First-mover advantage is among the few management concepts with such intuitive appeal that its validity is almost taken for granted. However, there has been a long-running debate in the industry about the value of being first to market.

While most executives firmly believe that early entry into a new industry or product category gives any firm an almost insuperable head start, an analysis by Harvard reveals that for every academic study proving that first-mover advantages exist, there is a study proving they do not[1].

Research by Golder and Tellis[2] found that first movers had a failure rate of 47% with an average market share of only 10%. In comparison, firms that were early market leaders, but not necessarily first movers, had much lower failure rates (8%) and larger average market shares (28%).

Companies spend considerable resources seeking to increase the odds of beating their competitors to market and often fret about the commercial disadvantage of being late. Each year, they pour hundreds of millions into advertising to grow fast while hoping to get these advantages as VCs across the globe look for the next big win in a first mover.

Almost every industry has enough examples of leaders who were not first movers: Google wasn’t the first search engine; Facebook wasn’t the first social media; Spotify wasn’t the first online music platform and Tesla wasn’t the first to develop EVs for the masses[3].

But there are equally good examples of first movers, such as Gillette in safety razors, Sony in personal stereos, and Netflix in video streaming who have enjoyed long-term success by virtue of being first to the market.

What then decides if a firm can gain a successful first-mover advantage?

Should one venture into uncharted territory as a pioneer or opt for a well-trodden path to avoid the mistakes made by others? This article delves into the intricacies of this strategic decision.

First mover advantage: Origin, definition, and types

The term first-mover advantage was popularized by Marvin Lieberman and David Montgomery in their 1988 paper titled “First Movers Advantages”[4] which won the 1996 prize from the Strategic Management Society.

Subsequently, the authors backed off from most of their claims in a follow-up paper in 1998, First Movers (Dis)Advantages[5], but the term refused to die.

A first-mover advantage can be defined as a firm’s ability to be better off than its competitors as a result of being first to market in a new product category.

Although no advantage lasts forever, it is useful to distinguish between durable first-mover advantages, which improve a firm’s market share or profitability over a long period, and those that are short-lived.

Firms that succeed in building durable first-mover advantages tend to dominate their product categories for many years starting with a market’s infancy to its maturity. For example, Coca-Cola in soft drinks.

However even when a company cannot build a durable first-mover advantage, the benefits could still be justified. Whether the end comes suddenly or slowly, profits in a short-lived first entry may still be worthwhile to make it a strategic objective.

Netscape[6], for example, was the first to market an Internet browser that briefly produced enormous gains for its shareholders before it was killed by Microsoft’s predatory pricing.

Ways to create a first mover advantage

A first-mover advantage can be created in three main ways:

- Gaining a technological edge over competitors

- Limiting later arrivals’ access to scarce assets

- Building an early base of customers who then find it inconvenient or costly to switch

Gaining a technological edge

Firms that build first-mover advantages using technology edge stay ahead of the competition by out-innovating anyone else entering the market. Depending on the kind of technology, pioneers use patents and other legal remedies to block competition and maintain exclusivity.

For example, pharma companies invest billions of dollars into drug development which can take years or even decades – J&J’s psoriasis treatment drug, Stelara, introduced in 2009, has remained its top-selling drug since 2019 with sales reaching $9.7 billion in 2022[7].

Depending on the product, maintaining a technological edge can also give the first-mover a learning curve advantage which can translate into market dominance.

For example, Taiwan produces over 90% of the world’s most advanced chips and most are manufactured by a single company – Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC)[8].

TSMC was the world’s first pure-play foundry business model and has long been the leading company in its field[9]. Today, its fabrication facilities are so ahead of rivals that experts believe it’s impossible to replicate the complex technology and associated supply chain elsewhere.

Technology edge is suited to industries where insights are not obvious and can be kept secret. While patents and legal safeguards are effective in pharma, in most industries, they offer weak protection and are easy to ‘invent around’.

Limiting access to scarce resource

A first mover could potentially gain an advantage by limiting access to scarce assets like natural resources, shelf space or usage rights.

In the telecommunications industry, for example, many countries use spectrum auctions, a process whereby the government uses an auction system to sell the rights to transmit signals over specific bands of the electromagnetic spectrum. Firms that outbid other players gain exclusive rights to operate over defined sectors, thereby limiting entry of other players[10].

While firms do gain a first-mover advantage by limiting access to scarce resources, sustaining those advantages requires a relentless focus on technological innovation and customer experience.

Developing a loyal customer base

Sometimes, switching costs can create a durable first-mover advantage. Once customers are accustomed to a particular brand, the cognitive effort required to understand the benefits of an alternate brand is so high that most customers never make a switch.

