Businesses operate in a world of hyper-competition where demand is often insufficient to sustain all providers of goods and services. The foundation on which companies traditionally based their dominance no longer holds.

Changes in information technology, financial systems, production techniques, and the rise of companies offering distribution and support systems which previously only the largest companies could afford have removed the advantages of being big.

Today, winning firms are those that successfully master business critical issues, have a holistic understanding of their business environment and use that understanding to take well-timed actions to stay ahead of rivals.

What is Competitive Intelligence (CI)

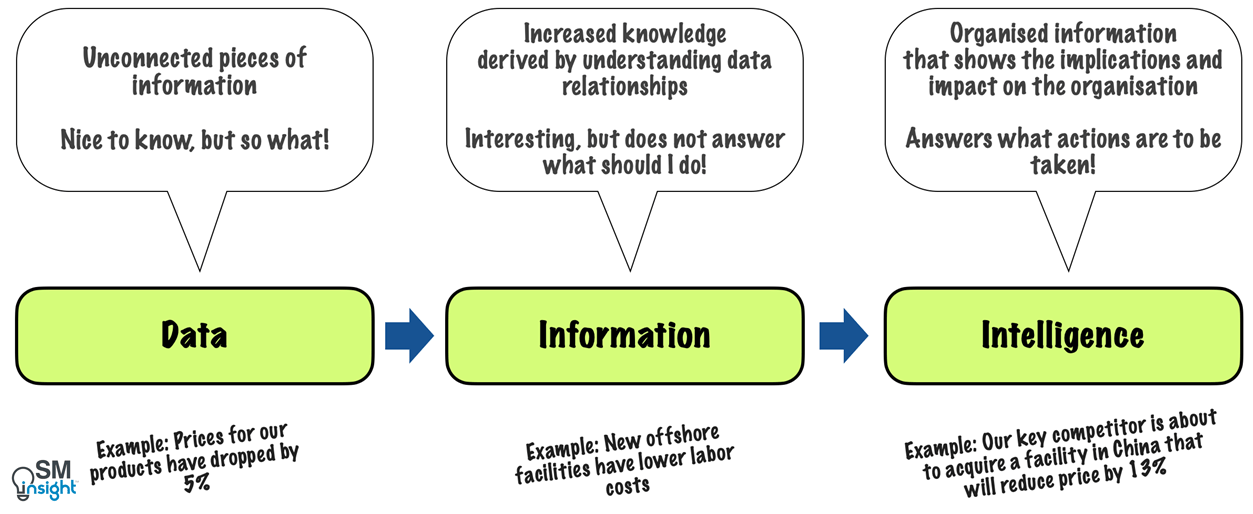

Competitive intelligence (CI) provides a systematic process of information retrieval and analysis in which fragmented (raw) information on competitors, customers, markets, technologies, and macroeconomics are transformed into a vivid understanding of the corporate environment that aids business decision-making.

CI is about leveraging the knowledge assets of the firm, while at the same time determining how competitors are likely to leverage theirs. It is the process of going from data to information to actionable intelligence.

Origin and Evolution of CI

Though elements of organizational intelligence have been a part of business for many years, the history of CI arguably began in the U.S. in the 1970s. In 1980, Michael Porter published the study Competitive-Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors [2] which is widely viewed as the foundation of modern CI.

The discipline has since been extended, most notably by contributions from Craig Fleisher [3] and Babette Bensoussan [4], who through several popular books, added 48 commonly applied analysis techniques to the CI toolkit [5].

In 1988, Dr. Benjamin Gilad paved the way for the CI evolution in US corporations – many of which emulated the basic principles of Gilad’s CI process model [6]. In 1986, the Society of Competitive Intelligence Professionals was founded in the United States and grew to around 6,000 members worldwide by the late 90s [7].

Today, most multinational companies as diverse as Coca-Cola, P&G, Microsoft, GE, AT&T, L’Oréal, Mitsubishi, and Shell – all have a dedicated CI function that is used to aid strategic and operational decision-making.

From ‘competitor’ intelligence to ‘competitive’ intelligence

In its early days, CI was about ‘competitor intelligence’ which involved observing other players in the market, comparing their operations, and predicting their next moves. This approach relied heavily on benchmarking, where comparisons were made between a firm and its rivals.

The result of such an exercise was a report that showed areas of superiority over a firm’s competitors and flagged those in which it lagged. The strategy was then guided by efforts to maintain advantages while closing the gaps in areas where rivals outperformed.

However, this process had several shortcomings and firms soon realised that simple benchmarking was insufficient to maintain lasting advantage.

In 1997, Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne of the Insead Business School studied 30 companies across the world to uncover the factors that lead to high growth. They found that winning firms were those that concerned themselves less with their opponents and their industry’s accepted wisdom. Instead, they concentrated on what the customers wanted and devised innovations that delivered radical improvements in value [8]. There are numerous real-world examples to back these findings.

For example, In the mid-1980s, IBM and Compaq became locked in a struggle to produce

technologically sophisticated, feature-laden desk computers imitating each other’s marginal enhancements. Both failed to recognize that they were offering expensive complexity when customers wanted cheap and easy-to-use machines. By the end of the 1980s, both lost market share to seemingly less well-placed firms that offered low-price, user-friendly PCs.

Firms accustomed to seeing only rivals as a competitive danger fail to detect and respond to aggressive newcomers. Xerox failed to spot Canon’s ability to break into its market because the Japanese company was not perceived as a reprographic equipment manufacturer. US car makers regarded Honda as a motorcycle producer and woke up too late.

Even firms that have attained pole position in terms of product excellence, a coveted goal for many enterprises, are not immune to competitive risks. Encyclopedia Britannica was proud of its ‘best of breed’ encyclopedia and had enjoyed a long period of dominance. But when Microsoft introduced the electronic Encarta encyclopedia, Britannica struggled just to stay in business [9].

Thus, there is enough proof that mere competitor intelligence is insufficient to guard a firm against competitive threats. Firms require a much wider sweep of vision that goes beyond knowing their rival firms and what they are up to.

Competitive intelligence as it stands today

CI today includes all factors that could endanger or enhance a firm’s revenues and profits. It is intertwined with functions such as ‘market research’, ‘business information’ and ‘knowledge management’ all of which feed and support CI. In terms of scope, CI falls between Business Intelligence which looks at holistic (but internal) aspects of business and Competitor Analysis which focuses purely on a firm’s competitors.

The Strategic Consortium of Intelligence Professionals (SCIP) [7] defines CI as “a systematic and ethical programme for gathering, analysing, and managing any combination of data, information, and knowledge concerning the business environment in which a company operates that, when acted upon, will confer a significant competitive advantage or enable sound decisions to be made. Its primary role is strategic early warning.” [7]

CI pulls together data and information from a very large and strategic view, allowing firms to predict or forecast what is going to happen. This in turn allows them to form strategies to remain competitive by improving their decision-making and performance.

The goal of CI is not a competitive war

Much of CI terms are expressed in the vocabulary of warfare using martial examples but in business, killing competitors is not always an optimum strategy. Firms often increase the size of the pie through cooperation, while competition decides the extent of each player’s winnings. Most markets will have a place for more than one winner.

Tobacco companies, for example, resisted curbs on cigarette advertising by arguing that their adverts merely shifted market share from one player to another but did not increase the total demand for tobacco products.

In CI, ‘winning’ is not about beating one’s rivals if this relative superiority does not translate

into higher profits. Instead, it involves seeking a bigger absolute return, even if this means competitors also make more money.

