of the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) are examples of related diversification.

Firms that engage in related diversification aim to develop and exploit a core competency to become more successful. A core competency is a skill set that is difficult for competitors to imitate, can be leveraged in different businesses, and contributes to the benefits enjoyed by customers within each business.

For example, Google’s core competency lies in search technology and monetizing online advertising. When it acquired YouTube in 2006, Google extended its core competency into video streaming, allowing it to capitalize video content market and grow revenue.

Honda Motor Company is another good example of a firm leveraging its core competency through related diversification. Honda started out in the motorcycle business and developed a unique ability to build small and reliable engines. It applied its engine-building skills to diversify into cars, all-terrain vehicles, lawnmowers, boats and even generators.

But sometimes the benefits of related diversification that executives hope to enjoy are never achieved. For example, soft drinks and cigarettes are products that companies must convince consumers to buy through marketing activities such as branding and advertising.

On the surface, the acquisition of 7Up by Philip Morris seemed to offer the potential for Philip Morris to leverage its marketing competency, but the benefits never materialized.

Unrelated diversification

An unrelated diversification occurs when a firm enters an industry that lacks any important similarities with the firm’s existing industry/industries.

Such a firm pursues growth in markets where the main success factors are unrelated to each other and expects little or no transfer of functional skills among its various businesses.

Unrelated diversifications are hard to pull through and success is rare. Only companies that possess the skills and resources to analyze and manage the strategies of widely different businesses can consider unrelated diversification to be the best strategic option.

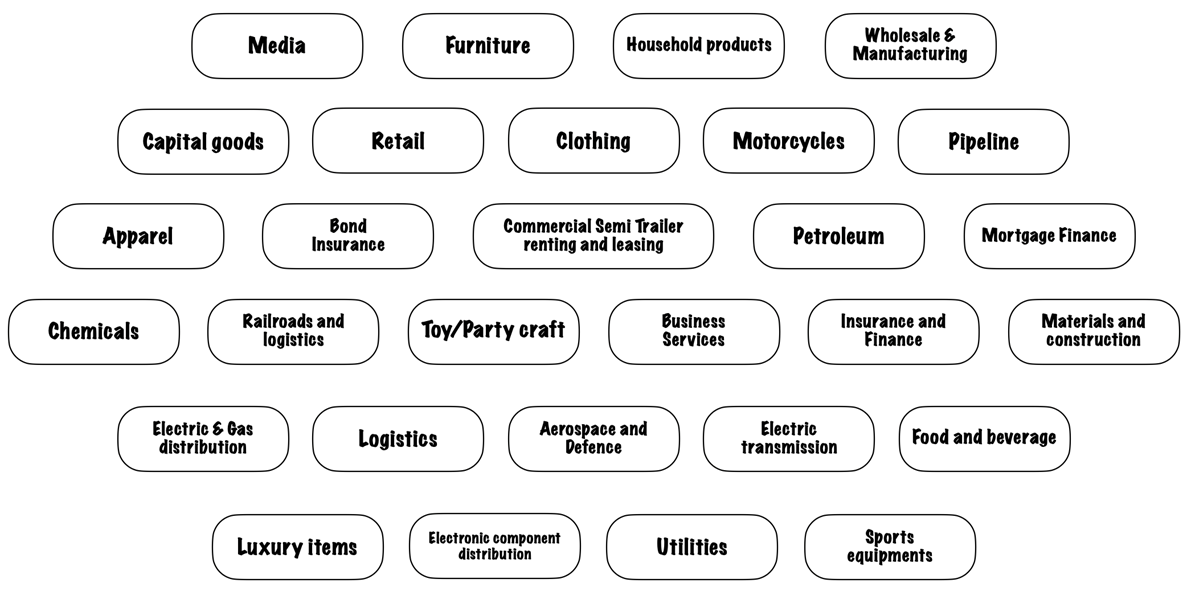

Berkshire Hathaway is a case in point, it owns controlling stakes in businesses spread over 35 sectors!

The Virgin Group is another example of unrelated diversification. Virgin started business as a record shop, first by mail order and in 1971 with a physical store and today, 50 years later it has diversified into a multinational venture capital conglomerate.

In the 1980s, Virgin entered the airline industry and applied its internal competence of providing excellent customer experience throughout its existing family of companies. At the time, great customer service was a rare quality in the airline industry, which was instead plagued by canceled flights, delays, and lost baggage. Virgin offered an advantage that was hard for competitor airlines to replicate and, therefore, could charge a price premium[16].

But unrelated diversification strategy is far from foolproof and there are examples of failure within the very same Virgin group.