Even though followers may have a better product, they need to put significantly more capital and effort into marketing and convincing customers to change their preferences.

A first mover can also lock in customers with loyalty programs in B2C or use long-term contracts in B2B.

Gillette’s ‘Razor & Blade Strategy’ is another effective way of retaining early customers. By selling good quality razors for cheap, Gillet locks its customers early on while earning a premium on blades[11].

There are enough examples of firms using switching costs to deter competition. However, today’s rapidly evolving technology landscape and shifting consumer preferences make it increasingly hard for first-mover firms to lock in customers.

Factors that influence first mover advantage

While internal factors such as the strategy through which a firm chooses to gain first-mover advantage, its resources and timing are important, a closer look at first-mover firms reveals the presence of other external factors which appear to be even more critical.

For example, one could argue that Sony’s long-term success with Walkman[12] as a first-mover could be attributed to its technological edge coupled with a strong brand name, substantial financial resources, and excellent marketing skills, but Sony couldn’t replicate this success in the VCR market.

Likewise, Xerox Corporation, which in 1964 introduced (and patented) the first commercial version of the modern fax machine soon lost the market to Japanese firms despite its great brand name, deep pockets, and many valuable skills[13].

A Harvard study based on an examination of literature and analysis of over 30 cases identified two critical factors that powerfully influence a first mover’s fate: the pace of technological evolution, and the pace of market expansion[1].

Unfortunately, these two background factors are external and typically beyond the control of any single firm.

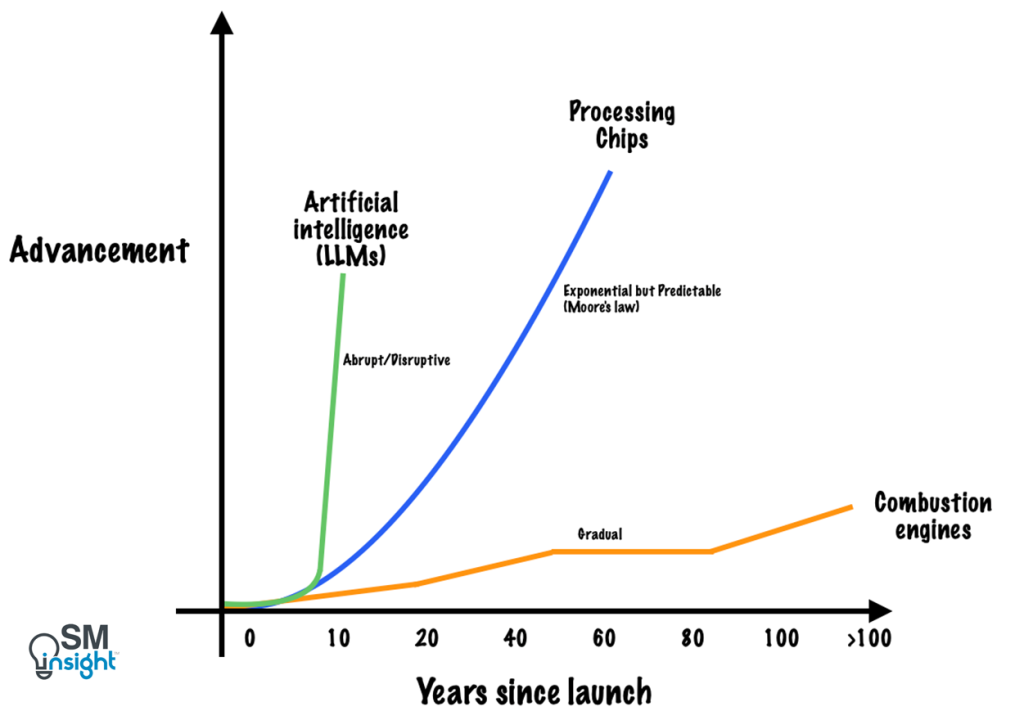

The pace of technological evolution

Depending on the kind of product or the industry, the pace at which technology evolves can vastly vary.

For example, in the 18th century, steam engines became the predominant source of propulsion following James Watt’s efficiency improvements in 1765[14]. It wasn’t until the late 19th century, nearly a hundred years later, that internal combustion (IC) engines gradually started replacing them. It took another century to get to the point where EVs are beginning to be seen as a viable alternative.

Despite over 150 years of evolution, the real-world efficiency of heat engines (collective term for steam as well as IC engines) remains below 40% due to thermodynamic constraints.

Compare that with the chip industry where a modern-day iPhone processor is vastly more powerful (over 5000 times!) than the supercomputer used by the US Department of Defense and Energy for nuclear weapons research and oceanographic development in 1985[15].

