Legendary Harvard professor Theodore Levitt argued that customers seek to “hire” a product to do a job. He said, “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!”

A marketer’s prime task is to understand the job the customer wants to be done and design products and brands that fill that need. Levitt also argued that there is no such thing as a commodity and that every product is differentiable.

Firms seek competitive distinction via product features—some visually or measurably identifiable, some cosmetically implied, and others claimed by reference to real or suggested hidden attributes that promise results or values different from those of competition.

Take coffee, for example. Though essentially a commodity, its price ranges from under $1 a cup to over $200 [1]. Similar differentiations are found everywhere, from airlines to fast food to automobiles. While the underlying product serves a basic need (extinguishing thirst, addressing transportation, or satisfying hunger), the products that achieve it vary widely in appeal and price.

To explain this variance, Levitt introduced the Whole Product Concept in his book Marketing Imagination [2] . This concept challenges the usual presumption that commodities are exceedingly price-sensitive and that a fractionally lower price gets more business. Instead, he argued that customers value a product in proportion to its perceived ability to help solve their problems or meet their needs.

What matters is the “total package of benefits” and not just the basic underlying product.

What is a product?

To the potential buyer, a product is a complex cluster of value satisfactions, a combination of tangible and intangible attributes that makes every touchpoint matter.

For example, to an automobile manufacturer, a car is a machine differentiated by design, size, color, options, horsepower, or miles per gallon.

To a customer, it may represent status, taste, rank, achievement, aspiration, or even what they care about—like sustainability in the case of EVs.

The notion of the product also includes how supporting services are built around it, for example, how the orders are fulfilled, the time from order to delivery, service quality, the quality of dealership staff interaction, etc.

Even when customers buy “generic” products like steel, wheat, subassemblies, investment banking, or aspirin, they buy something that transcends these designations and determines from whom they’ll buy, what they’ll pay, and whether they will be loyal.

Hence, in a market where the substantive content of competing vendors’ products is scarcely differentiable, power shifts to differentiating distinctions that influence buyers. The underlying basic product is the minimum required to give its producer a chance to play the game; it is never enough to win it.

