In the real world, a flywheel is a mechanical contraption, a heavy wheel of a sort that is initially resistant to rotation but gets easier as it gains momentum and builds immense rotational energy. The Flywheel Effect applies this physical phenomenon to the world of business.

The concept was developed by Jim Collins, who set out to discover what made some companies vastly outperform the industry while delivering exceptional results over prolonged periods. The companies that Jim studied had delivered returns of over three times the market average for over 15 years.

Jim’s five-year quest yielded many insights, both surprising and contrary to conventional wisdom and uncovered a framework of ideas for organizations to go from being good to great – one of which is the Flywheel Effect. While this article discusses the Flywheel Effect, other frameworks that Jim uncovered can be found in his book “Good to Great” [1].

What is the Flywheel Effect

The Flywheel Effect does not have a precise definition because it is a metaphor rather than a concept or a framework. It puts together subtle but important forces that play a major role in transforming businesses over long periods.

In the world of mechanics, a flywheel is a massive metal disk mounted on an axle such that it is free to rotate when pushed:

Getting the flywheel to spin initially takes great effort, but as it starts inching forward, rotating almost imperceptibly at first, it begins to spin faster. Given enough time and effort, it builds speed and gains momentum. Eventually, a breakthrough point is crossed where the momentum works in one’s favor, and its heavy weight keeps the motion going.

If one asked, “What was the one big push that caused this thing to go so fast?”, the question would seem absurd. It took thousands of pushes, all of which added together in an overall accumulation of effort applied in a consistent direction. Any single heave, no matter how large, only reflects a small fraction of the entire cumulative effort that went into spinning the flywheel.

This is the essence of the Flywheel Effect which, in the context of the business world, captures how small efforts that companies make add up over time to take them from being just average or good to delivering exceptional results.

Analogous to the mechanical flywheel, business transformations never happen in one swoop. There is no single defining action, no grand program, no one killer innovation, no solitary lucky break, no wrenching revolution. Greatness is achieved by a cumulative process, step by step, action by action, decision by decision, turn by turn as the Flywheel Effect eventually adds up to sustained and spectacular results.

Research has shown that pioneering innovators in a new business arena rarely (less than 10 percent of the time) become the big winners in the end. Studies have failed to identify a systematic correlation between achieving the highest levels of performance and being first in the game.

What truly sets the big winners apart is their ability to turn initial success into a sustained flywheel, even if they started behind the pioneers [3] [4] [5] [6].

Dissecting the Flywheel Effect

A handful of concepts are embedded into the Flywheel Effect, which work together to achieve gradual but extraordinary results:

Momentum

In the Newtonian world, an object at rest tends to stay at rest, and an object in motion tends to continue to be in motion. The faster it moves, the more momentum it carries. Likewise, in the business world, a new initiative or an idea can be hard to start, but once it is set into motion, it is more likely to continue and yield results.

Successful companies know that big wins are great but relatively rare. They focus on starting and taking small steps towards the goal which eventually adds up to great results.

Feedback Loops

The faster the flywheel spins, the easier it is to add incremental speed. Likewise, as business initiatives develop and mature, they provide more feedback and clarity that lead to better adjustments and faster progress.

Compounding

The magical power of compounding, while well understood in investing, also applies to the world of business. Small but continued inputs add up over time to provide impressive output, reinforcing each other and eventually delivering great results.

Auto Catalysis

Given enough time, the Flywheel Effect creates a situation where the output of a reaction becomes its catalyst.

For instance, Tesla’s early commitment to electric vehicles (EVs) challenged the prevailing notion of their viability and cost-effectiveness. By disproving this assumption, Tesla not only established the feasibility of EVs but also built an extensive EV ecosystem. As more players enter the EV space, Tesla stands to benefit from the declining cost of batteries and other components – a direct outcome of its consistent efforts.

Direction

Focused efforts are required to build momentum and exploit the returns that compounding brings. Companies that have built successful flywheels have demonstrated years of patience and an unrelenting focus on their goal to achieve results. In contrast, there are several examples of failed businesses where direction and focus shifted with changing leadership till, eventually, they were rendered irrelevant.