How firms approach CI

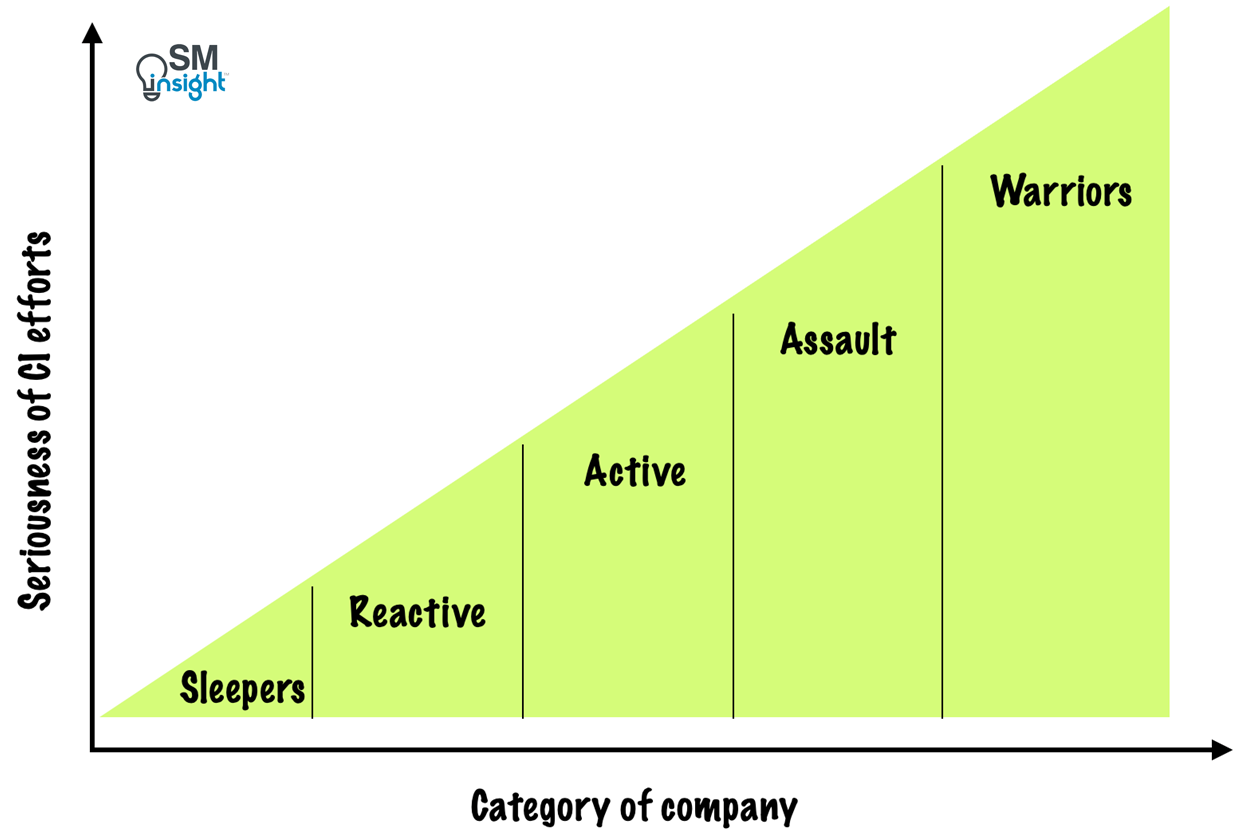

While the benefits of CI are well established, corporate attitudes towards it vary from firm to firm. A study by Rouach and Santi titled “Competitive Intelligence Adds Value” [10] classified firms into five categories based on attitude towards CI and the amount of resource allocated:

These categories are as follows:

- Sleepers: These are firms least interested in CI and have no deliberate CI activity. They are led by a passive management that believes they already know all they need to run the business.

- Reactive: These firms approach CI with a reactive attitude. They have no regular CI operation but will undertake some ad hoc CI exercises when faced with an overt competitive challenge. Most SMEs (small- and medium-sized enterprises) fall under this category.

- Active: These firms approach CI actively and have a permanent CI function. They try to anticipate opportunities and threats rather than respond to them when they become prominent. They dedicate modest resources but lack a formally developed structure to handle CI information.

- Assault and Warriors: These firms take CI very seriously and devote considerable resources to it. Warriors, which are at the top end of the scale, have a provision of a dedicated ‘war room’ for the operations. They conduct extensive patent searches, cast dragnet for counterfeit versions of their products and play war games.

AT&T, Hoffman Laroche, L’Oréal, Mitsubishi and Shell are some of the companies that belong to the warrior segment. [11]

This disparity in the level of CI across companies stems from four reasons:

- First, a lot of firms are either unaware of CI or regard it as not worth pursuing.

- Second, firms undertaking CI do so at a very low level of commitment and intensity. It remains a small-scale, sporadic activity inspired by a desire to match the superior practices of competitors or as a ‘knee-jerk’ reaction to sudden events.

- Third, many firms see CI as the preserve of large, well-resourced businesses.

- Fourth, even when a more developed CI program is in place, it receives meager resources and is understaffed.

Guidelines for Conducting CI

While there is no such thing as an organizational master model for CI, firms can maximize returns from their CI efforts by following the guidelines below:

1. CI should be a part of everyone’s job description

CI is too important to be left to a particular department or a few individuals. Every member of an organization, whatever their role, must remain alert for useful intelligence. But this is easier said than done. Open-ended tasks that are everybody’s responsibility usually end up being no one’s responsibility.

The problem worsens as the size of the organization increases. Individuals in smaller firms have a clear view of strategy and a good understanding of what information can be valuable. Lines of communication are short and new data can be easily exchanged and converted into intelligence. In bigger firms, however, promoting a shared understanding of strategy and goals, together with the exchange of information and its conversion into intelligence, is far more daunting.

Irrespective of their size, firms must overcome two main obstacles to put an effective CI in place:

Promote a culture of knowledge-sharing

Tremendous value is lost if vital information is in the hands of a company employee, but light years away from the decision-maker. Individuals and departments interpret the value of knowledge in terms of their narrow interests.

A culture where sharing knowledge is seen as more personally beneficial than keeping it to oneself can help overcome such gaps. However, leaders must strike a balance between protecting secrecy and sharing knowledge as information can also contain sensitive elements such as client confidentiality, legislative requirements, security measures etc.

While excessive secrecy inhibits group learning which provides such a strong foundation for corporate success, excessive openness can be competitively damaging.

Filtering intelligence from the noise

Filtering commercially significant information from everyday chat and getting that precious intelligence into the hands of the decision-makers is crucial. For example, gossip can be an extremely efficient method for gathering information, but an extremely inefficient way to distribute it.

2. CI is a distinct business function

While CI awareness should be universal, the function itself must be organized as a special responsibility. This includes:

- Making CI one of several duties of an employee(s)

- Making it the sole duty of an employee

- Forming a discreet CI unit

- Involving external consultants – can range from one-off help with a project to continuous monitoring of certain subjects to outsourcing the whole CI function.

- Appointing a board-level director (such as in P&G) who takes charge and reports directly to the CEO. In such organizations, CI is given high priority along with substantial resource support.

Irrespective of the arrangement, a CI analyst must be capable of thinking like a CEO and be privy to the strategic thinking of senior management. An analyst without access to the secrets of the executive suite can bring little intelligence to the table.

3. CI can be both Tactical and Strategic

CI can contribute to both strategic and tactical efforts, but the strategic one is more crucial and must receive priority.

Tactical CI

Tactical CI focuses on short-term factors such as industry-specific buying trends, competitor’s product offerings, pricing, product promotion and geographic reach of products. It requires a constant ‘ear to the ground’ and knowledge of the current landscape.

The goal of tactical CI is to inform the day-to-day operations to capture market share or increase revenue. An airline’s tactical CI, for example, may involve research to inform pricing so that fares are adjusted frequently, even daily, based on competitors’ current tactics.

Strategic CI

Strategic CI focuses on long-term issues, such as key risks and opportunities facing the enterprise. It answers questions such as:

- What do the next five years look like for the firm?

- What competitive changes will affect the organization’s growth plans?

- What events in the market today can change future outcomes?

- What new technologies can pose a threat in the medium to long term?

The prime role of strategic CI is to supply the intelligence needed to craft and sustain a long-term winning strategy.

4. Timing is crucial

Time is the enemy of CI. Knowing something weeks after a firm was supposed to act is of little value. Hence, analysts must address two critical questions:

- Where to get the information, and

- How long will it take.

This requires deliberate and strong CI efforts. Using event-to-knowledge metrics to measure response time is an effective way for firms to keep track of their efforts.

5. CI requires a universal sweep

CI requires a very broad scope that includes competitors as well as factors internal and external to the organization. Focus on the following three areas is crucial:

- Understanding how firms compete.

- Understanding key internal business drivers of a firm.

- Understanding key external business drivers that impact a firm.

