Services constitute over 60% of the world’s GDP [1], yet managing service quality is harder than managing the quality of goods. While goods can be evaluated through tangible cues such as style, hardness, color, label, feel, package, and fit, few cues exist for services.

We’re all familiar with the frustrations of service failures. Your laptop returns from repair with the same issue it was sent in for. After spending hours with tech support, your internet connection fails again within days. A customer service agent promises to escalate your issue, yet you never hear back.

Examples of poor service are widespread; in survey after survey, services top the list in consumer dissatisfaction [2]. Companies today have more data about their customers, but the analytics employed to turn data into information are mostly not good enough.

While customers are convinced that someone is treating them badly, managers think defiant employees are the source of the malfunction. Even though services can fail because of human incompetence, a lack of systematic methods for design and control is often the core of the problem.

Matching service specifications to customer expectations requires the ability to describe critical service process characteristics objectively and to depict them so that employees, customers, and managers know what the service is, can see their roles, and can understand all the steps and flows involved in the service process.

A service blueprint is a picture or map that portrays the customer experience and the service system so that the people involved can understand the service objectively, regardless of their roles or individual points of view.

It simultaneously depicts the service process, the points of customer contact, and the evidence of service from the customer’s point of view:

A service blueprint serves as an operational tool that shows the orchestration of people, touchpoints, processes, and technology both frontstage (what customers see) and backstage (what is behind the scenes). It helps visualize the components of a service to analyze, implement, and maintain it.

Evolution of Service Blueprinting

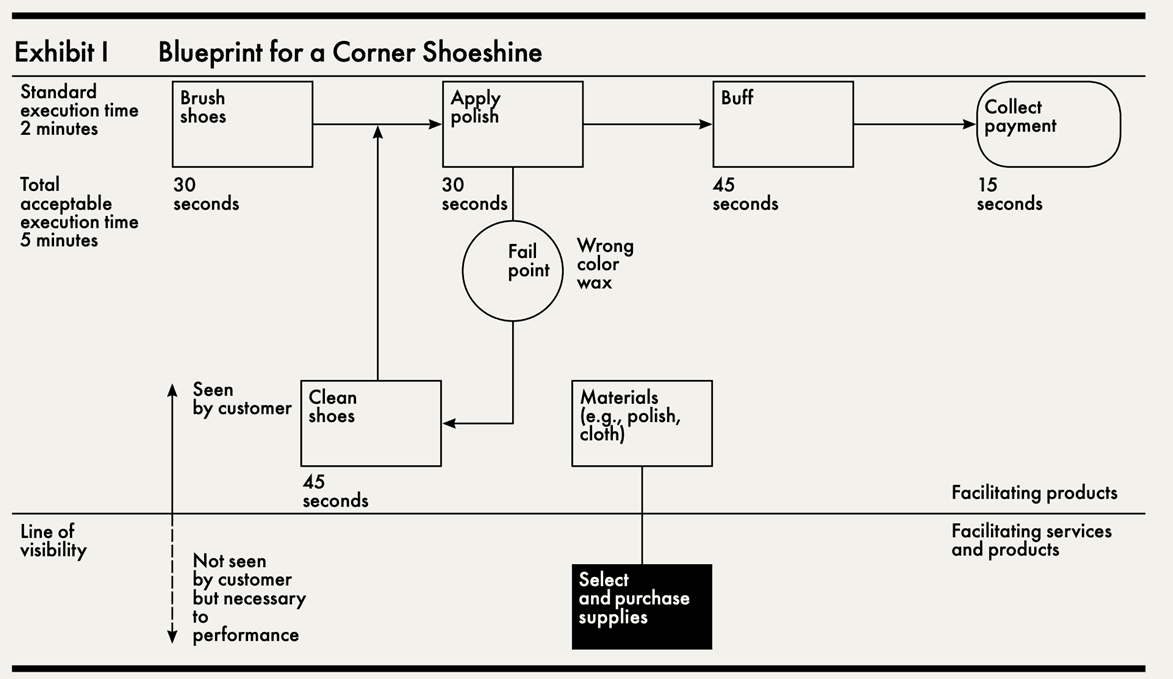

Service blueprints were first described by G. Lynn Shostack, a bank executive, in a Harvard Business Review article titled “Designing Services That Deliver” in 1984 [4]. Her approach helped codify service delivery, which at the time was viewed as intangible or ephemeral to something that could be documented, measured, controlled, and improved upon.

Over the years, service blueprints have dramatically evolved, both visually and structurally, to capture the customer experience while providing enough operational detail to document how a service is delivered. They help understand the operational complexity of services without becoming mired in the details of other business process modeling methods.

