The ancient Greek poet Archilochus of Paros wrote, “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” The Hedgehog Concept takes this and applies it to the world of business.

It categorizes businesses into two types – the first are like foxes who know many things, are very cunning, and devise a myriad of complex strategies to launch sneak attacks on the hedgehogs. The second is like hedgehogs who know just one simple but crucial thing – rolling up into a perfect little ball of sharp spikes and winning over the fox.

The Hedgehog Concept was developed by Jim Collins, who set out to discover what made some companies vastly outperform the industry while delivering exceptional results over prolonged periods. The companies that Jim studied had delivered returns of over three times the market average for over 15 years.

Jim’s five-year quest yielded many insights, both surprising and contrary to conventional wisdom and uncovered a framework of ideas for organizations to go from being good to great – one of which is the Hedgehog Concept. While this article discusses the Hedgehog Concept, other frameworks that Jim uncovered can be found in his book “Good to Great” [1].

What is the Hedgehog Concept

The Hedgehog Concept can be used as a strategy formulation tool to bring clarity in what to do and what not to do as a business. It is about reducing all challenges and dilemmas into a single simplistic hedgehog idea.

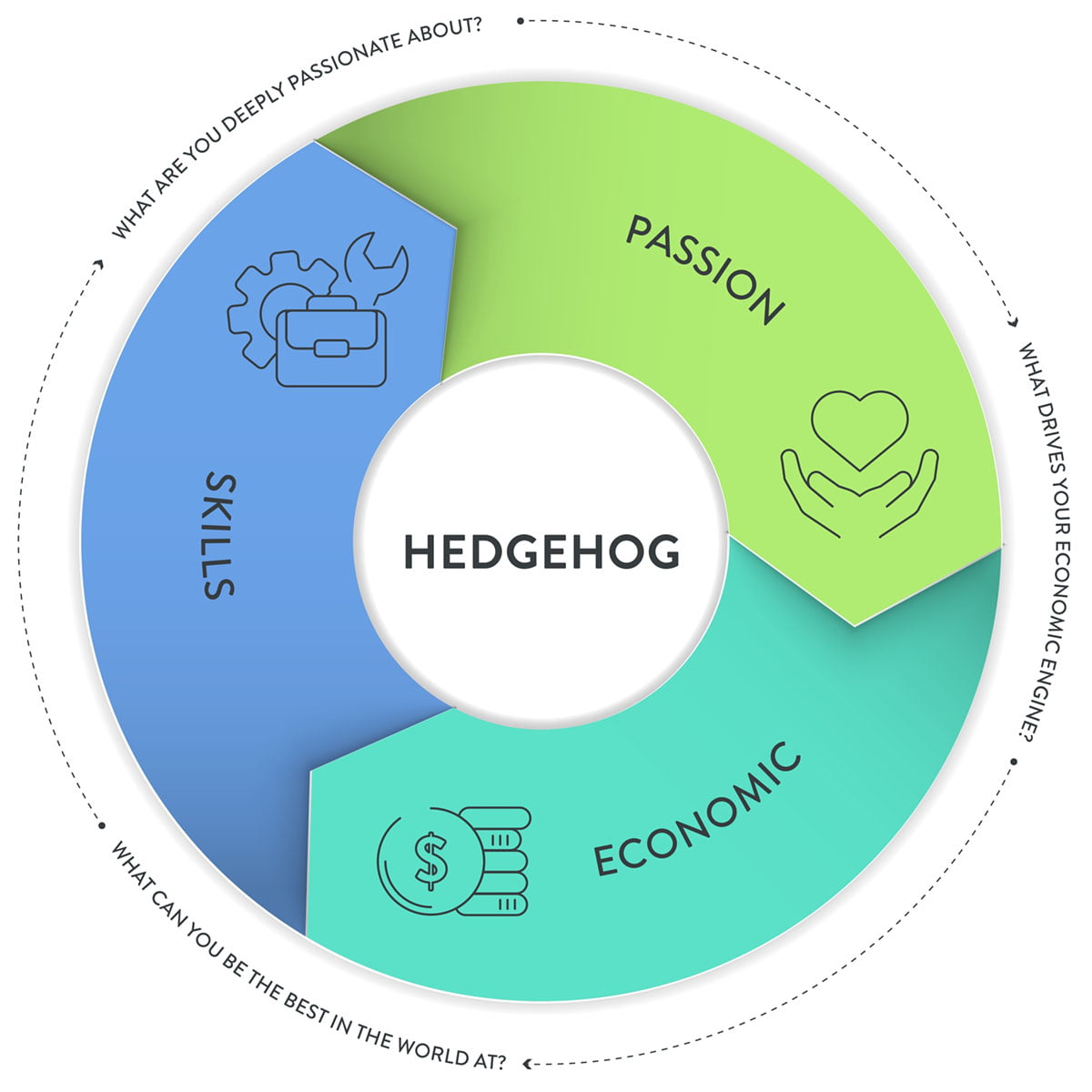

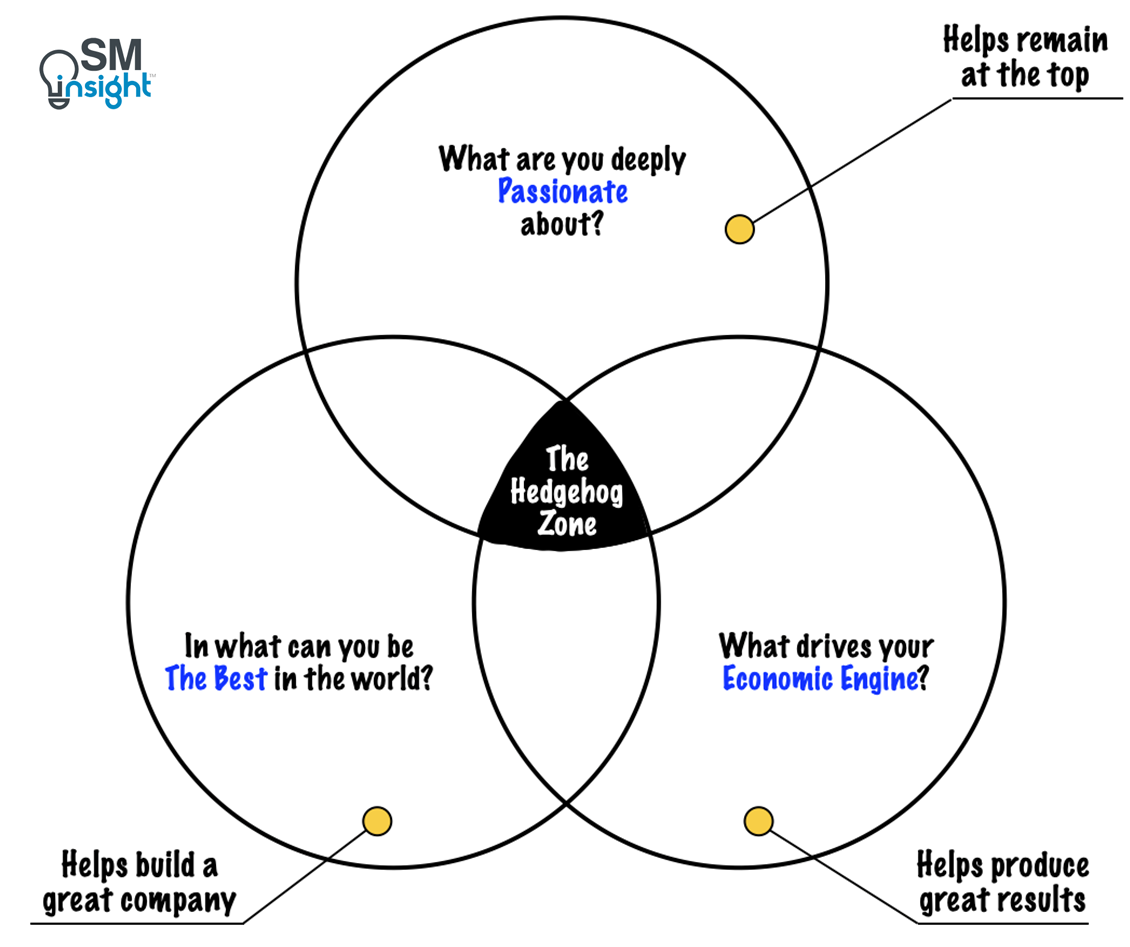

Two things are central to the Hedgehog Concept: a strategy founded on a deep understanding of the three dimensions (being the best, finding economic logic and discovering passion: see illustration) and translating that understanding into a simple crystalline concept which can guide all organizational efforts:

In what can you be the best in the world?