Understanding how firms compete

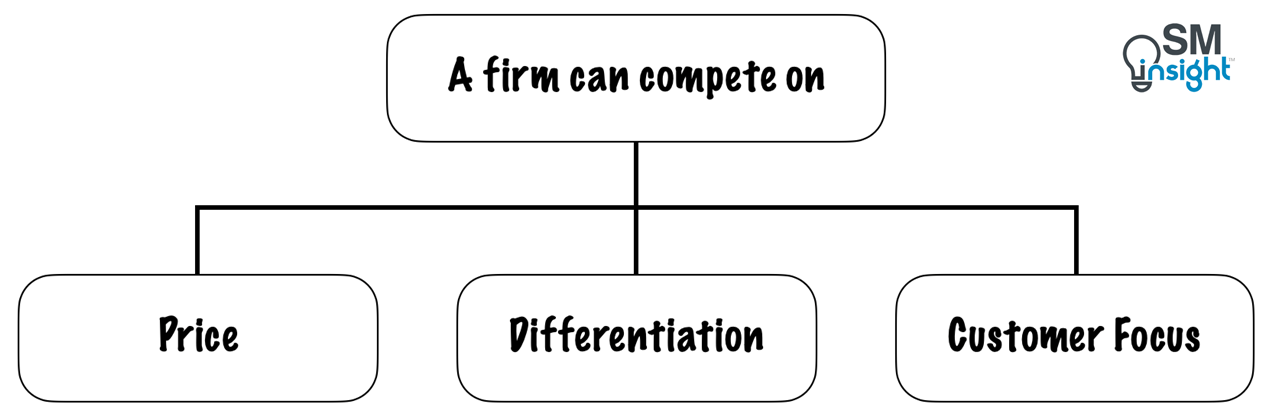

Traditionally, price was the only deciding factor in choosing which supplier to buy from. This is no longer true. In his 1980 book Competitive Strategy [2], Michael Porter showed that there were three dimensions to competition:

Competing firms employ a mix of these dimensions or even all three of them.

Price Strategy also known as cost leadership strategy, is one where a firm sets out to become the low-cost producer in its industry. This may include economies of scale, proprietary technology, preferential access to raw materials and other factors. Walmart, renowned for its operational efficiency and low prices is a classic example.

Differentiation strategy – where a firm creates unique products, services, or brand identities that distinguish it from competitors. By emphasizing factors like design, features, technology, quality, or customer service, the firm offers superior value, commanding premium prices and building customer loyalty. Example: Apple’s focus on innovative design and user experience.

Focus strategy – targeting a specific market segment or niche to tailor products, services, or marketing efforts and meet that segment’s unique needs. Firms in this category serve a narrow customer base more effectively than broader competitors. Examples include Lululemon which focuses on premium athletic apparel and yoga-inspired clothing to cater to fitness enthusiasts and those seeking high-quality activewear.

Understanding key internal business drivers of a firm

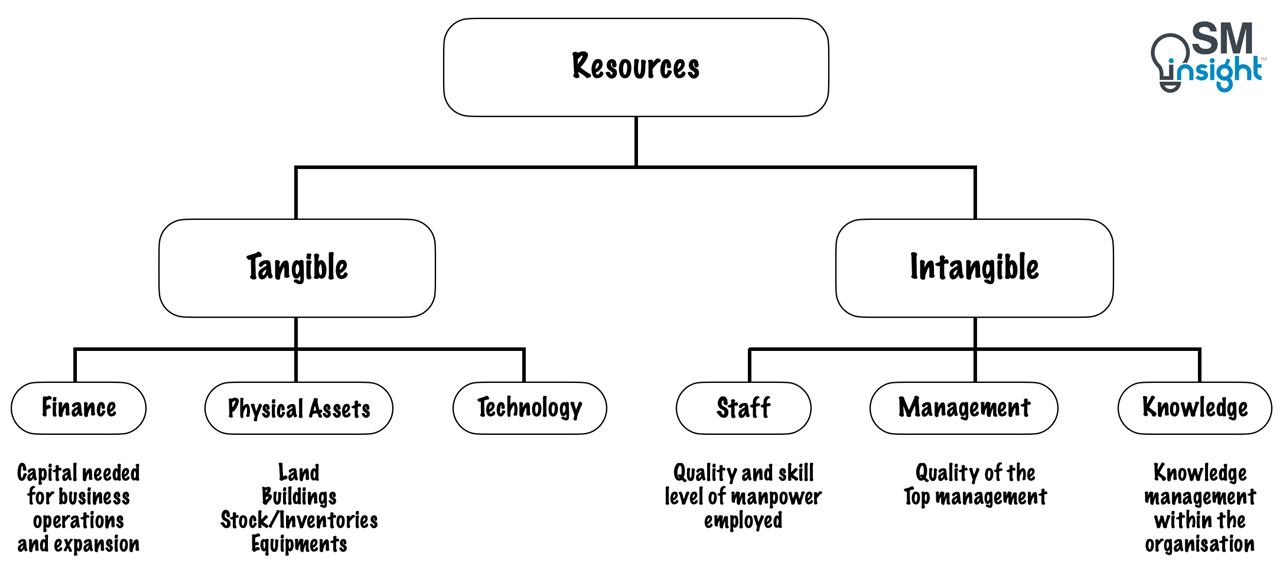

A firm’s competitive capability also depends upon the resources at its disposal and how efficiently they are put to use. Some of the key internal business drivers include:

Resources

Include both tangible and intangible factors that contribute to a firm’s output. Some of the types of resources common to most firms are as shown:

Business processes

These represent the second category of internal drivers and involve activities such as R&D, production, marketing and customer service. Weaknesses in any of the firm’s processes can undermine excellence in others.

A good way to analyze a firm’s processes is Value Chain Analysis [12] which helps understand the complexities and improve them to produce more customer value.

Alliances

A firm’s reach in terms of resources can extend far beyond the assets it owns. Alliances enable enterprises to use resources held by other parties. Cooperation between firms can take many forms that go beyond buyer-supplier relationship and can include:

- Licensing agreements to make or distribute certain products.

- Joint research and development.

- Joint Production.

- Joint ventures or acquiring of minority shareholdings in other companies.

When performing CI, alliances are typically easy to spot but not necessarily as easy to interpret accurately. Most are described in publicly released material issued such as press releases, stock exchange announcements, circulars to shareholders and annual reports.

Understanding key external business drivers that impact a firm

CI analysts need to be aware of a myriad of external factors that may affect a firm externally. A broad scan of the total business environment helps identify potential risks and opportunities. While most external factors are not within a firm’s control, being prepared vastly increases the chances of success.

Several established management frameworks can help firms scan the external environment and detect dangers in advance. Some of them include SWOT analysis [13], Porter’s Five Forces Model [14], Value Net Model [15], Four Corner Analysis [16], Supply Chain Analysis [17], Customer Segmentation Analysis [18], PEST(EL) [19] and STEEP Analysis [20].

Navigating the legal and ethical aspects

CI is not industrial espionage, but by its very nature, it raises serious issues of legality and business ethics. Because the potential rewards for business success are so great, not only in terms of material wealth but also in the prestige and influence arising from it, the incentive to bend or break the rules is extremely powerful.

Back in the 1960s and 70s, CI analysts had a ‘sleazy’ reputation and were branded as corporate spies. Companies used Illicit means to gather intelligence including breaking into the offices of rivals, tapping phones, intercepting communication, planting moles, or even placing rogue executives as members of the rival’s management team.

According to data shared by the FBI in 1996, companies had reported over $1.5 billion in losses because of industrial espionage [21]. This triggered the Industrial Espionage Act in the U.S. that made the theft of trade secrets a federal offense and laid down stiff penalties with fines as high as $10 million and prison sentences of up to 15 years [22].

To work within the confines of the law, CI analysts must have a clear understanding of what constitutes lawful and ethical CI. The SCIP has developed guidelines for ethical behavior for competitive and market intelligence activities. Firms and practitioners can develop their own standards along the below seven-point spectrum [23]:

- Elevate the Profession – To continually strive to increase the recognition and respect of the profession.

- Always in Compliance – To comply with all applicable laws, domestic and international.

- Transparent – To accurately disclose all relevant information, including one’s identity and organization, prior to all interviews.

- Conflict-Free – To avoid conflicts of interest in fulfilling one’s duties.

- Honest – To provide honest and realistic recommendations and conclusions in the execution of one’s duties.

- Act as an Ambassador – To promote the SCIP Code of Ethics within one’s company, with third-party contractors and within the entire profession.

- Strategically Aligned – To faithfully adhere to and abide by one’s company policies, objectives and guidelines.