Key Components Of A Service Blueprint

One of the most significant differences between service blueprints and other process flow diagrams is the primary focus on customers and their experience. This is why the concept of frontstage and backstage is at the core of a service blueprint design.

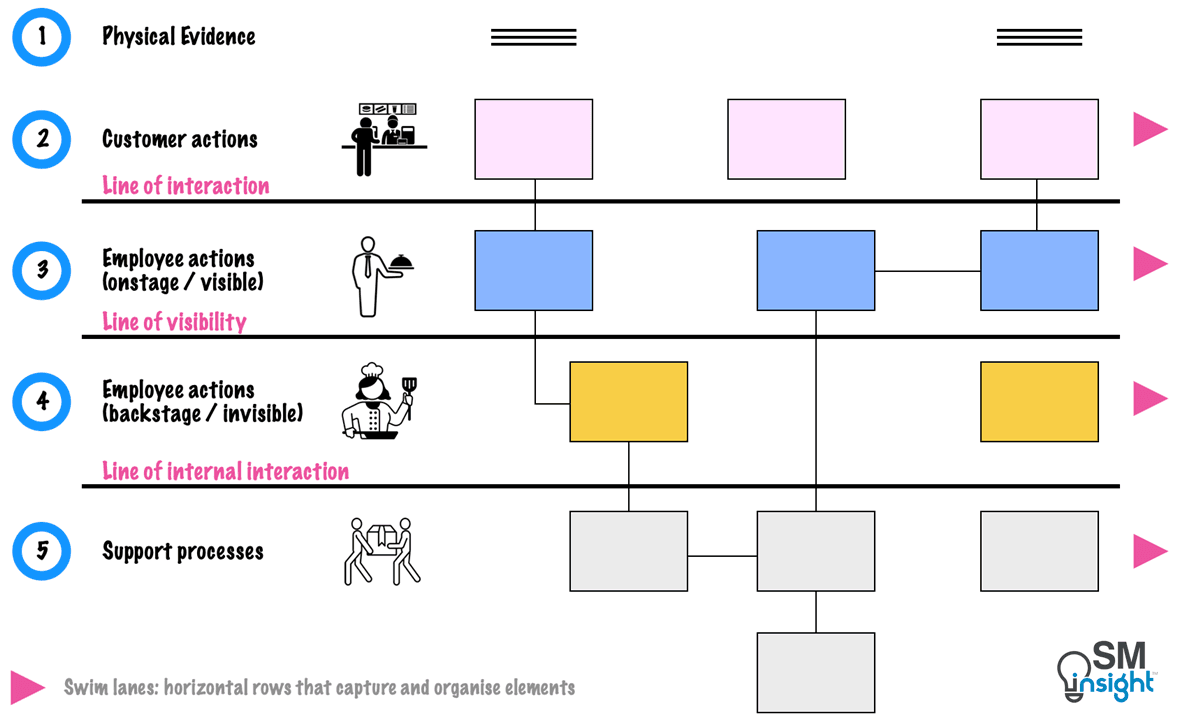

The key components of service blueprints include customer actions, onstage/visible employee actions, backstage/invisible employee actions, and support processes. In addition, physical evidence of the service (as applicable) is indicated at the very top of the blueprint:

Conventions for drawing service blueprints are not rigidly defined. Hence, the particular symbols used, the number of horizontal lines in the blueprint, and the labels for each part of the blueprint may vary depending on the complexity of the processes.

These variations are unimportant as long as the blueprint’s purpose is clear and it is viewed as a useful technique rather than a set of rigid rules. In fact, its flexibility, when compared with other process mapping approaches, is one of its major strengths.

- Customer actions: this area encompasses the steps, choices, activities, and interactions the customer performs while purchasing, experiencing, and evaluating the service. The total customer experience is apparent in this area of the blueprint.

For instance, in legal services, the customer’s actions might include deciding to contact an attorney, making phone calls to the attorney, attending face-to-face meetings, sharing documents, and so on. - Onstage/visible contact employee actions: these are activities performed by the contact employee that are visible to the customer. In a restaurant, this could include taking reservations, receiving customers, explaining the menu, taking orders, serving food, and so on.

- Backstage/invisible contact employee actions: these are contact employee actions that occur behind the scenes to support the onstage activities. For example, a waiter may prepare cutlery in advance, coordinate with the kitchen staff on meal orders, restock supplies, or enter orders into the restaurant’s management system.

