What is The Pygmalion Effect

The Pygmalion effect is based on the notion that the way one person treats another can, for better or worse, be transforming. It is a psychological phenomenon in which high expectations lead to improved performance in a given area and low expectations lead to worse.

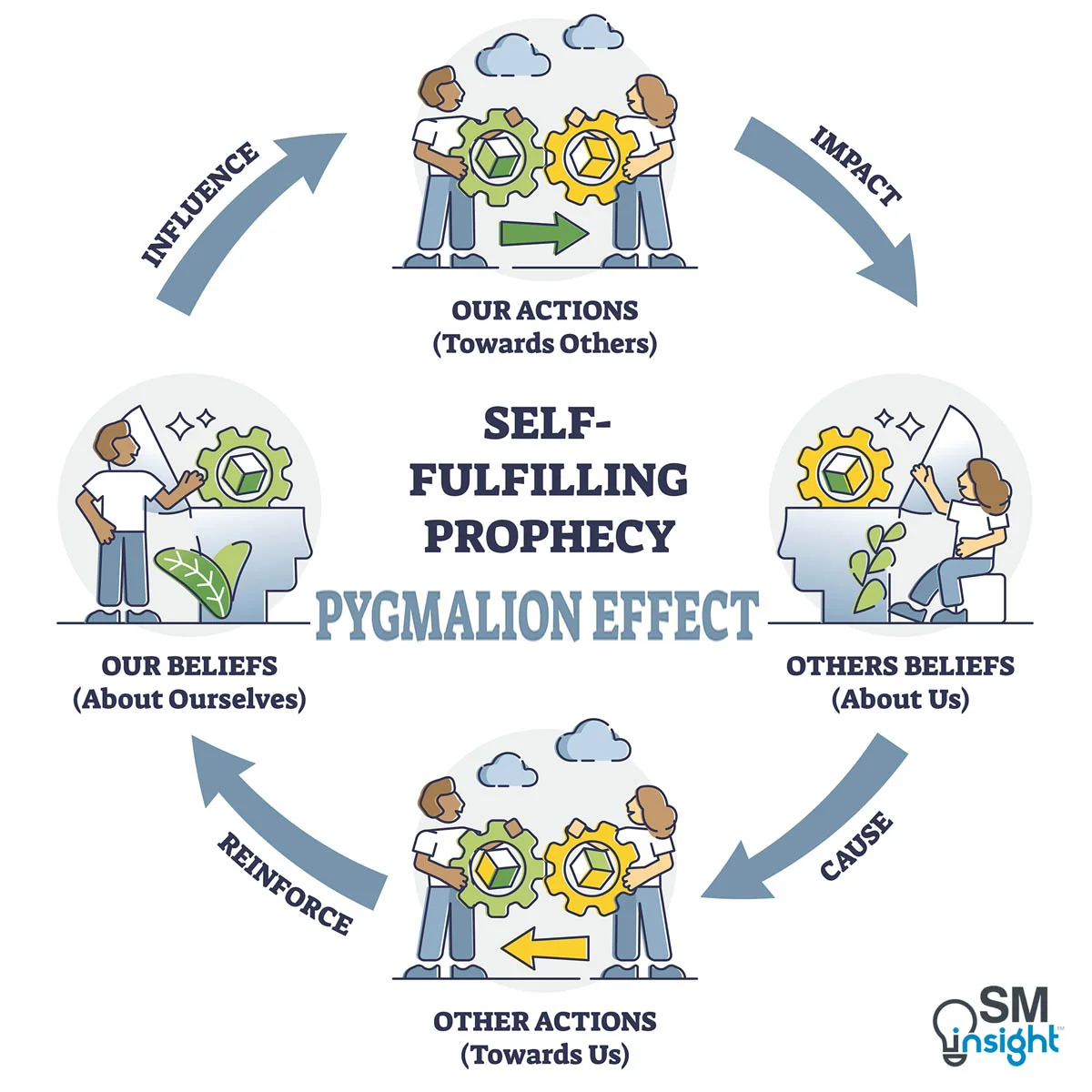

The Pygmalion effect can be best understood from the figure below:

The Pygmalion effect has its influence in a diverse set of fields ranging from education to management to the military. Psychological nursing interventions based on the effect were even found to alleviate the negative emotions of patients suspected of COVID-19.[1]

Pygmalion in the Office

Consider the following example in a corporate setting:

In a fast-paced tech company, a manager named Alex believes that one of his team members, Sarah, has the potential to become a future leader. Alex assigns Sarah to lead a high-impact project, providing her with resources, mentorship, and opportunities for skill development.

