Organizational design (OD) is a complex undertaking with numerous steps and choices. Research suggests that only 10% of companies successfully align strategy with organizational design [1]. A recent McKinsey survey of over 2,500 business leaders worldwide found nearly 70% saw their organizations as overly complex and inefficient [2].

A generation ago, OD was a rare affair—executives dealt with it only a few times during their careers. Today, economic volatility, geopolitical instability, and the rapid pace of technology have put organizations in a nearly permanent state of flux, necessitating the need to adapt and stay agile to be competitive.

Poor organizational design is a primary cause of failure when leaders attempt to translate strategy into results. Early decisions in the process can constrain options, limit exploration, and eliminate alternatives. To address these challenges, OD practitioners have developed various organizational change and development models.

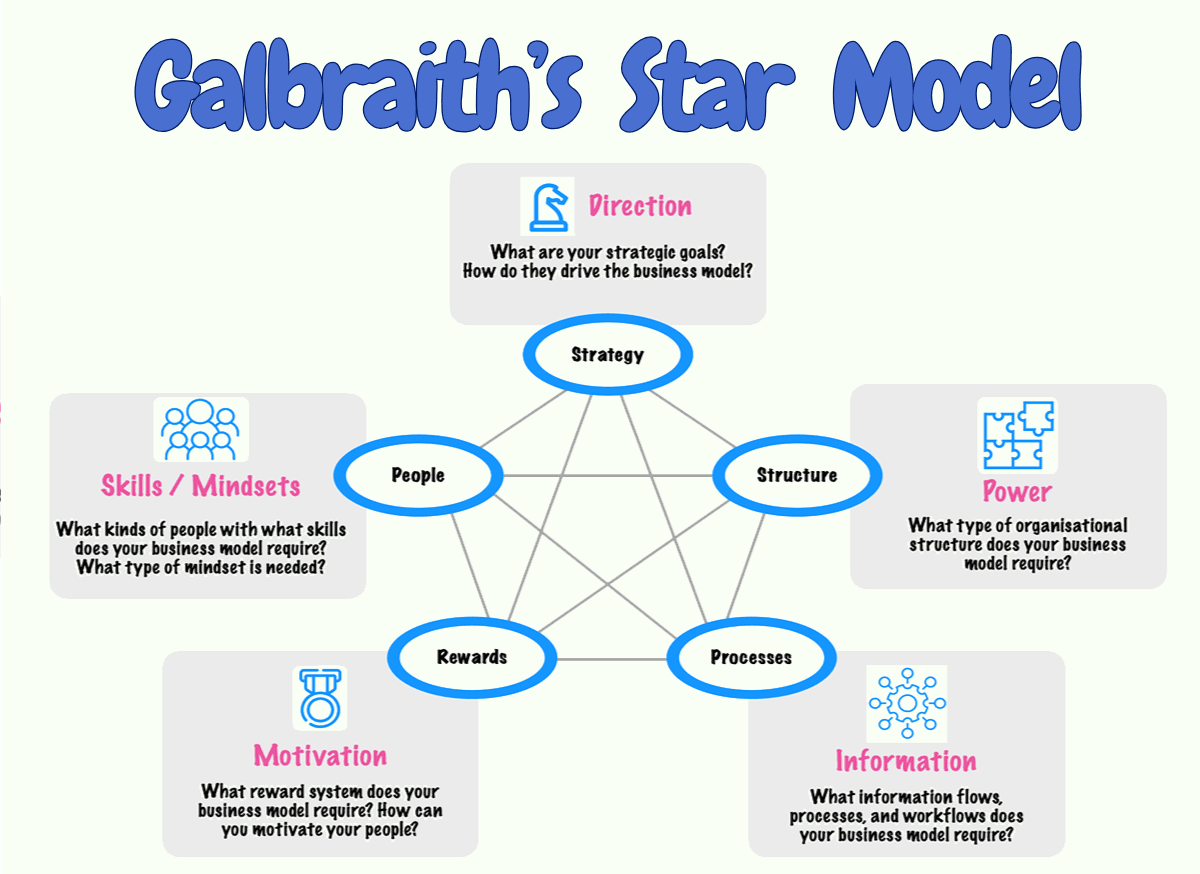

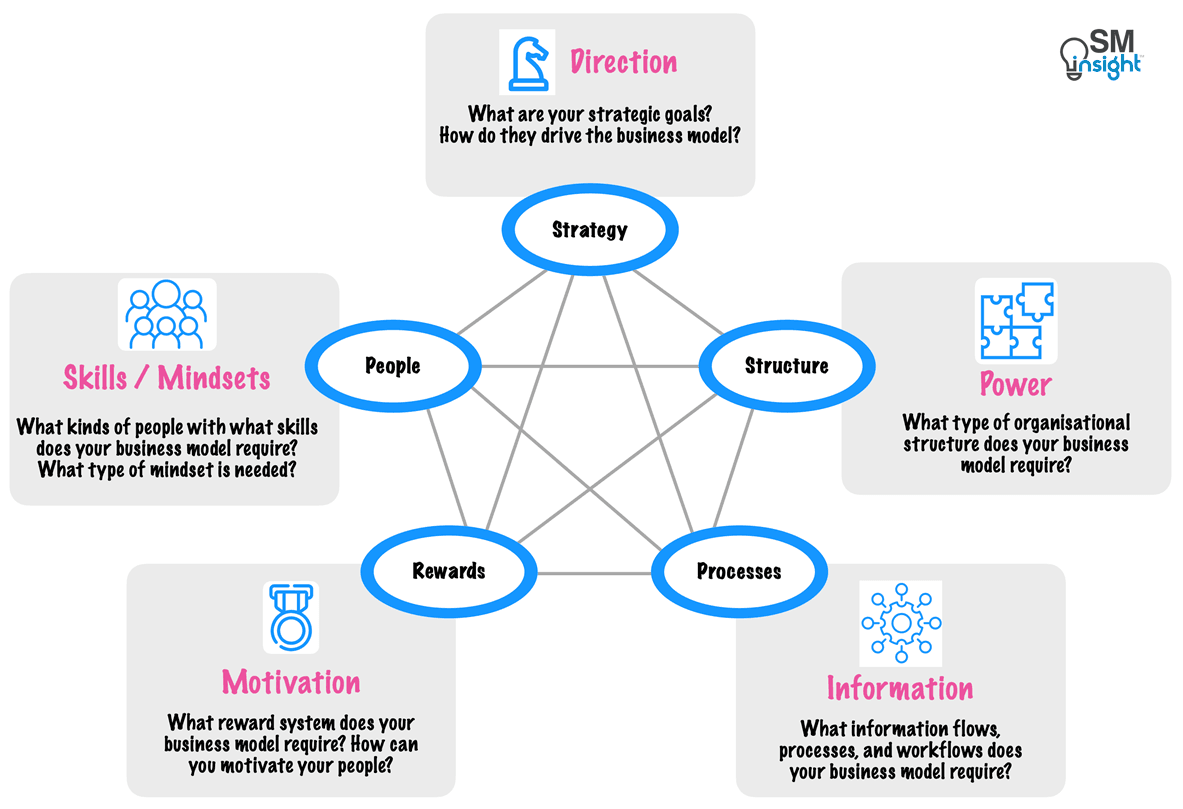

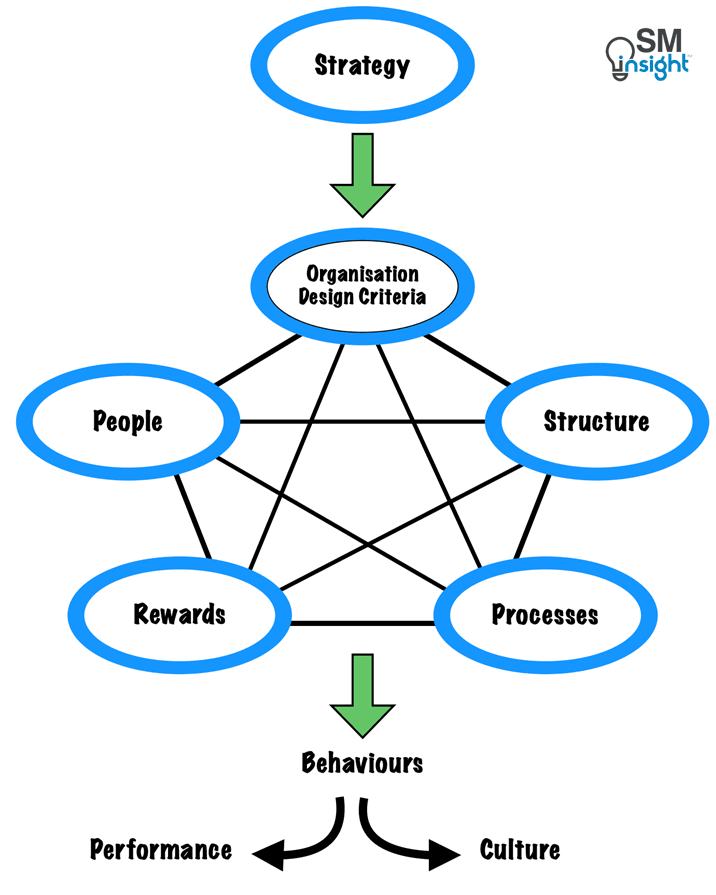

The Galbraith’s Star Model™ is one of the most enduring and widely recognized organizational design and change models. It serves as a framework for organization design, emphasizing the alignment of five key strategies: Strategy, Structure, Processes, People, and Rewards.

Despite being over 60 years old, the Star Model is still popular and has extended its influence to other prominent models, including McKinsey’s 7-S, Mintzberg’s Pentagon, and Nadler and Tushman’s Congruence Model.

Five Levers of the Galbraith’s Star Model

Galbraith’s Star Model is designed on the premise that organization design is the responsibility of the leadership. At its core, the Star Model is a prescriptive framework comprising five “levers” or design policies that the organization designer can change or manipulate.

