This article is a comprehensive exploration of the Blue Ocean Strategy that provides organizations with the frameworks and analytical tools to create and capture uncontested markets and unlock vast growth opportunities.

The term Blue Ocean Strategy (BOS) was first coined by Professors Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, who set out to understand what it takes in a competitive, global environment for business to not just to cope and survive but thrive.

Over three decades of their combined research culminated in the book called “Blue Ocean Strategy”, first published in 2005.

By definition, “Blue Ocean Strategy is the simultaneous pursuit of differentiation and low cost to open up a new market space and create new demand. It is about creating and capturing uncontested market space, thereby making the competition irrelevant. It is based on the view that market boundaries and industry structure are not a given and can be reconstructed by the actions and beliefs of industry players.”[1]

What is Blue Ocean Strategy

What are oceans?

Businesses operate in two kinds of market space called oceans – Red and Blue.

Red oceans denote the known market space in which all industries currently operate. This is where industry boundaries are defined and accepted, and competitive rules are set. Companies try to outperform rivals to grab a greater share of existing demand.

This market space is crowded with competition and prospects for profits and growth are limited. Products are commoditized, and cut-throat competition turns the ocean “bloody” – hence the word Red.

Blue Oceans, in contrast, denote the unknown market space – all the industries that are not currently in existence. This is an untapped area where demand is yet to be created and opportunities for highly profitable growth exist.

In blue oceans, competition is irrelevant as the rules of the game are waiting to be set. Any business that enters this space can address the market without competition.

How effective is the blue ocean strategy?

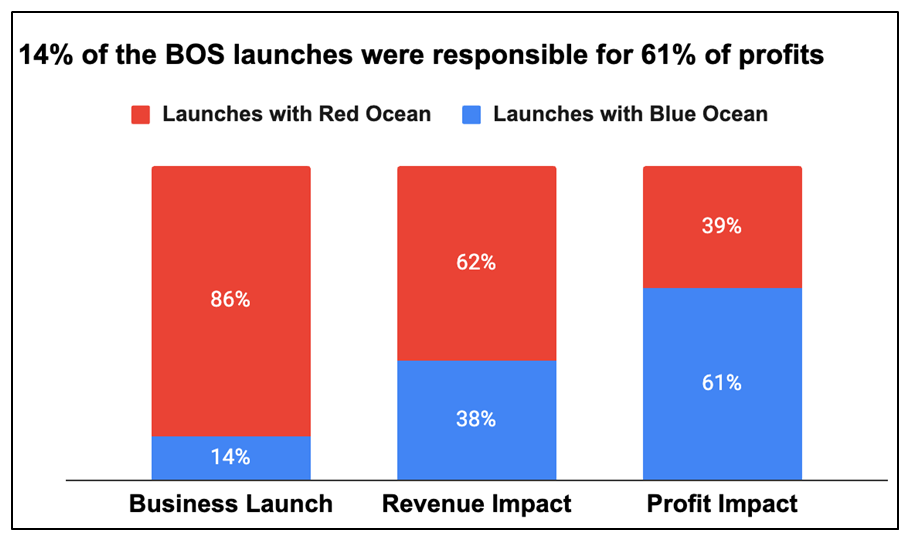

Professors Kim and Mauborgne, in their study spanning over three decades, quantified the impact of creating blue oceans on a company’s growth in both revenues and profits.

Their analysis covering 108 companies showed that 14% of the launches that aimed at creating blue oceans contributed to 38% of the revenue and 61% of the total profits.

Netflix as an example of BOS

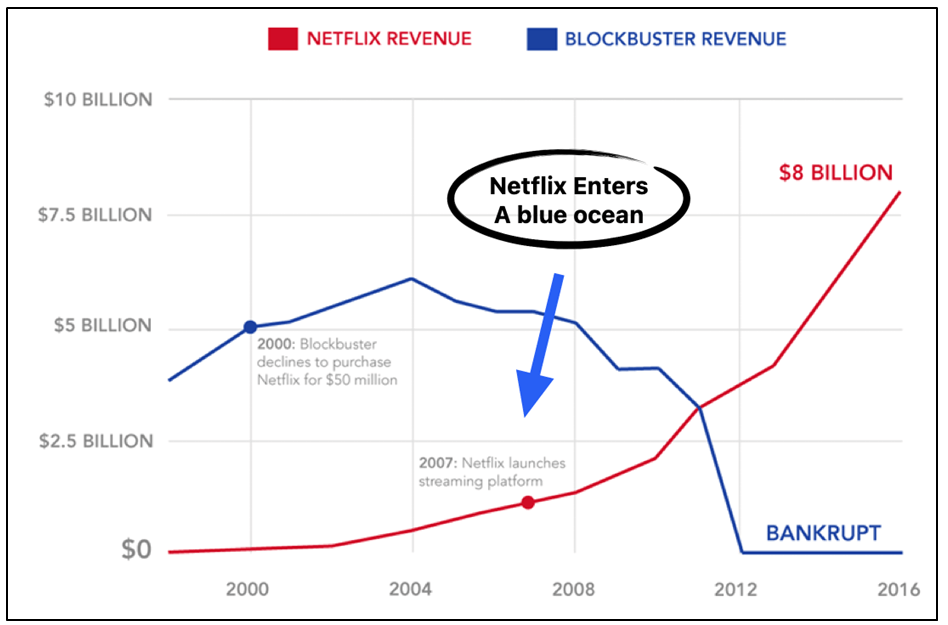

Blue ocean examples show around us all the time. Consider Netflix’s initial years. In an age where streaming movies was unheard of, Netflix entered a blue ocean by offering just that. It was able to create a new market space for itself by going beyond the conventional DVD rental market (red ocean).

By simultaneously offering low prices and the convenience of streaming with a vast content library, Netflix quickly become the dominant player in an uncontested market space. By the time competition followed, it was already a dominant player with an established name.

In contrast, Blockbuster – Netflix’s primary competitor swam too long in the red ocean (DVD rental market) and eventually headed towards bankruptcy.

A history of blue oceans

Though BOS is a new term, it has been a feature of business for a very long time. A hundred years ago, some of the most basic industries of today didn’t exist. Many of these started as blue ocean strategic move at some point before the boundaries disappeared and competition took over.

Ford’s Model T, introduced in 1908, is a classic example of a market-creating blue ocean strategic move that challenged the conventions of the automotive industry.

Same can be said about the future. As industries continuously evolve, operations improve, markets expand, and players come and go. In future, many of the industries unknown today will come into existence. These are the blue oceans waiting to be explored.

Why is BOS more important than ever?

Accelerated technological advances substantially improve industrial productivity. While suppliers can produce an unprecedented array of products and services, limited demand raises the bar for competition.

As globalization shrinks trade barriers between nations and regions, information on products and prices become instantly available. This breaks down niche markets that were once havens for monopoly. As brands tend to become more and more similar, consumers increasingly select based on price.

The business environment in which most strategy and management approaches of the twentieth century evolved is increasingly disappearing. As red oceans become increasingly bloody, businesses will need to focus on blue ocean strategies than competing within the saturated existing markets.