Sarah, sensing Alex’s confidence in her abilities, embraces the challenge and works tirelessly to meet and exceed expectations. As the project progresses, Sarah’s leadership and decision-making abilities shine through, resulting in the project’s success.

This outcome reinforces Alex’s original belief in Sarah’s potential, leading him to assign her even more responsibilities and involve her in strategic discussions.

Sarah’s increased exposure and recognition within the company boost her confidence and drive her to further excel. With each accomplishment, Sarah’s reputation as a capable and talented professional grows.

Colleagues and higher-ups take notice of her contributions, opening doors to new opportunities and collaborations. As Sarah continues to thrive, her self-assurance and motivation continue to rise, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of achievement.

This is the Pygmalion Effect at work in a professional setup and reveals how Alex’s elevated expectations set a positive feedback loop in motion. Sara’s improved performance validates her belief, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy.

This process demonstrates the significant impact of a manager’s perceptions and encouragement on an employee’s development and accomplishments.

Origin of the Pygmalion Effect

In the 1960s, a classic experiment by Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobsen first provided evidence for the Pygmalion effect. Findings from their experiment (and other subsequent explorations) showed that teacher expectations of students influenced student performance more than any differences in talent or intelligence.[2]

The experiment was conducted at a public elementary school, where they chose a group of children at random and told teachers that these students had taken the Harvard Test of Inflected Acquisition and were identified as “growth-spurters.”

Teachers were explained that these children had great potential and would likely experience a great deal of intellectual growth within the next year.

When the data on all the students were compared, these randomly chosen “growth-spurters”, students whom the teachers expected to do well, did exceedingly well.

Since the children were not told of their false test of inflected acquisition results, the only explanation for these outcomes was that the teachers’ expectations influenced student performance, i.e., the Pygmalion effect at work.

In Rosenthal’s words, the Pygmalion effect is defined as:

The effect is named after the Greek myth of Pygmalion, the sculptor who fell so much in love with the perfectly beautiful statue he created that the statue came to life.[4]

Pygmalion’s opposite effect is the Golem Effect[5], in which low expectations are communicated and self-efficacy and performance decrease as a result.

A Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

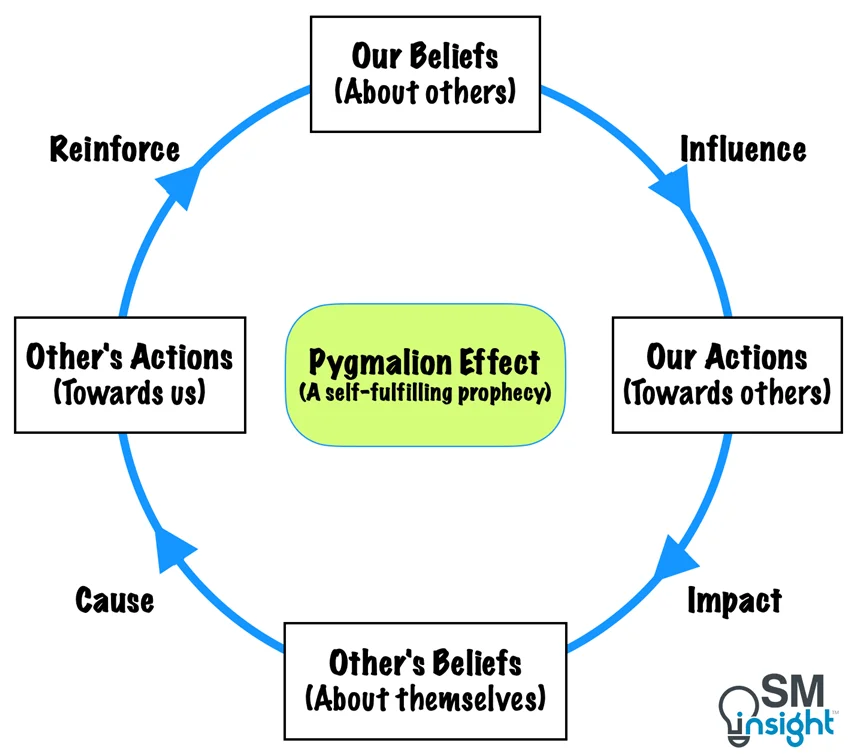

The Pygmalion Effect is a form of Self-Fulfilling Prophecy, a prediction that becomes true merely because the prediction exists.