Every organization possesses unique strengths and can truly excel in certain areas. At the same time, there are areas where an organization simply cannot win. The key is to know where to play.

This can be tricky because what an organization can do best is not necessarily the same as its core competence. Conversely, the areas where it could be the best in the world could be those in which it isn’t even engaged.

For example, in the mid-1960s, pharmaceutical companies Abbott Laboratories [2] and Upjohn [3] were both identical in terms of revenue, profits and product lines and equally lagged behind the rest of the pharmaceutical industry. However, by the mid-1970s, Abbott went on to produce cumulative returns four times the market and five-and-a-half times Upjohn’s over the next fifteen years.

The crucial difference – Abbott developed a Hedgehog Concept based on what it could be the best at while Upjohn did not. Abbott realized it had lost the opportunity to become the best pharmaceutical company (its area of core competence) due to years of neglected research and development. Hence, Abbott pivoted its business to hospital nutritional products and diagnostic devices in which it eventually excelled.

Organizations that apply the Hedgehog Concept must understand one subtle yet crucial distinction – “being the best in the world” is not a goal, a strategy, or an intention. It is about developing a deep understanding with sharp insight and egoless clarity on what an organization can do best. It is just as important to know what an organization cannot be the best at.

Companies that get this right build a severe standard of excellence and allocate resources to those few arenas where they could potentially be the best. Following are some examples of companies that built great businesses with a deep understanding of what they were best at:

| Company (Industry) | What it could be the best at |

|---|---|

| Walgreens (Pharmacy chain) | Realized that it was not just a drugstore but also a convenience store. Moved to prime locations and made extensive investments in technology to create one giant “corner pharmacy.” |

| Circuit City (Consumer electronics retail) | In the early 1980s, Circuit City saw that it could become the McDonald’s of big-ticket retail and operate a geographically dispersed system by remote control. It successfully applied the “4-S” model to big-ticket retail (service, selection, savings, satisfaction) |

| Fannie Mae (Financial Services) | Realized that it could be the best capital markets player in mortgages because it possessed a unique ability to access risk in mortgage-related securities |

| Gillette (Safety razors and personal care) | Realized that it could be the best at building premier global brands of daily necessities that require sophisticated manufacturing technology |

| Kimberly-Clark (Paper-based consumer products) | Realized that it had a latent skill of creating category-killing brands in paper-based products where the name of the product became synonymous with the name of the category (e.g., Kleenex). |

| Philip Morris (Tobacco products) | Realized that it could become the best tobacco company in the world. Built loyalty in cigarettes, and later in other “sinful” products (beer, tobacco, chocolate, coffee) and food products. |

What drives your economic engine?

An organization does not need to be in a great industry to produce great results, but it is important to have a great economic engine. It must have a piercing insight into how to generate robust and sustained cash flow and do it profitably and effectively.

To do this, it must discover the single most effective measure (known as “profit-per-x”) that has the greatest impact on its economics. This helps accurately track improvements to the bottom line and guides actions.

Consider Walgreens, for example, which is the second-largest American pharmacy chain. Walgreens uses profit per customer visited as its key metric, which contrasts with the industry standard metric of profit per store.

Guided by this measure, Walgreens chose a unique approach to growth and profitability. Instead of reducing the number of stores and opting for less expensive locations, it prioritized customer convenience. By strategically placing its stores in prime locations, it was able to attract more customers and elevate its profit per customer. This unconventional strategy resulted in a significant boost to the company’s overall profitability.