How the Flywheel effect works

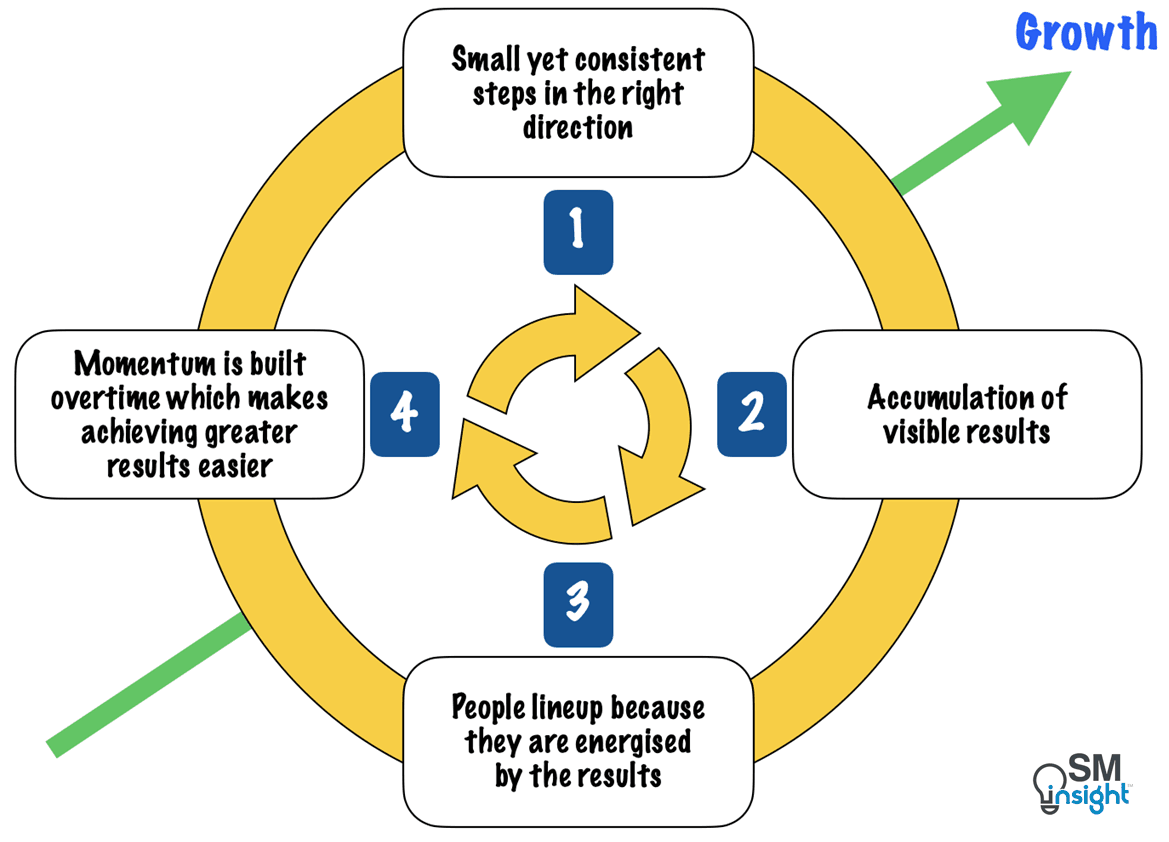

Harnessing the power Flywheel Effect is about understanding a simple truth – tremendous

power exists in continued improvement and the delivery of results.

It is about realizing that tangible accomplishments, no matter how incremental at first, when fit into the context of an overall concept will work. Once it does, people see and feel the buildup of momentum and line up with enthusiasm. Momentum builds over time and a self-reinforcing cycle of result-driven improvements continue.

With the Flywheel Effect working in their favor, executives don’t even realize when their companies cross a significant milestone or achieve a breakthrough. Some of their greatest transformations happen slowly and silently. The Flywheel Effect creates the right conditions where alignment is automatically created across the organization; people voluntarily commit to the new vision and embrace change.

This was evident when Jim Collins interviewed leaders from companies that grew several times the market average, companies such as Abbott Laboratories (3.98 times the market), Fannie Mae (7.56 times the market), Kimberly-Clark Corp.(3.42 times the market), Nucor Corp. (5.16 times the market), and Wells Fargo (3.99 times the market). [7]

Building the Flywheel

Organizations can capture their flywheel using the following steps:

- Create a list of significant, replicable successes that the organization has achieved. This should include new initiatives and offerings that far exceeded expectations.

- Compile a list of failures and disappointments – those that failed outright or fell far below expectations.

- Compare the successes with the failures and ask: “What do successes and failures say about the possible components of the organization’s flywheel?”

- Identify four to six components and sketch the flywheel.

Try to answer:- Where does the flywheel start—what’s the top of the loop?

- What follows next? And next after that?

- Try to explain why each component must follow the previous one. Does it seem logical?

Continue questioning and outline the path back to the top of the loop. It is important to explain how the identified loop cycles back upon itself to accelerate momentum. - To avoid making the flywheel too complicated, it is important to restrict the number of components to not more than six. Consolidating and capturing the essence in a simple-to-understand form is important.

- The flywheel must then be tested and tweaked until it explains the previously identified successes and failures. In short, the flywheel must validate the organization’s empirical experience.