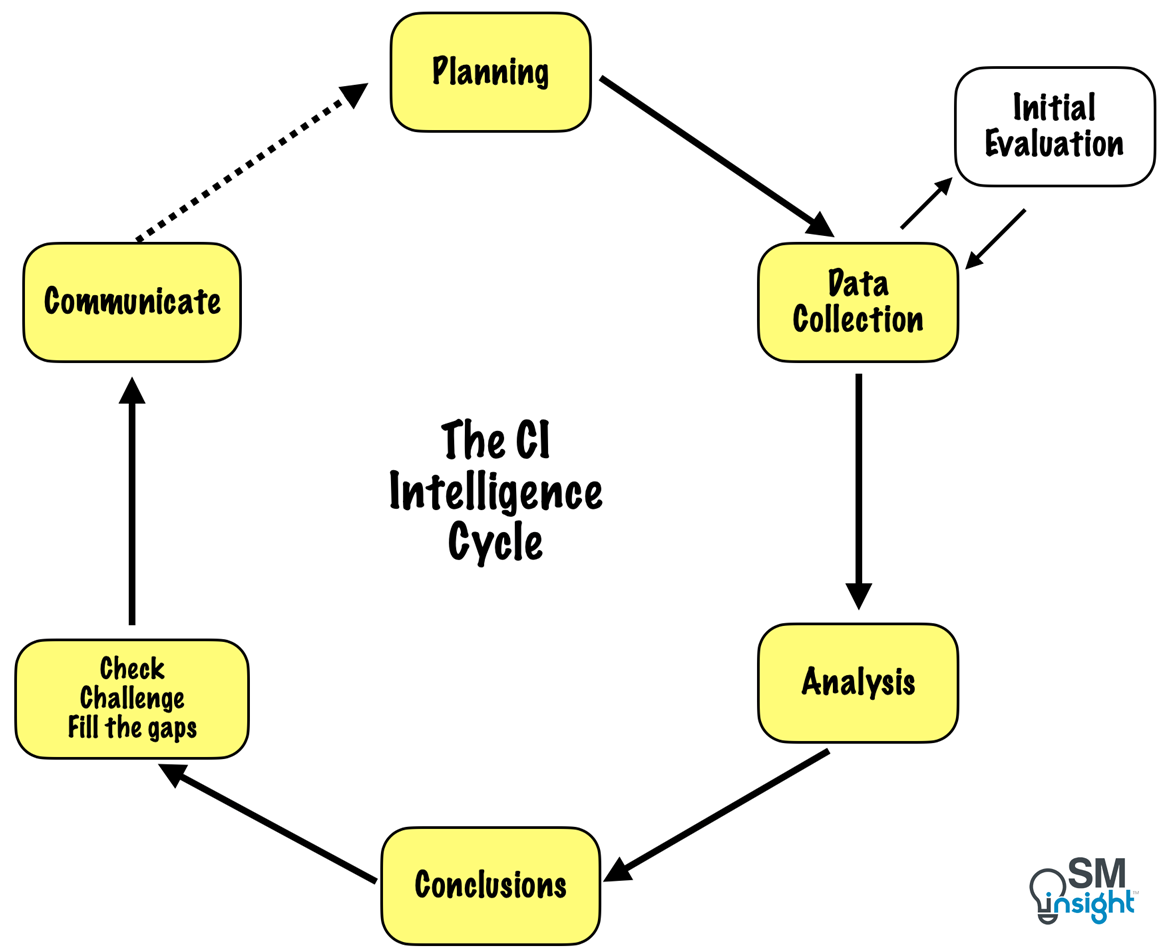

The CI Intelligence cycle

The process of creating actionable intelligence in CI follows several steps and is largely influenced by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) [24] model.

It consists of the following steps:

The process is cyclical because new intelligence often generates further demands from its recipients. Each of the steps is explained in more detail:

1. Planning

Planning consists of two stages – functional and project-level planning.

Functional planning

Functional planning concerns with the question of ‘where to begin?’. Often, this can be one of the most difficult challenges as there can be many potential areas of interest. One helpful method to organize and prioritize CI needs is to focus on Key Intelligence Topics (KITS).

KITs can include:

- Strategic decisions and actions – moves that have a significant impact on the performance and value of the business.

- Early warning topics – issues that are not presently included in management’s assessment of the competitive situation but which could be of future significance.

- Description of key players in the market – the traditional role of the more limited ‘competitor- intelligence’.

- Counterintelligence –identification and neutralization of numerous threats posed by rivals’ intelligence services and the manipulation of those services.

Project level planning

Project-level planning establishes the purpose and potential usefulness of CI by answering elementary questions such as:

- What is the problem that finding a particular piece of intelligence would help solve?

- To what extent will a firm lose by not obtaining that information?

- How will a firm’s action be affected by obtaining the information?

Once the objectives of the project are clearly understood and its prospective value justified, the analyst can move to the second stage in the intelligence cycle which is to gather data.

2. Data Collection

Performing CI requires a deep understanding and a solid grasp of research techniques. Gathering information involves devoting the time, trouble and expense required for collection, collation, and distribution. Asking the question – ‘What would motivate someone to assemble information on this topic?’ can often point to the right sources.

The process of research broadly follows the following steps:

Defining a research framework

Crafting a research framework helps assign proper weightage to different sources and reduces the likelihood of overlooking areas that may later prove to be important. It is about identifying which sources to approach and in what priority.

For example, there may be only one opportunity to interview a key resource or visit a company’s office. Hence, it is important to harvest information from more accessible sources before approaching the valuable ones.

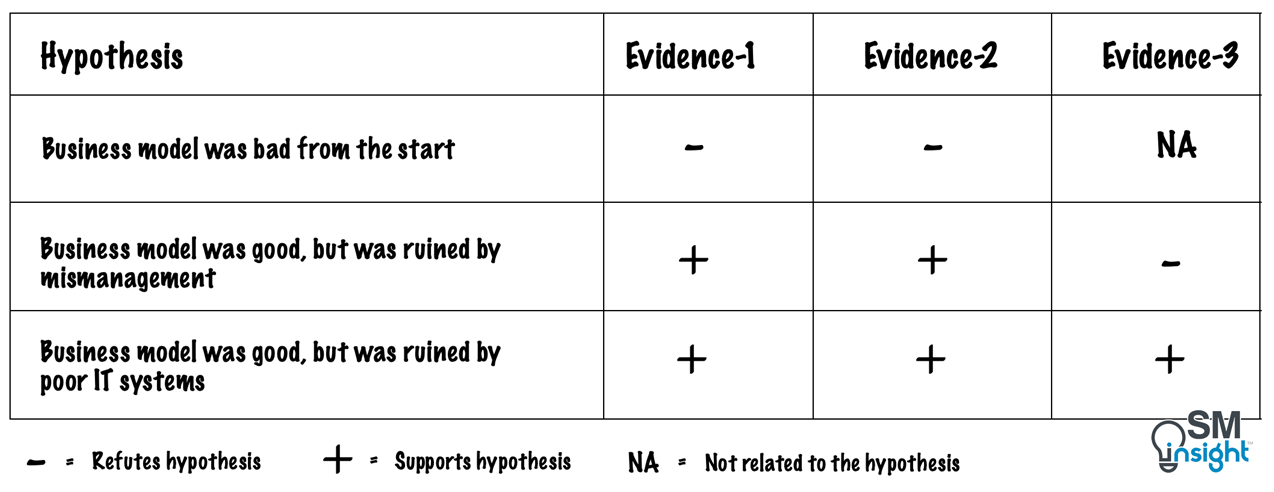

Research must begin with a hypothesis

CI research revolves around formulating and proving a hypothesis. Establishing an initial hypothesis is essential to serve as an analytical pivot. Relying solely on collecting data with the hope that a pattern will emerge can prove inefficient.

This initial hypothesis need not be correct. Its purpose is to serve as the engine for generating truth. It can either be confirmed or refuted as the research progresses – even an erroneous idea can be a launch pad for the project and provide the initial direction. Some CI analysts also table several competing hypotheses to aid their research.

Leverage Internal sources of information

Researchers often neglect the importance of in-house sources while focusing on external ones. It is estimated that 70% to 80% of intelligence resides within organizations’ employees or, internal marketing networks, as they are the team that gains information when interacting with suppliers, customers and other industry contacts [25].

While obtaining data from in-house sources is naturally easier, they must be validated using external sources as they can sometimes be incorrect or misleading.

Management support is important

Research staff members must be given adequate resources if satisfactory results are to be achieved. Seeking data costs money and the organization must be prepared to pay for it. To develop a robust CI process, management must also encourage and support the professional development of its researchers and CI practitioners.