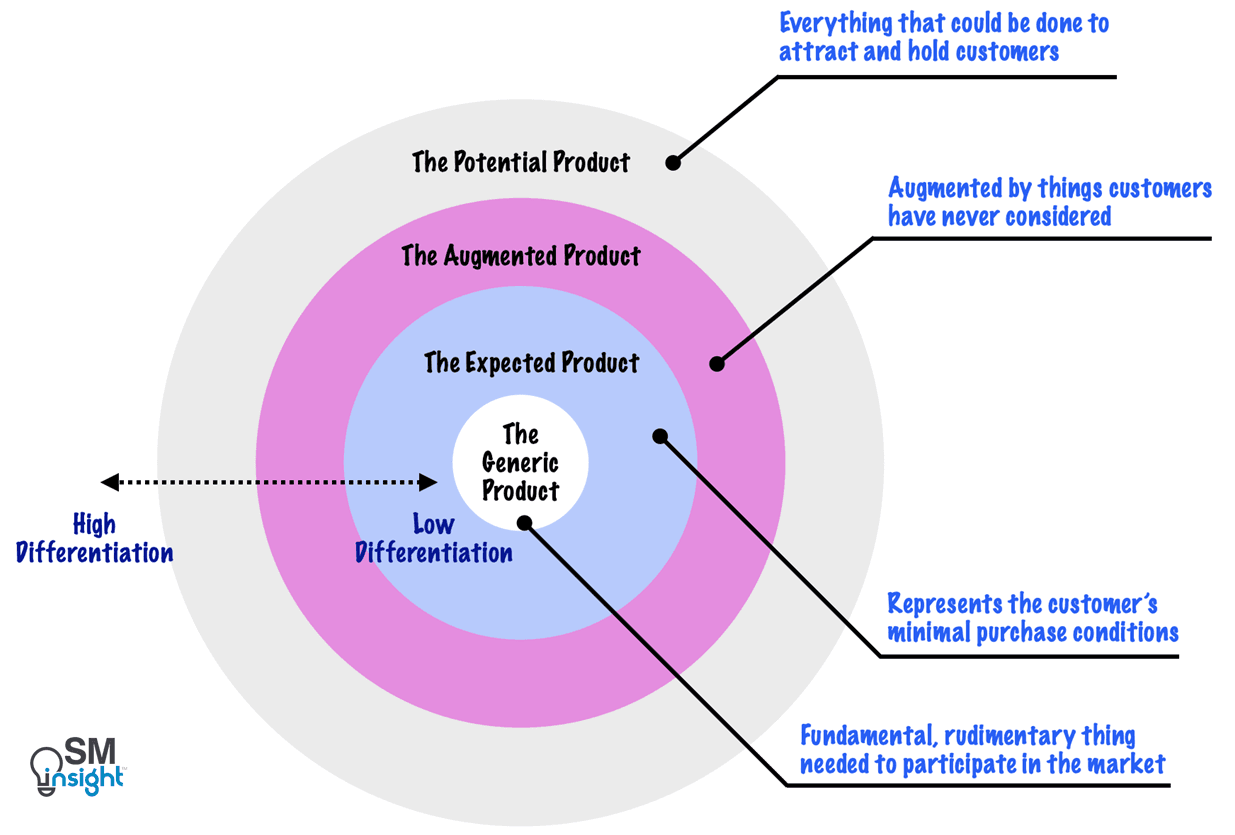

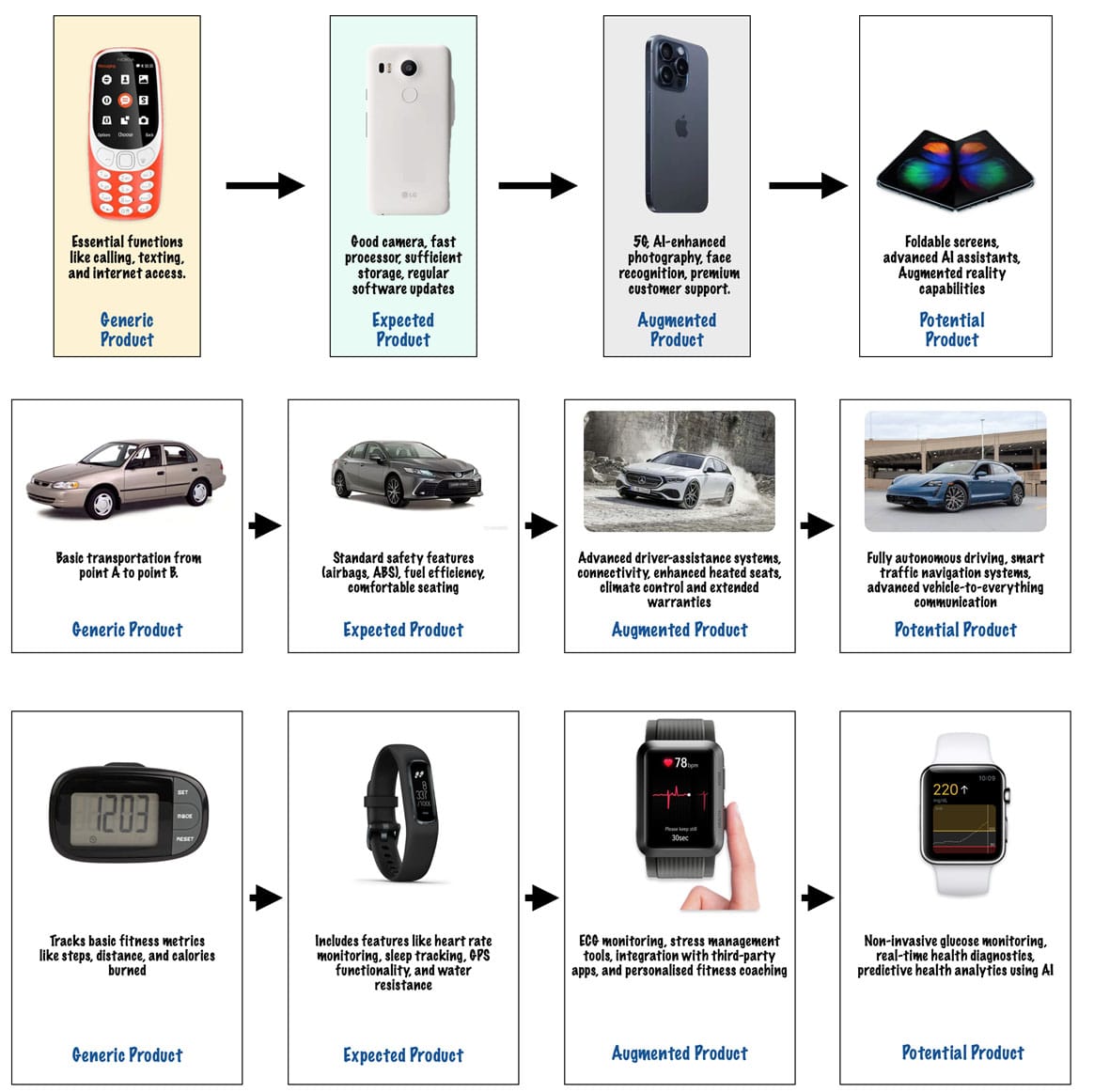

The Generic Product

The generic product is the fundamental, rudimentary, substantive thing needed to play the game of market participation. For the steel producer, it is the steel itself; for a bank, it’s loanable funds; for a realtor, it’s for-sale properties; for a retailer, it’s a certain mix of items; and for a lawyer, it’s passing the bar exam.

Even at this level, not all products are the same. One steel might be more “refined” and have “cleaner” chemistry; one bank may enjoy more trust than the other, and so on. In most cases, however, these differences are not significant enough to influence a purchase. What matters is the characteristics of the components that accompany the product.

