“Are you sure you have a strategy?” – was the title of the article in which Donald Hambrick and James Fredrickson introduced the “Strategy Diamond” – a management framework for strategy formulation.[1]

Companies use the term strategy in various contexts, such as service strategy, branding strategy, acquisition strategy, or marketing strategy. However, the specific outcomes or the constituents of these strategies are seldom defined precisely.

Through the strategy diamond framework, authors Hambrick & Fredrickson present a comprehensive and cohesive process of strategy formulation. The framework integrates key elements that must come together to form a strategy to achieve business objectives.

So, what is a strategy?

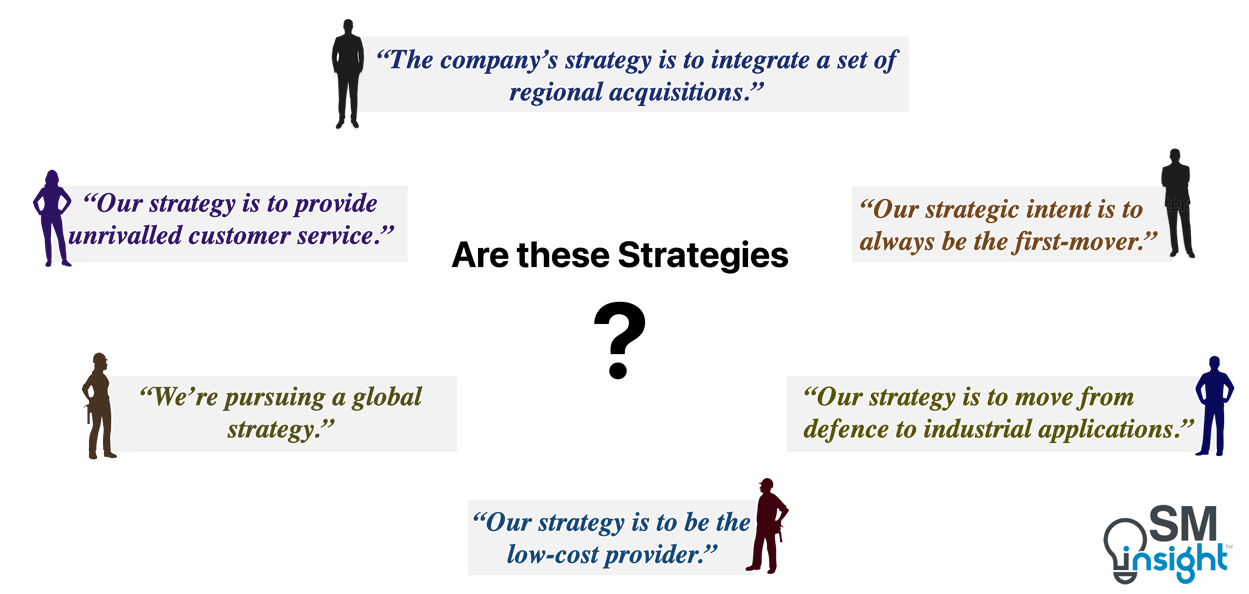

Strategy statements in the figure above are drawn from documents and announcements of several companies. They have only one thing in common – none of them is a strategy!

They represent strategic threads or mere elements of strategies. In insolation, they are not sufficient to help achieve business goals.

Strategy is derived from the Greek word “strategos”, or “the art of the general” and in the field of management, it serves just that goal – it must orchestrate the business while comprehensively addressing multiple factors.

A business strategy is a central, integrated, externally oriented concept of how the business will achieve its objectives. Without a strategy, time and resources are easily wasted on piecemeal, disparate activities without meaningful results.