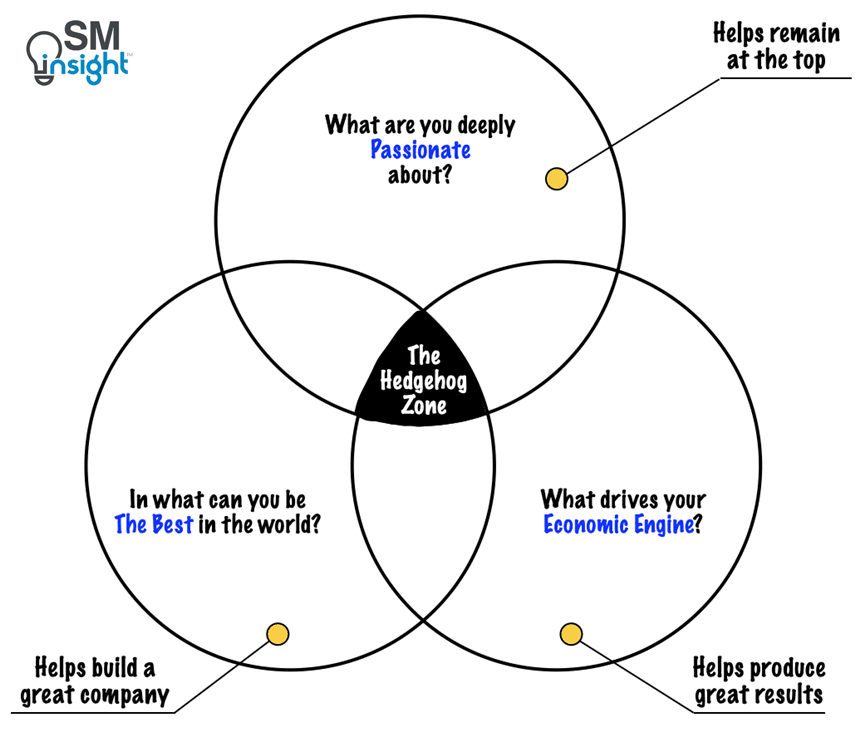

- Check if the flywheel is consistent with the organization’s Hedgehog Concept, which flows from deeply understanding the intersection of the following three circles:

The Hedgehog Zone is where companies should ideally operate their business.

The Hedgehog Zone is where companies should ideally operate their business. - The flywheel must fit with what the organization is deeply passionate about – its core guiding purpose and enduring values. It must build upon what the organization sees itself to be the best in the world at, and it must fuel the organization’s economic and resource engine.

Once the flywheel is built, the question shifts to “What do we need to do better to accelerate momentum?”

The power of the flywheel effect depends upon two things: getting the sequence right and every component performing to its fullest. One simply cannot falter on any of the identified components.

To explain this further, suppose an organization’s flywheel had six components and the performance of each on a scale of 1 to 10 was rated to be 9, 10, 8, 3, 9, and 10. In such a scenario, the overall performance would be limited by the component scoring 3. The flywheel would gain momentum only when this weakest link would improve.

Sustaining the momentum is not about focusing on one component “OR” the other. It is about making “ALL” of them work together to their fullest potential.

A properly conceived and well-executed flywheel brings continuity and propels change as it demands continuous improvements to every component. To reap the benefits, however, an organization must stay with its flywheel long enough to get its full compounding effect.

Borrowing a Flywheel

Organizations without the components of a flywheel already in place, such as early-stage entrepreneurial companies can jump-start the process by importing insights from flywheels that others have built.

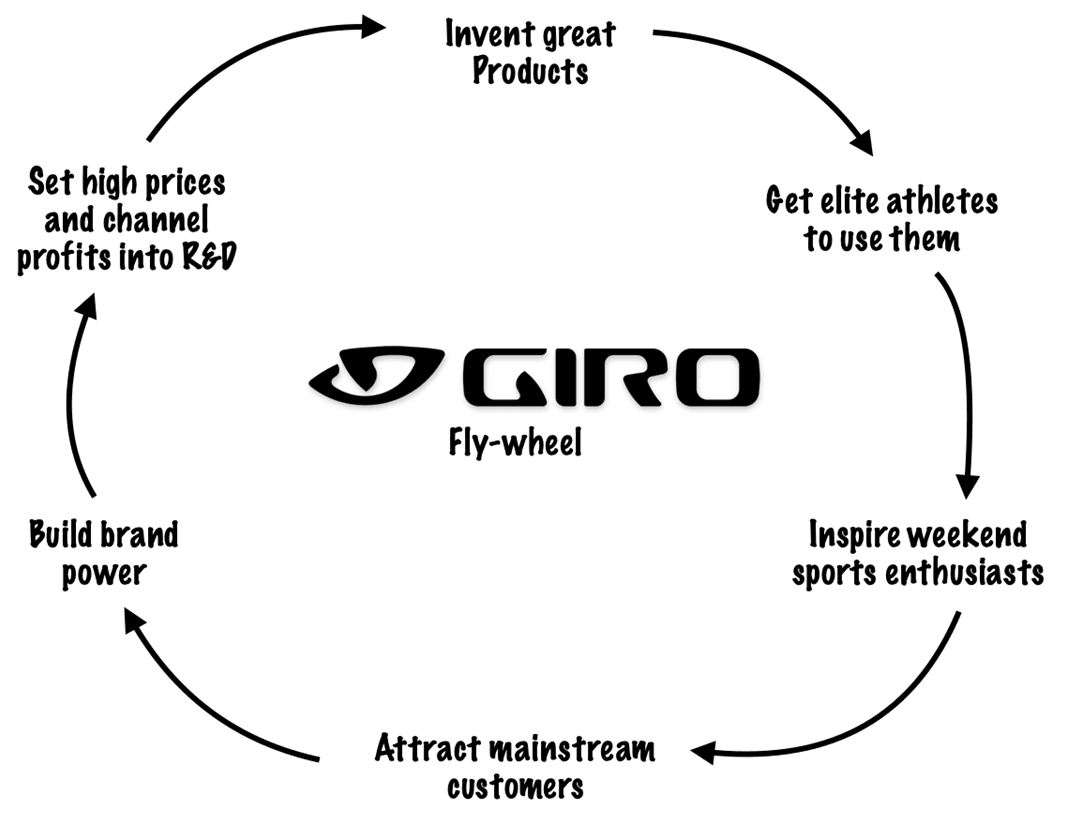

For example, when Jim Gentes [8] founded Giro Sports Design [9], an American manufacturer of snow and cycling helmets, he managed to build a sustained flywheel that “spins” even today. He achieved this when Giro was just a garage start-up and had only a newly designed bicycle helmet to offer.