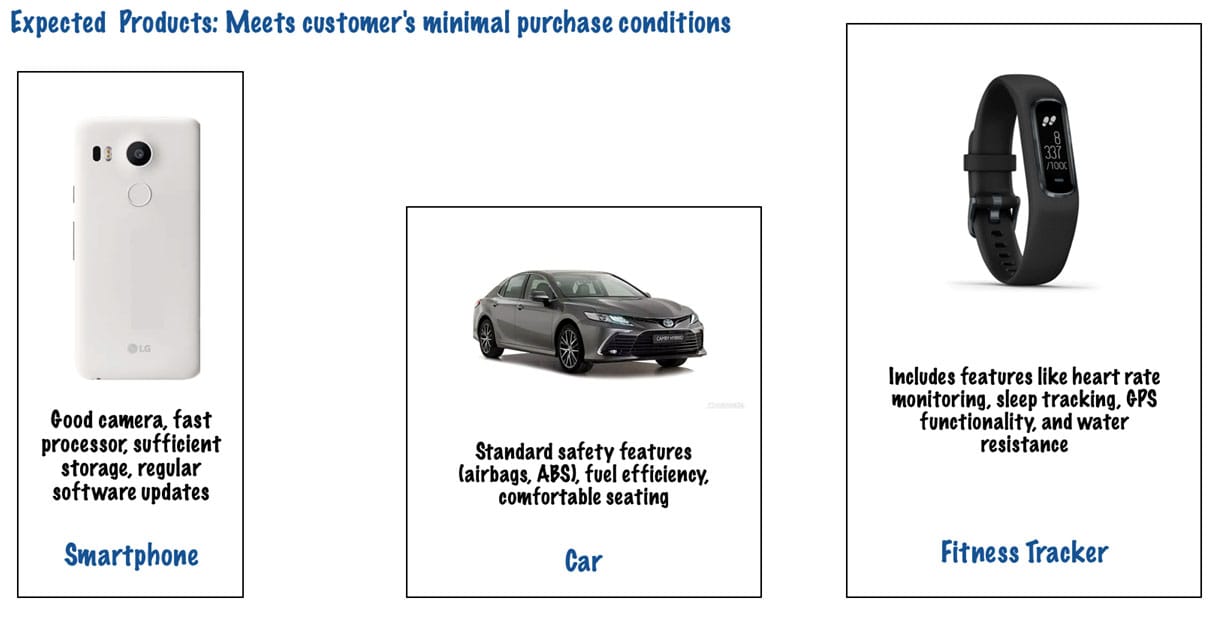

The Expected Product

The expected product represents the customer’s minimal purchase conditions. It is the generic product plus those features that the customer considers absolutely essential.

For an industrial buyer purchasing a raw material, the expected product could include:

- Delivery time: defined not only in terms of the date but also time to minimize inventory costs. The customer may also value flexibility in quantity or hassle-free responsiveness to delivery snags. It could also mean preferential treatment in case of shortages.

- Terms: include parameters like pricing that are valid for specific quantities for specific lengths of time. Customers may also value predefined agreements to account for volatility (a battery maker buying Nickel, for example, would value some price stability), discount structures related to early payments, add-on provisions for extended payment periods, etc.

- Support efforts: Depending on the product and its application, the purchaser may expect advice and support from the seller. For example, Aircraft manufacturers like Boeing and Airbus depend on turbine suppliers like Rolls Royce for supply, service, engineering support, and even design inputs for new product development.

- New ideas: Suppliers’ ideas and suggestions for efficient, cost-reducing use of the generic product may be expected by customers as a minimum in several industries.

These are some examples; in most cases, customers expect something more than the generic product. However, in every market, there exists a segment of customers who don’t want more.

For instance, in cloud computing services, some may seek a tailored infrastructure solution with custom security features and scalability options. In contrast, others might be content with a standard service plan offering basic storage and computing.

While it is hard for a seller to know what every customer values, the bottom line is that a generic product can be sold only if the customer’s wider expectations are met. Because sellers keep aligning their offerings to meet customer expectations, every new market eventually becomes differentiated.