- Support processes: this section of the blueprint covers the internal services, steps, and interactions required to support the contact employees in delivering the service.

In the restaurant example, support services could include kitchen inventory management, staff scheduling, training, IT systems support, health and safety compliance, and so on. - Physical evidence: Typically, above each point of contact, the actual physical evidence of the service is listed. For a food serving process in a restaurant, physical evidence could include the contact’s attire, cutlery, menu, table settings, food presentation, and more.

Three horizontal lines separate the four key action areas:

- Line of interaction: everything above this line represents direct interactions between the customer and the organization. Every time a vertical line crosses this horizontal line of interaction, a direct contact between the customer and the organization, or a service encounter, has occurred.

- Line of visibility: this critically important line separates all service activities visible to the customer from those that aren’t. When reading blueprints, this line helps analyze the extent to which visible evidence of the service is provided to customers.

This line also separates what the contact employees do onstage from what they do backstage. For example, a doctor may perform the actual exam and answer the patient’s questions above the line of visibility but read the patient’s records in advance or dictate notes following the exam below the line of visibility. - Line of internal interaction: separates customer-contact employee activities from those of service support activities and people. Vertical lines cutting across the line of internal interaction represent internal service encounters.

In designing effective service blueprints, diagramming must start with the customer’s experience and then work into the delivery system. The boxes shown within each action area depict steps performed or experienced by the actors at that level.

Examples of Service Blueprints

Overnight hotel stay

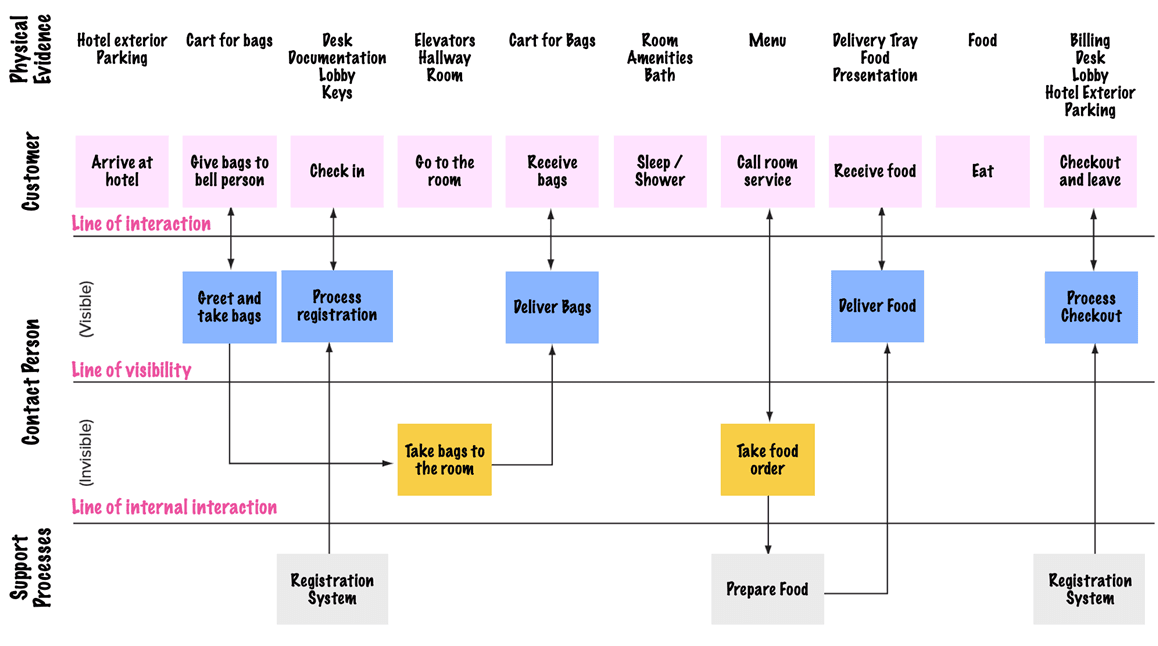

Shown below is a simplified service blueprint for an overnight hotel stay. The guest first checks in and then goes to the hotel room, where various steps occur (receiving bags, sleeping, showering, eating breakfast, and so on), and finally checks out.

(Image adapted from Services Marketing, Aligning Service Design and Standards FIGURE 8.6 [3])

The blueprint easily identifies employees directly interacting with the customer. Each step in the customer action area is also associated with various forms of physical evidence—from the guest registration form to the lobby and room decor to the uniforms worn by frontline employees.