By studying Nike, Gentes gleaned an essential insight – the hierarchy of social influence for athletic gear. He understood that if a Tour de France winner were to wear a brand’s helmet, serious nonprofessional cyclists would want to wear that helmet, which then would trigger the cascade of influence and build the brand.

He validated this insight by betting the company’s resources on sponsoring elite American cyclist Greg LeMond to wear a Giro helmet during the 1989 Tour de France. LeMond won the event and Giro went on to become the preferred choice for serious riders.

Adopting a key insight from Nike’s flywheel and blending it with its passion for inventing great new products, Gentes propelled Giro far beyond the garage into a multi-million-dollar brand.

Extending the flywheel

No matter how good a company is at crystalizing the components of its flywheel and making it spin to its advantage, eventually, there comes a point where changes are required.

A historical look at great companies reveals a frequent pattern – such companies begin by being successful in a specific business arena and make the most of their early big bets. Once successful, they then make a conceptual shift from “running a business” to turning their flywheel. Over time, they extend that flywheel to test new areas that might work and use it as a hedge against uncertainty.

In all this process, the underlying construct of the flywheel remains the same, though products or markets may change. In short, the momentum is not lost but transferred from one arena to another.

For example, in 2002, when Apple introduced the iPod, nearly all of its flywheel momentum was generated by its line of Macintosh personal computers. iPod generated less than 3 per cent of Apple’s sales at the time. However, Apple kept improvising the iPod, even developing an online music store (iTunes) along the way.

By 2006, the iPod overtook Macintosh as Apple’s largest source of revenue. Eventually, Apple combined the iPod, iTunes, and communication into a single smart device, the iPhone which almost single-handedly managed to make Apple the most profitable and most valuable company of all time [11].

Intel achieved something similar when it made the leap from memory chips to processing chips which is discussed in more detail in the example section at the end of this article.

In corporate history, there are several examples of companies that have extended and accelerated an underlying flywheel that had been turning for years:

| Company | First Arena of Flywheel Success | Next Big Extension of the Flywheel |

|---|---|---|

| 3M | Abrasives (e.g., sandpaper) | Adhesives (e.g., Scotch Tape) |

| Amazon | Internet-enabled retail for consumers | Cloud-enabled enterprises web services |

| Amgen | Therapeutics for low-blood-cell conditions | Therapeutics for inflammation and cancer |

| Boeing | Military aircraft | Commercial jetliners |

| IBM | Accounting tabulating machines | Computers |

| Johnson & Johnson | Medical and surgical products | Consumer health-care products |

| Kroger | Small-scale grocery stores | Large-scale superstores |

| Marriott | Restaurants | Hotels |

| Merck | Chemicals | Pharmaceuticals |

| Microsoft | Computer languages | Operating systems and applications |

| Nordstrom | Shoe stores | Department stores |

| Nucor | Steel joists | Manufactured steel |

| Progressive | Non-standard (high-risk) car insurance | Standard car insurance |

| Southwest Airlines | Low-cost intrastate airline (Texas only) | Low-cost interstate airline (coast to coast) |