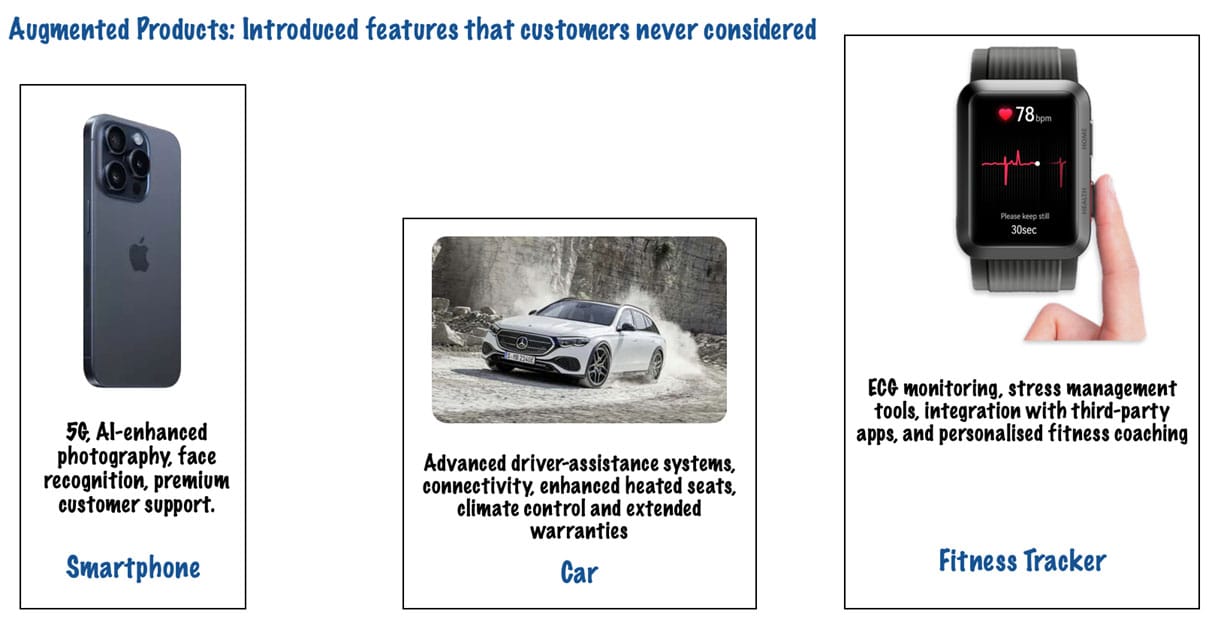

The Augmented Product

Differentiation need not be limited to giving customers what they expect. In most markets, customer expectations can be augmented by features that customers have never considered.

Tesla cars, for example, are equipped with air suspensions that automatically adjust the car’s suspension and ground clearance based on GPS coordinates and road conditions [4]. Nike’s self-lacing shoes adjust the fit based on the wearer’s foot shape and activity level in real time.

Customers obviously would not have asked for these features before the brands introduced them.

And such augmentations need not be limited to products. A manufacturer of health and beauty aids may offer warehouse management advice and training programs for the employees of its distributors. This is also an example of an augmented product—going beyond what the buyer requires or expects.

In each of these cases, the supplier exceeds the normal buyer expectations by studying the usage patterns of the generic product and making it so much better for the buyer by solving problems that the buyer never expected to be solved.

Introducing an augmented product, however, is not always beneficial and needs careful consideration. Not all customers for all products and under all circumstances may be attracted by an ever-expanding bundle of differentiating value satisfactions. Some may prefer lower prices to product augmentation, while others may not benefit from the extra.

As a rule, the more a seller expands the market by teaching and helping customers use their product, the more vulnerable that seller becomes to losing them. Customers who don’t need the extra benefits switch to other vendors based on parameters they value more, such as price.

Hence, an augmented product strategy must balance customer benefits and retention, making cost and price reduction equally important. This often presents a conflicting demand on the seller.

When the product matures, the market becomes more competitive, which drives the need for price and cost reductions to maintain profitability. This is also the stage to enhance the product with new features (product augmentation), which is crucial to differentiate it from competitors but leads to higher costs.

Augmented products are suited to mature markets or relatively experienced and sophisticated customers. When customers know (or think they know) everything and can do anything, the seller must test that assumption or be prepared to compete on price alone.

The best way to test a customer’s assumption that they no longer need or want all or any part of the augmented product is to consider what else could be offered to the customer. This leads to the next class of product – the potential product.