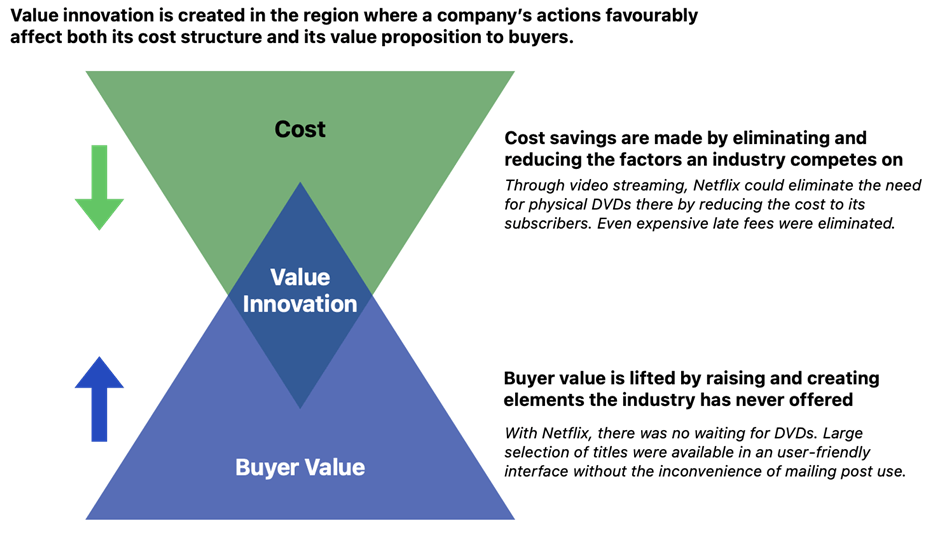

Value innovation – cornerstone of BOS

Traditionally, companies choose to either differentiate their products or services from the competition (by offering higher quality, more features, or better customer service) or to compete on price. This is known as the value-cost trade-off.

Value innovation challenges this convention by creating a new value curve that offers both higher value and lower costs than the competition.

By the simultaneous pursuit of differentiation and low cost, Value Innovation creates a leap in value for both buyers and the company.

Red and Blue Ocean – the key differences

Competition-based red ocean strategy assumes that an industry’s structural conditions are given and that firms are forced to compete within them.

Blue Ocean’s Value Innovation-based approach assumes that market boundaries and industry structure are not given and can be reconstructed by the actions and beliefs of industry players.

| Red Ocean Strategy | Blue Ocean Strategy |

|---|---|

| Compete in existing market space | Create uncontested market space |

| Beat the competition | Make the competition irrelevant |

| Exploit existing demand | Create and capture new demand |

| Make the value/cost trade-off | Break the value/cost trade-off |

| Align the whole system of a company’s activities with its strategic choice of differentiation or low cost | Align the whole system of a company’s activities with its strategic choice of differentiation and low cost |

Analytical Tools And Frameworks

The Strategy Canvas

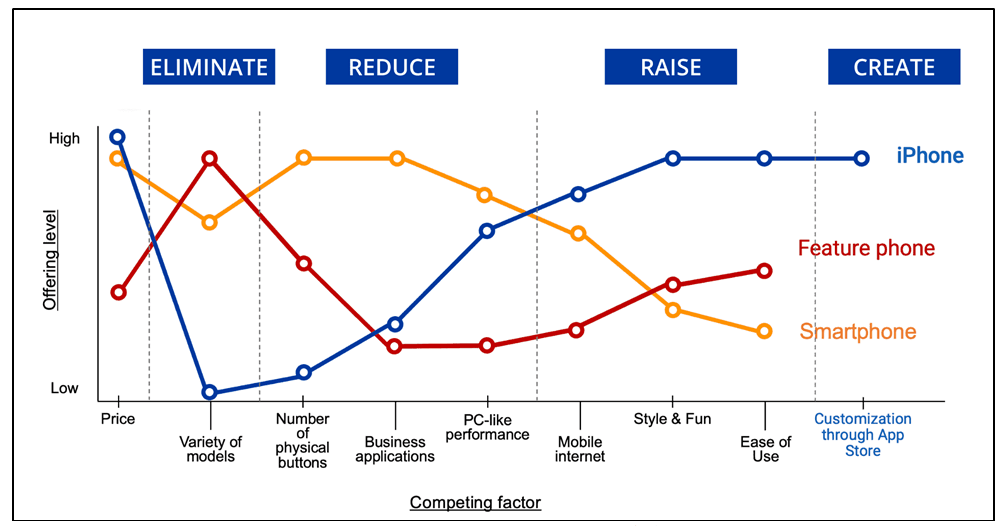

Strategy Canvas is a one-page visual analytic that depicts the way an organization configures its offering to buyers in relation to those of its competitors.

It communicates four key elements for a given business:

- The factors of competition

- The offering level buyers receive across these factors,

- Business’s strategic profiles and cost structures

- Competitors’ strategic profiles and cost structures

The Strategy Canvas of Apple’s iPhone from the early 2000s (in the figure below) shows the state of play in the handset industry (at the time). The horizontal axis shows key competitive factors the handset phone industry competed on.

In the Strategy canvas, it can be seen how Apple’s value curve differed from its competitors.

Red ocean players follow a similar profile competing on the established norms while blue ocean players stand out by creating new value areas for their customers.

The early iPhone combined PC-like performance with internet connectivity in a stylish design. It was easy to use and did not confuse buyers with too many buttons or models. It offered value in the areas the buyer cared about most and hence commanded a higher price.

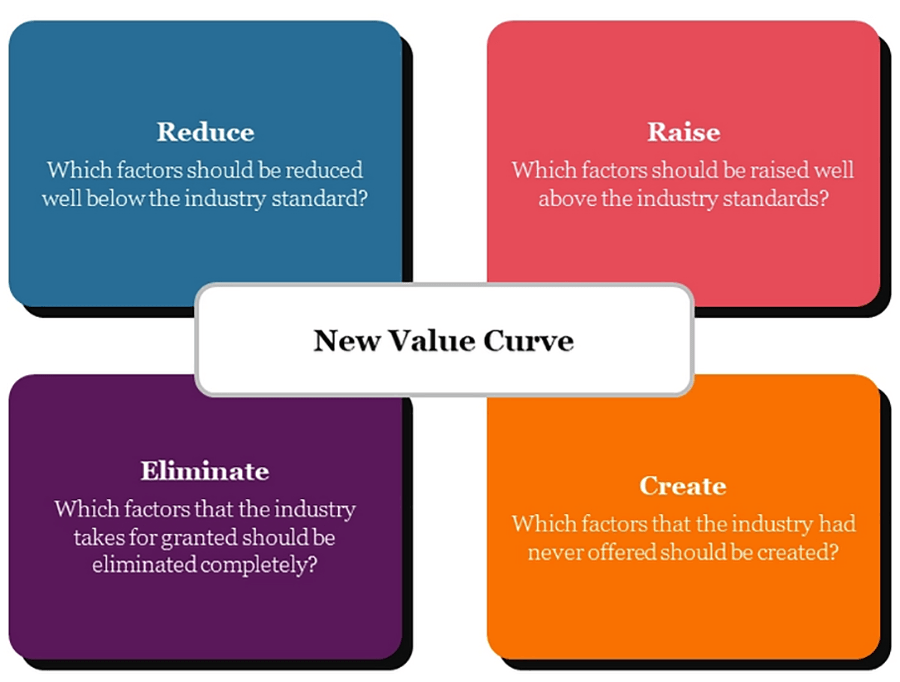

Four Actions Framework

Having developed the strategy canvas, a business can use the four actions framework to challenge its strategic logic and business model.

This framework is used to reconstruct buyer value elements in crafting a new value curve or strategic profile. It poses four key questions, shown below and challenges an industry’s strategic logic.

Eliminate: This question forces to consider eliminating factors that companies in the industry have long competed on. Often, these are factors taken for granted even though they no longer offer value. Sometimes there is a fundamental change in buyer’s value perception, but companies focused on benchmarking each other fail to notice the change.