The idea stems from the belief that organizations are collections of individuals who process information. Thus, managers can shape employee behavior and culture by changing how power is held and manifested, how information is processed and moves through the organization, how people are motivated, measured, and compensated, and what kind of people sit in particular roles and get promoted.

By aligning these five “levers” with each other, the Star Model aims to achieve maximum organizational effectiveness.

Strategy

Strategy is where organizational change begins. It sets the company’s direction, guiding what the organization must produce, where it should play and be active, and how it will be profitable. In short, strategy is the company’s formula for winning.

A company’s strategy derives from the leadership’s understanding of the external factors, such as competitors, suppliers, customers, and emerging technologies, that affect the firm, combined with their understanding of the organization’s strengths in relation to those factors.

Because strategy sets the framework for all subsequent design decisions, it occupies the top of the Star Model. It allows leaders to project a picture of the future—where the organization must go and what it should look like when it gets there.

Three key activities take place simultaneously in the strategy phase of the Star Model:

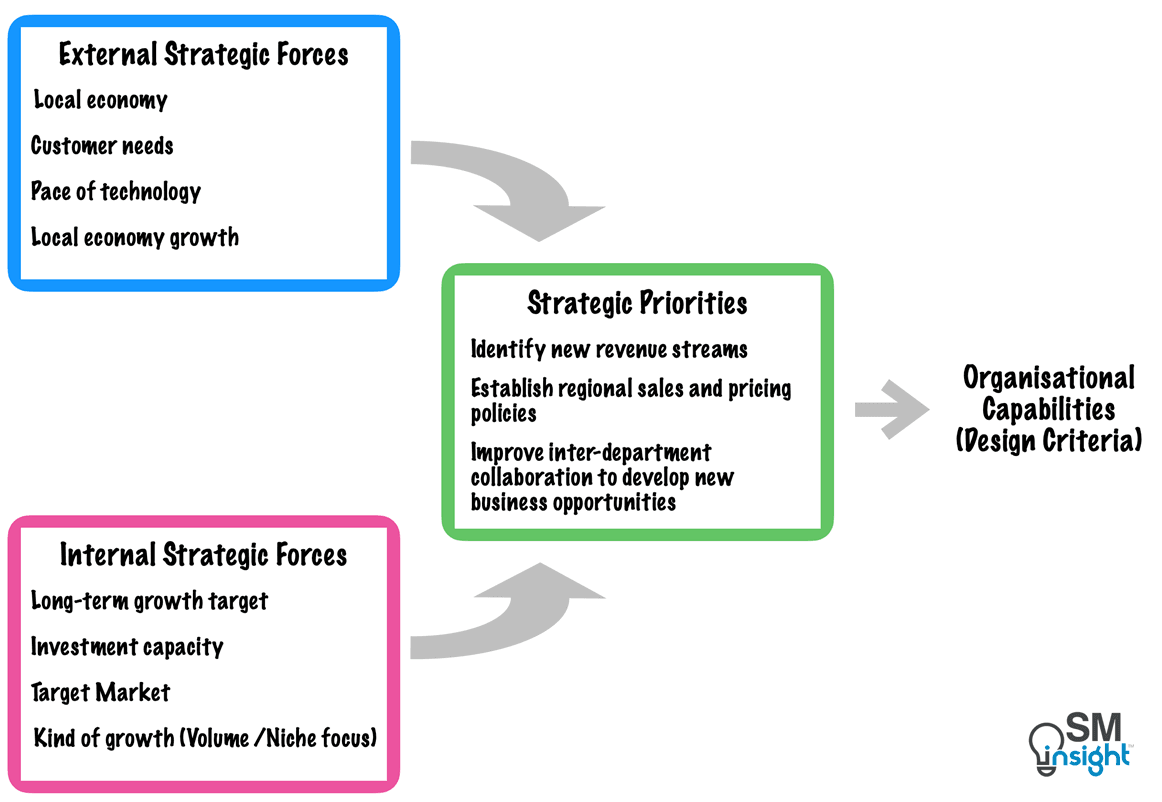

1. Translating The Strategy Into Design Criteria

Design criteria are the organizational capabilities that allow a business to achieve its strategy. This includes skills, processes, technologies, and human abilities that create a competitive advantage. Different strategies require different organizational capabilities and, therefore, different organizational designs.