| Stryker | Hospital beds | Surgical products |

| Walt Disney | Animated films | Theme parks |

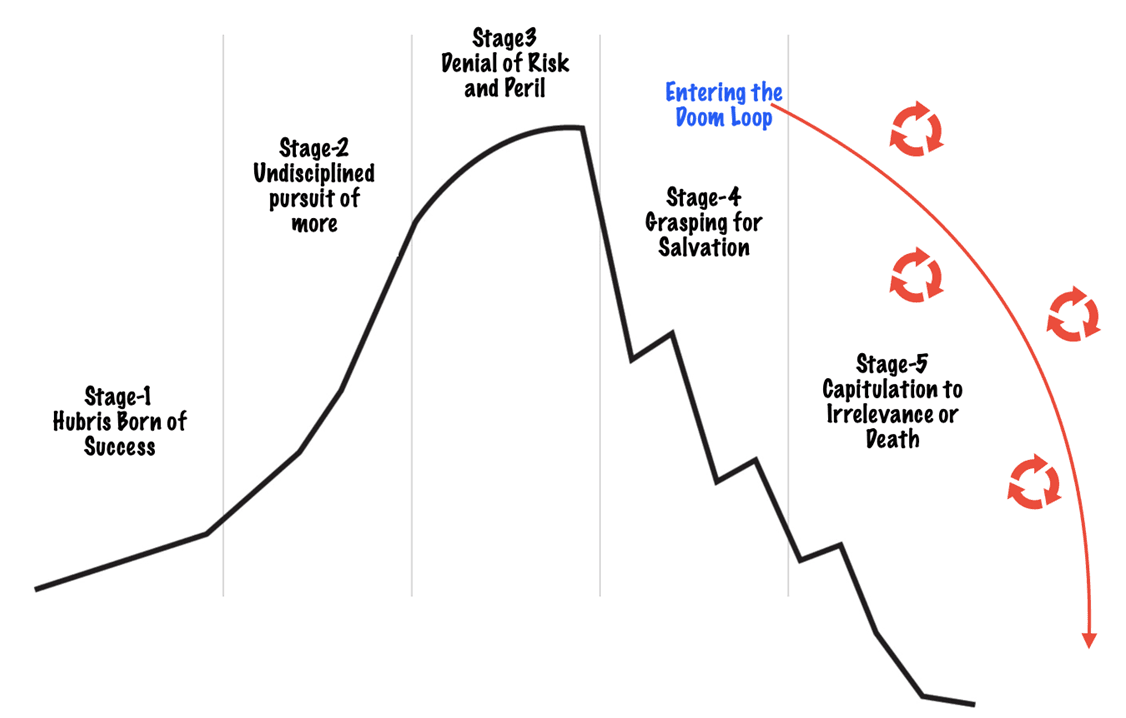

Avoiding the Doom Loop

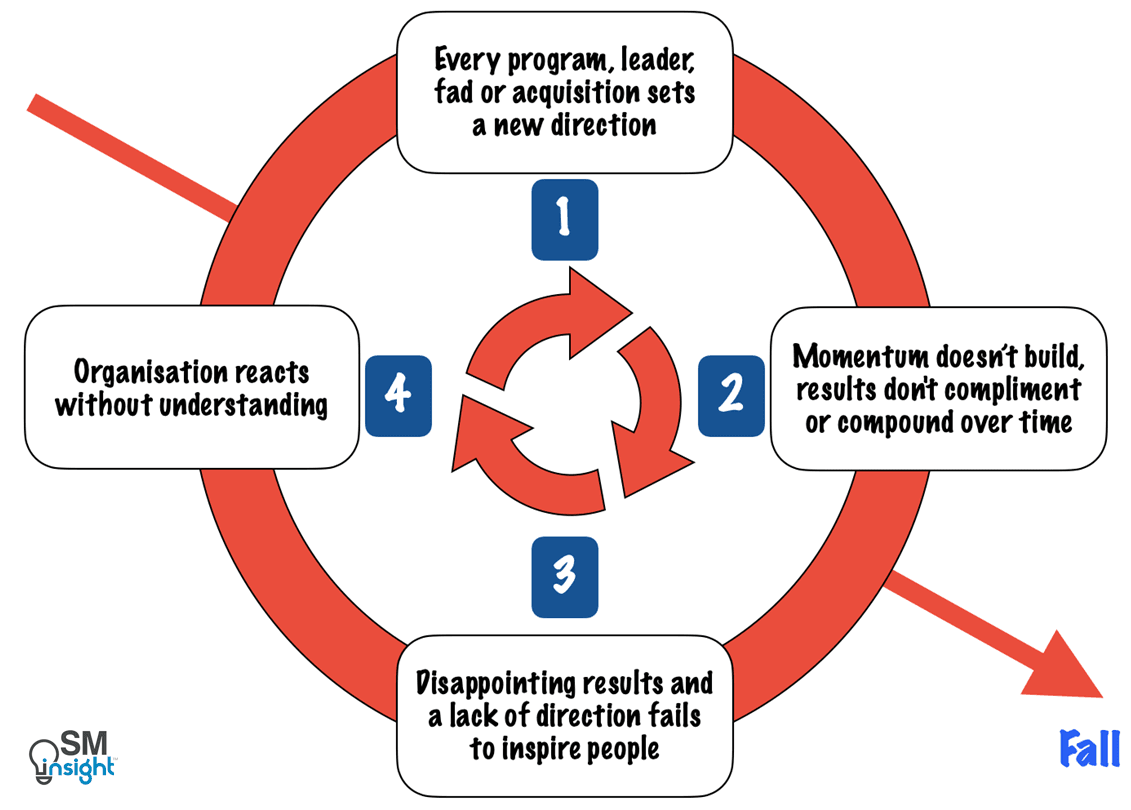

On the other end of the spectrum are companies that are on the hunt for that single defining moment or a great product that could change their course. They channel their energy into launching programs with great fanfare to motivate people only to see that such programs fail to produce sustained results.

They are on a constant lookout for the next grand program, the one killer innovation, the miracle moment that would allow them to skip the arduous buildup stage and jump right to the breakthrough.