Choosing profit-per-x, or a single denominator that accurately reflects success can be hard for most companies as such a measure is often subtle and unobvious. However, it is the process of choosing that forces a deeper understanding of the key drivers of the economic engine and stimulates intense dialogue and debate.

Shown below are economic denominators used by companies in the past that led them to go from being good to great and deliver spectacular results [1]:

| Company (Industry) | Previous metric | Shifted to |

|---|---|---|

| Abbott (Pharmaceuticals) | Profit per product line | Profit per employee – to align with the idea of contributing to cost-effective health care. |

| Circuit City (Consumer electronics retail) | Profit per store | Profit per region – to reflect local economies of scale. Regional grouping drove Circuit City’s economics beyond silos. |

| Fannie Mae (Financial Services) | Profit per mortgage | Profit per mortgage risk level – to reflect the fundamental insight that managing interest risk reduces dependence on the direction of interest rates. |

| Gillette (Safety razors and personal care) | Profit per division | Profit per customer – to reflect the economic power of repeat purchases |

| Kimberly-Clark (Paper-based consumer products) | Profit per fixed asset (mills) | Profit per consumer – to counter cyclic effects and accurately reflect profits in both good and bad times. |

| Philip Morris (Tobacco products) | Per sales region | Per global brand category – to reflect the understanding that the key to success lies in brands that could have global power. |

What are you deeply passionate about?

Passion is the third circle in the Hedgehog Concept which, though seemingly odd, must be an integral part of the strategic framework. Companies cannot manufacture passion or motivate people to feel passionate. It requires conscious efforts to discover what ignites the passions of those who work for the company.

Unfortunately, the challenge for leaders is that there is no formal management theory for how to build, leverage, and measure the level of passion in employees. It essentially falls into that ambiguous category of “you’ll know it when you see it.” [4].

Studies show that great companies did not choose to become passionate about what they are doing, rather they went the other way and chose to do things that they were passionate about.

For example, in the 90s, Gillette could safely fight a low-margin battle with disposable razors. But it instead chose to build sophisticated, relatively expensive shaving systems like the Sensor Excel and Mach 3. The move was triggered in large part because Gillette executives couldn’t get excited about cheap disposable razors.

Gillette was never content with merely having an innovative product. Despite Sensor Excel’s success, Gillette invested close to a billion dollars in the development and marketing of the Mach 3 shaving system – a blend of cutting-edge technology with relentless consumer testing that took seven years to develop. By 2000, the company enjoyed a 72% market share in both the U.S. and Europe [5].

For many companies, the passion does not necessarily have to be about the mechanics of the business. It could equally be about what the company stands for.

For example, few bank executives could be passionate about the paperwork process of packaging loans, but they can be highly motivated to help people of all classes, backgrounds, and races realize the dream of owning a home.

What matters is to have a deep and genuine passion regardless of whether it is about what the organisation does or what it stands for.

The difference between foxes and hedgehogs

Companies that have internalized the Hedgehog Concept perceive their world to be simple and clear while the foxes (those who don’t) continue to see their world as complex and shrouded in mist. This is mainly due to the following reasons:

- Foxes fail to ask the right questions while hedgehogs are forced by the three circles to question the basics and be in a position where they stand to win.

- The goals and strategies of hedgehogs are shaped by a deeper understanding of their reality while foxes let bravado direct their actions.

- Because foxes are in a mindless pursuit of growth, they see size as a measure of success and venture into any area where they spot a growth potential. Their efforts and focus are thus dispersed, leading to sub-optimal results.

Hedgehogs, in contrast, build their business around a simple, crystalline understanding of their strength, make consistent progress, and build momentum over time. Despite growth not being their primary goal, hedgehogs have shown sustained, profitable growth far greater than the foxes that made growth their mantra.

How to become a hedgehog

Despite its vital importance, attempting to adopt the Hedgehog Concept in a hurry can prove to be a terrible mistake. This is because getting it right is extremely difficult and takes years. On average, companies have taken four years to discover their Hedgehog Concept [1].