There are three steps in translating strategy into design criteria:

Identifying Success Indicators

Success indicators define the desired future state in terms of business outcomes and specify how they will be measured. In short, what business results must the design achieve?

One approach to developing success indicators is to imagine a future scenario where the company is highlighted as a success story in a business article. The company is now a benchmark for others in the industry. With that vision in mind, ask the following questions:

- What does the article say the company is successful at doing?

- Why is it successful? What is it that works so well?

- What has changed?

- What value does it provide to customers and employees? How would they describe the company?

Answer these questions individually and discuss as a team to agree on the outcomes that indicate organizational success. Quantify wherever possible. This exercise aligns the executive team around the shared goals and creates a platform for redesign.

Understanding The Organization’s Value Proposition

Value Proposition is a unique combination of qualities a strategy aims to exploit. There are three approaches to how an organization differentiates itself: product excellence, operational efficiency, and customer-centric focus. Each demands a distinct set of qualities to achieve success.

A product-focused company will have a high tolerance for mistakes and experimentation, while an operations-focused company will focus on standardization, where efficiency will be rewarded over creativity.

Understanding the core value propositionis fundamental to aligning the rest of the organization to support it.

Determining The Design Criteria

What organizational capabilities must the design help the organization build? Ask the following questions to understand the organization’s strategic focus:

- Are we primarily product-, operations-, or customer-centric?

- Why? What is the rationale?

- What are our existing strengths?

- What has changed in the environment?

- What challenges are we facing due to changes in markets/customers/ competitors?

- What are our priorities?

- What opportunities do we need to pursue?

- What changes in the marketplace do we need to respond to?

Individually review the list of organizational capabilities and identify what is missing. Compare priorities as a group and agree on the most critical capabilities.

2. Clarifying Limits and Assumptions

Limits define what is included in the design process and what is not. Without them, effort can be wasted generating recommendations that won’t be implemented. They function like the brakes in a car: their primary function is not to slow down but to allow faster movement with confidence.

3. Assessing The Current State

A current state assessment provides a snapshot of the strengths and weaknesses of the organization, serving as a scan that reflects the broader perspective on what is and what is not working today. It also provides an early glimpse of potential implementation barriers.

Employees are often the richest source of data for current state assessment. Interviews, focus groups, and/or surveys are the best assessment methods. When conducting assessments, it is essential to ensure the following:

- Representative sample: chosen employees must be from all levels and areas (functions, locations, business lines, etc.). This ensures no one level or department skews the findings.

- Numbers: enough people should participate to allow trends to emerge and to ensure the opinions of a few do not distort the data.

- Knowledge: participants should be high performers who know the organization well and are not afraid to express their opinions. Choose people who have worked across organizational lines, have experience dealing with other departments, and have at least some customer contact, either internal or external.

Designing the Structure

Structure refers to the formal way in which people and work are grouped into defined units. It determines the placement of power and authority within the organization. There are five steps to designing a structure:

1. Selecting a Structure

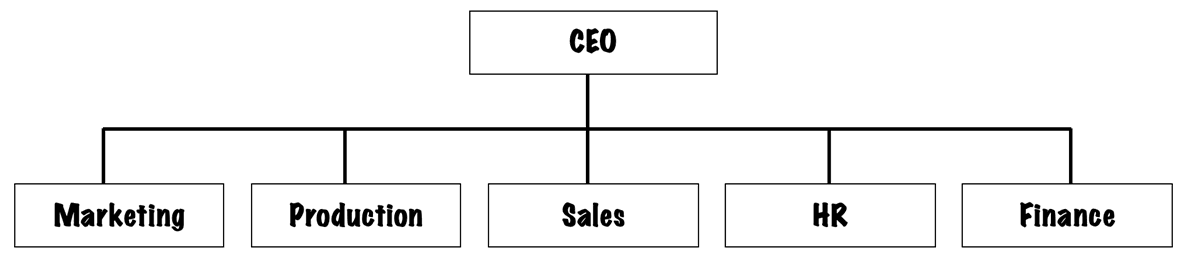

An organization can be structured in five primary ways: (1) Function, (2) Geography, (3) Product, (4) Customer, and (5) Front-back hybrid.

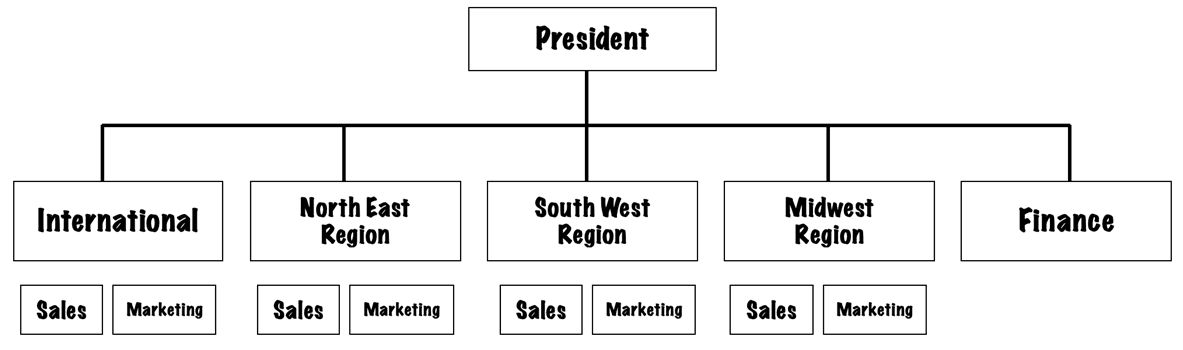

A Functional Structure is organized around activities or functions (see image).

It is best suited for companies that have a single line of business, are small, require common standards, and have a core capability that requires deep expertise in one or more areas. Such companies don’t have a diverse product line, and the pace of product development is not critical.

Manufacturing companies often benefit from a functional structure that allows specialization. Large tech companies like Apple and Amazon also utilize this structure to group employees based on technical skills and roles.

A Geographic Structure is organized around physical locations such as states, countries, or regions.