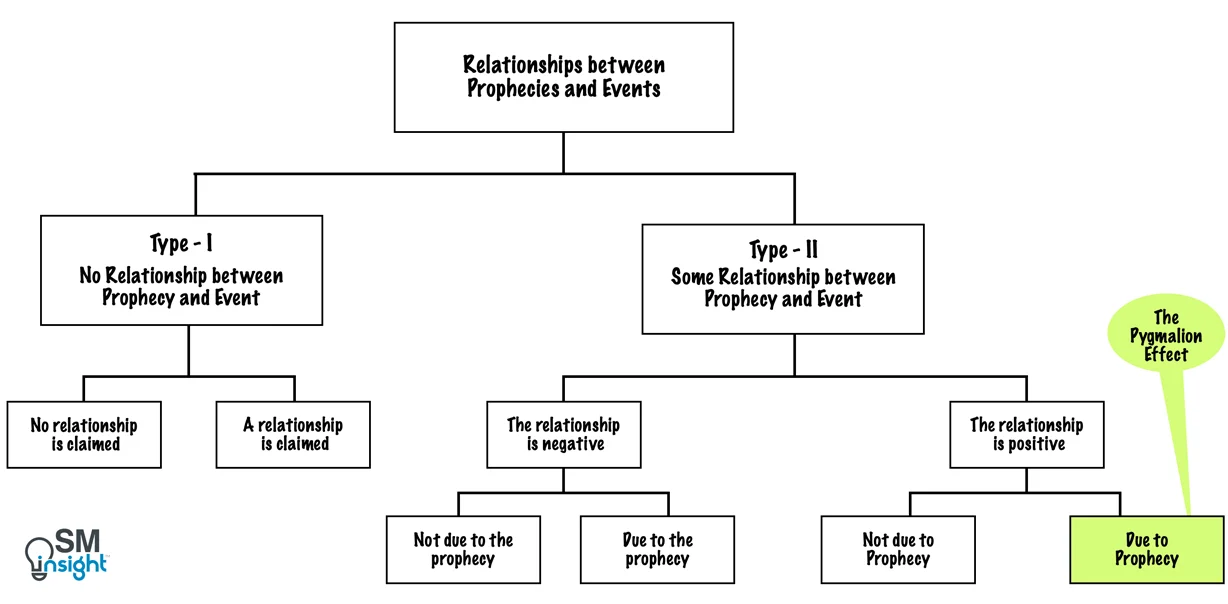

People make prophecies about future events or hold expectancies about them. Many possible relationships exist between prophecies of events and the events as they subsequently occur.

The Pygmalion Effect falls under the self-fulfilling prophecy as shown below:

Role of Pygmalion in Management

While the powerful influence of one person’s expectations on another’s behavior has long been recognized by physicians, behavioral scientists, and teachers, it plays an equally dominant role in organizations.

Managers’ expectations for individuals as well as groups have been proven to strongly influence the results. Various case studies and scientific research reveal the following[7]:

- What managers expect of subordinates and the way they treat them largely determines their performance and career progress.

- A unique characteristic of superior managers is the ability to create high-performance expectations that subordinates fulfill.

- Less effective managers fail to develop similar expectations, and therefore, the productivity of their subordinates suffers.

- Subordinates, more often than not, appear to do what they believe they are expected to do.