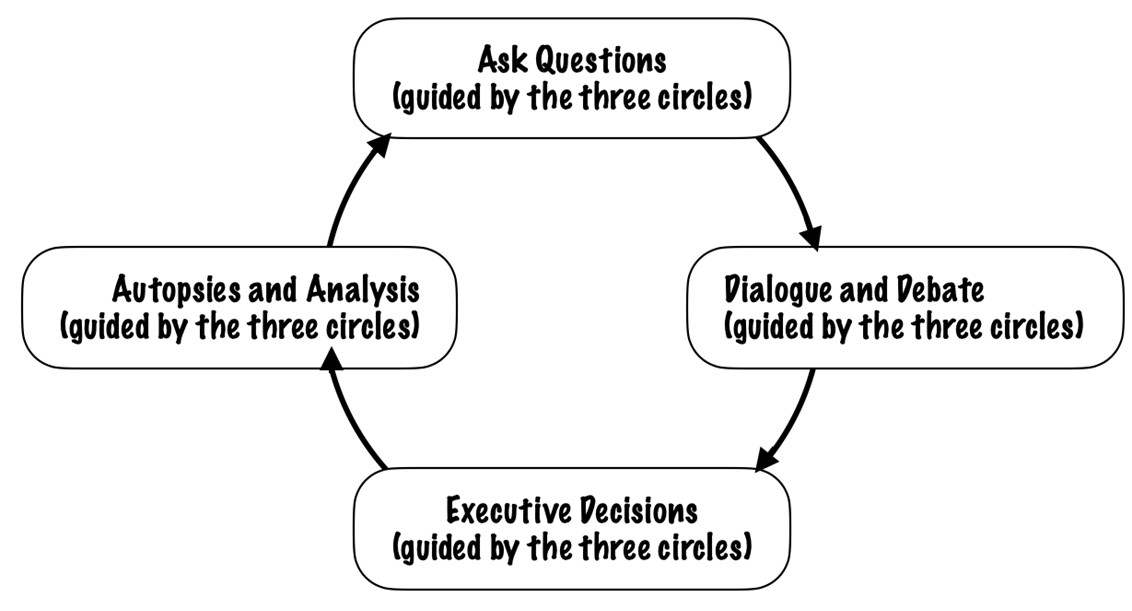

The process is inherently iterative and requires getting the right people engaged in vigorous dialogue and debate over brutal facts and questions posed by the three circles. Author Jim Collins suggests a four-stage cycle iterative cycle that organizations can use to gain an in-depth understanding:

To iterate over these steps, an organization must first build a council – a group of key people who can address the vital issues and decisions facing the organisation. This council must have the following characteristics:

- It must exist to gain a deeper understanding of the important issues facing the organization.

- It must be assembled and used by the leading executive (CEO) and must typically consist of between five to twelve members.

- Members must have the ability to argue and debate in search of understanding. The intention should not be to win an argument or make a point.

- Mutual respect is crucial.

- While each member may have a range of perspectives, every member must bring deep knowledge about some aspect of the organization or its environment.

- It must have a mix of both management as well as executive members.

- It must be a standing body and not an ad-hoc committee assembled for a specific project.

- The members must meet at least once per quarter.

- It is not important to seek consensus. The goal is to come up with intelligent viewpoints while final decisions on implementation can be taken by top executive.

- The council must be an informal body not listed in the organizational chart or any formal documents.

By following the above guidelines, most companies, no matter how awful at the start of the process, can eventually discover how to become a Hedgehog.

Sources

1. “Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap and Others Don’t”. Jim Collins, https://www.amazon.com/Good-Great-Some-Companies-Others/dp/0066620996. Accessed 26 Jul 2024.

2. “About ABBOTT”. ABBOTT, https://www.abbott.com/about-abbott.html. Accessed 27 Jul 2024.

3. “The Upjohn Company”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upjohn. Accessed 27 Jul 2023.

4. “How to Build a Passionate Company”. Jim Whitehurst – Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2016/02/how-to-build-a-passionate-company. Accessed 28 Jul 2024.

5. “MACH 3: Anatomy of Gillette’s Latest Global Launch”. PWC – strategy+business, https://www.strategy-business.com/article/16651. Accessed 28 Jul 2024.