This is ideal for companies with high transportation costs, those delivering on-site services, requiring proximity to customers for delivery/support, or looking to establish a local presence and build stronger connections with their customer base. Global consulting and law firms typically follow a geographical structure.

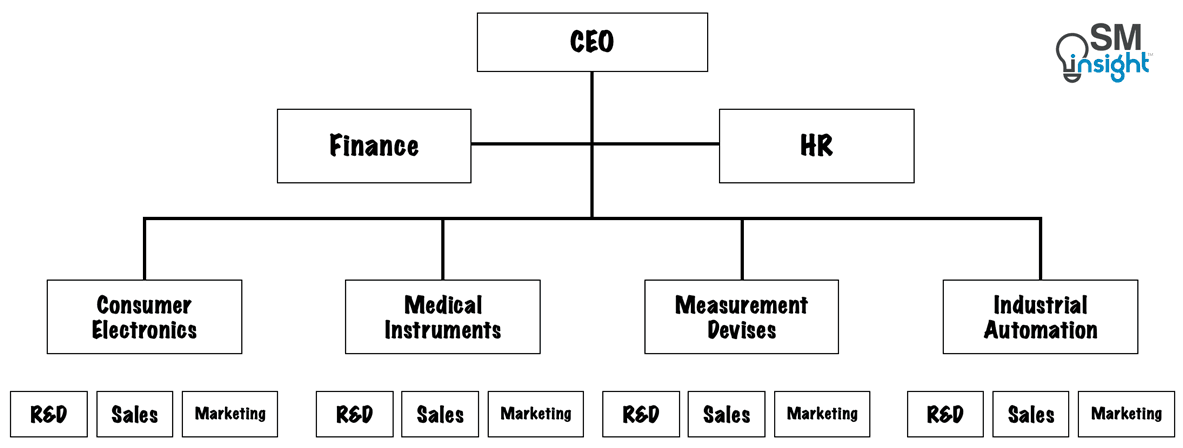

A Product Structure is organized into product divisions, each with its functional structure to support its products.

This works best for companies that compete on product features or first-to-market strategies, develop multiple products for different market segments, create products with short life cycles (where development pace is critical), or have the scale to efficiently duplicate functions.

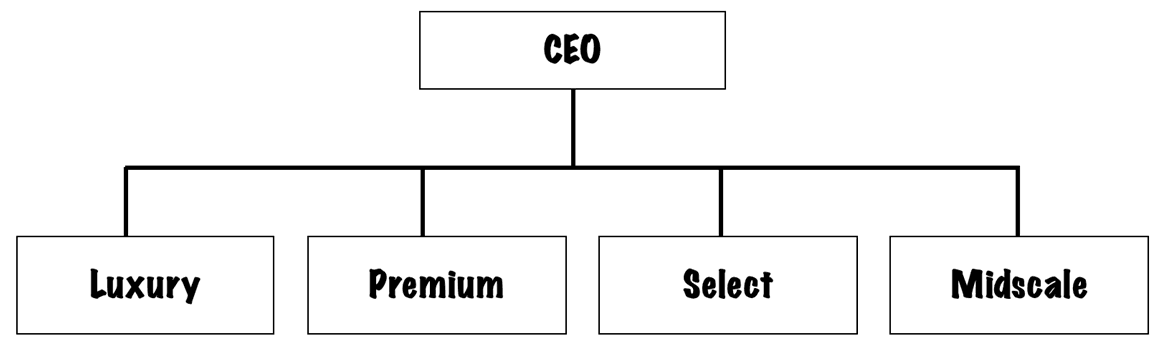

A Customer Structure is organized around market segments such as client groups, industries, or population groups. It is best suited for market segments where buyers have considerable strength and influence.

For example, large hospitality companies, such as Marriott, can benefit by structuring their brands into Luxury, Premium, Select, and Midscale based on customer spending.

It allows companies to leverage customer knowledge to provide an advantage and compete based on rapid customer service and cycle times. However, this structure also requires scale to duplicate functions.

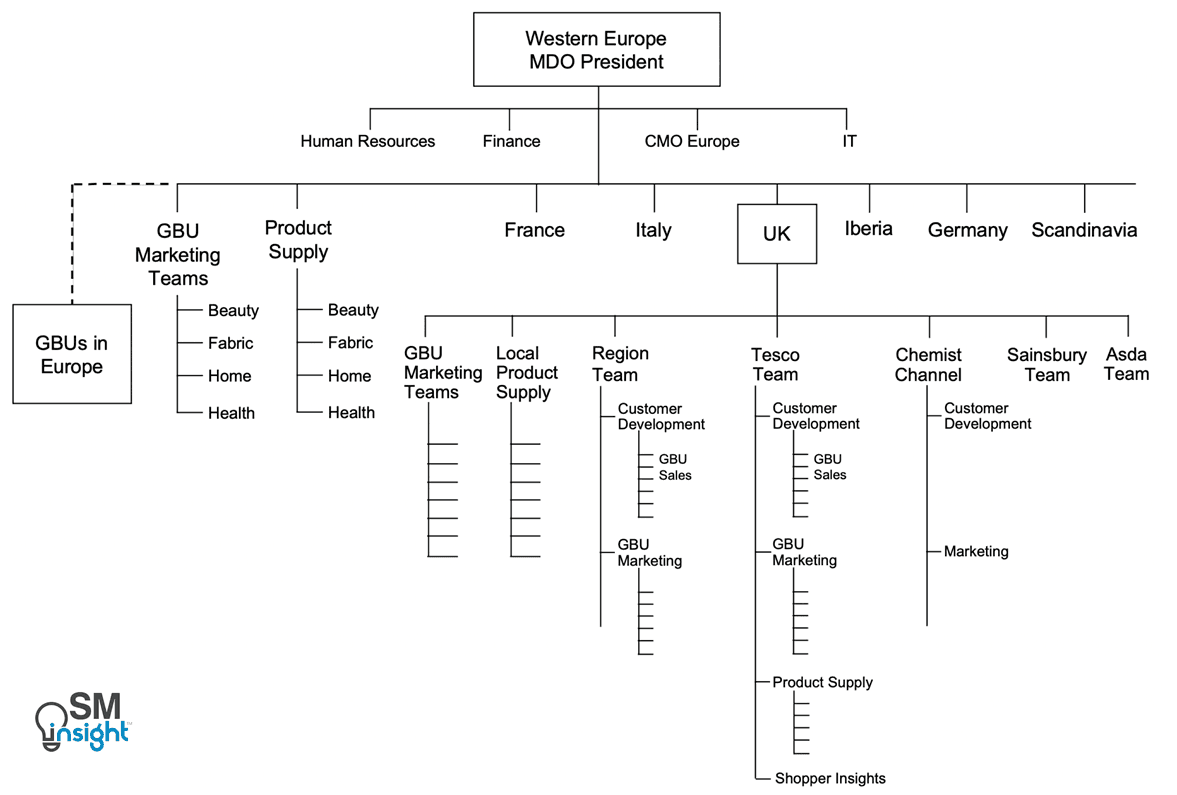

A front-back hybrid structure combines elements of the product and the customer structure, allowing for product excellence at the back end while increasing customer satisfaction at the front end [7].