Impact of Manager’s Beliefs on Productivity

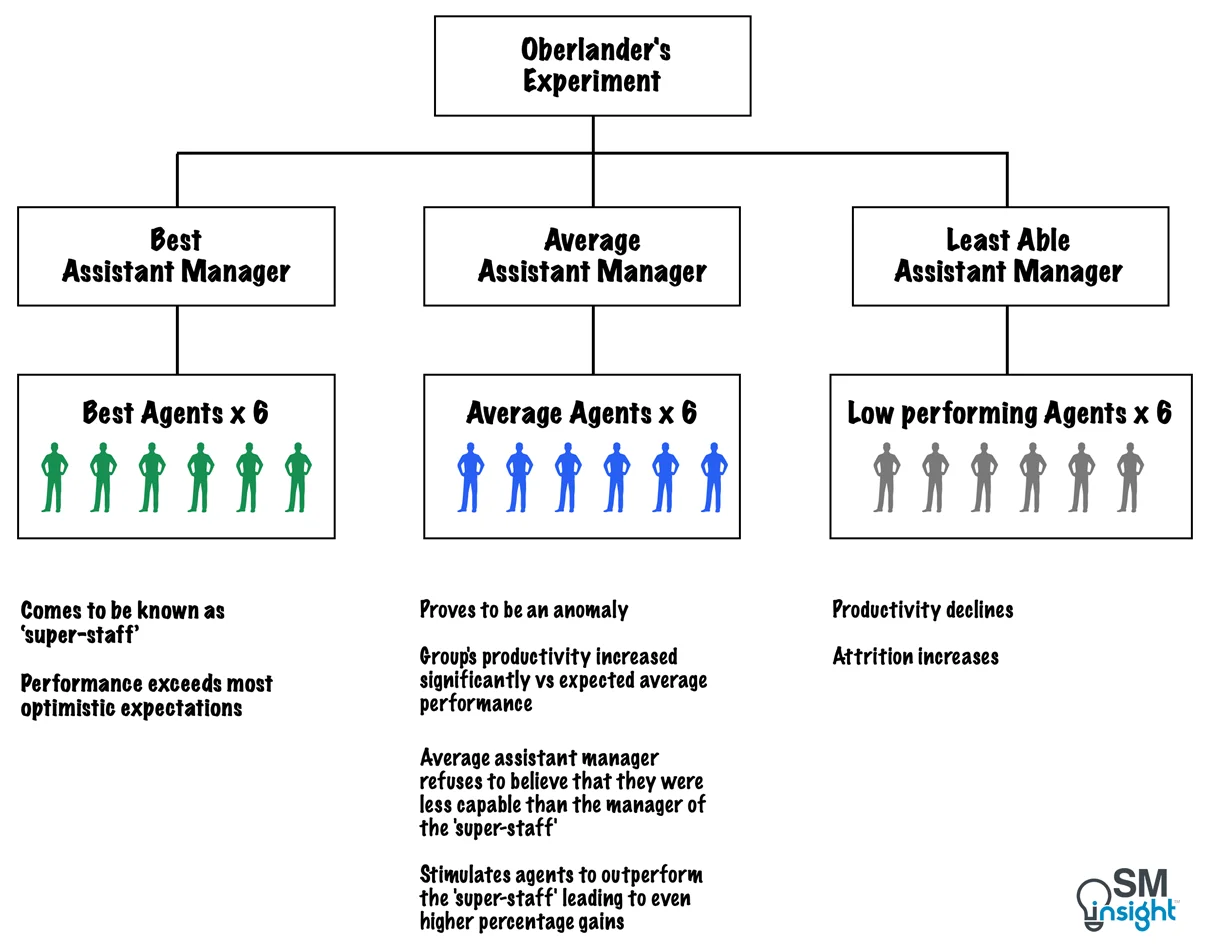

In 1961, Alfred Oberlander, manager at Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, conducted an organizational experiment to explore how managerial expectations impact productivity.

Noticing that exceptional insurance agencies grew faster, and new agents (irrespective of their differing abilities) did better in those agencies, Oberlander formed three distinct groups: a “super-staff” of top agents under his best managers, a second group of average agents under an average manager and a third group of low performers as shown:

He challenged his best performers (known as super-staff) to achieve two-thirds of the previous year’s premium volume which yielded remarkable results and a 40% improvement in overall agency performance.

The super-staff continued to excel, while the low-performer group’s productivity continued to decline as anticipated.

Surprisingly, though, the “average” group outperformed expectations due to the assistant manager’s belief in their team’s potential and the efforts to motivate them. This middle group consistently increased productivity (more than the super-staff with respect to expectations), driven by the manager’s positive influence.