Data collection should begin with the sector

Competing firms always operate within the environment of their industry (or sector) and not in isolation. Activities of rival firms are conditioned by and take place within these sectoral contexts. Certain descriptive characteristics apply to all sectors, some of which are:

- Market Size: usually expressed in value or volume terms, they indicate the size of the addressable market. Historic and prospective growth rates are also of vital importance to predict the direction of growth.

- Time-dependent patterns in demand: some sectors (e.g.: utilities or supermarkets) are immune to fluctuations while in others, demand can vary dependent upon the general state of the economy. It is important to identify such patterns specific to the sector in which a firm belongs.

- Market segment: describes the nature of the market being addressed and can vary from a highly localized marketplace to one extending over the whole country or to a worldwide audience. The complexity of market segmentation requires a careful study as firms in the ‘same industry’ may be offering very different goods and services or addressing completely dissimilar sets of customers.

- Supply structure: describes the supply characteristics of a sector and can range from a highly concentrated one where a few players dominate the market, to a highly fragmented one where numerous competitors hold small individual shares.

The concentration ratio serves as an indicator of competition levels, with a high ratio suggesting intense competition in contrast to the subdued competitive environment of a fragmented market. The ease with which new competitors can enter a market is an imperative consideration as barriers to entry offer protection to existing players.

Sources of information to analyze sectors

To gain the sectorial understanding discussed previously, CI analysts can muster a wide variety of sources. Some of the good ones include:

- Trade Associations – provide information such as the number of firms in a line of business, size of a sector, rate of growth and major issues concerning it. Often such information is available free of charge or is modestly priced.

- Official Statistics – provide both macroeconomic indicators and information relating to individual sectors and market segments. Nearly every country has a central public sector unit entirely devoted to the production, harmonization and dissemination of official statistics that is needed to run, monitor and evaluate the operations and policies [26].

- Individual Companies –firms operating within a sector can be a powerful source of information. Annual reports of public companies refer to general market conditions and key industry issues that affect their business or have a future impact.

BP, the British multinational oil and gas company, for example, has been publishing a report on the world energy scenario titled “Statistical Review of World Energy” since 1951 [27]. A large number of technology firms also issue White Papers that are an excellent source of enlightenment on major topics within an industry. Another valuable source is reports issued by the leading consultancies firms, some of which are freely available (e.g.: McKinsey Insights [28]). - Market Research – they are an excellent source of obtaining industry overviews along with information such as size, structure, trends, and other key aspects. They often identify the main players and profile them. Market research also includes forecasts of future industry growth and key market statistics, that are usually not found in trade association data.

- Brokers’ Research – valuable sources of information especially when they are studies of sectors rather than individual companies. While they contain useful facts and analyses, they must be adjusted for optimistic bias.

- Monographs – are ‘grey literature’ – the sort of material not disseminated through conventional publishing channels. They include unpublished academic theses, scholarly papers, business school case studies etc. These works are usually available at a reasonable price but date quickly.

- Journals –are a crucial source of current (and retrospective) industry understanding. For example, the Financial Times sectoral surveys provide an excellent overview of different lines of business, outline the most pressing current issues affecting them and profile some individual players. Several trade journals offer annual surveys of major events and trends in their line of business.

- Regulatory Authorities – When a sector is subject to public regulation, a great deal of high-quality information may be available at a modest cost. Public watchdogs overseeing specific sectors are also excellent targets for research.

By drawing upon each of the above types of sources, researchers can leverage their individual good points and offset their deficiencies to gain a well-rounded and up-to-date picture of a sector.

Initial Evaluation

Research is not only an iterative process but also an interactive one. It is important to gain insights and guidance from colleagues/users which may necessitate a change in direction.

Also, proving or disproving a hypothesis is often a lengthy process of gathering and examining evidence. Information obtained in the first phase of research may support a theory, but still not conclusively prove it.

Bias can also arise when hypotheses are considered in sequence. Simultaneous (rather than sequential) evaluation of the hypothesis can avoid being over-committed to the ‘correct’ hypothesis and ignoring other possibilities.

Constructing a matrix setting out the various hypotheses to see which pieces of evidence support or refute them provides a quick visual check on the degree of support each theory receives from the data:

Errors can also creep into the analysis when conclusions reached by analysts rest upon prevalent and long-held beliefs that escape scrutiny and remain unchallenged. One way to tackle this is through Linchpin Analysis [5].

Developed by the CIA in the 1990s, the Linchpin technique helps avoid what is known as “intelligence myopia”. It consists of five steps:

- List all the underlying assumptions that were accumulated about a competitor or competitive situation.

- Develop judgments and hypotheses about a recent competitor decision or their marketplace action against those assumptions.

- Take one key assumption (that is, a linchpin) and, for the sake of argument, either eliminate it or reverse it.

- Re-evaluate the evidence in light of this changed or deleted assumption and generate a new set of hypotheses and judgments.

- Re-insert the assumption that was eliminated or reversed and determine whether the new judgments still hold accurate.

When properly used, linchpin analysis can provide a beneficial contrast to an out-of-date view and provide an objective reality check to competitive analysis.

Researching individual firms

Equipped with the requisite industry knowledge, an analyst can begin to research individual firms. Some of the common sources from which information include:

Periodic filings

Financial results – balance sheets, profit and loss statements, cash flow statements and accounting notes. Also include business outlook, director’s reports, chairman’s statements, and other accompanying reports that companies release with the periodic filing.

Corporate external communications

A vast majority of companies must impress potential customers and maintain the loyalty of existing ones through publicity via their website, advertising, and similar promotional avenues. These can be valuable sources of information.

For example, analyzing a firm’s advertising can provide clues as to the market segments it is concentrating on, its strongest selling points, the mode of competition (price, differentiation, or market segmentation) and the public persona it wishes to project.

Similarly, public companies communicate with the investment community through presentations and investor calls that provide excellent insights into their business plans. Promotional emails are also a good way of keeping tabs on a firm’s marketing campaigns.

Trade shows

Trade shows and exhibitions are events where firms tell the world about what they are doing. They can be excellent sources for information such as:

- Product range and lead products.

- New or recent products and services.

- Upcoming offerings and their likely availability.

- Information on elements in the firm’s portfolio that receive the most attention.

- The technological level attained by a company as reflected in its offerings.

- The segments or types of customers a rival firm is targeting.

- Reactions of attendees – potential customers, industry rivals, consultants etc.

Circulars

Listed firms send circulars to their shareholders under certain circumstances. This includes ‘material’ acquisitions or disposals of other companies, businesses or assets which could be pointers for major events.

Patents

Searching through patents as a means of obtaining competitive advantage has a long history. Bayer started analyzing competitors’ patents in 1886. Patent analysis can provide descriptive clues regarding a company’s technological trajectory and the markets it is concentrating on. It can also identify commercial opportunities presented by the expiration of rival’s patents or those involving a potential to manufacture under license with other firms.

Asset ownership

Changes in asset ownership by companies can indicate a shift in strategy or business direction.

Company visits

Visits to a firm’s premises can reveal valuable insights such as the nature and productive capacity of a plant, the number of employees at a particular site, a rough estimate of property values and costs etc. CI analysts should seek information from colleagues, particularly the sales force, who undertake company visits in the normal course of business.

Leveraging human intelligence sources

Published data alone is insufficient to feed the information required for CI. A vast reservoir of intelligence resides in people’s minds. To tap this, analysts must make direct contact with them. An effective way to access this valuable information is by conducting interviews which involves the following steps:

- Planning: involves gathering background information on the individual to be interviewed, their company, salient features and major industry issues.

- Identifying subjects to approach –determining the appropriate person to approach for the task. Search engines, databases, or directories can be used for potential contacts. Sometimes primary contacts can be elusive. In such cases, a firm’s PR department, personnel section, or assistant can be reached for assistance.

- Approaching by email – emailing before a phone call increases the likelihood of securing an interview. It also serves as a tangible link and enhances authenticity when compared to a phone call. However, emails are easier to ignore, hence must be specific and include a call to action.

- Persuading people to be interviewed – when approaching potential interviewees, researchers must truthfully disclose their identity, the name of the organization they represent and the purpose of the interview in line with the SCIP code of ethics.

- Coping with refusals – while it can be disappointing for a prospective interviewee to turn one down, there is no point in being too pushy in trying to make them change their minds. The best approach is to accept their refusal graciously. It might be worth asking them to nominate an alternative person to interview, either a colleague or someone in another organization.