Technology-Delivered Self-Service

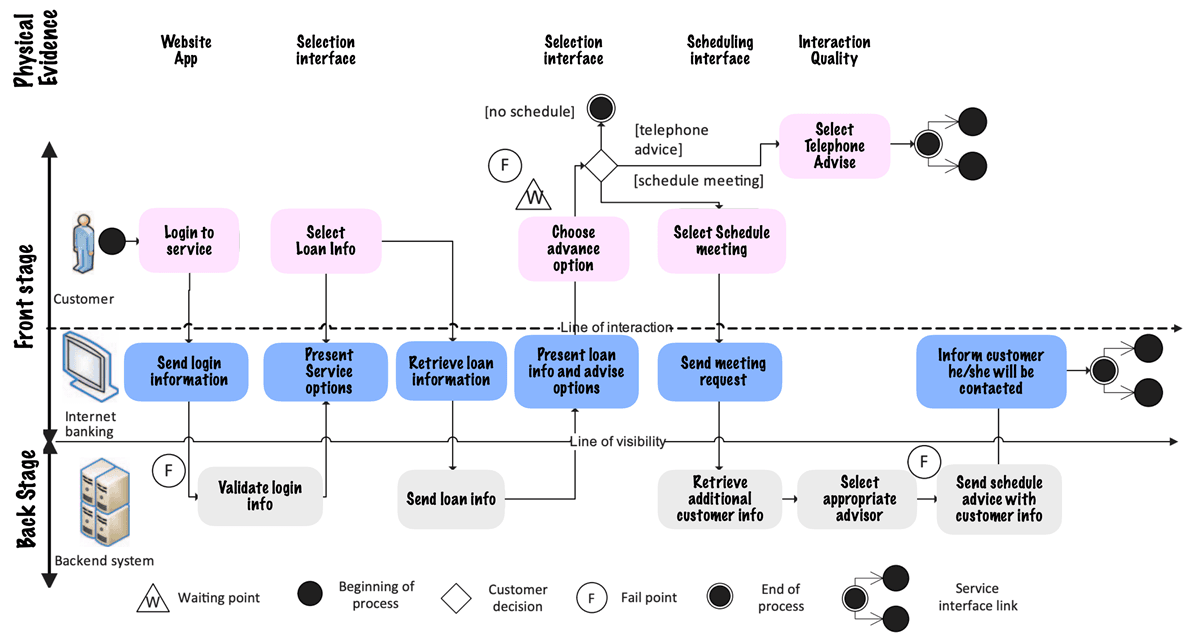

Service blueprinting can also be effectively used to design services where no employees are involved (except when there is a problem or the service does not function as planned). In such cases, the contact person areas of the blueprint are not needed.

Instead, the area above the line of visibility can illustrate the interface between the customer and the website (or any other means, such as a kiosk). This area can be relabeled as onstage/visible technology. The backstage contact person actions area is irrelevant in this case.

Sometimes, services involve a combination of human interaction and technology. For example, during an airline’s boarding process, check-in might be completed via an electronic kiosk, while baggage handling, security screening, and ticket processing are managed by staff.

In such processes, the blueprint would include all three contact rows: one for technology, one for the onstage contact person (visible), and one for the backstage contact person (invisible). The customer typically interacts with a “backstage contact person” only when encountering a problem. Otherwise, these persons remain “invisible”.

Building a Service Blueprint

Building a blueprint requires a structured and collaborative approach. This includes getting the right tools and people in place, providing clear instructions, and facilitating people through the activity from start to finish.