The experiment showed how the self-perception of the average manager was pivotal in influencing agents, fostering high expectations and increasing productivity.

Due to the Pygmalion effect, managerial beliefs can create strong self-fulfilling prophecies that could make or break team performance.

Role in Failure

Studies have shown how unsuccessful salespersons have great difficulty in maintaining their self-image and self-esteem. In response to low managerial expectations, they typically attempt to prevent additional damage to their egos by avoiding situations that might lead to greater failure.[6]

Such salespersons are known to either reduce the number of sales calls they make or avoid trying to close sales when that might result in further painful rejection or both.

Low expectations and damaged egos lead them to behave in a manner that increases the probability of failure, thereby fulfilling their managers’ expectations.[7]

Communicating expectations

If managers believe subordinates will perform poorly, it is virtually impossible for them to mask their expectations because the message is usually communicated unintentionally, without conscious action on their part.

For example, saying nothing becomes cold and uncommunicative and is usually taken as a sign that they are displeased by a subordinate or believe that he or she is hopeless.

Communication of expectations is often more about how one behaves rather than what one says. Indifferent and noncommittal treatment, more often than not, is the kind of treatment that communicates low expectations and leads to poor performance.

Managers are more effective in communicating low expectations to their subordinates than in communicating high expectations, even though most managers believe the opposite. It is astonishingly difficult to recognize the clarity with which negative feelings are transmitted while on the other hand, it is equally difficult to communicate positive feelings.

Often, the way managers treat subordinates, not the way they organize them, is the key to high expectations and high productivity.

Test of Reality

Expectations must pass the test of reality before they can be translated into performance. Teams and individuals will not be motivated to reach high levels of productivity unless they consider the boss’s high expectations realistic and achievable. Striving for unattainable goals eventually leads to giving up on trying and instead settling for lower standards.

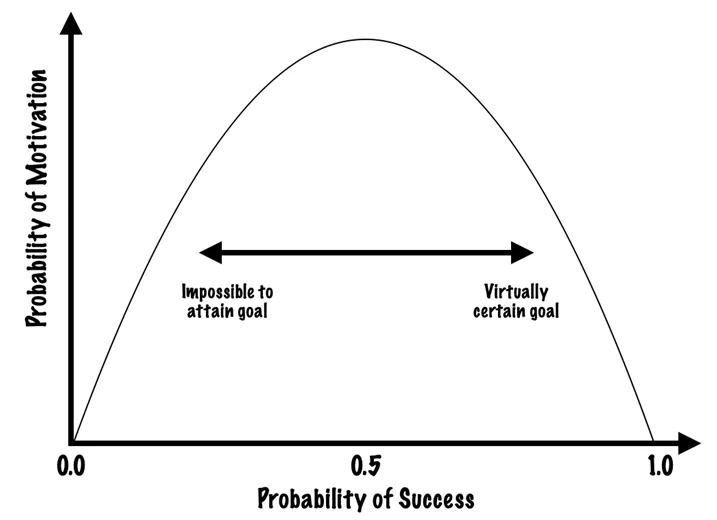

Research by David C. McClelland of Harvard University and John W. Atkinson of the University of Michigan[7] has demonstrated that the relationship of motivation to expectancy varies in the form of a bell-shaped curve as shown:

Notice how no motivation or response is aroused when the goal is perceived as being either virtually certain or virtually impossible to attain.

The degree of motivation and effort rises until the expectancy of success reaches 50%, then begins to fall even though the expectancy of success continues to increase.

When subordinates fail to meet performance expectations that are close to their own level of aspirations, they will lower personal performance goals and standards, and performance will tend to drop off, leading to negativity towards the job. This then leads to high levels of attrition.

The Difference Between a Superior and a Weak Manager

Superior managers are consistently able to create high-performance expectations that their subordinates fulfill while others find this hard to replicate.

The secret lies in superior managers having greater confidence in their own ability to develop the talents of their subordinates (ability to select, train, and motivate their subordinates).

What managers believe about themselves subtly influences what they believe about their subordinates, what they expect of them, and how they treat them.

Also, the superior managers’ record of success and confidence in their own ability give their high expectations credibility. Consequently, their subordinates accept these expectations as realistic and try hard to achieve them.