Reduce: This question forces to determine whether products or services have been overdesigned in the race to match and beat the competition. Are companies overserving customers in areas they do not care about and increasing costs for little to no gain?

Raise: The third question pushes to uncover and eliminate the compromises customers are forced to make because of the way the industry is set up.

Create: This question helps to discover entirely new sources of value for buyers and create new demand and shift the strategic pricing of the industry. (Until the company Novo Nordisk invented NovoPen, administering insulin required a visit to the doctor)

By pursuing the first two questions (eliminate and reduce), companies gain insight into how to drop cost structure vis-à-vis competitors while the last two questions (raise and create) provide insight into how to lift buyer value and create new demand.

Eliminate-Reduce-Raise-Create grid

Eliminate-Reduce-Raise-Create (ERRC) grid is a supplementary analytic to the Four Actions Framework that pushes companies not only to ask four questions in the framework but also to act on each to create a new value curve. It offers four immediate benefits:

- It pushes to simultaneously pursue differentiation and low costs to break the value-cost trade-off.

- It immediately flags companies that are focused only on raising and creating and thereby lifting their cost structure and often overengineering products and services.

- It is easily understood by managers at any level, creating a high level of engagement in its application.

- It drives companies to robustly scrutinize every factor the industry competes on, thus discovering the range of implicit assumptions made unconsciously in competing.

An example of the Eliminate-Reduce-Raise-Create grid for Netflix’s early days when DVD rental was the norm:

| Eliminate | Raise |

| – Visit physical video rental stores. – Limitation in content selection due to shelf space and distribution costs. – Pay-per-DVD pricing model. | – Value of content accessibility – vast library of movies and tv shows. – Quality of content. – Convenience and flexibility of viewing. |

| Reduce | Create |

| – Cost of and time-to video consumption. – Late fees, travel expenses, and the need to physically return DVDs. – Physical media inventory management. – Advertisements and interruptions. | – Personalized user experience – recommendations. – Interactive user interface. – Original content production – Exclusivity. |

Characteristics of a Good Strategy

A strategy formulated using the tools discussed thus far should exhibit three characteristics – Focus, Divergence, and a Compelling Tagline. These three criteria serve as an initial litmus test of the commercial viability of blue ocean ideas.

Focus: Every great strategy must have focus and a company’s value curve should clearly show it.

For example, Southwest Airlines emphasize only three factors: friendly service, speed, and frequent point-to-point departures. By maintaining its focus, it doesn’t make unwanted investments in meals, lounges, and seating choices and keeps its prices competitive.

Divergence: On a strategic canvas, the value curves of blue ocean strategies must stand apart.

For example, Southwest pioneered point-to-point travel between midsize cities in an industry that mainly operated through hub-and-spoke model.

Compelling Tagline: A good strategy must have a clear-cut and compelling tagline that not only delivers a clear message but also advertises an offering truthfully.

For Southwest Airline, it could be – “The speed of a plane at the price of a car – whenever you need it.”. A regular airline with a conventional offering cannot come up with such a tagline unless there is focus and divergence.

Formulating Blue Ocean Strategy

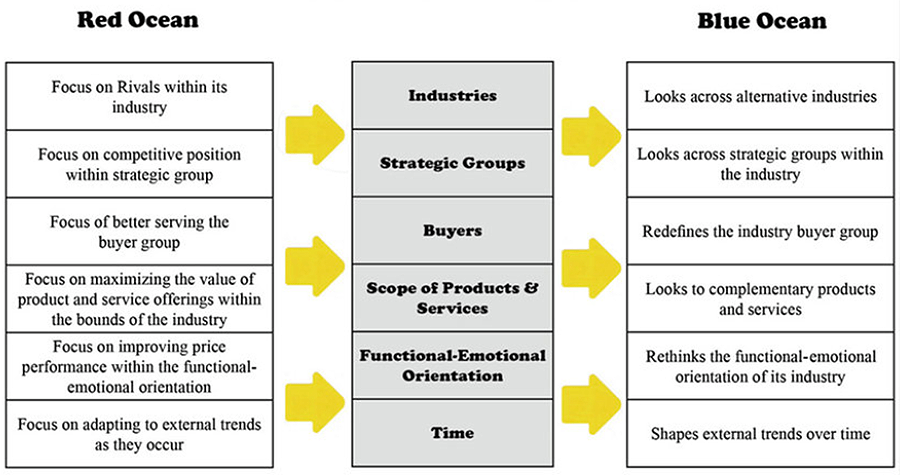

The six-path framework to reconstruct market boundaries

Blue Ocean Strategy is about reconstructing market boundaries to break from the competition and create blue oceans. The challenge is to successfully identify, out of the haystack of possibilities that exist, commercially compelling blue ocean opportunities.

There are six basic approaches to remaking market boundaries – called the six paths framework. They are:

Path 1: Look at alternative industries:

Company competes not only with the other firms in its own industry but also with companies in those other industries that produce alternative products or services. Alternatives are broader than substitutes and include products and services that have different forms but offer the same functionality or core utility.

For example, to address their financial planning, customers could buy a financial software package, hire a professional, use a mobile app or simply use pencil and paper. Each of these have very different forms but serve the same function.

Path 2: Look across strategic groups within industries:

Strategic groups refer to a group of companies within an industry that pursue a similar strategy. Fundamental differences among industry players are captured by only a small number of strategic groups.

For example, in the US fitness industry of 1995, there were only two kinds of health clubs.

First were high-end clubs that offered both men and women a full range of exercise and sporting options at high prices. Second were low-cost home exercise programs that offered exercise videos, books, and magazines.

This changed when Curves[5], a women-focused fitness company introduced reasonably priced clubs and built a blue ocean market for itself.

Path 3: Look Across the Chain of Buyers

Challenging an industry’s conventional wisdom about which buyer group to target can lead to the discovery of a new blue ocean.

For example, Novo Nordisk[6], the Danish insulin producer created a blue ocean in the insulin industry by shifting their buyers from doctors to the patients themselves. With the creation of its NovoPen, the first user-friendly insulin delivery solution, patient could easily self-administer insulin safely.

Similarly, Bloomberg[7] found a blue ocean by shifting its focus from the IT managers to whom it sold trading software to actual traders and analysts.

Path 4: Look Across Complementary Product and Service Offerings

Products and services are seldom used in a vacuum. In most cases, other products and services affect their perceived value. But in most industries, rivals tend to stay within the bounds of their industry’s product and service offerings.

For example, in the airline industry, ground transportation time after flight can affect customer’s choice of whether to fly or to drive.

By thinking in terms of solving the major pain points in customers’ total solution, there could be an opportunity to create a blue ocean.

Dyson, for example, leapfrogged the competition by eliminating the need for vacuum cleaner bags and all the cost and hassle of buying new bags[8].

Path 5: Look Across Functional or Emotional Appeal to Buyers

Some industries compete principally on price and function largely on calculations of utility – their appeal is rational. Other industries compete largely on feelings; their appeal is emotional.

Over time, functionally oriented industries become more functionally oriented and emotionally oriented industries become more emotionally oriented. When companies challenge this functional-emotional orientation of their industry, they often find blue oceans.

Japan’s QB House (Quick Beauty)[9] for example, did just that. When it started in 1996, the time it took for a haircut was over an hour due to a long process of ritualistic activities. This also led to higher prices, typically between 3,000 to 5,000 yen ($27 to $45).