While the pace is one of the important factors that decide a first-mover advantage, predicting the trajectory followed by a technological improvement can also play a decisive role. For example, the advancement in processing chips, though rapid, was predicted by Moore’s law[16]. Firms largely knew what to expect.

However, the same cannot be said about Artificial Intelligence (AI) in general and Large Language Models (LLMs) in particular which have made groundbreaking advances in recent years and can generate human-like responses[17].

The faster or more disruptive the evolution of technology, the greater the challenge for any one company to control it. Even firms with deep pockets and large R&D budgets can find themselves outpaced by new entrants.

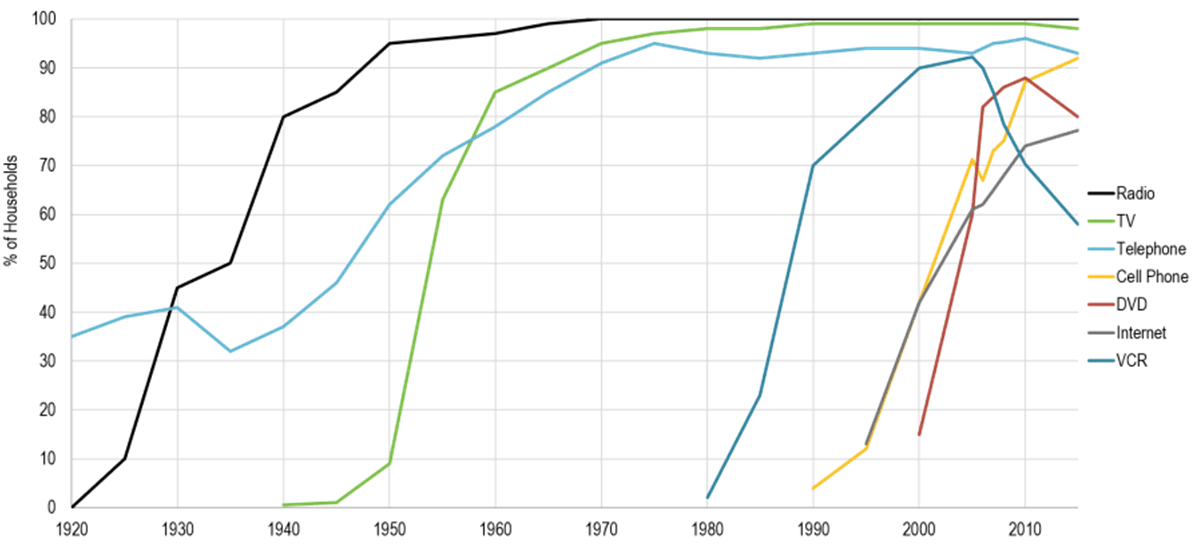

The pace of market expansion

The pace of market expansion can also vary widely but typically follows an “S” curve moving from an early phase of adoption to a fast penetration and ending with a slowdown as the market saturates and technology matures.

The chart below shows the adoption of various consumer electronics technologies in the US since the 1920s:

Some markets can also see a phase of obsolescence where the technology is replaced by a more efficient replacement.

For example, the market for VCRs died quickly as the standard was officially abandoned and replaced by the DVD, which then was replaced by video streaming.

In general, the greater a departure from existing products or categories, the more uncertain the pace of the market’s growth and its eventual shape will be.