The importance of what a manager believes about his/her training and motivational ability is illustrated by “Sweeney’s Miracle”[9], a managerial and educational self-fulfilling prophecy:

Dr James Sweeney, a Tulane University professor, lacked concrete evidence for his human potential theories until he met George Johnson, who was hired as the janitor for the bio-medical computer center, which Sweeney was also in charge of.

Though Johnson had a limited educational background, Sweeney’s conviction led him to work with him, focusing on making him a computer operator. After six months of effort, Johnson transformed into a successful programmer and top computer expert.

Johnson’s progress showcased the power of positive expectancy and mentoring. He eventually became Director of Data Processing Operations at Pan American Life Insurance Company, highlighting the impact of belief and commitment in unlocking potential.

The story exemplifies the influence of positive expectancy in driving personal growth and achievement.

Early Years Are Key to Future Performance

Managerial expectations have the most influence on young people. As subordinates mature and gain experience, their self-image gradually hardens, and they begin to see themselves as their career records imply and the “reality” of their past performance takes over.

This is demonstrated in Rosenthal’s experiments[6] with education, where the teachers’ expectations are more effective in influencing intellectual growth in younger children than in older children.

In the lower grades (particularly the first and second grades), the effects of teachers’ expectations were dramatic. In the upper-grade levels, teachers’ prophecies seemed to have little effect on children’s intellectual growth, although they did affect motivation and attitude.

The early years in a business organization are when young people can be strongly influenced by managerial expectations. This then becomes critical in determining future performance and career progress.

In a business setup, this phenomenon was studied by Berlew and Hall at AT&T, who concluded that the correlation between how much a company expects of an employee in the first year and how much that employee contributes during the next five years was “too compelling to be ignored”.[10]

Meeting high company expectations in the critical first year leads to the internalization of positive job attitudes and high standards; these attitudes and standards, in turn, first lead to and then are reinforced by strong performance and success in later years.

The first year is a critical period for learning, a time when a trainee is uniquely ready to develop or change in the direction of the company’s expectations.

The First Manager is the Most Influential Manager

During the “Malleable” of a young employee, if managers are unable/unwilling to develop the skills in young employees, they will set lower personal standards, their self-images will be impaired, and they will develop negative attitudes toward jobs, employers, and their own careers in business.

Since the chances of building successful careers with these first employers will decline rapidly, the employees will leave in the hope of finding better opportunities.

Conversely, if early managers help employees achieve maximum potential, they will build the foundations for successful careers. Hence, a young person’s first manager is likely to be most influential in shaping their career.

Good Managers do not Give-Up on Subordinates

Good managers can identify subordinates with whom they can work effectively, the people with whom they are compatible and whose body chemistry agrees with their own.

This does not always work well, but they give up on a subordinate more slowly because that means giving up on themselves – on their judgment and ability in selecting, training, and motivating people.

In contrast, less effective managers select subordinates more quickly and give up on them more easily, believing that the inadequacy is that of the subordinate, not of themselves.

Young talent is rarely exposed to good managers

New graduates rarely get to work closely with experienced middle managers or upper-level executives. Normally, they are bossed by first-line managers who tend to be the least experienced and least effective in the organization.

More often than not, first-line managers are either “old pros” who have been judged as

lacking competence for higher levels of responsibility, or they are younger people who are making the transition from “doing” to “managing.

These managers often lack the knowledge and skills required to develop the productive capabilities of their subordinates. Consequently, many college graduates begin their careers in business under the worst possible circumstances.

Since they know their abilities are not being developed or used, they quite naturally soon become negative toward their jobs, employers, and business careers.

Hence, the industry’s greatest is to rectify the underdevelopment, underutilization, and ineffective management and use of its most valuable resource – its young managerial and professional talent.

In organizations, managers wield significant influence in shaping subordinates’ productivity and attitudes. While unskilled managers leave scars on careers, skilled ones – ‘The Pygmalion Managers’ foster growth and confidence.

The Dark Side Of The Pygmalion Effect

The Pygmalion Effect is a double-edged sword. The correlation between reduced expectations and diminished performance is equally significant, exerting detrimental effects on individuals and organizations.

This (known as The Golem effect) can have substantial negative consequences such as:

- Lack of employee self-trust and self-confidence.