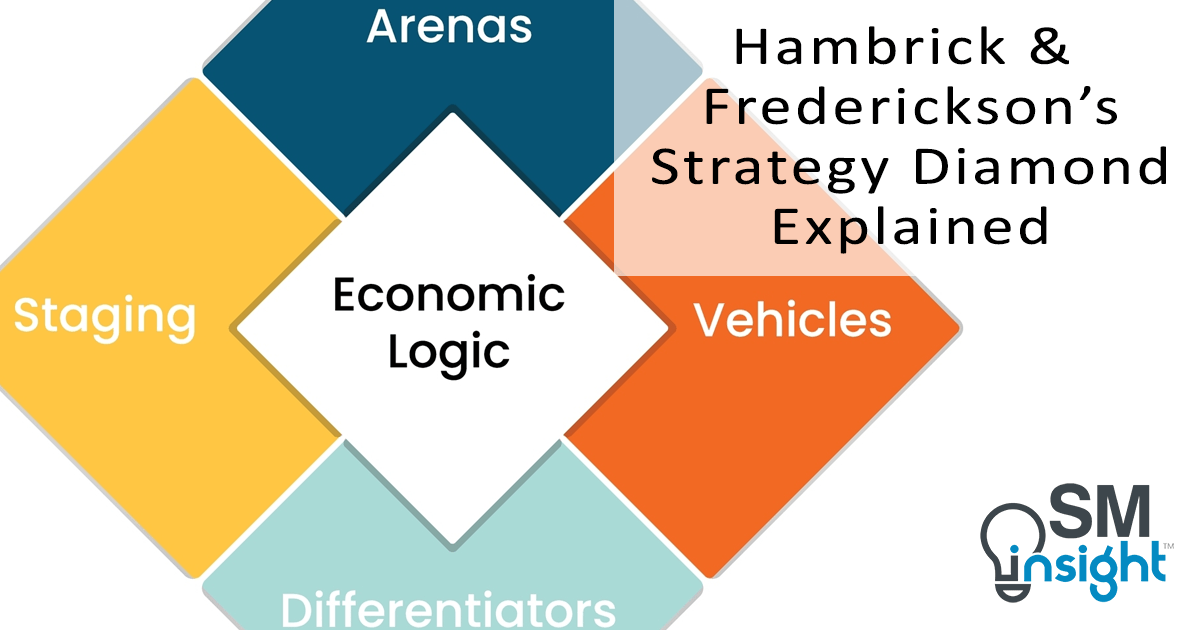

What is The Strategy Diamond

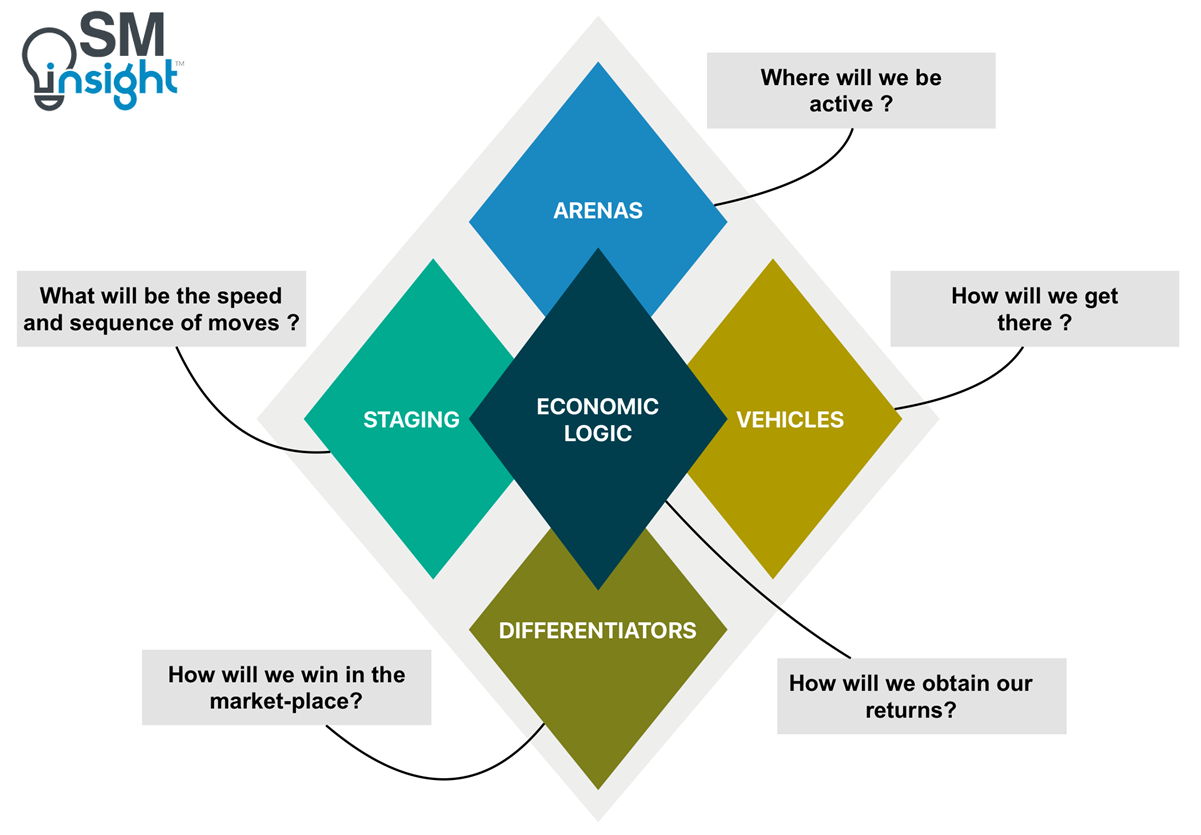

The strategy diamond defines the five elements of strategy: Arenas, Vehicles, Differentiators, Staging and Economic logic. Together these five facets form a strategy diamond framework, as depicted in the figure below.

Arena

A strategy starts by choosing an Arena that answers the “where” question or the business domain that a firm will operate in. It is important that the answer be as specific as possible.

An illustrative arena definition for the luxury car brand Rolls-Royce could be as follows:

“Rolls-Royce operates in the luxury automotive space, specializing in high-end vehicles that embody elegance and craftsmanship. We offer five models with a high level of bespoke customizations. We target affluent, price-insensitive individuals in top-tier cities across the world. Our core technologies include advanced engineering, cutting-edge features, meticulous design, manufacturing, and personalized experiences. We create value at every stage, from product development to post-purchase ownership.”

In contrast, a poorly defined arena example would be “We will be the best luxury brand in the world” which is a broad generalization that doesn’t mean much.

It is important to include product categories, market segments, geographic areas, and core technologies, as well as the value-adding stages the business intends to take on. The choice of arena needs to not only specify where the business will be active, but also how much emphasis will be placed on each if there are more than one option.

Vehicles

The means for attaining presence in a product category or a market segment should be a deliberate strategic choice as it matters greatly in the success of a strategy. Therefore, the selection of vehicles becomes crucial.

Vehicles communicate how a strategy will take the company to its goal.

Consider Microsoft’s venture into generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) as an example. Microsoft did not rank among the leading tech companies in AI. However, this changed with its acquisition of a stake in OpenAI, the company responsible for introducing ChatGPT to the world.

In Microsoft’s strategy, its vehicle to achieve dominance in AI could be defined as follows:

“By investing in cutting-edge AI research companies, Microsoft aims to harness their capabilities and integrate the technology into its own products such as Office tools, Bing search engine, and Edge browser. By incorporating AI technologies, Microsoft’s products will be enhanced to offer a robust set of tools that generate human-like text, facilitate meaningful conversations, enhance customer experiences, and drive business growth.”

Vehicles must specifically refer to how a company might pursue a new arena – whether through internal means or a new partner or some other outside source, or even through acquisition. This is where a strategist determines whether the organization is going to grow organically, or through acquisition, or a combination of both.

Vehicles should not be an afterthought or viewed as a mere implementation detail. Failure to explicitly consider and articulate the intended expansion vehicles can result in serious delays, unnecessary costs, or entirely stalling the initiative.

Differentiators

Having defined the arenas – where will we be active, and vehicles – how will we get there, defining the differentiator is the next step. Differentiators define why a customers will choose a company’s products/services over the competition.

In business, winning is the result of differentiators, but they don’t exist naturally. They require companies to make upfront, conscious choices about which weapons will be assembled, honed, and deployed to beat competitors in the fight for customers, revenues, and profits.

For example, Southwest Airlines attracts and retains customers by offering the lowest possible fares and extraordinary on-time reliability.

A company’s differentiator need not be at the extreme on one dimension; rather, having the best combination of several differentiators can also provide a tremendous market advantage.

Companies like Toyota have excelled in many segments and geographies within the automobile industry from affordable models like Corolla ($20,000) to luxury offerings like Lexus and Landcruiser ($100,000+). A combination of brand value, reputation of reliability and excellent customer service have acted as differentiators to its success.

Regardless of the intended differentiators, the critical issue for strategists is to make up-front, deliberate choices. Without that, there could be two unfortunate outcomes:

First, if the leadership does not define unique differentiation, none will occur. Differentiators don’t materialize naturally and are very hard to achieve. Companies will lose without them.