QB recognized that many, especially working professionals, did not wish to waste an hour on haircut. By stripping away the emotional (ritualistic) elements, and staying focused on speed, it saw immense success for decades. Prices too dropped to 1,000 yen ($9).

Likewise, Starbucks[10] did the reverse and turned the commoditized coffee industry (rational) into an emotional experience. Customers now choose Starbucks to spend quality time and socialize over a good cup of coffee.

Path 6: Look Across Time

By looking across time from the value a market delivers today to the value it might deliver tomorrow, businesses can actively shape their future and enter a new blue ocean. Usually, these are driven by a discontinuity in technology, rise of a new lifestyle, or a change in regulatory or social environment.

For example, in the late 1990s, Apple observed the flood of illegal music on file sharing platforms like Napster.[11] With the technology allowing anyone to digitally download music free instead of paying $19 for an average CD at the time, the trend toward digital music was clear.

In response, Apple launched iTunes[12] which offered legal, easy-to-use, and flexible à la carte song downloads. With a collection of over two hundred thousand songs, consumers could download an individual song for as low as 99 cents or an entire album for $9.99. For Apple, this was a blue ocean that shaped consumer habits.

Likewise, using this path, CNN created the first real-time twenty-four-hour global news network based on the rising tide of globalization.

Summary of the Six Paths

The process of discovering and creating blue is a structured process of reordering market realities in a fundamentally new way. By reconstructing existing market elements across industry and market boundaries, businesses can free themselves from head-to-head competition in the red ocean.

Focus on the big picture, not the numbers

While most managers have a strong impression of how they and their competitors fare within their scope of their responsibility, they often fail to see the overall industry dynamics. BOS provides a four-step strategy visualization tool that serves to unlock people’s creativity.

Step 1: Visual Awakening

This involves comparing a business with its competitors by drawing “as is” strategy canvas and finding where the strategy needs to change. Asking executives to draw the value curve of their company’s strategy brings home the need for change. It serves as a forceful wake-up call for companies to challenge their existing strategies.

Step 2: Visual Exploration

This step is about going into the field to explore the six paths to create blue oceans. By observing the distinctive advantages of alternative products and services, businesses can realize what factors to eliminate, create, or change.

Sending a team into the field puts managers face-to-face with what they must make sense of and helps realize how customers use or don’t use their products or services. A company must avoid outsourcing this step or substituting it with intelligence reports.

Step 3: Visual Strategy Fair

This step involves drawing the “to be” strategy canvas based on insights from field observations and getting feedback on alternative strategy canvases from customers, competitors’ customers, and noncustomers. This feedback will then be used to build the best “to be” future strategy.

Step 4: Visual Communication

This last step involves distributing the before-and-after strategic profiles on one page for easy comparison. The new strategic profile should become the reference point for all investment decisions. It is important to support only those projects and operational moves that allow a business to close the gaps to actualize the new strategy.

The Pioneer-Migrator-Settler (PMS) Map

Assessing a company’s portfolio offerings according to the innovative value they offer to buyers lets a company see how strategically vulnerable or healthy its portfolio is. The pioneer-migrator-setter map helps achieve this by dividing a company’s offerings into three segments: Pioneers, Migrators, and Settlers.

Pioneers are businesses that offer unprecedented value. These are the blue ocean offerings that are the most powerful sources of profitable growth. These businesses have a mass following of customers and their value curve diverges from the competition on the strategy canvas.

Settlers are the other extreme businesses whose value curves conform to the basic shape of the industry’s. As me-too businesses, Settlers will not generally contribute much to a company’s future growth. They are stuck within the red ocean.

Migrators lie somewhere in between. These businesses extend the industry’s curve by giving customers more for less, but they don’t alter its basic shape. These businesses offer improved value, but not innovative value. These are businesses whose strategies fall on the margin between red oceans and blue oceans.

If a company’s current portfolio and planned offerings consist mainly of settlers, the company has a low growth trajectory, is largely confined to red oceans. If it consists of a lot of migrators, reasonable growth can be expected.

Companies must strive to push their businesses toward pioneers.

Reach Beyond Existing Demand

Challenging the conventional strategies

Maximizing the size of a newly created blue ocean requires reaching beyond the existing demand. This requires challenging the two conventional strategies:

(1) Focus on existing customers: Instead of concentrating on existing customers, companies need to look to noncustomers.

(2) Drive for finer segmentation to accommodate buyer differences: Instead of creating finer segmentations, companies must build on powerful commonalities around what customers value. That allows them to reach beyond existing demand to unlock a new mass of customers that did not exist before.

For example, when the US golf industry fought to win a greater share of existing customers, Callaway[13] created a blue ocean by asking why sports enthusiasts and people in the country club set had not taken up golf as a sport. It found that hitting the golf ball was perceived as too difficult with the small size golf club.

By offering a golf club with a large head, it converted noncustomers of the industry into customers. Even the existing customers, who took the norm for granted were pleased with the new offering.

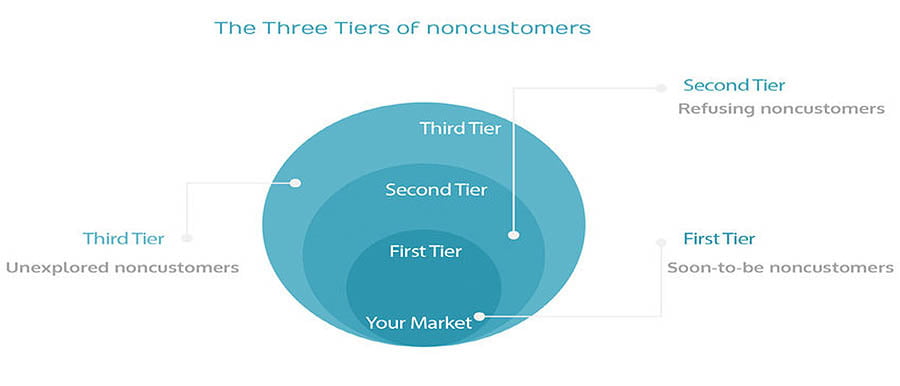

The three tiers of Noncustomers

Noncustomers fall under three categories.

Tier 1: “Soon-to-be” noncustomers who are on the edge of the market, waiting to jump ship. These are the closest to the current market. They sit on the edge of the market and are buyers who minimally purchase an industry’s offering out of necessity but are mentally noncustomers of the industry. They are waiting to jump ship and leave the industry as soon as the opportunity presents itself.

However, if offered a leap in value, not only would they stay, but also their frequency of purchases would multiply, unlocking enormous latent demand.

For example, Pret[14], a British fast-food chain (with focus on fresh food) expanded its blue ocean by tapping into the huge latent demand of tier-1 noncustomers who were professionals frequenting restaurants for lunch. The appeal of fresh food served in under 90 seconds and at a reasonable price captured the restaurant-goers’ attention who otherwise did not consider fast food.

Tier 2: “Refusing” noncustomers who consciously choose against the market. These are people who either do not use or cannot afford to use the current market offerings because they find the offerings unacceptable or beyond their means. But, harboring within these is an ocean of untapped demand waiting to be released.

For example, JCDecaux[15], a vendor of French outdoor advertising space pulled the mass of refusing noncustomers into its market by creating a new concept in outdoor advertising called “street furniture”. Up until then, the outdoor advertising industry was about billboards (usually installed on city outskirts) and transport advertisement that exposed people for a very short time to get influenced by advertisements.