Unfortunately, what such companies essentially do is push their flywheel in one direction, then stop, change course, and throw it in a new direction. After years of lurching back and forth, and fail to build sustained momentum, and eventually fall into the doom loop:

Even great companies can spiral into the doom loop. It is a slow process, but with a powerful influence that usually happens in five stages:

When great companies abandon the key principles that made them great in the first place, they inevitably head towards their downfall. Such companies vest power in the hands of the wrong leaders, veer away from who they are and pay little attention to getting the right people on the bus. They fail to confront the brutal facts and stray far beyond their Hedgehog Zone. Eventually, they corrupt their core values and lose their purpose.

There are several traits that a company exhibits, based on which it is possible to identify if the company is leveraging the Flywheel Effect or is heading toward the Doom Loop:

| Those who exploit the Flywheel Effect | Those that have fallen into the Doom Loop |

|---|---|

| Follow a pattern of building sound foundations that eventually lead to a breakthrough. | Skip the foundation building and focus only on the breakthrough. |

| Follow an organic process where breakthrough is reached through accumulation of steps, one after the other, turn by turn of the flywheel. | Announce big programs, radical change efforts, dramatic revolutions, and chronic restructuring. Always on the lookout for the next miracle moment or a new savior. |

| Confront brutal facts to see clearly what steps must be taken to build momentum. | Embrace fads to avoid facing the brutal facts. |

| Maintain consistency and clear focus. | Characterized by chronic inconsistency, straying back and forth while not maintaining focus. |

| Emphasize on getting the right people onboard, have disciplined approach thoughts and actions. | Jump into action with little thought to people’s skills and capabilities. |

| Leverage technology that aligns with the organization’s momentum. | Chase technology with a fear of being left behind, even at the cost of disturbing gained momentum. |

| Build the flywheel, get it spinning and make only those acquisitions that align with the organization. | Acquisitions are made irrespective of alignment or the fact that it could kill the organization’s momentum. |

| People do not need to be motivated or aligned. Results take care of these factors. | A lot of energy is spent motivating and aligning people, rallying them around changing visions. |

| Results speak for themselves and need little selling. | Need to “sell” better future results to compensate for a lack of performance in the present. |

| There is consistency over time. Each leader or generation builds on the achievements of the previous. The flywheel spins faster with time. | Each leader brings his own views and takes a radically new path. Momentum is lost and the organization enters the doom loop. |

Examples of Flywheel Effect

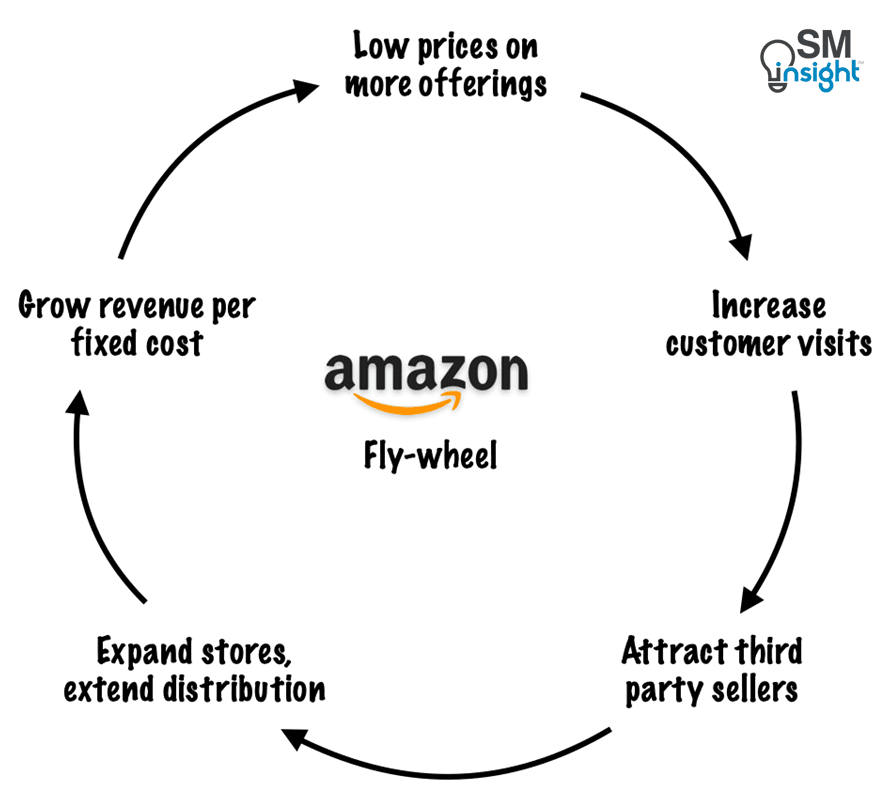

Amazon

Amazon grabbed onto the flywheel concept and deployed it to articulate a momentum machine centered around its key goal of delivering value to its customers:

By offering the best prices, Amazon attracted more customers. More customers increased the volume of sales and attracted more commission-paying third-party sellers to the site. This in turn allowed Amazon to get more out of fixed costs like fulfillment centers and servers needed to run their IT infrastructure. This increased efficiency which enabled Amazon to further lower prices.

Amazon’s actions were led by the reasoning that every action must accelerate the flywheel in one way or the other – eventually building tremendous momentum and transforming it into the behemoth we know today.

While Amazon operates in several sectors, its underlying flywheel remains the same. Each component works to maximize value to its customers.