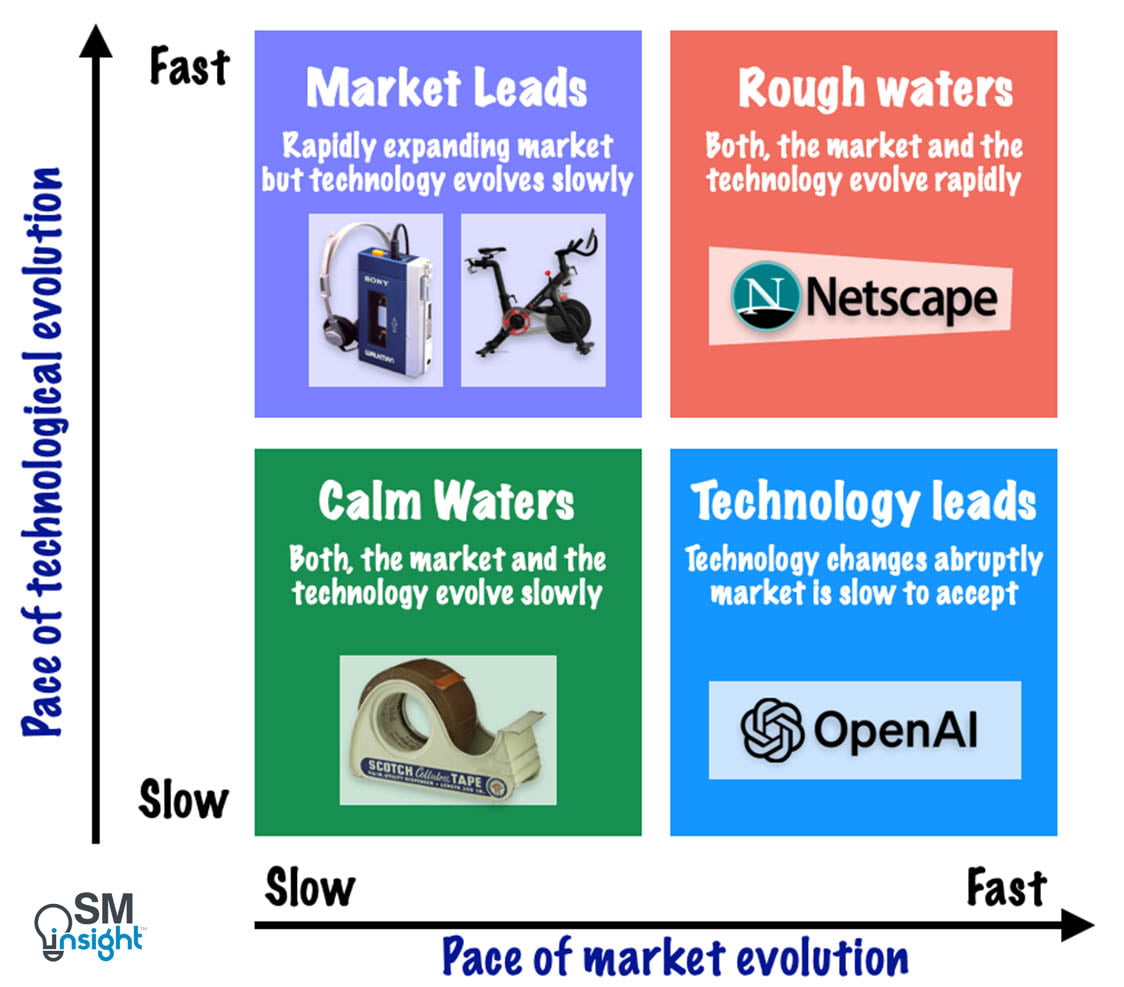

Converting First-Mover to Advantage

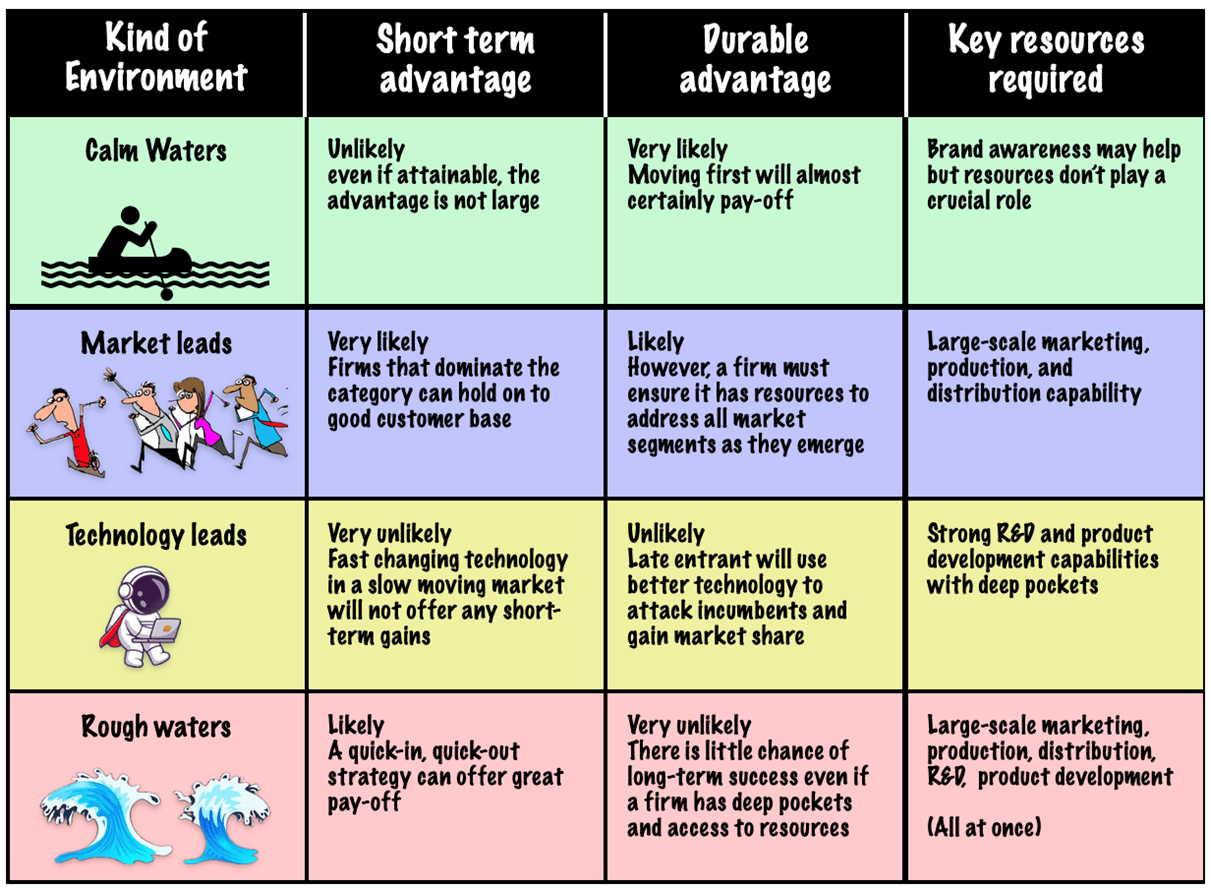

A firm’s ability to capitalize on its first-mover advantage is decided by the combined effects of market and technological change. Four possibilities arise, each of which requires a different approach:

When both, technology and the market evolve gradually

Referred to as “Calm Waters”, this environment is characterized by a gradual pace of technology and market evolution. It is an ideal condition for a first-mover to create a dominant long-lasting position.

While a slow pace of market growth favors the first mover by giving time to cultivate and satisfy new market segments, a gradual pace of change in technology makes it hard for later entrants to differentiate their products from the already-established first entrant.

Even if competitors discover some means of doing so, the improvements are generally not rapid or drastic enough to prevent the first mover from integrating them (in time) into their own product offerings.

Resource requirements, such as skills, capabilities, and assets that an organization develops over time are less critical than they would be in other technology-and-market environments.

A first mover in calm waters must focus on product development, production, and marketing and most importantly, focus on building a brand.

Physical assets, such as strategic locations, financial resources and skills are always desirable, but in calm waters, a first entrant lacking those advantages still stands a chance and the means to defend its product against later competitors.

Scotch tape, which debuted in the 1930s right at the start of the Great Depression is a classic example of a product success in clam waters. 3M’s Richard Drew invented the tape and hoped the product would be useful in industrial settings.

Instead, it was taken up by ordinary people who were looking to repair items which in more affluent times might have been discarded. Scotch tape found use in everything from mending clothing to capping milk bottles and even repairing cracked eggs.