- Lack of employee trust in peers and superiors.

- Disregarded ideas.

- Discouraging responsibility.

- Lower productivity.

- Increased chances of employees behaving opportunistically.

- Lack of encouragement in innovative problem solving.

Further, it can even trigger conditions like depression and lack of self-worth which negatively impact personal well-being.

Limitations and Controversies

Many independent studies that tried to reproduce Rosenthal’s classroom experiment failed to establish a correlation. This led many to believe that the Pygmalion effect is not as strong or consistent as it was originally claimed and other factors, such as motivation, feedback, and self-efficacy, may play a more important role in influencing performance.[11],[12]

Most notably, Robert Thorndike[13], an expert in educational and psychological testing and one of several prestigious scholars said, “Pygmalion is so defective technically that one can only regret that it ever got beyond the eyes of the original investigators!”. Thorndike charged Rosenthal with using faulty data from the first IQ test, including impossibly low initial IQ levels, which, he suggested, skewed the later results.

Another study conducted in a retail setting tried to establish a relationship between a supervisor’s expectations of a subordinate. While indicating little evidence of the Pygmalion effect, the results suggested that the effect may have been more operative among men than among women. Whether the Pygmalion effect operates uniformly across genders still remains unresolved.[14]

Furthermore, the Pygmalion effect operates subconsciously and is therefore out of conscious control. The deceptive manipulations that have been used to produce it raise ethical questions when used in organizational settings. Even efforts to train managers explicitly to be Pygmalion have largely failed.[15]

Sources

1. “The Psychological Nursing Interventions Based on Pygmalion Effect Could Alleviate Negative Emotions of Patients with Suspected COVID-19 Patients: a Retrospective Analysis”. National Library of Medicine , https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8764294/. Accessed 11 Aug 2023

2. “Self-Fulfilling Prophecy in Psychology”. Positivepsychology.com, https://positivepsychology.com/self-fulfilling-prophecy/#psychology-self-fulfilling-prophecy. Accessed 10 Aug 2023

3. “Pygmalion in the Gymnasium”. R. Rosenthal, Elisha Y. Babad, https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Pygmalion-in-the-Gymnasium.-Rosenthal-Babad/3f499739ff398507230b45f14e57256fceb6962f. Accessed 11 Aug 2023

4. “Pygmalion Effect”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pygmalion_effect. Accessed 10 Aug 2023

5. “Golem Effect”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golem_effect. Accessed 10 Aug 2023

6. “Pygmalion in the Classroom”. Robert Rosenthal, https://www.amazon.com/Pygmalion-Classroom-Expectation-Intellectual-Development/dp/B01F81LUM2. Accessed 10 Aug 2023

7. “Pygmalion in Management”. Harvard Business Reveiw, https://hbr.org/2003/01/pygmalion-in-management. Accessed 09 Aug 2023

8. “Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior”. J. W. Atkinson, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13505972/. Accessed 10 Aug 2023

9. “Sweeney’s Miracle”. Association for Entrepreneurship, https://afeusa.org/articles/sweeneys-miracle/. Accessed 11 Aug 2023

10. “The Socialization of Managers: Effects of Expectations on Performance”. David E. Berlew and Douglas T. Hall, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2391245. Accessed 11 Aug 2023

11. “Being Honest About the Pygmalion Effect”. Discover Magazine, https://www.discovermagazine.com/mind/being-honest-about-the-pygmalion-effect. Accessed 11 Aug 2023

12. “The Expectations of Pygmalion’s Creators”. Charolette Taylor, https://files.ascd.org/staticfiles/ascd/pdf/journals/ed_lead/el_197011_taylor.pdf. Accessed 11 Aug 2023

13. “Robert L. Thorndike”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_L._Thorndike. Accessed 11 Aug 2023

14. “Pygmalion goes to work: The effects of supervisor expectations in a retail setting.”. Sutton, C. D., & Woodman, R. W., https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0021-9010.74.6.943. Accessed 11 Aug 2023

15. “Problems with the pygmalion effect and some proposed solutions”. Edwin Locke, https://www.academia.edu/34255781/Problems_with_the_pygmalion_effect_and_some_proposed_solutions. Accessed 11 Aug 2023