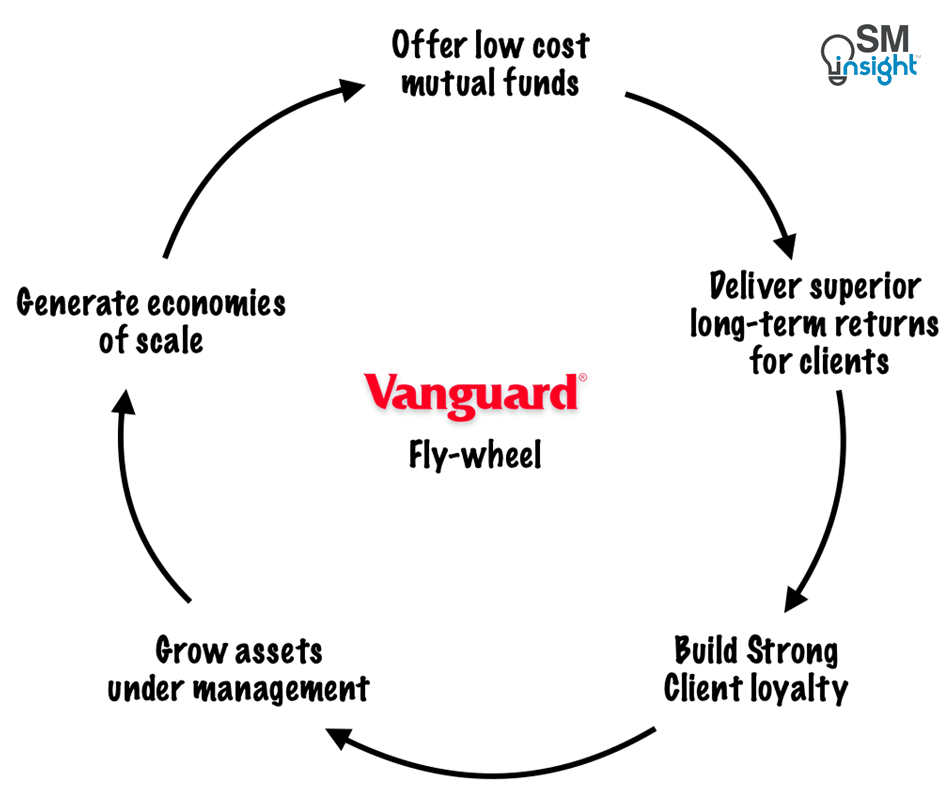

Vanguard

The Vanguard Group is an American investment advisor with over $7 trillion in global assets under management. It is also the largest provider of mutual funds and the second-largest provider of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) in the world.

It can be seen from Vanguard’s simplified flywheel how each component isn’t merely a next action step on a list but almost an inevitable consequence of the step that came before.

Vanguard’s lower-cost mutual funds almost always deliver superior long-term returns to investors when compared to higher-cost funds that invest in the same assets. Superior returns help build client loyalty which drives growth in the assets under management. This generates economies of scale that help lower the costs.

Vanguard had been turning some form of this flywheel for decades, building upon new insights and principles since it championed the world’s first index mutual funds.