The gradual growth of Scotch Tape’s appeal gave 3M time to organize production and distribution while a modest technological change helped stay up-to-date and prevent later entrants from both introducing superior versions and “inventing around” 3M’s patent.

No major changes were made to the Scotch tape for the next 30 years until 3M released the almost-invisible Magic Transparent Tape in 1961[20].

When market leads and technology follows

This kind of environment is characterized by a rapidly expanding market and comparatively slower technological advancements. As the market expansion can be abrupt, unless a first-mover firm has vastly superior resources at its disposal, benefits are usually short-lived.

For example, using mature technologies readily available at the time, Sony introduced its portable music player – the Walkman in 1979. While the basic technical design of portable players remained unchanged, its market grew abruptly with sales reaching close to 40 million units in less than ten years.

Despite this enormous expansion rate and potential size, Sony’s market share was close to 48% even ten years after the Walkman’s launch. Sony could achieve this success because of its enormous resource pool that included superior design skills, marketing muscle, and a strong brand.

It can be hard for a firm with few skills and resources to achieve long-term benefits like Sony’s Walkman in a rapidly growing market, but they can still pursue short-term opportunities.

For example, driven by the pandemic, when the indoor fitness industry exploded, Peloton Interactive, a pioneer in high-end indoor cycling benefitted immensely. Despite weak distribution channels and poor customer service, Peloton managed to double its sales to $1.82 billion in 2020 and then again to over $4 billion in 2021.

Despite the end of pandemic-imposed restrictions, the indoor fitness industry continued to grow as consumers realized the importance of health and wellness. Peloton’s advantage however was short-lived as competitors soon introduced better products and substitutes for indoor workouts[21].

When technology leads and the market follows

In this environment, technology changes abruptly, but the market is slow to accept the new product category. Consequently, early entrants face years of flat sales and operating losses.