- Deciding the length and timing of interviews – The interviewer must have a reasonably good idea of how long an interview will last. They must be prepared to negotiate the length of time and table more important questions while skipping the lower-priority ones if necessary.

- Conducting the interview – CI interviews tend to be open-ended, allowing the respondent to qualify, elaborate or explain an answer. Hence, the questioner must also be on alert for potentially valuable information that may not be a part of the brief.

Conducting an interview involves the tricky task of guiding the course of the interview without appearing bossy, impatient, bored, or mechanical. Respondents straying too far from the issue must be tactfully nudged on or led back to the point. - Generating a record of the interview – while some interviewers prefer audio or video recordings for records, this can make interviewees more reserved. Operating equipment can be distracting and can hinder personal interaction. Note-taking is a good alternative, provided it is done carefully (and not excessively) without disturbing the interview process.

- Sustaining a longer-term relationship with the interviewee – expressing gratitude to the interviewee for their time and contribution helps in building a positive rapport. CI analysts must create a mutually beneficial relationship through periodic contact, and sharing of relevant information, such as journal articles or industry statistics.

3. Analysis

The process of analysis in CI combines both scientific and artistic elements. Out of the complexity, confusion, and uncertainty of the business environment, the CI analyst must bring meaning and offer a credible guide to decision-making.

The process of analysis involves the following steps:

Understanding the customers of the analysis

An analyst’s customers or clients are those individuals in the enterprise who need advice and guidance in decision-making. Often, these individuals may well be one or more steps removed from the analyst’s immediate customer.

To be effective, analysts must understand how their outputs will eventually be used by the decision-makers. Knowing end customers helps define a clear starting point and also an endpoint when a satisfactory product is delivered.

Analysts must communicate with their customers throughout the analysis process and engage in many iterations to improve the final product. An open-minded attitude to the task is essential.

Defining the analysis problem

Customer needs must be interpreted before they can be acted upon. The KITs identified in the functional planning stage of the intelligence cycle must be revisited at this point. It also helps to understand the following before beginning the analysis:

- Why is this project being proposed?

- Has anyone attempted it before?

- Are there some of the barriers to be aware of?

- What data or information has already been gathered on the topic?

- What analysis process will be needed?

- Who has a stake in the outcome?

- What decisions will be made based on my work?

- How quickly is an answer needed or wanted?

- What are the customer’s expectations of the analysis?

- What does the customer want or not want to hear?

- What resources are available to support?

- Is the potential decision worth more than the effort needed?

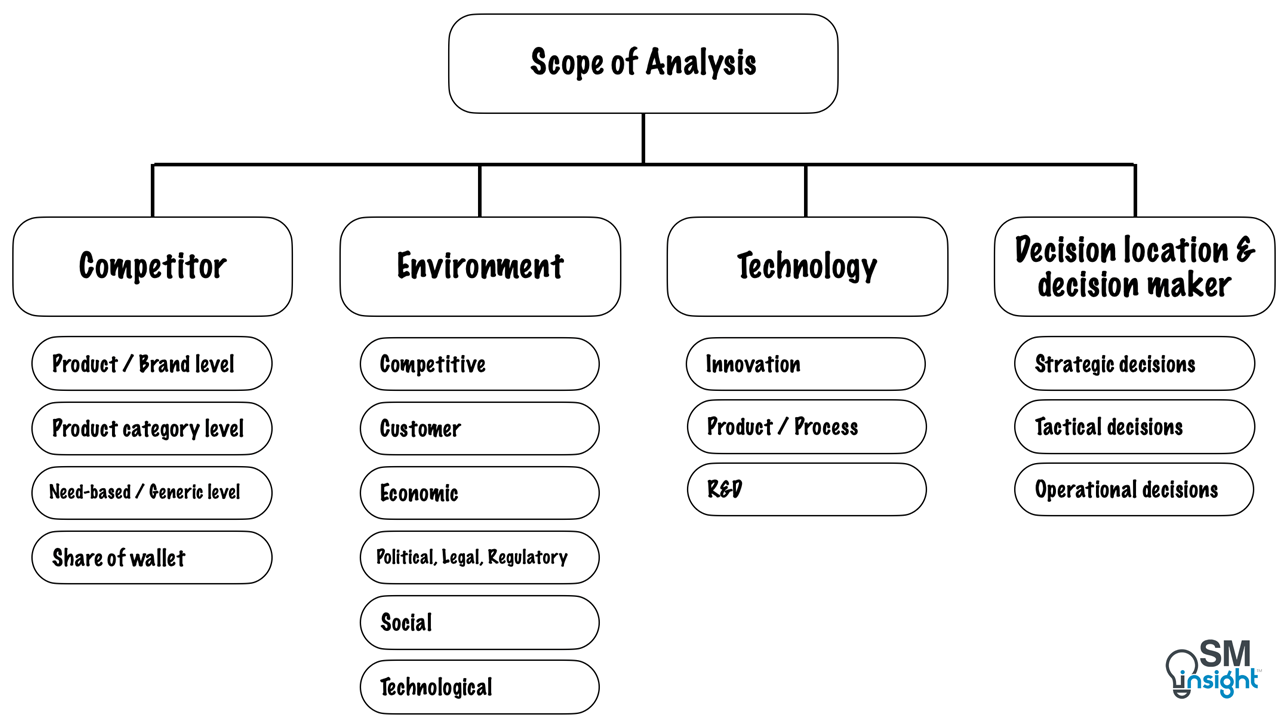

Identifying the scope of the analysis

The scope of the analysis can be better understood by looking through the lens of the following four main categories:

Competitor

This is about predicting either competitor behaviour or competitive environment behaviour and can range from product/brand level (the narrowest perspective an analyst can take) to the share of wallet level which is the broadest category of competition that considers any other product that a customer might choose to buy instead of the firm’s offerings.

Environment

Environment emphasizes the following:

- Competitive – both current and prospective competitors and how they compete.

- Customer – a firm’s current and potential customers and competitor’s customers.

- Economic – issues such as inflation, financial markets, interest rates, price regulations, raw material sourcing, monetary policy, exchange rate volatility etc.

- Political, legal, and regulatory – institutions, governments, pressure groups, and stakeholders that influence the “rules of the game.”

- Social – demographics, wealth distribution, attitudes, and social and cultural characteristics that determine the firm’s purchasers.

Technology

Principally concerned with the technological base of new or emerging capacity. Much of technological analysis focuses on the evolution of science and scientific activity and involves three aspects:

- Innovation – identifying disruptive innovation that might necessitate new or different technologies to compete in the short to medium term.

- Product/process – understand the nature and potential results of process improvements. For companies with technology-intensive products and processes, technology can be an important differentiating factor (e.g.: chip manufacturing).

- R&D – many industries have a large proportion of companies with high R&D activity. These companies are often the most active in developing innovation, as well as product and process improvements.

The intelligence needs of decision-makers in technology environments will vary by industry and position. A flexible approach is needed to respond to unique customer needs.

Decision Location and Decision Maker

Management decisions can differ depending on the level of responsibility and who makes them. Whether they are senior executives at the business unit or corporate level, middle managers from functional areas, or front-line personnel, each have different needs for the outputs an analyst provides.

The issue of geographic complexities can also be added here. Firms increasingly compete in environments that require the analyst to consider all forms of geographical levels of competition, including national, multi-national, and global formats.

Evaluating the inputs to the analysis

Analysts must credibly evaluate input data and consider the following parameters when analyzing information:

- Reliability – Can the source of the information be trusted to deliver reliable information to the analyst? It helps to classify information on a reliability scale:

| Grade | Reliability |

|---|---|

| A | Completely reliable |

| B | Usually reliable |

| C | Fairly reliable |

| D | Not usually reliable |

| E | Unreliable |

| F | Reliability unknown |

- Accuracy – Answers the following questions on collected information:

| Are the data inputs captured “firsthand,” or have they been filtered? |

| Is there any reason to think that there might be any deception involved? |

| Is the source able to communicate the data precisely? |

| Is the source truly competent and knowledgeable about the information they provide? |

| Are the data sources/providers known to have vested interests, hidden agendas, or other biases that might impact the information’s accuracy? |

| Can the source’s data be verified by other sources or otherwise triangulated? |

- Availability – It is important to have substitute sources that can be accessed quickly. Analysts must avoid relying entirely on a single source.

- Ease of access— time and cost to access the source must be weighed against its benefits to make the best use of limited resources. If equivalent data can be gained with less effort, they must be given priority.