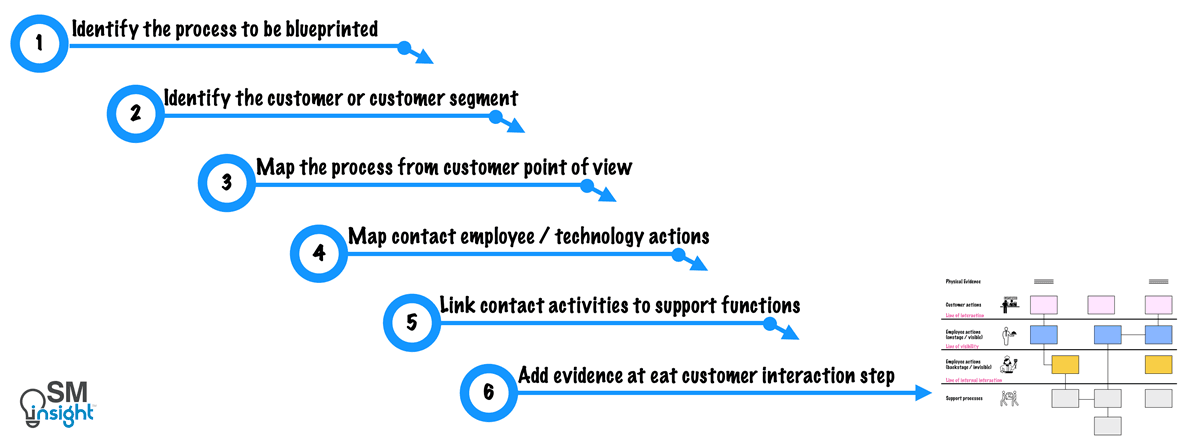

Because many of the blueprint’s benefits evolve from the process of doing it, it is important to involve cross-functional representatives and use accurate customer information. Here is a six-step structured process for building blueprints:

Step 1: Identify the Service Process to Be Blueprinted

Because blueprints can be developed at various levels, the first step is to agree on a starting point. To do this, identify the people whose expertise would be needed to populate the blueprint and get them together in the same room. While it is preferable to have this meeting in person, this can also be done virtually.

For example, the overnight hotel stay service blueprint shown earlier is at the basic service concept level. Variations based on specific services are not shown. More subprocesses could be included, and if certain elements of the process were found to be problem areas or bottlenecks, a detailed blueprint of the subprocesses could be further developed.

Step 2: Identify the Customer or Customer Segment Experiencing the Service

Each customer segment’s needs are different, requiring variations in service or product features. Blueprints are most useful when developed for a particular customer or customer segment, assuming the service process varies across segments.

For overnight hotel stays, for example, the blueprint may be separated based on the type of guests, such as business travelers, families, group travelers, solo travelers, luxury travelers, and so on.

It may be possible to combine customer segments into one blueprint at a very abstract or conceptual level. However, once sufficient detail is reached, separate blueprints should be developed to avoid confusion and maximize their usefulness.

Step 3: Map the Service Process from the Customer’s Point of View

Customers and their actions make up the top row of a service blueprint. Developing it involves charting the choices and actions that the customer performs or experiences in purchasing, consuming, and evaluating the service.

This helps maintain focus on what customers are asked to do and how their experiences unfold over time. It creates a customer-centered lens for understanding the intended experience and how it is delivered.

Identifying the service from the customer’s point of view before anything else helps avoid focusing on processes and steps that have no customer impact. It also forces agreement on who the customer is (which can be difficult at times [6]).

For example, airline passengers might see the service as beginning with the booking process and ending only after they’ve reached their final destination and collected their luggage. In contrast, the airline might view their service as starting at check-in and concluding when the passenger disembarks from the plane.

Because developing a blueprint requires extensive research and observation, the process helps uncover aspects of the service that are crucial to customers but may have been overlooked by the provider.

Step 4: Map Contact Employee Actions and/or Technology Actions

In this step, the lines of interaction and visibility are drawn first. Then, the process from the customer contact person’s point of view is mapped, distinguishing visible onstage activities from invisible backstage activities.

For existing services, this step involves questioning or observing frontline operation employees to learn what they do and which activities are performed in full view of the customer versus which activities are carried out behind the scenes.

For technology-delivered services or those that combine technology and human delivery, the required actions of the technology interface are also mapped above the line of visibility. If no employees are involved in the service, the area can be relabeled as “onstage technology actions.”

If both human and technology interactions are involved, an additional horizontal line can separate “visible contact employee actions” from “visible technology actions.” Using the additional line facilitates reading and interpretation of the service blueprint.

Step 5: Link Contact Activities to Needed Support Functions

The line of internal interaction can then be drawn, and linkages from contact activities to internal support functions can be identified. In this process, the direct and indirect impact of internal actions on customers becomes apparent.

Internal service processes become more important when viewed in relation to their link to the customer. Alternatively, certain steps in the process may be considered unnecessary if there is no clear link to the customer’s experience or an essential internal support service.

Step 6: Add Evidence of Service at Each Customer Action Step

The last step is to add the evidence of service to illustrate what the customer sees and experiences as tangible evidence of the service at each step in the process.

A photographic blueprint, including photos, slides, or video of the process, can be very useful at this stage to analyze the impact of tangible evidence and its consistency with the overall strategy and service positioning.

Benefits of Using Service Blueprints

The growth of digital channels and new communication technologies has enabled businesses to adopt an omnichannel approach to customer service. Firms today must manage interactions across multiple channels such as call centers, webchats, SMS, messaging, email, and social media.

For example, a customer support conversation might begin on Twitter, continue with text messages, and end with a phone call. Customers don’t expect to stop and explain their problems at each channel interaction.