A short-lived first-mover advantage is very unlikely in this environment as the rapid advancement in technology constantly attracts new competitors who believe their improvements will draw customers away from the incumbents. This also neutralizes the chance of gaining a durable advantage for both early as well as late entrants.

This hostile environment created by rapidly evolving technology is suited only to firms with very deep pockets and superior R&D capabilities. They must remain at the technological forefront and endure a considerable delay until eventually, the pace of technological change slows, or a new technology stabilizes to become the standard.

Once this happens, the market takes off and durable first-mover advantages begin to show.

AI today is going through this phase where its applications are rapidly expanding but a business case seems elusive. According to McKinsey and Company, only about 20% of AI-aware companies are currently using one or more AI technologies in a core business process or at scale[24].

While AI applications have rapidly evolved, the market for them hasn’t. For example, an airline could use facial recognition and other biometric scanning technology to streamline aircraft boarding, but the value of doing so may not (yet) justify the complexities around privacy and personal identification.

Similarly, in some areas of healthcare, AI can already diagnose problems with superhuman precision and even automate medical procedures[25]. However, adopting such technologies at scale will require addressing regulations and policies which will take time.

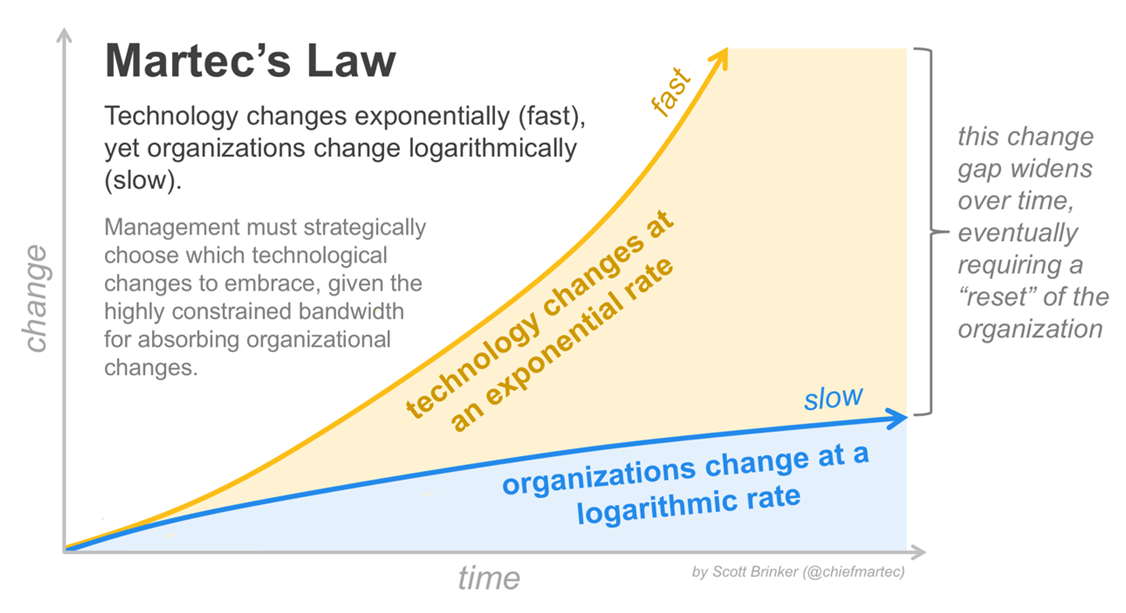

Firms that operate in this environment also face the institutional resistance of adapting to rapidly changing technology. Scott Brinker called this Martec’s Law[26], according to which, technology changes exponentially (fast) yet organizations change logarithmically (slow).

There are only so many changes in people, processes, and technology that a firm can productively absorb at once which can create a widening gap that eventually requires an organisational reset.

When both, technology and the market evolve rapidly

Referred to as “Rough Waters”, this is a hostile environment where securing a lasting first-mover advantage is exceptionally rare and first-movers often encounter more obstacles compared to followers.

When a product’s underlying technology changes very rapidly, it quickly becomes obsolete and is substituted by versions from new entrants. As new entrants aren’t burdened with maintaining and servicing older product lines, they can innovate without fear of cannibalizing prior investments.

A fast-growing market also adds to a first mover’s challenges by opening attractive new competitive spaces for later entrants to exploit. Incumbents tend to be at a disadvantage since they often lack the production capacity or marketing reach to serve a rapidly expanding customer base.

While long-term benefits are unlikely, most first movers in rough waters may still be able to achieve worthwhile short-term gains, provided their exit is well-timed.