Making sense of the analysis

Analysts ultimately respond to decision-makers needs for knowledge. This knowledge can be broken down into five interrelated elements:

Facts

These are verified information, something known to exist or to have occurred. They are unambiguously true statements and are known to be so. Fact-checking and verification is a crucial step for strategic decision-making as many of the facts about competitors and competition are time-sensitive and become dangerously incorrect over time.

Perceptions

These are impressions or opinions that fall short of being facts but are supported to some extent by underlying data or logic. These are often expressed as thoughts or opinions in language such as: “I think that . . .” or “My view is . . .”

An analyst can either test and convert them into facts or use them as is provided everybody knows they are perceptions. Errors can creep in when perceptions are mistakenly regarded as facts.

Beliefs

These are a mix of facts and perceptions and commonly describe cause-effect relationships. They can be both explicit or implicit and must be subjected to verification and justification. Beliefs often influence how individuals understand their world and how they think about the future.

Assumptions

This information is taken for granted. They can be both explicit and implicit. The former type is consciously adopted, well understood, and shared while the latter may escape scrutiny as users may not be aware of them. Assumptions must be consistently and constantly challenged to reflect changing situations and shifting competitive landscape.

Projections

These are composed of a mixture of facts, perceptions, beliefs, and assumptions. An analyst must be able to powerfully defend or justify projections if used as they become a critical part of the knowledge base upon which decisions are made.

Infrastructure to support the analysis process

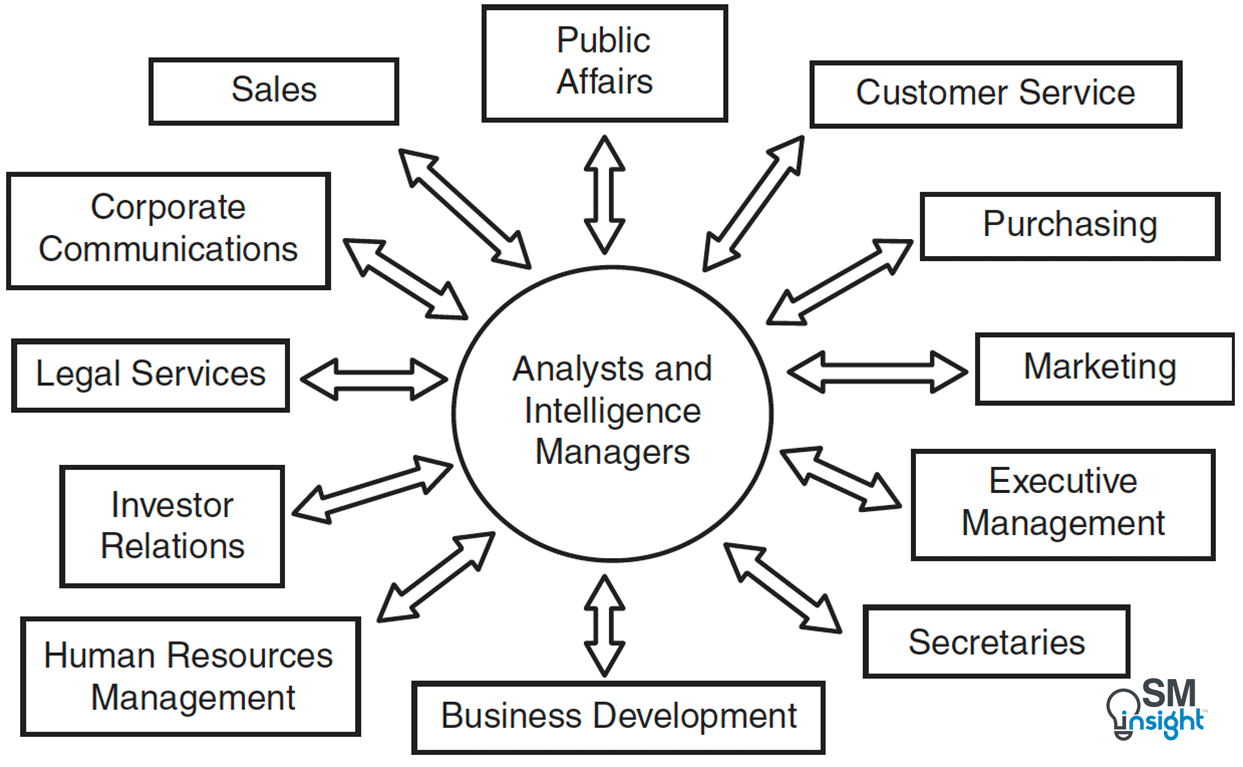

Managing the Internal network

Analysts must be part of established networks aimed at facilitating intelligence sharing throughout the organization. This allows access to individuals who can provide bits of data or information that can often be the “missing piece” in the analytic puzzles.

Even if individuals in the internal network do not have the critical information, they can often point out those individuals who may have it. Key participants of the internal network include:

Managing the external network

External networks are also a key part of the analyst’s contact universe. They include industry experts, industry associations, industry commentators, stock analysts, government experts, government departments, civil servants, respected journalists, subject specialists, and broadcasters to obtain needed data or access to other important stakeholders.

4. Drawing conclusions

CI conclusions must be both accurate and accepted by the consumer of intelligence. The following are important considerations when sharing conclusions with decision-makers:

Avoid contradictions

Regardless of the excellence of work that has gone into preparing the report, it counts for nothing if the analyst lacks credibility owing to self-contradiction. For example, a statement that ‘strengths include rigorous financial discipline’ cannot be reconciled with the later observation that ‘weaknesses include poor cost control’.

Avoid fact-fitting

In a world where data can be untidy, confusing, and baffling, a CI report is expected to be logical, coherent, and persuasive. This can give rise to a temptation to twist, ignore or even invent information to support conclusions.

Analysts need hypotheses to drive forward their enquiries. The danger lies in them becoming so committed to their theories that they deny incompatible evidence or allow such information to fall by the wayside when the final report is written. Acts of fact-fitting are seen as deliberate acts of deception and can seriously damage an analyst’s reputation.

Avoid an excessive desire for certainty

The other side of the coin is a fervent search for accuracy and completeness which can lead to wasteful use of time, energy, and other limited resources. This can lead to a failure in delivering CI on time for it to be acted upon. Balancing accuracy against time is key to enabling good management decisions through CI.

5. Checking, Filling gaps and challenging

The most rigorous way of testing CI conclusions is to have a “B” team of analysts, not involved in the project, examine the data and its interpretation to detect weaknesses. But this is impractical in most cases.

The next best alternative is to try and get a colleague from another functional area to review evidence and findings. Irrespective of who is probing the individual components, the following general tests can be applied:

Organizational impediments

- Have the ideological leanings of the organization been allowed to override the personal judgment of the analyst?

- Did the process of gaining approval from a department head discourage the analyst from straying too far from the ‘safe middle’?

- Have resource limitations impacted the quality of the analysis?

Systemic weaknesses of the analyst

- Is the analyst too knowledgeable about a topic? – being closely connected with a topic can bring complacency or ignorance towards factors outside its traditional frame of reference.

- Is the analysis a superficial assessment because of a lack of knowledge?

- Does the analyst prefer certain types of data (financial statements for example) that may have received greater attention than others?

Flaws in a specific piece of analysis

- Are assumptions being treated as facts?

- Have initial expectations strongly influenced the outcome?

- Was recently collected data given excessive weightage over one obtained earlier?

- Have small, successive changes in the data over time gone unnoticed?

- Are there significant gaps in the coverage?

- Is the chain of logic supporting the findings intact?

- How well do the conclusions stand up to Linchpin’s analysis?

CI analysts are expected to do their job in a dispassionate, objective way. They must constantly battle against their own preconceptions, unchallenged assumptions, prejudices, wishful thinking and pet theories. A good CI analyst must have the emotional humility and intellectual flexibility to change their mind in light of the evidence.

6. Communicating

Conveying results of CI analysis in a timely and effective manner poses a significant challenge and is aggravated by the fact that decision-makers cannot always wait for the analyst to complete their work.

Often, the output of CI is only useful for a short period before it becomes out-of-date. Analysts must hence place considerable attention on delivering findings and gaining the attention, understanding, confidence, and ultimately trust, of their decision makers.

Irrespective of how intelligence is delivered, analysts must emphasize the following:

- Differentiate between strategic and tactical information.

- Highlight decision-oriented information.

- Include only relevant supporting data.

- Distribute reports in a timely, need-to-know basis.