JCDecaux realized this was the key reason the industry remained unpopular and small. It found that municipalities could offer stationary downtown locations, such as bus stops, where people tended to wait a few minutes and hence had time to read and be influenced. It introduced street furniture with integrated advertising panels that were offered free to municipalities including maintenance and upkeep. Mass of refusing noncustomers flocked towards JCDecaux and the idea took-off as a profitable medium of advertisement.

Tier 3: “Unexplored” noncustomers who are in markets distant from the one in question. These are the farthest from the market and have never thought of the current market’s offerings as an option.

Typically, these unexplored noncustomers have not been targeted or thought of as potential customers by any player in the industry. This can be because their needs and the business opportunities associated with them have somehow always been assumed to belong to other markets.

For example, for a very long time, tooth whitening was a service provided exclusively by dentists and not by oral care consumer-product companies.

While there is no hard-and-fast rule as to which tier of noncustomers a company should focus on and when, companies must focus on one that represents the biggest catchment and is close the capability to act on.

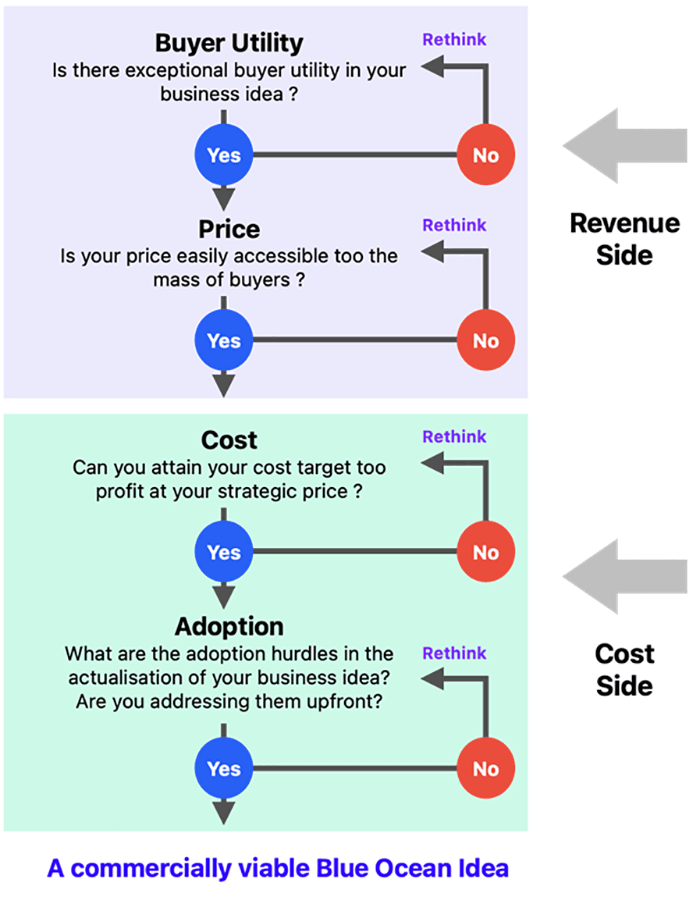

Getting the strategic sequence right

Buyer Utility, Price, Cost, and Adoption

Companies need to build their blue ocean strategy in the sequence of buyer utility, price, cost, and adoption.

Buyer Utility is the starting point. Does the offering unlock exceptional utility? Is there a compelling reason for the target mass of people to buy it? Without this, there is no blue ocean potential to begin with. In this case, either park the idea, or rethink it until an affirmative answer is reached.

Arriving at the right strategic Price is the second step. A company does not want to rely solely on price to create demand. The key question here is this: Is the offering priced to attract the mass of target buyers so that they have a compelling reason and ability to pay? If it is not, they cannot buy it.

Together, these first two steps address the revenue side of a company’s business model.

Cost is the third step. Can the company produce its offering at the target cost and still earn a healthy profit margin?

Costs should not drive prices, nor should the utility be scaled down because high costs block the company’s ability to profit at the strategic price. If the target cost cannot be met, the company must either forgo the idea or innovate its business model to hit the target cost.

The last step is to address Adoption hurdles. What are the adoption hurdles in rolling out the idea? Are they addressed up front? Because blue ocean strategies represent a significant departure from red oceans, it is key to address adoption hurdles up front.

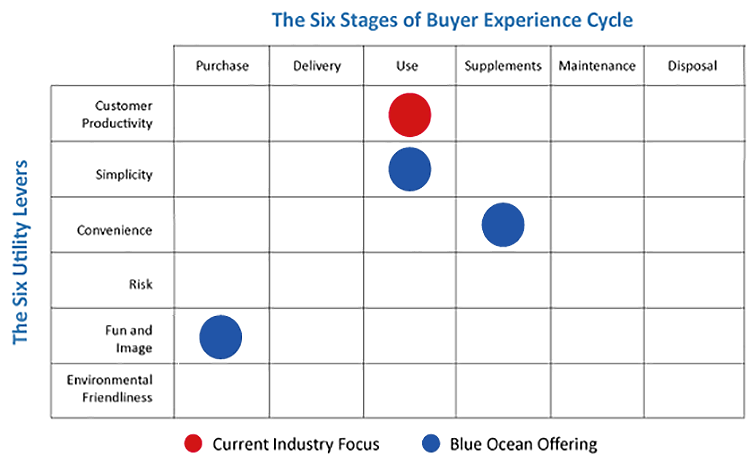

Buyer utility map

The buyer utility map helps to think from a demand-side perspective. It outlines all the levers companies can pull to deliver exceptional utility to buyers as well as the various experiences buyers can have with a product or service. This mindset helps managers identify the full range of utility spaces that a product or service can potentially fill.

It has two dimensions: The Buyer Experience Cycle (BEC) and the Utility levers.

The six stages of the buyer experience cycle

A buyer’s experience can usually be broken into a cycle of six stages, running sequentially from purchase to disposal. At each stage, managers can ask a set of questions to gauge the quality of buyers’ experience.

For example:

| Purchase | How long does it take to find the product? Is the place of purchase attractive and accessible? How secure is the transaction environment? How rapidly can the purchase be made? |

| Delivery | How long does it take to get the product delivered? How difficult is it to unpack and install the new product? Do buyers have to arrange the delivery themselves? |

| Use | Does the product require training or expert assistance? Is the product easy to store when not in use? How effective as the product features and functions? |

| Supplements | Do you need another product or service to make this product work? If so, how costly are they? How much time do they take? |

| Maintenance | Does the product require external maintenance? How easy is it to maintain and upgrade the product? What is the cost of maintenance? |

| Disposal | Does use of product create waste items? How easy is it to dispose of the product? Are there legal or environmental issues in disposing of the product safely? How costly is disposal? |

The six utility levers

Cutting across the stages of the buyer’s experience are six utility levers: Productivity, Simplicity, Convenience, Risk Reduction, Fun & Image, and Environment friendliness.

Together, these help companies explore ways to unlock exceptional utility for customers.

Simplicity, fun and image, and environmental friendliness are self-explanatory. A product must reduce a customer’s financial, physical, or credibility risks. It must also offer convenience by being easy to obtain, use, or dispose of.

The most used lever is that of customer productivity, in which an offering helps a customer do things faster or better. Companies must check whether their offering has removed the greatest blocks to utility across the entire buyer experience cycle for customers and noncustomers. The greatest blocks to utility often represent the greatest and most pressing opportunities to unlock exceptional value.

From exceptional utility to strategic pricing

To secure a strong revenue stream for its offering, a company must set the right strategic price. This step ensures that buyers not only will want to buy its offering but also will have a compelling ability to pay for it.