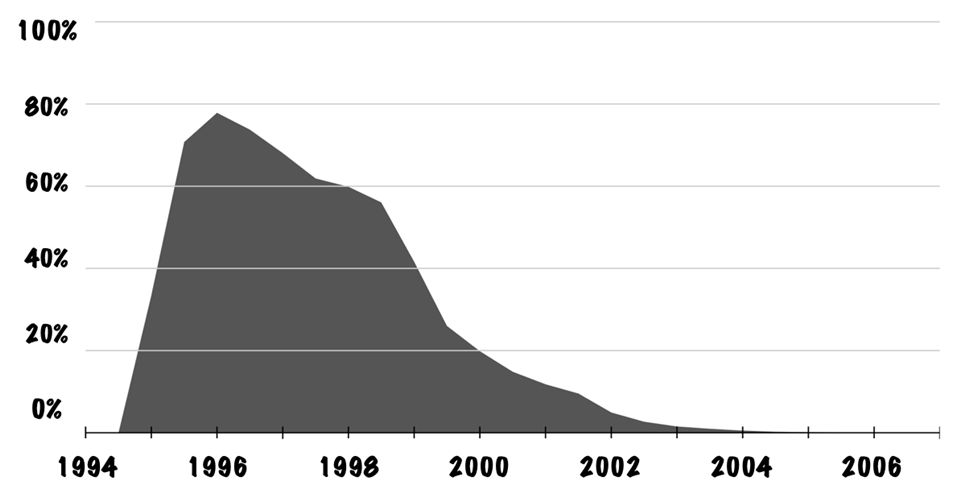

For example, in the 1990s, when internet technologies burgeoned, web browsers demonstrated a typical “rough water” environment. Netscape was the first company to capitalize on the growing demand for web browsers.

Its first web browser Mosaic Netscape 0.9 (later renamed Netscape Navigator) launched in October 1994 and captured a 75% browser market share in just four months. Netscape translated this dominance into an extremely successful IPO in August 1995[27].

The frantic market growth pace later attracted formidable players like Microsoft who found plenty of space to grow. Within the next five years, Microsoft killed Netscape’s browser dominance by providing its own browser free of cost to Windows users.

By 2003, Netscape Navigator’s market share was too insignificant to mention. But before the browser was destroyed, Netscape managed to get acquired by AOL in a $10 billion deal in 1999[28].

Only firms with mighty resources, far superior to those of competitors, can hope to achieve longer-term first-mover advantages when both technology and markets are moving rapidly.

But possession of substantial resources is no guarantee of winning.

For example, when IBM introduced the hard drive in the late 1950s, it was the largest computer maker in the world. Since then, a sequence of fast-growing markets for computers and laptops generated relentless demand for better hard drives.

Despite a superb brand name and plenty of resources, IBM could not stay atop the hard-drive industry for long. It eventually sold the majority stakes of its hard disk drive (HDD) business to Hitachi in 2002[30].

Should a firm be a first mover?

Most markets are characterized by constant emergence of new product categories. Often the decision that firms struggle with is not whether to enter but when.

The four environments discussed thus far require very different sets of assets and capabilities for firms to win. Stepping into an environment with the wrong set of resources can give firms a rough time.

The below figure breaks down the kind of advantage a first-mover firm can hope to gain along with the needed resources to maximize the odds of success:

(Data Source: The Half-Truth of First-Mover Advantage, Harvard Business Review[1])

Contrary to popular belief, a first-mover advantage is not guaranteed. To make real gains, firms must analyze their environment, evaluate the depth of their resources, and set realistic expectations regarding the type and timing of any potential first-mover advantage – whether it’s short-term, lasting, immediate, or delayed, or if it is attainable at all.

Sources

1. “The Half-Truth of First-Mover Advantage”. Fernando F. Suarez and Gianvito Lanzolla (Harvard Business Review), https://hbr.org/2005/04/the-half-truth-of-first-mover-advantage. Accessed 01 Apr 2024.

2. “Pioneer Advantage: Marketing Logic or Marketing Legend?”. Peter N. Golder and Gerard J. Tellis, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228178742_Pioneer_Advantage_Marketing_Logic_or_Marketing_Legend. Accessed 03 Apr 2024.

3. “History of the electric car: from the first EV to the present day”. Auto Express, https://www.autoexpress.co.uk/car-news/electric-cars/101002/history-of-the-ev-from-the-first-electric-car-to-the-present-day. Accessed 03 Apr 2024.

4. “First-mover advantages”. Marvin B. Lieberman and David B. Montgomery, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/smj.4250090706. Accessed 03 Apr 2024.