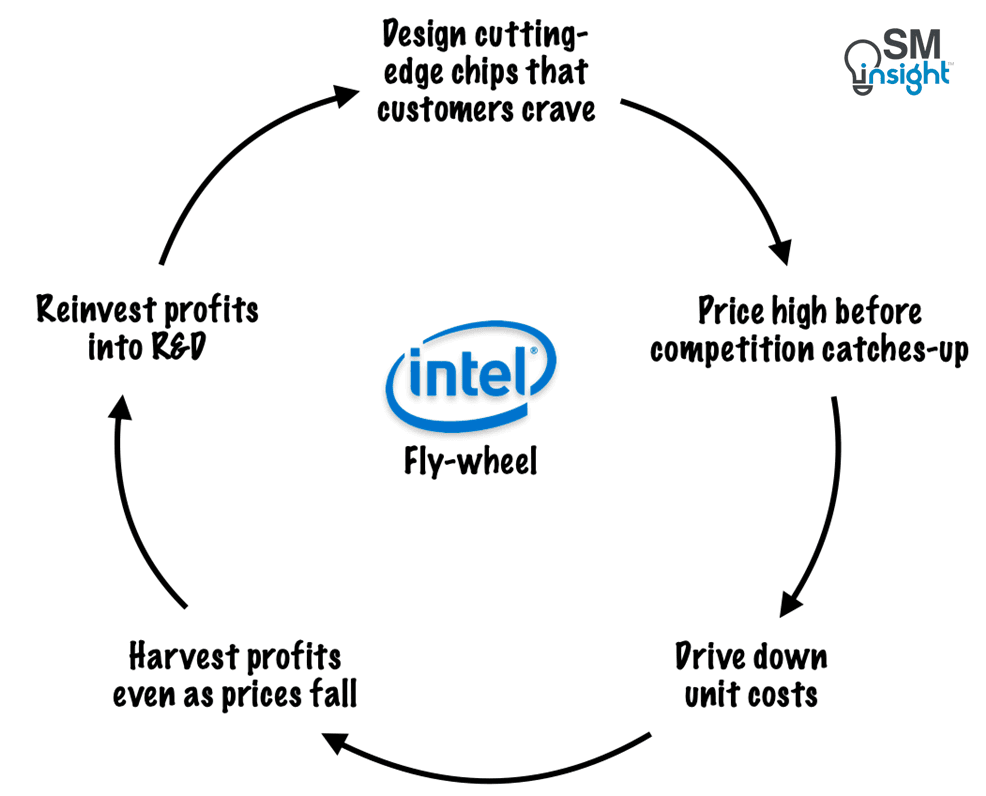

Intel – same flywheel, different products

When Intel opened shop, memory chips (chips that store data) were its main offerings, unlike the processor chips that the company is known for today. Intel built a flywheel around harnessing the power of Moore’s Law [12]:

microprocessing chips

Intel’s founding team created a strategic compounding machine:

- Design new chips that customers crave.

- Price high before the competition catches up.

- Drive down unit costs as volume increases (due to economies of scale).

- Harvest high profits even as competition drives down prices.

- Reinvest those profits into R&D to design the next generation of chips.

This flywheel powered Intel’s rise from start-up to a great company in the memory-chip business. However, by the mid-1980s, a brutal international price war killed sales and evaporated the company’s profits. It was clear that Intel had to get out of the memory business – its bread-and-butter product. And Intel did get out of memories.

But did Intel jettison its flywheel? No!

Intel had been building up a side business in microprocessor chips for more than a decade. Most importantly, the move did not disturb the underlying flywheel architecture which could apply just as soundly to microprocessor chips as memory chips. In short, it was a case of different chips but very much the same underlying flywheel.

What Intel achieved was a transfer of momentum from the memory business to the microprocessor business – not a jagged break to create an entirely new flywheel. If Intel had tossed out its underlying flywheel architecture when it exited memories, it probably wouldn’t have become the dominant chip maker that powered the personal computer revolution.

Amazon, Vanguard, and Intel – each operating in a highly turbulent industry show how success is less about any specific line of business, product, idea, or invention and more about the underlying flywheel architecture and how well it is conceived and followed.

This flywheel effect has been observed across diverse domains, spanning from social movements and sports to entertainment industries such as movies and music, as well as successful election campaigns and military campaigns. Even accomplished long-term investors and philanthropists have leveraged the power of the flywheel.

A closer look at every enduring enterprise will typically reveal the presence of a flywheel mechanism, though it might be hard to see at first.

When companies get their flywheel right, it guides and drives momentum for a long time. And when situations change, the flywheel can be repurposed to reflect the new realities without losing built-up momentum.

Sources

1. “Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap and Others Don’t”. Jim Collins, https://www.amazon.com/Good-Great-Some-Companies-Others/dp/0066620996. Accessed 19 Sep 2024.

2. “Corliss steam engine”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corliss_steam_engine. Accessed 19 Sep 2024.

3. “Will and Vision: How Latecomers Grow to Dominate Markets”. Gerard J. Tellis, https://www.amazon.com/Will-Vision-Latecomers-Dominate-Markets/dp/1932800255. Accessed 19 Sep 2024.

4. “Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies”. Jim Collins and Jerry Porras, https://www.amazon.com/Built-Last-Successful-Visionary-Essentials/dp/0060516402. Accessed 19 Sep 2024.

5. “How The Mighty Fall: And Why Some Companies Never Give In”. Jim Collins, https://www.amazon.com/How-Mighty-Fall-Companies-Never/dp/0977326411. Accessed 18 Sep 2024.

6. “Great by Choice: Uncertainty, Chaos, and Luck–Why Some Thrive Despite Them All”. Jim Collins and Morten Hansen, https://www.amazon.com/Great-Choice-Uncertainty-Luck-Why-Despite/dp/0062120999. Accessed 18 Sep 2024.

7. “Good to Great”. FastCompany, https://www.fastcompany.com/43811/good-great. Accessed 20 Sep 2024.

8. “Head & heart: The helmet that changed everything”. Outsideonline, https://velo.outsideonline.com/road/road-culture/head-heart-giros-long-commitment-to-innovation/. Accessed 20 Sep 2024.

9. “The Giro Story”. Giro Sports Design, https://www.giro.com/the-giro-story.html. Accessed 20 Sep 2024.

10. “Turning the Flywheel: A Monograph to Accompany Good to Great (Good to Great, 6)”. Jim Collins, https://www.amazon.com/Turning-Flywheel-Monograph-Accompany-Great/dp/0062933795/. Accessed 20 Sep 2024.

11. “Apple’s Incredible 21st Century Growth”. Statista, https://www.statista.com/chart/27345/apple-revenue-by-segment/. Accessed 21 Sep 2024.

12. “Moore’s law”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moore%27s_law. Accessed 21 Sep 2024.

The Hedgehog Zone is where companies should ideally operate their business.

The Hedgehog Zone is where companies should ideally operate their business.

Great Concept, using the same strategy but never knew it was FLY WHEEL effect.