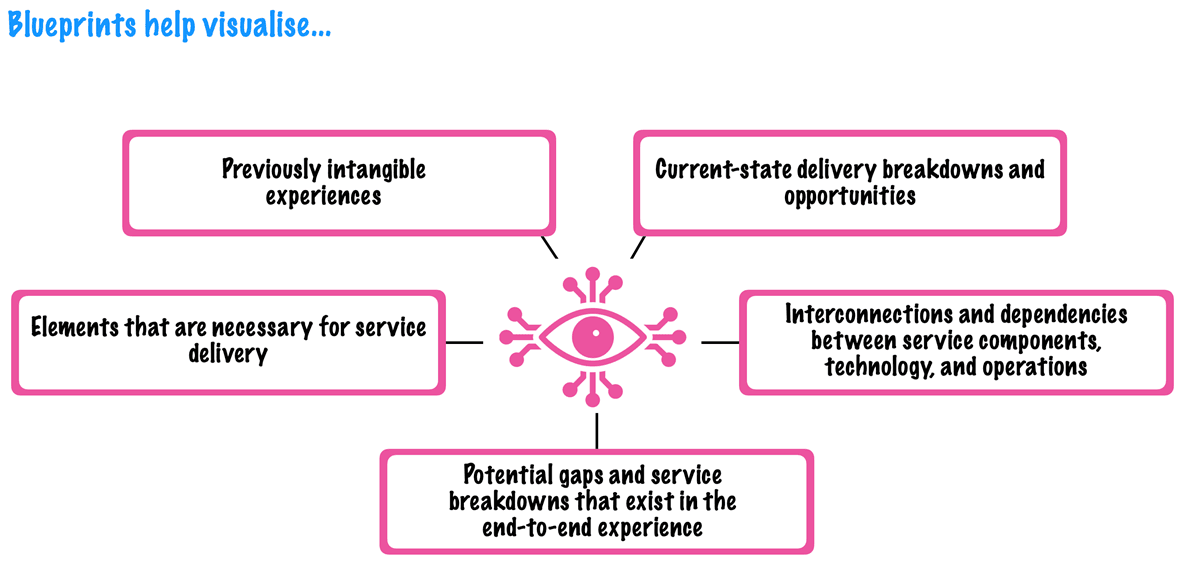

Blueprints help solve the complexity of today’s service experiences and ecosystems. They help visualize, align, and prototype the components of a service. While valuable for many reasons, some of the key benefits of blueprints include:

Visualization

Service blueprints help understand all the moving parts of a service—their interconnections, dependencies, and breakdowns. Visually communicating this knowledge to collaborators and stakeholders makes what was before an abstract concept tangible and easier to address directly.

One of the key benefits of a service blueprint is that it visualizes service experiences across silos.

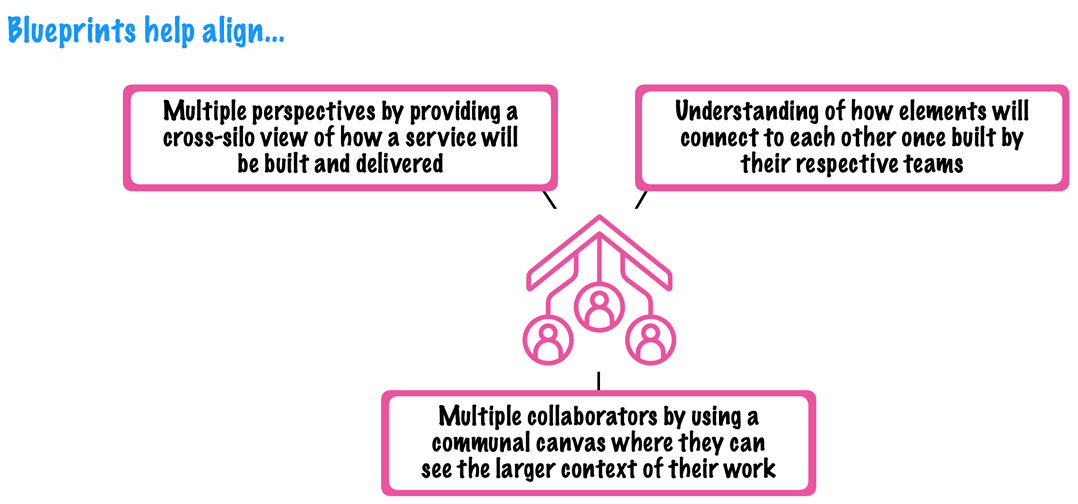

Alignment

Blueprints provide a common canvas upon which multiple roles within an organization can see themselves and the parts of the experience for which they are responsible. This brings alignment across end-to-end service processes and helps organizations unite around a common understanding of how services function.