Second, without careful choices about differentiators, a company will be lost in pleasing a variety of customers with different preferences while simultaneously fighting competitors on a broad array of factors like price, better service, superior styling, etc. This leads to inconsistencies and extraordinary resource demands that seldom leads to success.

Differentiators must be mutually reinforcing (e.g., image and product styling), consistent with the firm’s resources and capabilities, and, most importantly, highly valued in the arenas the company has chosen.

Staging

While Arenas, Vehicles, and Differentiators form the substance of a strategy (what a company intends to do). Staging defines the speed and sequence of major moves.

Most strategies do not call for equal, balanced initiatives on all fronts at once. In execution, some initiatives must come first, some later.

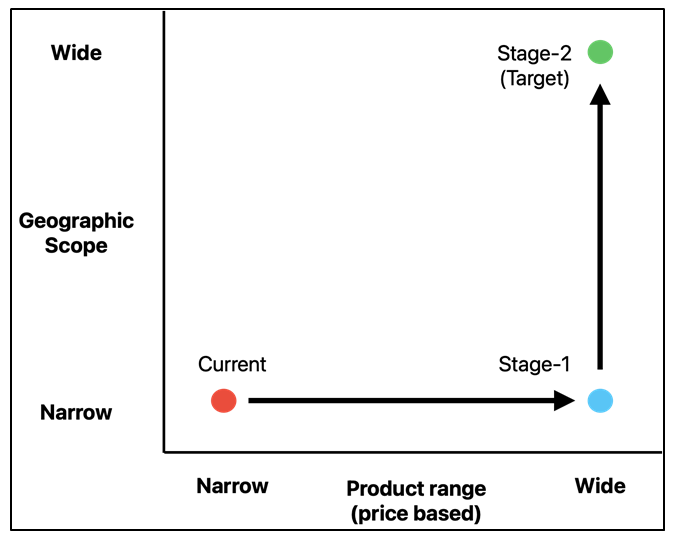

Consider a premium automobile manufacturer that has committed itself to broadening its product range and expanding into developing countries. To be able to achieve scale in developing countries, the company will also need low-cost models to drive volumes.

Since new product development needs significant time, resources and budget, the company may choose to focus on these initiatives in stage-1 before it focuses on marketing and expansion efforts.

Alternatively, it could also choose to enter the market with existing products first, gauge the demand and then develop new products that address the market need.

A staging chart plotted graphically for such a company will look as below:

Without defined staging, companies could waste a great deal of time and money.

Several factors influence staging. Resources, funding, and staffing are the common ones. Urgency is a second factor – some elements of a strategy may face brief windows of opportunity, requiring that they be pursued first and aggressively (examples – an immediate opportunity to acquire a company or form a joint venture).

A third factor is achieving credibility. Attaining certain thresholds in specific arenas, differentiators, or vehicles are sometimes mandatory to take the next step. The fourth factor could be targeting the low-hanging fruits first- a company might choose to tackle a part of the strategy that is relatively doable before attempting more challenging or unfamiliar initiatives.

The concept of staging remains largely unexplored in the strategy literature but forms an important component of a winning strategy.

Economic Logic

Economic logic is the final part of a strategy that defines how profits will be generated. Unless there is a compelling reason for profit, customers and competitors won’t let a firm become profitable.

In defining Economic logic, it is not enough to just have revenues that are above costs. Profits must also account for the cost of the capital invested in implementing the strategic initiative.

A successful strategy must have a central economic logic that serves as the fulcrum for profit creation. It could be the ability to charge a premium over a hard-to-match product or a loyal customer base or economy of scale that is hard for competitors to match.

For example, when Rolls-Royce unveiled its first electric car – Spectre EV for a price tag upward of $400,000, [2] the company’s economic logic for the launch rested on its strong brand value, an unmatched reputation, and a brand loyal customer base. As of 2023, It already has a waiting list stretching beyond two years for the model.[3]

A comprehensive strategy

While the five elements make up a strategy diamond, a good strategy is more than simply choices on the five fronts. It is an integrated, mutually reinforcing set of choices that form a coherent whole.