Companies can also take a reverse course, first testing the waters of a new product or service by targeting novelty-seeking, price-insensitive customers and drop prices later on to attract mainstream buyers. (Example: Tesla electric vehicles)

There are two reasons for this change.

First, companies discover that volume generates higher returns than it used to. For knowledge-intensive products (like software), companies bear most of their costs in product development than in manufacturing which makes volume the key.

A second reason is that to a buyer, the value of a product or service may be closely tied to the total number of people using it. Online auction / networking sites fall under this category.

If a company’s offering belongs to the category of knowledge-intensive products, the pricing must also consider the potential for free riding.

In some cases, free riding can be protected by the nature of the goods/services (difficult to replicate, investment heavy etc.) or by the legal systems like patent protection, but most business innovations cannot eliminate free riding. Strategic price must not only attract buyers in large numbers but also help to retain them. Earning a reputation quickly is also a key. Companies must therefore start with an offer that buyers can’t refuse and keep it that way to discourage any free-riding imitations.

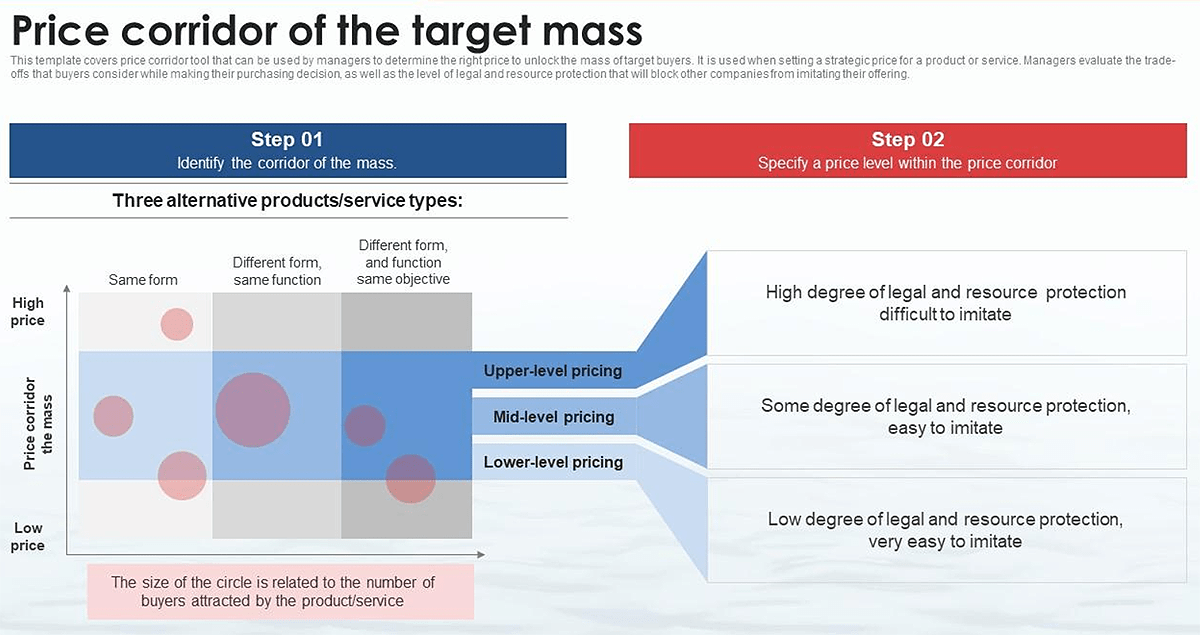

Setting the strategic price

Price corridor of the target mass is a tool managers used to determine the right price to unlock the mass of target buyers. When setting a strategic price for a product or service, it is important to evaluate the trade-offs that buyers consider when making their purchasing decision, as well as the level of legal and resource protection that will block other companies from imitating its offering.

Source: SlideTeam.net[16]

Step 1: Identify the price corridor of the target mass.

In setting a price, companies look first at the products and services that most closely resemble their idea in terms of form. While looking at other products and services within own industries is a necessary exercise, by itself, it is not sufficient. Customers will compare the new product or service with a host of very different-looking products and services offered outside the group of traditional competitors.

A good way to look outside industry boundaries is to list products and services that fall into two categories:

Category 1: Those that take different forms but perform the same function. For example, the horse-drawn carriage had the same core utility as the car: transportation for individuals and families. But it had a very different form: a live animal versus a machine.

Category 2: Those that take different forms and functions but share the same overarching objective. For example, bars and restaurants have few physical features in common with a theater but might compete for customers’ time.

Step 2: Specify a level within the price corridor.

How high a price a company can set within the corridor without inviting competition depends on two principal factors.

The degree to which the product or service is protected legally through patents or copyrights and the degree to which the company owns some exclusive asset or core capability, such as an expensive production plant or unique design competence that can block imitation.

Companies with their offerings falling under this category can use upper-boundary strategic pricing to attract the mass of target buyers. As for companies that have no such protection, lower-boundary strategic pricing becomes necessary.

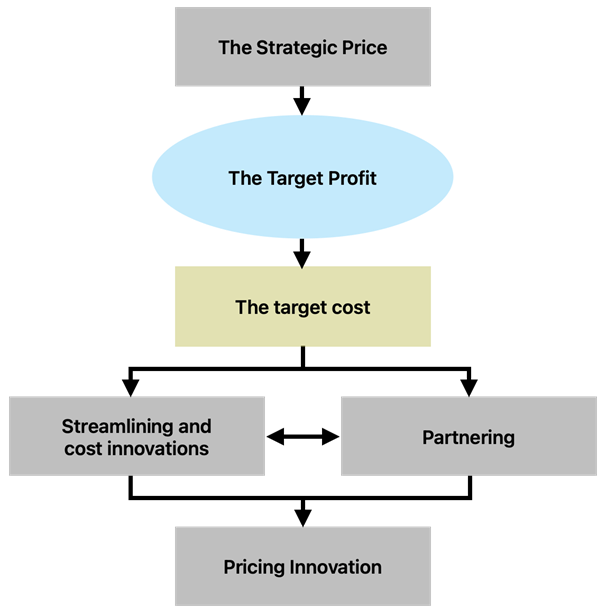

From strategic pricing to target costing

To maximize the profit potential of a blue ocean idea, a company must start with the strategic price and then deduct its desired profit margin from the price to arrive at the target cost.

This price-minus costing, and not cost-plus pricing, is critical to arrive at a cost structure that is both profitable and hard for potential followers to match. This also forces a company to strip out unnecessary costs.

To achieve the cost target, companies have three principal levers:

First – streamline operations and introduce cost innovations from manufacturing to distribution.

The second – partnering with other companies to secure needed capabilities by leveraging other companies’ expertise and economies of scale.

The third – achieve the desired profit margin without compromising on the strategic price. NetJets, for example, changed the pricing model of jets from complete ownership to time-share based to profitably deliver on its strategic price. Freemium is another pricing strategy that companies use (typically for a digital offering such as software, media, games, or web services) where a service is provided free of charge to pull in the target mass, but a premium is charged for proprietary features, functionality, or virtual goods.

The profit model of the blue ocean strategy

From Utility, Price, and Cost to Adoption

Employees

Before companies go public with an idea and set out to implement it, making a concerted effort to communicate to employees is crucial. It is important that employees are aware of the threats posed by the execution of the idea.

When Netflix was transitioning from a DVD-by-mail business to providing video streaming, great emphasis was put on engaging employees by explaining the necessity of the shift, what it means to them, and preparing them for the change.

Business Partners

Potentially even more damaging than employee disaffection is the resistance of partners who fear that their revenue streams or market positions are threatened by a new business idea. Openly discussing the issues with partners and convincing them to see the value in the shift is equally crucial to ensure business co-operation.