The front-back hybrid structure is best for large organizations that are:

- Have multiple product lines and market segments.

- Serve global customers and must have cross-border coordination.

- Need to maximize both customer and product excellence.

- Have managers skilled in managing complexity.

The table below compares the advantages and disadvantages of each of the structures [8]:

| Structure | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|

| Functional | Knowledge sharing within functional groups, promotes specialization, leverage on vendors, economy of scale, standardization. | Not suitable for diverse products and services, creates barriers when processes are cross-functional. |

| Geographic | Local focus | Mobilization and sharing of resources across locations is slow. |

| Product | Shorter product development life cycle, focus on product excellence, broad operating freedom. | Divergence – each division has its own focus, duplication, lost economy of scale, multiple customer touchpoints. |

| Customer | Supports customization, easier to build relationships, makes moving from product to solutions easier. | Divergence, duplication, scale |

| Front-back hybrid | Single point of interface for customers, cross selling, value added systems and solutions, product focus, multiple distribution channels. | Contention over resources, disagreement over prices and customer needs, marketing ownership, conflicting metrics, complexity in information and accounting. |

2. Define Organization Roles

Roles can change even if organizational components retain the same names. This could be for a business unit, a function, or a type of job. Role alignment has three steps: (1) definition, (2) interface, and (3) boundaries.

Role Definition

Role definition clarifies what is unique and different to each role and the value it is expected to add. At a minimum, role definition must include outcomes and responsibilities.

Outcomes are end states to be achieved or results to be attained. Whenever possible, they must include the time frames and measures. For example, “Grow market share to 10% within twelve months.” Focus on those outcomes that distinguish the role from others. Emphasize what is unique.

Responsibilities are tasks that close the gap between the current and the desired state (outcomes). While it is tempting to jump to the tasks that need to be performed, it is important to determine the priority of problems and obstacles. The tasks then become the means to address the problems and seize the opportunities.

Ask the following questions:

- What are the highest-priority gaps?

- What plans must be developed, actions must be taken, and resources must be acquired to close the gap?

- What steps should be followed to understand and reach the needed results?

- How would an “expert” address these problems and opportunities?

Interface

Roles in an organization are interdependent and have points of interface with mutual expectations. These “gray areas” require collaboration across roles to accomplish work. If not defined and managed, they become visible to the customer, signaling that the organization does not work as an integrated team.

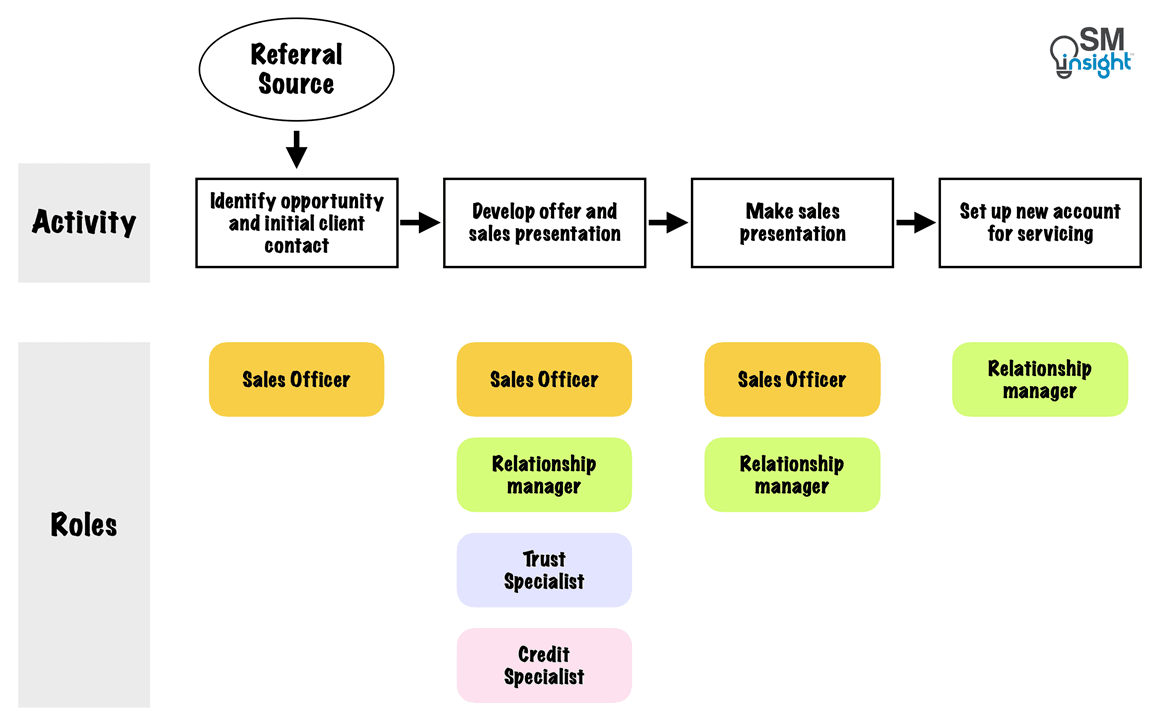

One way to identify interdependencies is to start from the perspective of the central business processes and chart out blocks of work and handoffs as shown:

Boundaries

Organizational conflicts occur when people have differing views about authority over decision-making and responsibility. This is unproductive and wastes energy and time.

The RACI responsibility charting matrix helps identify where one role ends and another begins. Critical decisions are listed on the left, and the roles are listed across the top row of the grid. For each decision, a code is assigned:

| R = Responsibility | This role has the authority and responsibility to decide. |

| A (Accountability) | This role may not make the decision but is held responsible for the outcome. |

| C = Consult | This role must be consulted and provide input before a decision is made. |

| I = Informed | This role needs to be informed about the decision after it has been made. |

The following rules must be followed when charting responsibility:

- Each decision must have an R. Someone must be responsible for the decision.

- There can only be one R given for each decision.

- Each decision must have an A. It may be the same as the R role.

- Ensure that the Cs represent a diversity of viewpoints for important decisions.

RACI occasionally includes a V, which stands for Veto, one who can block a decision. This is different from the veto power that a boss or higher-level role has—it refers here to a role that reserves the right to veto a specific decision.

V should be used sparingly. Too many Vs may indicate that responsibility is being placed in the wrong role or that trust and competence issues must be examined.