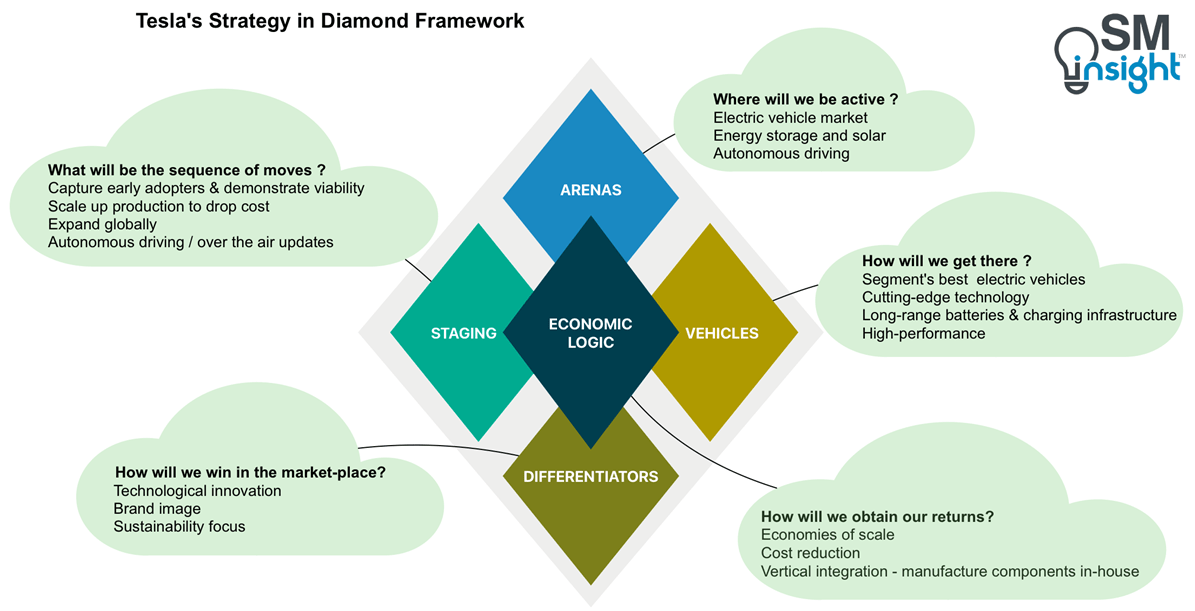

The example below illustrates how Tesla’s strategic approach, as observed through the diamond framework, has played a pivotal role in its success:

| Arenas | Tesla’s primary arena is the electric vehicle (EV) market. The company focuses on designing, manufacturing, and selling electric cars. Tesla’s arena also extends to energy storage solutions, solar panels, and the development of autonomous driving technology. In the big picture, its arena revolves around the renewable energy infrastructure. |

| Vehicles | Tesla’s “vehicles” include its range of electric cars, including sedans (Model S, Model 3), SUVs (Model X, Model Y), and the upcoming Cybertruck. These vehicles feature cutting-edge technology, high-performance capabilities, and long-range electric batteries, setting them apart from traditional combustion engine vehicles and other electric cars. |

| Differentiators | Tesla’s key differentiators lie in its technological innovation, brand image, and sustainability focus. The company has established itself as a pioneer in electric vehicle technology, with advanced battery systems, energy efficiency, and autonomous driving features. Tesla’s brand image is associated with luxury, innovation, and environmental consciousness, appealing to consumers seeking sustainable transportation options. |

| Staging | Tesla initially focused on producing high-end EVs to capture early adopters and demonstrate viability. As it gained acceptance and improved production capabilities, it expanded its offerings to include more affordable models, targeting a global consumer base. Tesla has also paced its development of autonomous driving technology, gradually introducing advanced features through over-the-air software updates. |

| Economic Logic | Tesla’s economic logic centers around achieving economies of scale, cost reduction, and creating a sustainable business model. The company plans to increase production volumes to drive down costs and make electric vehicles more accessible to the mass market. It also pursues vertical integration, manufacturing key components in-house to reduce cost and capture value along the supply chain. |