The General Public

Opposition to a new business idea can also spread to the public, especially if the idea threatens established social or political norms. The effects can be dire. For example, when Monsanto[17], (An agrochemical and agricultural biotechnology corporation, now part of Bayer) introduced genetically modified crop seeds, debate on genetically modified foods intensified around the globe, with Monsanto often at the heart of the attacks.

Executing Blue Ocean Strategy

Compared to red ocean, blue ocean strategy represents a significant departure from the status quo. It hinges on a shift from convergence to divergence in value curves at lower costs thus raising the bar of execution challenge.

Overcoming organization hurdles

The four organizational hurdles to strategy execution

Cognitive hurdle: The challenge of waking employees up to the need for a strategic shift. While red oceans may not be the paths to future profitable growth, they feel comfortable and have served organizations well thus far. Hence rocking the boat becomes difficult.

Resource hurdle: The greater the shift in strategy, the greater is the need for resources to execute it. But resources are often cut and not raised.

Motivation hurdle: How to motivate key players to move fast and tenaciously to carry out a break from the status quo? Sometimes it takes years, and companies don’t have that time.

Political hurdles: Getting shot down before you stand up.

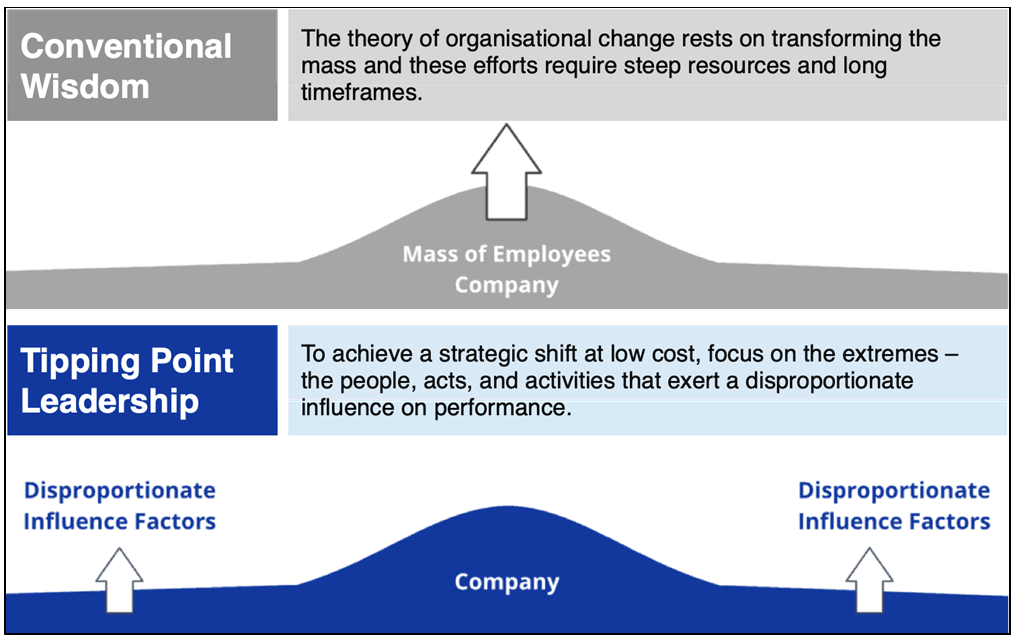

Use of tipping point leadership

Tipping point leadership builds on the rarely exploited corporate reality that in every organization, there are people, acts, and activities that exercise a disproportionate influence on performance. The key is conserving resources and cutting time by focusing on identifying and then leveraging the factors of disproportionate influence in an organization.

Breaking the Hurdles:

| The hurdle | Strategies to overcome |

|---|---|

| Cognitive Hurdle – An organization wedded to the status quo | – Make people see and experience the harsh reality firsthand. – Leverage the fact that negative stimuli changes attitudes and behavior. – Make people meet disgruntled customers. |

| Resource Hurdle – limitation of resources | – Instead of focusing on getting more resources, focus on multiplying the value of the existing resources. – Identify hotspots – activities with low resource input but high-performance gains. – Identify cold spots – activities with high resource input but low performance gains. – Redirect resources from cold spots to hot spots (Engage in horse-trading) |

| Motivational Hurdle – Motivating the mass of employees | Zoom in on Kingpins – Key influencers in the organization who are natural leaders. – Place Kingpins in a Fishbowl – Let others watch their performance. – Raise the stakes of inaction for everyone to see. Recognize high achievers. Develop an intense performance culture. – Use Atomization – breakdown the tasks into bite-size “atoms” that employees at different levels could relate to. |

| Political Hurdle – powerful vested interests resisting impending changes. | – Leverage Angels – Those who have the most to gain from the strategy. – Silence the Devils – Those who have most to lose. – Get a consigliere – A politically adept but highly respected insider who knows in advance all the land mines, including who will fight you and who will support the cause. |

Build Execution into Strategy

A company needs to invoke the most fundamental base of action – the attitudes and behavior of its people. This creates a culture of trust and commitment that motivates people to execute the agreed strategy not just in letter, but in spirit. In blue ocean, this challenge is heightened.

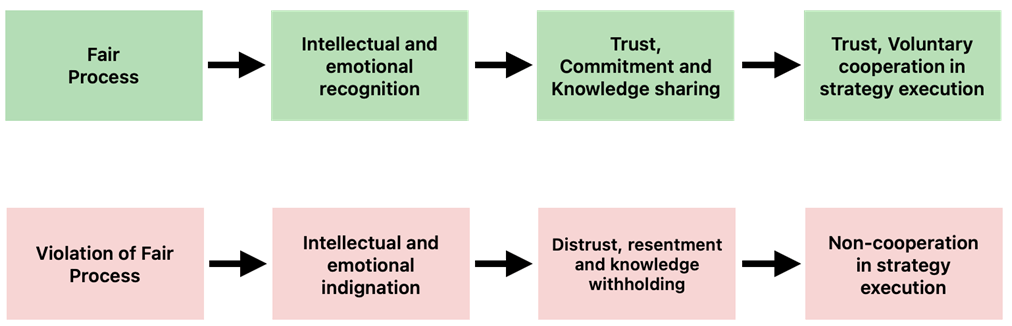

Fair Process

Fair process is a key variable that distinguishes successful blue ocean strategic moves from those that failed. The presence or absence of a fair process can make or break a company’s best execution efforts.

Fair process builds execution into strategy by creating people’s buy-in up front. By exercising fair process in the strategy formulation phase, people develop trust that a level playing field exists, inspiring voluntary cooperation during the execution phase.

Three mutually reinforcing elements define the fair process:

Engagement: Involve individuals in the strategic decisions that affect them by asking for their input and allow them to refute the merits of one another’s ideas and assumptions. This communicates management’s respect for individuals and their ideas.

Explanation: Everyone involved and affected should understand why final strategic decisions are made as they are. This allows employees to trust managers’ intentions even if their own ideas have been rejected. It also serves as a powerful feedback loop that enhances learning.

Clarity of expectation: After a strategy is set, managers must clearly state the new rules of the game. Employees should know up front what standards they will be judged by and the penalties for failure. It is important to clearly communicate the goals of the new strategy, its targets, and milestones and who is responsible for what.