An example of a RACI matrix for a client-facing team in a private bank is shown:

| Roles | ||||

| Key Decisions | Sales Officer | Segment Leader | Relationship Manager | Sales Manager |

| Market Pursuit | R | C | I | A |

| Product pricing | R | A | C | I |

| Proposal development | A | C | C | I |

RACI is most effective when people complete it individually or in small groups and compare the differences. It is a basis for discussing overlaps and differing assumptions to avoid conflicts.

3. Testing The Structure Design

A new structure must be reality-tested for its design, considering organizational capabilities, power dynamics, workflow efficiency, e-commerce impact, complexity, and consistency. Ask the following questions:

- Does the structure meet the design criteria?

- Does the structure create power imbalances? Where does the power lie in the new organization? What roles, processes, or other mechanisms balance this new power center?

- Does the structure support the flow of work? Have units and departments been configured to facilitate a logical flow of work? Is work contained, end to end, in one unit where possible?

- Are multiple distribution channels accounted for? Do they hold equal power in the organization? How do we ensure internal competition does not distract attention from real competitors?

- Is the new organizational structure overly complex? Can the same outcomes be achieved with a simpler structure?

- Is the organizational culture congruent with the design? What cultural values or norms might be challenged by the envisioned organization?

Designing Processes

“Process” in Galbraith’s Star Model refers to a series of connected activities that

move information up, down, and across the organization. This includes networks, teams, integrative roles, and matrix structures, collectively called lateral connections, that embody the flow of information.

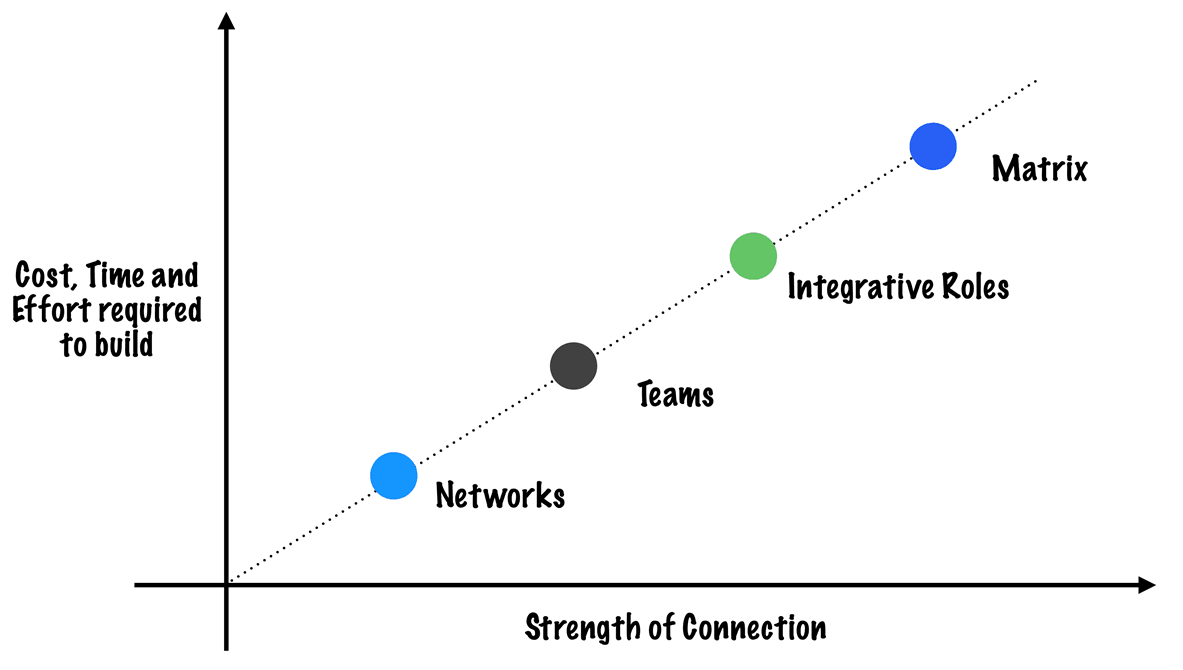

Lateral connections shape an organization’s workflow, communication, power, and decision-making. Plotted on a continuum, they would look as follows:

Networks

Networks are webs of interpersonal relationships people form and use to coordinate work informally. It is the foundation for all other lateral connections. While networks are voluntary and do occur spontaneously, their formation can be aided by:

- Co-locating people who need to work together and designing the physical space to encourage informal interaction.

- Creating communities of practice that bring together employees in different organizational units with a shared interest.

- Using meetings, retreats, and training programs to build relationships among individuals from different units.

- Rotating work assignments to bring knowledge, relationships, and culture from one unit to another and create understanding and appreciation for different organizational perspectives.

- Using technology and e-coordination to make knowledge sharing easy and help staff find others with complementary skills or interests.

Teams

Teams are cross-business structures that bring people together to work interdependently and share collective responsibility for outcomes. They can be configured around any dimension. For example, a team could be product, customer, or geography-based when the primary structure is functional.

Teams are more formal than networks; their participation is mandatory rather than voluntary, with specific accountability and expected outcomes. Teams typically require a leader or project manager, dedicated resources, senior-level sponsorship and attention. They are also costlier than networks.