Putting strategy in its place

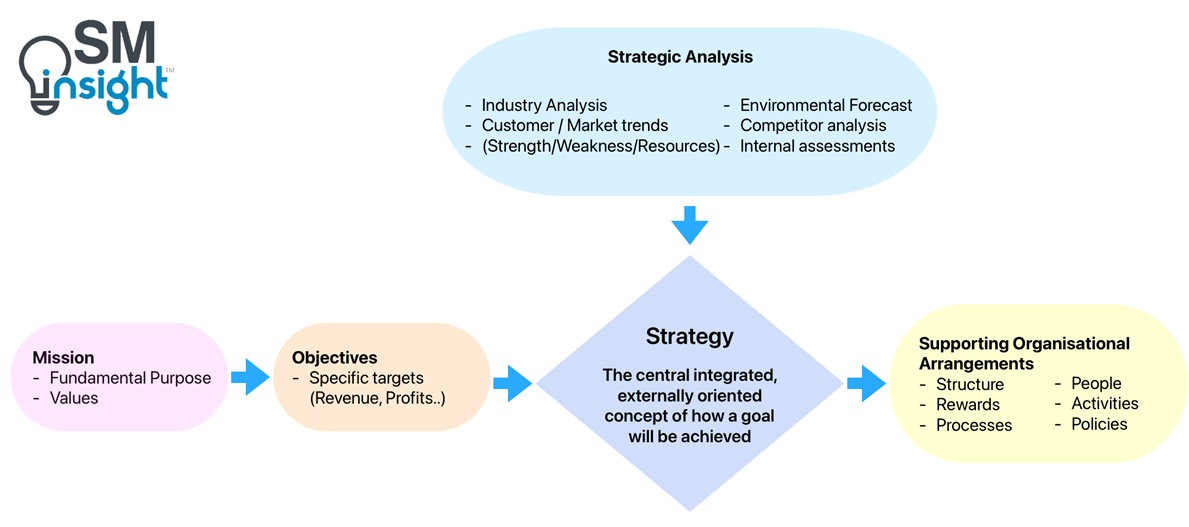

A strategy consists of an integrated set of choices, but it isn’t a catchall for every important choice a company makes. A company’s mission and objectives, for example, stand apart from and guide its strategy. Choices about internal organizational arrangements are not part of strategy either – compensation policies, information systems, or training programs aren’t a strategy.

These are critically important choices, which should reinforce and support strategy but they do not make up the strategy itself. The figure below shows how a strategy differs from other processes that an organization undertakes as a part of its business:

Testing the quality of a strategy

In an era of rapid, discontinuous environmental shifts, a strategy need not be static; it can evolve and be adjusted on an ongoing basis. Unexpected opportunities need not be ignored because they are outside the strategy. Some of the best strategies keep multiple options open and build in desirable flexibility through alliances, outsourcing, leased assets, investments in promising technologies, and numerous other means.

A strategy’s effectiveness can be evaluated using the following checklist:

- Does the strategy fit with what’s going on in the environment? Is there a healthy profit potential where in where the strategy headed? Does the strategy align with the key success factors of the chosen environment?

- Does the strategy exploit key resources? With the mix of resources, does this strategy give a good head start on competitors? Can the company pursue this strategy more economically than competitors?

- Will the envisioned differentiators be sustainable? Will competitors have difficulty matching them? If not, does the strategy explicitly include scope for innovation and opportunity creation?

- Are the elements of strategy internally consistent? Has the company made choices of arenas, vehicles, differentiators, and staging, and economic logic? Do they all fit and mutually reinforce each other?

- Does the company have enough resources to pursue this strategy? Does it have the funds, managerial time and talent, and other capabilities to perform all that is envisioned? Are the resources going to be spread too thin only to be left with a collection of feeble positions?

- Is the strategy implementable? Will the key constituencies allow pursuing this strategy? Can the company make it through the transition? Is the management team able and willing to lead the required changes?

Conclusion

The Hambrick & Frederickson’s Strategy Diamond provides a comprehensive framework for strategy formulation. It emphasizes the importance of understanding what a strategy truly entails, going beyond vague statements and fragmented elements. A strategy is a central, integrated concept that must serve as a guide to achieving objectives while orchestrating business activities. By employing the framework, companies can enhance their strategic decision-making processes and increase their chances of achieving long-term success.

Sources

1. “Are you sure you have a strategy?”. Researchgate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297471803_Are_you_sure_you_have_a_strategy/publication/297471803_Are_you_sure_you_have_a_strategy. Accessed 14 Jun 2023

2. “Rolls-Royce unveils its 1st fully electric car with $400K price tag: Spectre”. Fox29, https://www.fox29.com/news/rolls-royce-unveils-its-1st-fully-electric-car-with-400k-price-tag-spectre. Accessed 15 Jun 2023

3. “Rolls-Royce CEO: Order A Spectre Now, Take Delivery In 2025”. Insideevs.com, https://insideevs.com/news/668285/rolls-royce-spectre-2025-delivery-ceo-interview-exclusive/. Accessed 15 Jun 2023