- Share multiple reports versus one large report when possible.

Listed below are some of the common means of delivering intelligence:

Face-to-face briefings

This is one of the most effective two-way models of communication. It not only encourages discussion and exchange of understanding in real-time but also minimizes second-hand distortion or the effects that a time lag can have on the acquired understanding.

Written reports and briefings

Printed outputs are a cost-effective way of distributing results. They are also preferred by some executives. However, more pages are printed than are ever read and much of that information is not fully understood. They also carry the risk of reaching unintended audiences which can create vulnerabilities.

Presentations in Meetings, Seminars, and Workshops

These are an effective way to deliver results to a group of decision-makers and a good way of gaining a group’s attention. They also provide opportunities to discuss findings in real-time, not only with those who may have initiated the task in the first place but also with those individuals to whom it was designed to inform.

One drawback of the method, however, is the effort required to prepare slide decks whereby the aesthetics, fanciness of presentations, or the structure of slides can overpower the important content or message.

E-Mail/Instant Messaging

These are among the most commonly used forms of communication and attract immediate attention and quick replies from decision-makers. They are also a good way to disseminate “alerts,” and other forms of analytical results that need to be acted upon quickly.

Intelligence systems

These are specialized CI systems tailored for analytical use within a firm’s larger corporate communication system. These allow analysts’ clients to see their findings in refined and finished formats, which can include digital links to other materials, including input such as documents, interview notes, articles, and so forth.

Such systems nearly always allow for selective access and viewing by clients on a need-to-know basis and can be designed to send out various forms of information in the form of e-mails or instant messages to a selected number of recipients. However, these systems can be cumbersome, costly, and complex and do not always allow for two-way communication.

News Bulletins and Newsletters

These are targeted towards field sales personnel, marketing, managers, sales managers, or

other decision-makers and focus on current or immediate past events. Newsletters are rarely oriented toward the future and, hence are of lower strategic value. When done well, newsletters and news bulletins can be catalysts for not only conversations and discussions but also encourage new questions to be asked of the analyst group.

Assessments

These are brief and regularly generated products that look at business decisions. They provide an assessment of the current situation facing the decision maker while identifying critical success factors and suggesting probabilities of likely outcomes. Their content can range from a general overview of broad issues to detailed answers to specific questions.

Competitor Profiles

These are produced as needed but are constantly updated and contain information about competitors. They are valuable for functional decision makers (sales, marketing) who not only benefit from their existence but contribute to their augmentation and evolution.

Seldom actionable in their own right, they are of lower strategic importance but can be combined with other types of outputs to provide high decision-making value.

CI tools and the FAROUT model

The CI toolkit consists of hundreds of analytical tools and techniques. Choosing between them can be one of the most difficult tasks facing an analyst. One of the best sources to understand these tools is the book – Strategic and Competitive Analysis by Dr. Fuller and Bensoussan [29] which discusses numerous analytical models and their applications.

The authors have also developed a system referred to as the FAROUT (Forward Oriented, Accurate, Resource Efficient, Objective, Useful, and Timely) for determining the overall effectiveness of an analytical model. FAROUT utilizes a five-point rating scale to assess each analytical technique on a five-point scale ranging from low (1) to high (5) against the six FAROUT elements.

FAROUT scores of a few of the CI tools are shown below for illustration:

| Analytical Method | Future Orientation | Accuracy | Resource Efficiency | Objectivity | Usefulness | Timeliness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry Analysis (Nine Forces) | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Benchmarking | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Critical success factor analysis | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 |

| Linchpin Analysis | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 |

Data source: Strategic and Competitive Analysis [29]

Each CI tool has unique its unique strengths and limitations which multiply in specific organizational contexts. The FAROUT system helps an analyst choose appropriate tools to maximize the insights generated.

Sources

1. “Course 12: Competitive Intelligence”. Excellence in Financial Management (Matt H. Evans), http://www.exinfm.com/training/pdfiles/course12-1.pdf. Accessed 11 May 2024.

2. “Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors”. Michael E. Porter, https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=195. Accessed 13 May 2024.

3. “Dr. Craig S. Fleisher”. Council of Competitive Intelligence Fellows, https://cifellows.com/about-us/cifellows/dr-craig-s-fleisher/. Accessed 13 May 2024.

4. “Babette Bensoussan”. Council of Competitive Intelligence Fellows, https://cifellows.com/about-us/cifellows/babette-bensoussan/. Accessed 13 May 2024.

5. “Business and Competitive Analysis: Effective Application of New and Classic Methods”. Craig Fleisher and Babette Bensoussan, https://www.amazon.com/Business-Competitive-Analysis-Effective-Application/dp/0132161583. Accessed 17 May 2024.

6. “The Academy of Competitive Intelligence (ACI)”. DR. BENJAMIN GILAD, https://academyci.com/about-aci/. Accessed 13 May 2024.

7. “Strategic Consortium of Intelligence Professionals (SCIP)”. Strategic Consortium of Intelligence Professionals (SCIP), https://www.scip.org/. Accessed 11 May 2024.

8. “Value innovation: the strategic logic of high growth”. W C Kim and R Mauborgne, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10174449/. Accessed 13 May 2024.

9. “The Reference Wars: Encyclopedia Britannica’s Decline and Encarta’s Emergence”. HBR Publications (Shane M. Greenstein), https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=50951. Accessed 13 May 2024.

10. “COMPETITIVE INTELLIGENCE ADDS VALUE”. Rouach and Santi, https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/COMPETITIVE-INTELLIGENCE-ADDS-VALUE-Rouach-Santi/0154008ac27e19e6294ae0e1894eb260b7ba0152. Accessed 14 May 2024.

11. “Competitive Intelligence: Gathering, Analysing and Putting it to Work”. Christopher Murphy, https://www.amazon.com/Competitive-Intelligence-Gathering-Christopher-2005-10-28/dp/B01JXQE0XO. Accessed 14 May 2024.

12. “Value Chain Analysis”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/value-chain-analysis/. Accessed 16 May 2024.

13. “SWOT Analysis – How to Do It Properly”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/swot-analysis-how-to-do-it/. Accessed 18 May 2024.

14. “Porter’s Five Forces”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/porters-five-forces/. Accessed 18 May 2024.

15. “The Value Net Model”. CIO Wiki, https://cio-wiki.org/wiki/The_Value_Net_Model. Accessed 18 May 2024.

16. “Porter’s four corners model”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Porter%27s_four_corners_model#. Accessed 18 May 2024.

17. “Supply Chain Analysis”. Sustainability Methods Wiki, https://sustainabilitymethods.org/index.php/Supply_Chain_Analysis. Accessed 18 May 2024.

18. “Customer Segmentation”. Bain, https://www.bain.com/insights/management-tools-customer-segmentation/. Accessed 18 May 2024.

19. “PEST & PESTEL Analysis”. Strategic Management Inisght, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/pest-pestel-analysis/. Accessed 18 May 2024.

20. “STEEP analysis”. CEPpedia Management Online, https://ceopedia.org/index.php/STEEP_analysis. Accessed 18 May 2024.

21. “Statement of Louis J. Freeh (Director FBI 1996)”. 1996 Congressional Hearings on Intelligence and Security, https://irp.fas.org/congress/1996_hr/s960228f.htm. Accessed 16 May 2024.

22. “Economic Espionage Act of 1996”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economic_Espionage_Act_of_1996. Accessed 16 May 2024.

23. “INTELLIGENCE ETHICS & INTEGRITY”. SCIP, https://www.scip.org/page/Ethical-Intelligence. Accessed 19 May 2024.

24. “The Intelligence Cycle”. CIA, http://www.ossh.com/cia/intelligence/intelligence_cycle.html. Accessed 19 May 2024.

25. “Managing market intelligence: an Asian marketing research perspective”. Thomas Tsu Wee Tan, Zafar U. Ahmed , https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/02634509910293124/full/html. Accessed 16 May 2024.

26. “List of national and international statistical services”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_national_and_international_statistical_services. Accessed 17 May 2024.

27. “Statistical Review of World Energy”. BP, https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy.html. Accessed 17 May 2024.

28. “The McKinsey Insights Store”. McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/insights-store. Accessed 17 May 2024.

29. “Strategic and Competitive Analysis: Methods and Techniques for Analyzing Business Competition”. Dr Craig Fleisher and Babette Bensoussan, https://www.amazon.com/Strategic-Competitive-Analysis-Techniques-Competition/dp/0130888524. Accessed 19 May 2024.