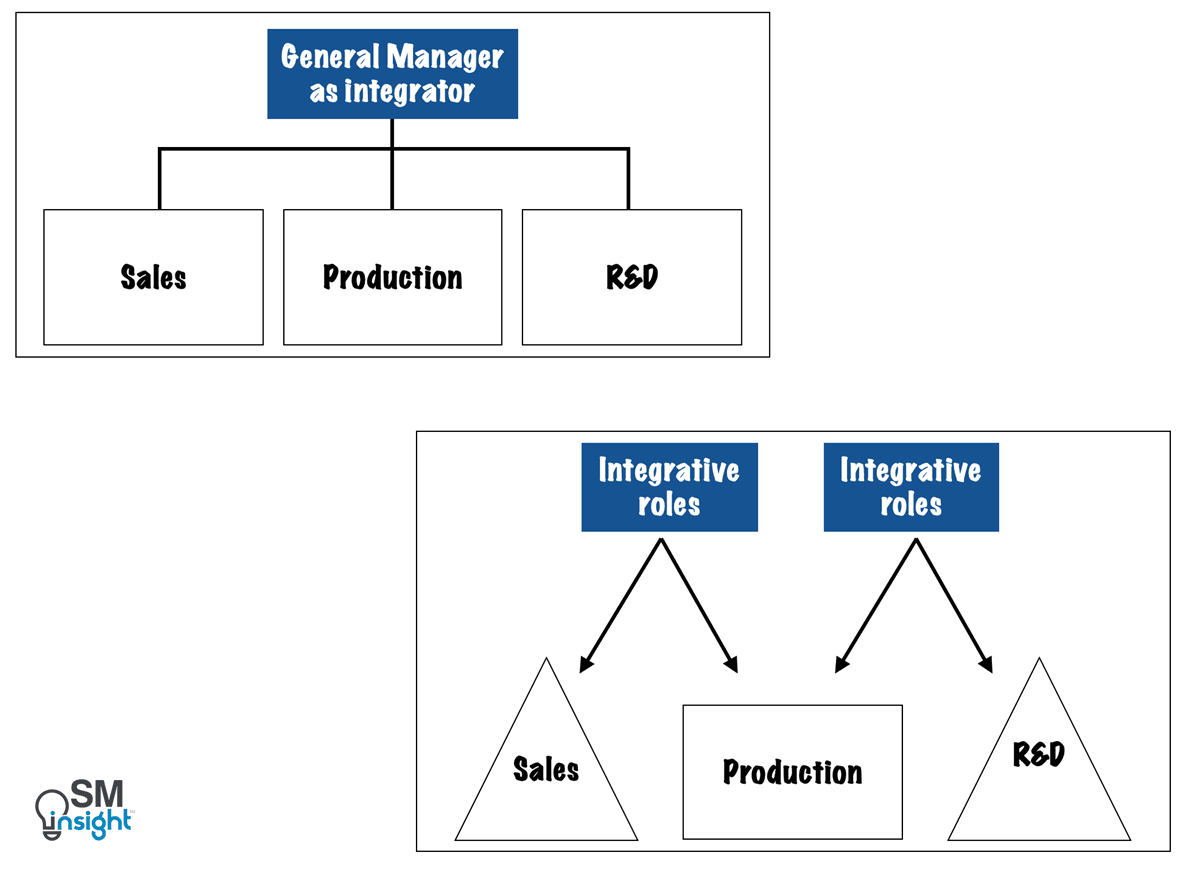

Integrative roles

An integrative role is a full-time manager charged with orchestrating work across units. This differs from a team where members remain in their business unit and devote part of their time to the team’s mission or participate for a limited period.

Those in integrative roles are accountable for results but do not directly manage the resources needed to achieve them. For success in any integrative role, four behavior characteristics are essential [9]:

- Integrators need to be seen as contributing to important decisions on the basis of their competence and knowledge rather than authority.

- Integrators must have balanced orientations and behavior patterns.

- Integrators must feel they will be rewarded for total product responsibility and not solely based on individual performance.

- Integrators must have the capacity to resolve interdepartmental conflicts and disputes.

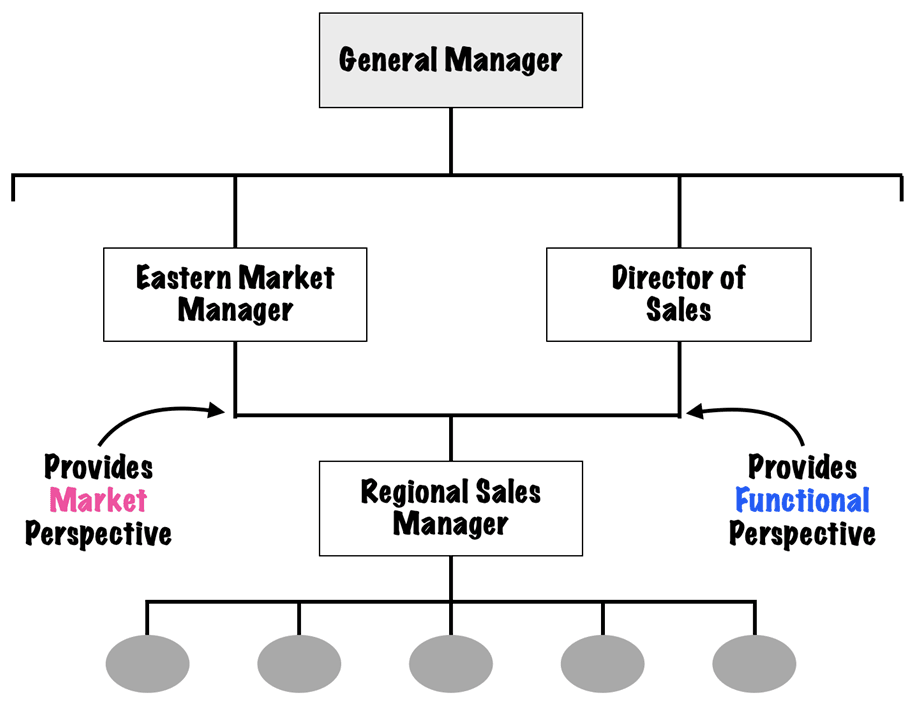

Matrix

A manager in a matrix organization has two or more upward reporting lines to bosses who each represent a different business dimension, such as product, region, or customer. The two bosses are jointly responsible for setting the manager’s objectives, supervising his work, performing his appraisal, and ensuring his development [10].

The idea behind the matrix is that lateral coordination is more easily achieved at the top of a company where executives naturally sit together, often because they are incentivized for the company’s overall well-being.

Two desired behaviors result from matrix structures:

- A simultaneous focus on multiple perspectives: matrix forces a person or unit to be responsive to two or more dimensions, improving decision quality. It allows a middle manager to make trade-offs from a “general management” perspective more quickly than if one reported through a single channel.

- More effective use of technical and specialized resources: Matrix allows for sharing expert resources without having one division or unit own them.

When considering matrix structures, one must:

- Use them sparingly: matrix should not be the default design option. It should be used only when (1) there is a major need for middle managers of different units to coordinate important business matters on a daily basis. (2) required coordination cannot be achieved through soft-wiring methods such as networks, teams, or integrative roles.

- Align the management team: subordinates in a matrix must (sometimes) reconcile conflicting directions from reporting bosses. If they aren’t easily reconciled, both bosses have to get together and resolve the matter. While this encourages healthy trade-offs and better decisions, a downside is that it introduces conflict.

- Keep it simple: matrixes become overly complex and unwieldy when there are multiple layers between the two bosses and the senior manager, who must function as a tiebreaker for disputes. A heavily matrixed organization requires dozens of people for dispute resolution, meaning operations can’t function effectively.

- Install accounting and reporting systems to support it: dual accountability induced by matrix structure requires reporting systems that allow information to be aggregated and desegregated along all matrix dimensions.

Designing Rewards

How people are measured and rewarded influences how they use their skills, knowledge, and capabilities to carry out their work. Rewards must be designed to motivate and reinforce behaviors that add value to the organization. A reward system has four components:

Metrics

Metrics are systems that identify measures and targets for enterprise, business unit, team, and individual performance. They reflect the organization’s operating assumptions. For example, if growth is the top priority, metrics emphasize growth objectives.