This is particularly valuable when multiple teams, groups, and/or divisions need to collaborate to deliver a service vision. Blueprints help ensure that, once built, the pieces of an experience will fit together correctly as intended.

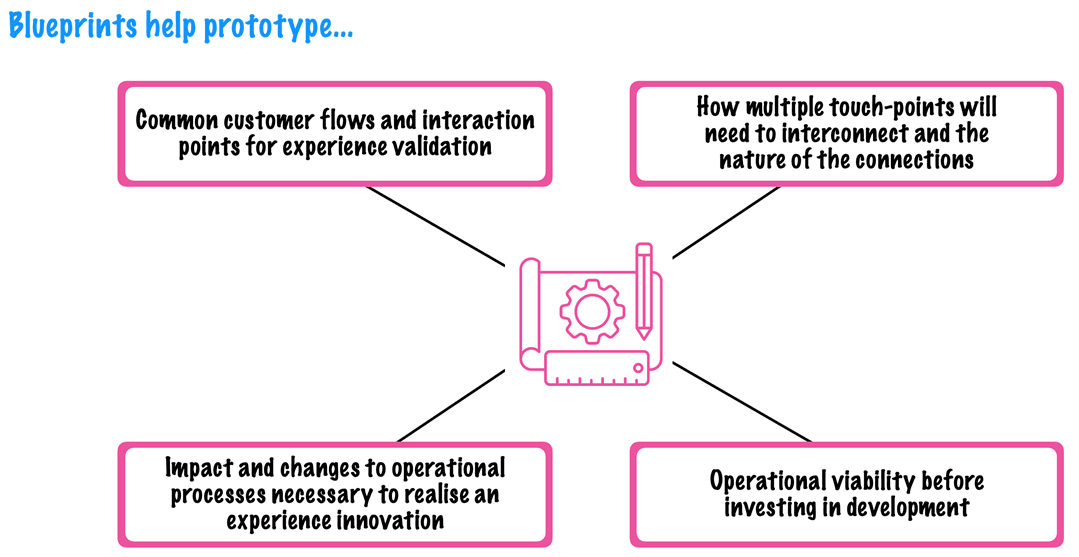

Prototyping

The process of developing a service blueprint is also a great way to quickly prototype service delivery approaches at a low level of fidelity.

At any stage of the design process, blueprints can be used as canvases to capture insights and explore business and operational viability for different solutions. They can also be used as scripts to facilitate and visualize customer flow and the architecture of the service experience.

Reading and Using Service Blueprints

Service blueprints can be read in various ways, depending on the purpose.

To Understand the Customer’s View

If the purpose is to understand the customer’s view of the process or the customer experience, the blueprint can be read from left to right, tracking the events in the customer action area.

Questions that might be asked in this case include:

- How is the service initiated by the customer?

- What choices does the customer make?

- Is the customer highly involved in co-creating the service, or are few actions required of the customer?

- What is the physical evidence of the service from the customer’s point of view?

- Is the evidence consistent with the organization’s strategy and positioning?

To Understand Contact Employees’ Roles

If the purpose is to understand contact employees’ roles or the integration of onstage technology with contact employee activities, the blueprint can also be read horizontally, but this time, it should focus on the activities directly above and below the line of visibility.

Questions that might be asked here include these:

- How rational, efficient, and effective is the process?

- Who interacts with customers, when, and how often?

- Is one person responsible for the customer, or is the customer passed off from one contact employee to another?

- Are interactions and handoffs between people and technology integrated and seamless from the customer’s point of view?

To Understand the Integration of the Various Elements

If the purpose is to understand the integration of the various elements of the service process or to identify where particular employees fit into the bigger picture, the blueprint can be analyzed vertically.

This clarifies what tasks and which employees are essential in delivering customer service. The blueprint also shows the linkages from internal actions deep within the organization to frontline effects on the customer.

Questions that might be asked include:

- What backstage actions support critical customer interaction points?

- What are the associated support actions?

- How do handoffs from one employee to another take place?

To Redesign a Service

If the purpose is service redesign, the blueprint can be looked at as a whole to assess the complexity of the process, how it might be changed, and how changes from the customer’s point of view would affect the contact employee and other internal processes, and vice versa.