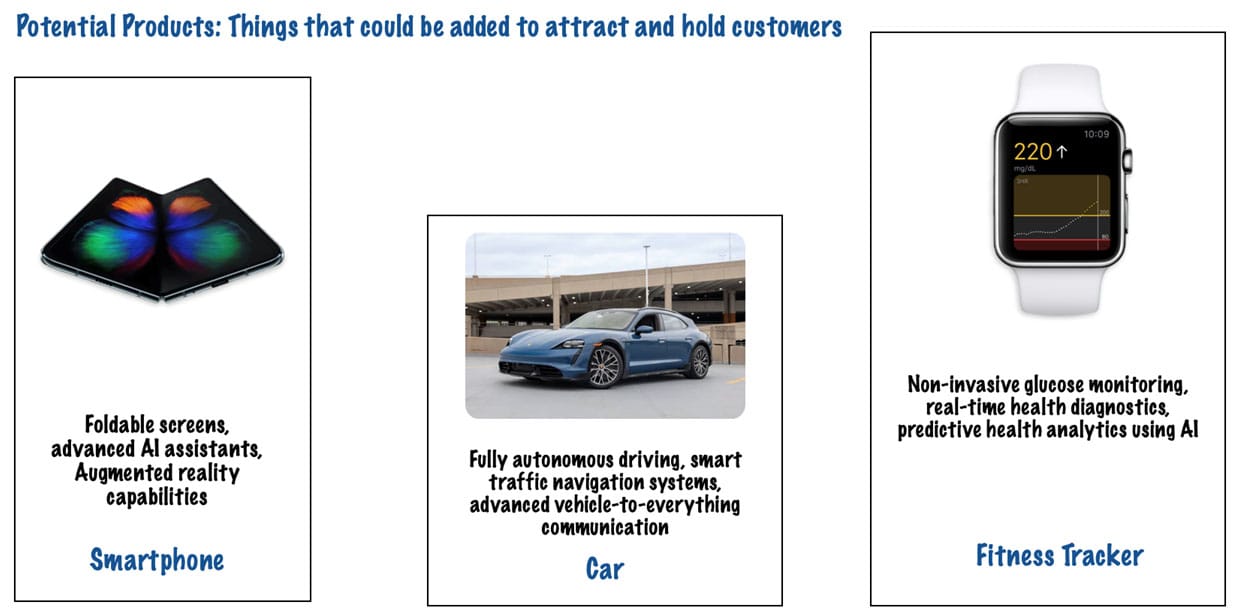

The Potential Product

The potential product includes everything that could be done to attract and hold customers, including technical changes, offering alternatives based on market research, using new production methods for better quality and components, varying product characteristics, and more.

Such offerings vary depending on economic and competitive conditions. Competition may be a function of not simply what other suppliers offer but also what suppliers of substitute products offer.

Several parameters, including economic conditions, business strategies, customers’ wishes, and competitive conditions, can determine what sensibly defines a potential product. Only the budget and the imagination limit the possibilities.

There is no such thing as a commodity

As with most things in business, products are never simple, static, or can be explained reliably using textbook taxonomies.

There exists no real boundary between the four classes of products. What’s “augmented” for one customer may be “expected” by another; what’s “augmented” under one circumstance may be “potential” in another. What’s “generic” in periods of short supply may be “expected” in periods of oversupply.

One thing is certain: there is no such thing as a commodity, at least from a competitive point of view. Everything is differentiable and (in most cases) differentiated.