The design of sound metrics rests on six principles [8]:

| Principle | What it means |

|---|---|

| Breadth | Go beyond financial measures. Balance financial measures with operational indicators. Balanced Score Card [11] is a useful tool to use. |

| Criticality | Measure what’s most important – those drivers of performance that will make a significant difference if they change. |

| Time Orientation | Look backward and forward. Use lagging indicators for accuracy; use leading indicators to predict future trends. |

| Consequences | Beware of unintended consequences. Check that measures don’t drive undesirable behaviors. |

| Alignment | Avoid conflicting measures. Cascade metrics down from the top and align them among interdependent roles at each level. |

| Targets | Set targets to be challenging but not impossible. Use standards to communicate expectations and ensure equity. |

Desired Values and Behaviors

Values are the principles that a company stands for. An organization’s vision and values are the basis for defining behaviors critical to shaping the organization’s culture. However, in most cases, they become a mere exercise for management to produce statements before relegating them to the shelf. Value statements, by themselves, have little power. The key is translating these documents into a corporate compass that guides employee behavior [12].

Compensation

Compensation is a powerful tool for aligning behaviors to organizational goals. While primarily used to pay people for the time they put into the organization, compensation can also be used to acknowledge and reward past results, to improve motivation for future performance, and to retain employees.

Ask the following questions to think through the design of the compensation system:

- What are people paid for in the organization? Time? Performance? Skills and Knowledge?

- How clear are people about what their compensation represents? Are they being rewarded for past performance? Motivation for future performance? Retention?

- How aware are people of the value of their total compensation—salary, bonuses, stock, benefits, and other rewards combined? How is this communicated?

- How well do performance management and compensation systems differentiate performance? How does it ensure high performers are rewarded substantially more than average and low performers?

- To what extent does the compensation system distinguish between team versus individual contributions?

- Do people have control over the variables that affect their compensation?

- Are payouts based on objective measures of performance and contribution?

Reward and Recognition

Reward and recognition are non-monetary components that complement compensation in aligning behaviors to business outcomes. Unlike compensation systems, they don’t require significant time and investment, but they must be well-thought-out to be effective.

Although the words “reward” and “recognition” are used interchangeably (and they do have some overlap), there are some important differences.

| What It Communicates | What It Focuses On | |

|---|---|---|

| Reward | “Do this,” and you will “get that.” | Extrinsic motivations |

| Recognition | “The work you do is meaningful, and you’ve done it well.” | intrinsic motivations—positive feelings about work |

Some questions to consider in designing rewards are:

- What behaviors and actions are essential to support desired strategic outcomes?

- At what level should results and behaviors be measured and rewarded: team, department or unit, division, or company?

- How high up in the organization should results be aggregated before being rewarded?

- What level will still allow employees to feel they are being measured on the outcomes of their decisions and actions?

- Who should assess the performance on which rewards are based?

- What is the role of customers, peers, direct reports, lower-level staff, and colleagues from other departments?

- How does the organization create rigor around what can become a subjective evaluation of required behaviors?

People Practices

People practices are the collective human resources systems and policies that include selection and staffing, performance feedback and management, training, development, and careers.

When done right, this helps attract, develop, and retain top talent whose individual and collective strengths support the current direction while providing the agility to adapt and redeploy if that direction changes.

Competencies that the organization needs to select and develop include the ability to:

- View issues holistically and from cross-functional and cross-cultural perspectives.

- Negotiate and influence without formal authority or positional power.

- Build relationships and networks and skillfully work through informal channels.

- Advocate and collaborate without bullying or compromising.

- Share decision rights and resources and make joint decisions with peers.

- Exhibit flexibility and resolve conflicts.

- Manage projects with discipline.

- Make decisions in situations of ambiguity and change.

Management must model these abilities and behaviors through transparency and open communication.

Implications of the Galbraith’s Star Model

The central tenet of the Star Model rests on three core assumptions, each with implications for organizational design:

First, different organizational strategies will lead to different structures. There is no one-size-fits-all organization design. Companies must choose a design (or a combination of designs) that best meets the criteria derived from the strategy.

Second, an organization is more than just a structure. People tend to invest more time and effort into organizational structure because it affects status and power. The star model forces decision-makers to look beyond organization charts into processes, rewards, and people that are equally important.

Finally, alignment among the five policy areas of the Star Model leads to desired behaviors that shape the organization’s culture and drive performance.

Faced with negative team behaviors, declining culture, and performance drops, leaders often attempt to swap people or encourage behavioral changes. The Star Model shows these problems can be addressed fundamentally using its five levers, resulting in a sound organizational design that is also receptive to change.

Sources

1. “Design Your Organization to Match Your Strategy”. Ron Carucci and Jarrod Shappell (HBR), https://hbr.org/2022/06/design-your-organization-to-match-your-strategy. Accessed 17 May 2025.

2. “The State of Organizations 2023: Ten shifts transforming organizations”. McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/the-state-of-organizations-2023. Accessed 17 May 2025.

3. “McKinsey 7S Model”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/mckinsey-7s-model-framework/. Accessed 22 May 2025.

4. “The Structuring of Organizations”. Henry Mintzberg, https://www.amazon.com/Structuring-Organizations-Henry-Mintzberg/dp/0138552703. Accessed 22 May 2025.

5. “Congruence Model”. CIO Wiki, https://cio-wiki.org/wiki/Congruence_Model. Accessed 22 May 2025.

6. “THE STAR MODEL™”. JAY R. GALBRAITH, https://jaygalbraith.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/StarModel.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2025.

7. “The Front And Back Model: How Does It Work.” Galbraith Management Consultants, https://jaygalbraith.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/FrontBackHowitWorks.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2025.

8. “Designing Dynamic Organizations: A Hands-on Guide for Leaders at All Levels.” Jay Galbraith, Diane Downey, and Amy Kates, https://www.amazon.com/Designing-Dynamic-Organizations-Hands-Leaders/dp/0814471196. Accessed 19 May 2025.

9. “New Management Job: The Integrator”. Paul R. Lawrence and Jay W. Lorsch (HBR), https://hbr.org/1967/11/new-management-job-the-integrator. Accessed 21 May 2025.

10. “Making Matrix Organizations Actually Work.” Herman Vantrappen and Frederic Wirtz (HBR), https://hbr.org/2016/03/making-matrix-organizations-actually-work. Accessed 21 May 2025.

11. “Balanced Scorecard”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/balanced-scorecard/. Accessed 21 May 2025.

12. “Value Statement: All You Need to Know”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/value-statement/. Accessed 21 May 2025.

13. “Designing Your Organization: Using the STAR Model to Solve 5 Critical Design Challenges”. Amy Kates and Jay R. Galbraith, https://www.amazon.com/Designing-Your-Organization-Critical-Challenges/dp/0787994944. Accessed 23 May 2025.