Blueprints can also be used to assess the service system’s overall efficiency and productivity and evaluate how potential changes will affect it [7]. They can be analyzed to determine likely failure points or bottlenecks in the process and customer pain points.

When such points are discovered, a firm can introduce measures to track failures, or that part of the blueprint can be exploded so that the firm can focus in much greater detail on that piece of the system.

Journey Maps vs. Service Blueprints

A Customer Journey Map (CJM) helps visually illustrate an individual customer’s needs, the series of interactions that are necessary to fulfill those needs, and the resulting emotional states a customer experiences throughout the process [8]. CJMs are powerful storytelling tools that help build empathy and let organizations identify areas of the experience that could be improved or learned more about.

In contrast, a service blueprint is not about documenting the customer experience. It uses the customer experience as a starting point and unpacks it to expose how the organization supports that journey [9].

While CJMs help document surface customer experiences, service blueprinting helps “evidence” an organization’s reality. The fundamental value a blueprint provides is an objective picture based on the reality of how the organization delivers, what it delivers, and the end-to-end view of how it is orchestrated.

| Service Blueprinting | Customer Journey Maps | |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Primarily used by internal teams to document and analyze the organization’s processes that support customer interactions. | Focuses on understanding the customer’s experience from their perspective. |

| What it does | Illustrates how different departments and roles contribute to the customer experience, highlighting both visible (front-stage) and invisible (back-stage) actions that affect service delivery | Captures emotions, thoughts, and actions of customers at various touchpoints throughout their journey. Identifies pain points and opportunities for enhancing the customer experience (front-stage) |

| Scope | Encompasses the entire service delivery process, including customer actions, front-stage interactions, back-stage actions, and support processes. This comprehensive view helps organizations identify inefficiencies and areas for improvement within operations | Focuses solely on customer interactions and perceptions. It does not delve into the internal processes of the organization but rather emphasizes how customers feel at each stage of their journey |

| Orientation | Organization-centric | Customer-centric. |

| When to use | When customer experience is already well understood, and the need is to optimize internal processes and delivery. | To understand how customers are experiencing what is offered. |

Sources

1. “Share of economic sectors in the global gross domestic product (GDP) from 2012 to 2022”. Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/256563/share-of-economic-sectors-in-the-global-gross-domestic-product/. Accessed 15 Apr 2025.

2. “Which Industries See the Highest (and Lowest) Customer Satisfaction Levels?”. Hubspot, https://blog.hubspot.com/service/customer-satisfaction-levels-by-industry#best-and-worst-satisfaction-levels. Accessed 15 Apr 2025.

3. “Services Marketing Integrating Customer Focus Across the Firm”. Valarie A. Zeithaml, Mary Jo Bitner and Dwayne Gremler, https://www.amazon.com/Services-Marketing-Integrating-Customer-Across/dp/0078112109. Accessed 15 Apr 2025.

4. “Designing Services That Deliver”. G. Lynn Shostack (HBR), https://hbr.org/1984/01/designing-services-that-deliver. Accessed 15 Apr 2025.

5. “Multilevel Service Design: From Customer Value Constellation to Service Experience Blueprint”. Lia Patrício, Raymond P. Fisk, João Falcão e Cunha, and Larry Constantine., https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235818398_Multilevel_Service_Design_From_Customer_Value_Constellation_to_Service_Experience_Blueprint. Accessed 17 Apr 2025.

6. “Marketing: Who Are Your Actual Customers?”. Insights by Stanford Business, https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/marketing-who-are-your-actual-customers. Accessed 18 Apr 2025.

7. “A Guide to Service Blueprinting”. Nick Remis and the Adaptive Path Team at Capital One, https://www.dga.or.th/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/file_26e487aea69af163911dc4f6e6b8abd4.pdf. Accessed 15 Apr 2025.

8. “Blueprinting the Service Company: Managing Service Processes Efficiently”. Sabine Fließ and Michael Kleinaltenkamp, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222515477_Blueprinting_the_Service_Company_Managing_Service_Processes_Efficiently. Accessed 19 Apr 2025.

9. “Customer Journey Map (CJM)”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/customer-journey-map/. Accessed 19 Apr 2025.

10. “The difference between a journey map and a service blueprint”. Morgan Miller, https://blog.practicalservicedesign.com/the-difference-between-a-journey-map-and-a-service-blueprint-31a6e24c4a6c. Accessed 19 Apr 2025.

11. “U.S. Customer Satisfaction Growth Stagnates”. American Customer Satisfaction Index, https://theacsi.org/the-acsi-difference/us-overall-customer-satisfaction/. Accessed 15 Apr 2025.