The consequences of the presence and absence of fair process:

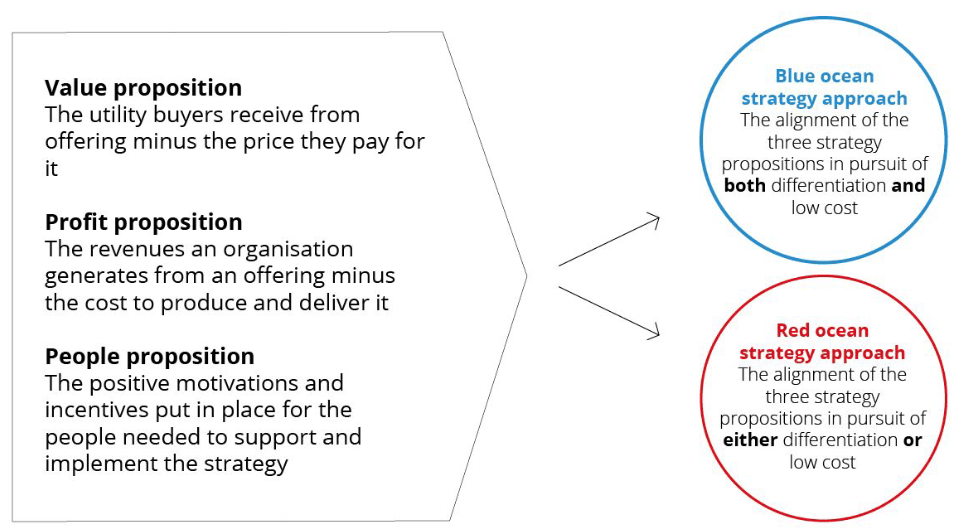

Aligning Value, Profit, and People Propositions

At the highest level, there are three propositions essential to the success of strategy: the value proposition, the profit proposition, and the people proposition.

Figure below explains each of these propositions and how they play out differently in a blue ocean strategy vs a red ocean strategy.

Source: http://kimboal.ba.ttu.edu[19]

In red ocean strategy, the three strategy propositions need to be aligned with the distinctive choice of pursuing either differentiation or low cost within given industry conditions. Here, differentiation and low cost represent alternative strategic positions in an industry.

In a blue ocean strategy, an organization achieves high performance when all three strategy propositions pursue both differentiation and low cost. It is this alignment in support of differentiation andlow cost is critical to success and sustainability.

For example, consider Napster and Apple’s iTunes in the digital music industry. Both started out to create and capture uncontested market space with digital music. Napster had a clear first-mover advantage, pulled in over 80 million registered users, and was generally loved for its value proposition, but its strategy ultimately failed. It had no sustainability.

In contrast, iTunes achieved sustainable success and both dominated and grew the blue ocean of digital music.

What was lacking in Napster was its failure to align external people – its partners to support the compelling value it unlocked. When the record labels approached Napster to work out a revenue-sharing model, Napster balked while Apple partnered with major music companies.

Renew Blue Oceans

Creating a blue ocean is a dynamic process. Once a company creates a blue ocean and its powerful performance consequences are known, imitators appear on the horizon. If the imitators succeed and expand the blue ocean, competition intensifies and eventually turns the ocean red.

Hence renewal is key to ensure that the creation of blue oceans is not a one-off occurrence but is institutionalized as a repeatable process in an organization.

A blue ocean strategy brings with it considerable barriers to imitation that effectively prolong sustainability. These are:

| The alignment barrier | – The alignment of the three strategy propositions – value, profit, and people into an integral system around both differentiation and low-cost builds sustainability and is a formidable barrier to imitation. |

| The cognitive and organizational barrier | – A value innovation move does not make sense based on conventional strategic logic. – Imitation requires organizational changes that the politics of few companies can bear in the short term. |

| The brand barrier | – Existing brand image conflict prevents companies from imitating a blue ocean strategy. – Companies that value-innovate build brand buzz and a loyal customer base that shun imitators. |

| The economic and legal barrier | – Natural monopoly – market cannot support a second player. – High volume generated by a value innovation leads to rapid cost advantages, placing potential imitators at a disadvantage. – Network externalities also block companies from easily and credibly imitating a blue ocean strategy. – Patents or legal permits also block imitation as they grant a value innovator an exclusive legal right. |

Eventually, almost every blue ocean strategy will be imitated. If the company is obsessed with hanging on to existing market share, it tends to fall into the trap of focusing on the competition, and not the buyer. With time, the shape of its strategic canvas will begin to converge with those of the competition.

To avoid this trap, monitoring value curves on the strategy canvas is essential. These value curves signals when to value-innovate and when not to. It alerts a company to reach out for another blue ocean when its value curve begins to converge.

For more details on Blue Ocean Strategy, refer the author’s published book and official website. An online course is also available on the official website.

Sources

1. “WHAT IS BLUE OCEAN STRATEGY?”. Chan Kim & Renée Mauborgne, https://www.blueoceanstrategy.com/what-is-blue-ocean-strategy/. Accessed 03 Jun 2023

2. “ABOUT THE BOOK: BLUE OCEAN STRATEGY”. Blueoceanstrategy.com, https://www.blueoceanstrategy.com/books/blue-ocean-strategy-book/. Accessed 03 Jun 2023

3. “Winning the Customer Journey Battle: Netflix vs Blockbuster Case Study”. Strategyjourney.com, https://strategyjourney.com/winning-the-customer-journey-battle-netflix-vs-blockbuster-case-study/. Accessed 02 Jun 2023

4. “The Strategy Canvas of Apple iPhone”. Blueoceanstrategy.com, https://www.blueoceanstrategy.com/blog/strategy-canvas-examples/. Accessed 03 Jun 2023

5. “Women’s Health & Fitness Clubs”. Curves, https://www.curves.com/. Accessed 06 Jun 2023

6. “What we do”. Novonordisk, https://www.novonordisk.com/about/what-we-do.html. Accessed 06 Jun 2023

7. “Bloomberg Terminal”. Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/solution/bloomberg-terminal/. Accessed 06 Jun 2023

8. “vacuum-cleaners”. Dyson, https://www.dyson.com/vacuum-cleaners. Accessed 06 Jun 2023

9. “SERVICES”. QB House, https://qbhouseusa.com/. Accessed 06 Jun 2023

10. “Our Heritage”. Starbucks, https://www.starbucks.co.id/about-us/our-heritage. Accessed 06 Jun 2023

11. “Napster”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napster. Accessed 06 Jun 2023

12. “iTunes”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ITunes. Accessed 06 Jun 2023

13. “Homepage”. Callawaygolf, https://www.callawaygolf.com/. Accessed 07 Jun 2023

14. “About Pret”. Pret, https://www.pret.com/en-US/about-pret. Accessed 07 Jun 2023

15. “OUT-OF-HOME ADVERTISING”. Jcdecaux, https://www.jcdecaux.com/group/activities. Accessed 08 Jun 2023

16. “BUYER UTILITY MAP”. SlideTeam.net, https://www.slideteam.net/blue-ocean-strategy-price-corridor-of-the-target-mass-ppt-powerpoint-presentation-icon-guidelines.html. Accessed 07 Jun 2023

17. “Monsanto”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monsanto. Accessed 07 Jun 2023

18. “TIPPING POINT LEADERSHIP”. Blueoceanstrategy.com, https://www.blueoceanstrategy.com/tools/tipping-point-leadership/. Accessed 07 Jun 2023

19. “Align Value, Profit, and People Proposition”. Danielle Bodette, Cole Tacker, D’Vonta Hinton, Joey King, http://kimboal.ba.ttu.edu/MGT%204380%20Fall%2008/New_Folder2/Team2_10am_BOS_10222018.pdf. Accessed 07 Jun 2023