The short rise and rapid fall of Virgin Cola in the 1990s after an ambitious, but unsuccessful plan to compete with Coca-Cola and Pepsi is a classic example of failure. Despite the growing fizzy drinks market, Virgin Cola managed a mere 3% market share on its home turf UK before exiting[17].

As of 2023, the group has a presence in over 20 sectors ranging from banking to aviation to commercial spaceflight[18].

Another risk that comes with the unrelated diversification strategy is the threat of losing brand strength by blurring the delivery of a single strong message.

When a firm diversifies into sub-brands that do not comfortably fit together, it must depart from the way it currently defines itself. This brings the risks of being perceived as a generic brand and not a leader.

Benefits and limitations of the Ansoff Matrix

Even though the Ansoff Matrix is over 60 years old, it remains an important tool in the strategic management toolkit. Even today, it is popular and widely used by organizations due to its simple, clear, and intuitively sensible design.

The matrix is particularly well suited for:

- Setting high-level corporate strategic direction-

- Helping management to consider all available growth options-

- Making apparent, the risks of pursuing different growth strategies – the greater the move from existing products or markets, the greater the risks-

However, the matrix is not suited for:

- Determine the detailed content and steps in any strategy.

- Considering the impact of the economic, technological, or social environment that a firm operates in.

- Matching strategy to the organization’s capabilities and resources.

Putting it together

It is important to remember that the four options in an Ansoff matrix are not mutually exclusive and an organization’s strategy can have elements of all four options.

The below figure summarizes the essence of the Ansoff Matrix:

Sources

- “A Century of America’s Top 10 Companies, in One Chart”. Howmuch.net, https://howmuch.net/articles/100-years-of-americas-top-10-companies. Accessed 27 Feb 2024

- “Igor Ansoff”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Igor_Ansoff. Accessed 27 Feb 2024

- “Strategies For Diversification”. H Igor Ansoff, https://archive.org/details/strategiesfordiversificationansoff1957hbr. Accessed 27 Feb 2024

- “The Ansoff Matrix – GBRW Bank Strategy Guide Series”. GBRW, https://gbrw.com/the-ansoff-matrix-gbrw-bank-strategy-guide-series-1/. Accessed 27 Feb 2024

- “Apple Watch 42mm (1st gen) pictures”. GSM Arena, https://www.gsmarena.com/apple_watch_42mm_(1st_gen)-pictures-7696.php. Accessed 26 Feb 2024

- “The evolution of Apple’s iPhone”. Computer World, https://www.computerworld.com/article/3692531/evolution-of-apple-iphone.html. Accessed 26 Feb 2024

- “Wertkauf”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wertkauf. Accessed 25 Feb 2024

- “Wal-Mart pulls out of Germany”. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2006/jul/28/retail.money. Accessed 25 Feb 2024

- “Athleisure Market Worth $662.56 Billion By 2030 | CAGR: 9.1%”. Grand View Research, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/press-release/global-athleisure-market. Accessed 01 Mar 2024

- “From Competitive Advantage to Corporate Strategy”. Michael E. Porter (Harvard Business Review), https://hbr.org/1987/05/from-competitive-advantage-to-corporate-strategy. Accessed 01 Mar 2024

- “Porter’s Five Forces”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/porters-five-forces/. Accessed 27 Feb 2024

- “Philip Morris to Sell Seven-Up’s U.S. Operations to Dallas Group”. LA Times, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1986-10-04-fi-4239-story.html. Accessed 27 Feb 2024

- “Diversification via Acquisition: Creating Value”. Malcolm S. Salter and Wolf A. Weinhold, https://hbr.org/1978/07/diversification-via-acquisition-creating-value. Accessed 27 Feb 2024

- “Honda – How we move you”. Honda, https://global.honda/en/. Accessed 27 Feb 2024

- “List of assets owned by Berkshire Hathaway”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_assets_owned_by_Berkshire_Hathaway. Accessed 27 Feb 2024

- “What if travelling by plane could be fun? The story of Virgin Atlantic”. Virgin (Richard Branson Blog), https://www.virgin.com/branson-family/richard-branson-blog/what-if-travelling-by-plane-could-be-fun-the-story-of-virgin-atlantic. Accessed 01 Mar 2024

- “Crashing The Soda Wars”. Tedium, https://tedium.co/2021/07/21/richard-branson-virgin-cola-history/. Accessed 01 Mar 2024

- “Overview”. Virgin Group, https://www.virgin.com/about-virgin/virgin-group/overview. Accessed 26 Feb 2024