Whole product marketing

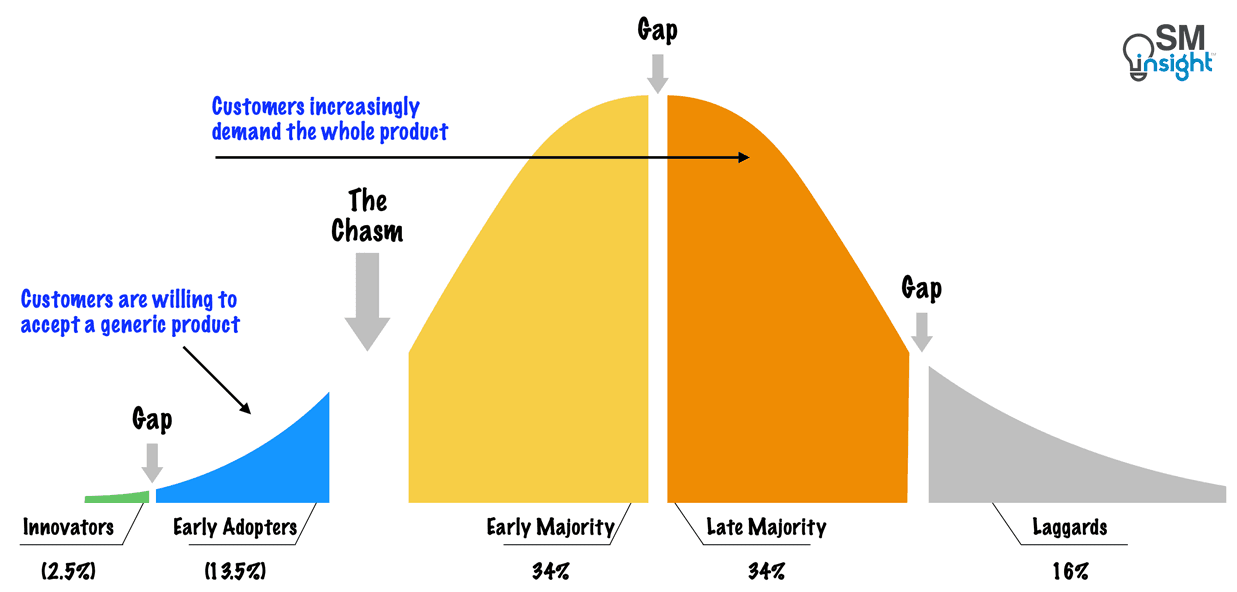

In his book Crossing the Chasm [5], Geoffrey Moore explains how the whole product concept influences marketing strategies. He contends that many high-tech executives believe marketing is solely about long-range strategic thinking followed by tactical sales support, with nothing significant in between. However, Moore argues that marketing’s most powerful contribution occurs right in between, which he terms whole product marketing.

When a disruptive innovation is introduced, the marketing battle initially takes place at the level of the generic product—the things in the center. At this stage, the product is the hero in the battle for the early market. As marketplaces develop and enter the mainstream market, products in the center become increasingly alike, and the battle shifts to the outer circles.

To dominate a mainstream marketplace, marketers must understand what a whole product consists of and how to organize a marketplace to provide a whole product that incorporates the company’s offering.

The single most important difference between early markets and mainstream markets is that customers in the former are willing to take responsibility for piecing together the whole product, whereas the latter are not. In diffusion of innovation theory, this customer gap is known as a “chasm,” which explains why products fail when organizations don’t plan on offering whole products that appeal to mainstream markets.

Whole product management

How a company manages its marketing can become the most powerful form of differentiation. Indeed, that may be how some companies in the same industry differ most from one another.

Putting somebody in charge of a product that’s used the same way by a large segment of the market vs. putting somebody in charge of a market for a product that’s used differently in different market segments clearly changes how focus, attention, responsibility, and effort are channeled. Companies that organize their marketing for the latter generally have a clear competitive advantage.

For example, coffee, soap, flour, beer, salt, oatmeal, pickles, etc., were once commodities. Today, a differentiated version of each of these products exists. Such differentiations are also seen in services such as banking, insurance, credit cards, stock brokerage, restaurants, opticians, and more.

In each of these cases, especially consumer tangibles, the general presumption is that the competitive distinction is due to packaging and advertising. Even substantive differences in the generic products are thought to be less significant compared to ads and packaging.

This, however, is a wrong presumption. The amount of careful analysis, control, and fieldwork that characterizes marketing management is masked by the visibility of their advertising or presumed generic product uniqueness.

For example, while branded food products companies advertise heavily, they work equally hard with wholesale and retail distributors. Though big brands try to create consumer “pull” through advertising and promotion, they also try to create retailer and wholesaler “push.”

Differentiation is most readily apparent in branded, packaged consumer goods, in the design, operating character, or composition of industrial goods, or in the features or “service” intensity of intangible products. However, differentiation also depends powerfully on how one operates the business. The way the marketing process is managed can allow many companies, especially those that offer generically undifferentiated products and services, to escape the commodity trap.

Sources

1. “Britain’s most expensive cup of coffee is £265”. The Telegraph, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2024/04/17/britains-most-expensive-cup-of-coffee-is-265/ Accessed 23 Mar 2025.

2. “Marketing Imagination”. Theodore Levitt, https://www.amazon.com/Marketing-Imagination-Expanded-Theodore-Levitt/dp/0029190908 Accessed 23 Mar 2025.

3. “Marketing Success Through Differentiation—of Anything”. Theodore Levitt (HBR), https://hbr.org/1980/01/marketing-success-through-differentiation-of-anything Accessed 02 Mar 2025.

4. “Tesla Smart Air Suspension Explained”. Find My Electric, https://www.findmyelectric.com/blog/tesla-smart-air-suspension-explained/ Accessed 24 Mar 2025.

5. “Crossing the Chasm – Marketing and Selling Disruptive Products to Mainstream Customers”. Geoffrey A. Moore, https://www.amazon.in/dp/0062292986 Accessed 03 Mar 2025.