5. “FIRST-MOVER (DIS)ADVANTAGES: RETROSPECTIVE AND LINK WITH THE RESOURCE-BASED VIEW”. Marvin B. Lieberman, David B. Montgomery, https://www.anderson.ucla.edu/faculty_pages/marvin.lieberman/publications/FMA2-SMH1998.pdf. Accessed 03 Apr 2024.

6. “Netscape”. Netscape, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Netscape. Accessed 06 Apr 2024.

7. “Analysis: Stelara patent deal puts J&J back on path to $57 billion 2025 revenue forecast”. Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/stelara-patent-deal-puts-jj-back-path-57-bln-2025-revenue-forecast-2023-06-05/. Accessed 03 Apr 2024.

8. “No industry matters more to Taiwan than chipmaking”. The Economist, https://www.economist.com/special-report/2023/03/06/taiwans-dominance-of-the-chip-industry-makes-it-more-important. Accessed 03 Apr 2024.

9. “About TSMC”. TSMC, https://investor.tsmc.com/static/annualReports/2022/english/index.html. Accessed 03 Apr 2024.

10. “First mover advantages in mobile telecommunications: Evidence from OECD countries”. Muck Johannes and Heimeshoff Ulrich, https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/65677/1/728888483.pdf. Accessed 06 Apr 2024.

11. “Gillette Marketing Strategy of product innovation”. The Strategy Story, https://thestrategystory.com/2021/08/02/gillette-marketing-strategy-innovation/. Accessed 03 Apr 2024.

12. “The history of the Walkman: 35 years of iconic music players”. The Verge, https://www.theverge.com/2014/7/1/5861062/sony-walkman-at-35. Accessed 06 Apr 2024.

13. “The History of Fax (from 1843 to Present Day)”. Faxauthority, https://faxauthority.com/fax-history/#RiseOfFax. Accessed 03 Apr 2024.

14. “Watt steam engine”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watt_steam_engine. Accessed 07 Apr 2024.

15. “Fast-forward — comparing a 1980s supercomputer to a modern smartphone”. Adobe, https://blog.adobe.com/en/publish/2022/11/08/fast-forward-comparing-1980s-supercomputer-to-modern-smartphone. Accessed 04 Apr 2024.

16. “Moore’s Law”. Intel, https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/newsroom/resources/moores-law.html. Accessed 06 Apr 2024.

17. “The brief history of artificial intelligence: The world has changed fast – what might be next?”. Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/brief-history-of-ai. Accessed 06 Apr 2024.

18. “US Household Penetration of Telecommunications, 1920-2015”. Dept. of Global Studies & Geography, Hofstra University, New York, USA., https://transportgeography.org/contents/chapter1/the-setting-of-global-transportation-systems/household-telecommunications-united-states/. Accessed 04 Apr 2024.

19. “Almanac: Scotch tape”. CBS News, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/almanac-scotch-tape/. Accessed 07 Apr 2024.

20. “Scotch Transparent Tape”. American Chemical Society, https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/scotchtape.html. Accessed 06 Apr 2024.

21. “What Is Happening With Peloton? And Other Pandemic Lessons”. Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/lizelting/2022/01/27/what-the-heck-is-happening-with-peloton-and-other-pandemic-lessons/. Accessed 06 Apr 2024.

22. “Product & Technology Milestones”. Sony, https://www.sony.com/en/SonyInfo/CorporateInfo/History/sonyhistory-e.html. Accessed 07 Apr 2024.

23. “Peloton Bike”. Peloton, https://www.onepeloton.com/shop/bike/bike-package. Accessed 07 Apr 2024.

24. “Notes from the AI frontier: Applications and value of deep learning”. McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/artificial-intelligence/notes-from-the-ai-frontier-applications-and-value-of-deep-learning. Accessed 05 Apr 2024.

25. “AI Accurately Identifies Normal and Abnormal Chest X-Rays”. Radiological Society of North America, https://www.rsna.org/news/2023/march/ai-identifies-normal-abnormal-xrays. Accessed 05 Apr 2024.

26. “Martec’s Law: the greatest management challenge of the 21st century”. Scott Brinker, https://chiefmartec.com/2016/11/martecs-law-great-management-challenge-21st-century/. Accessed 05 Apr 2024.

27. “Netscape: The IPO that launched an era”. Market Watch, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/netscape-ipo-ignited-the-boom-taught-some-hard-lessons-20058518550. Accessed 07 Apr 2024.

28. “AOL Says Deal to Acquire Netscape Has Been Completed”. The Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB921707787528132061. Accessed 07 Apr 2024.

29. “Netscape Navigator”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Netscape_Navigator. Accessed 05 Apr 2024.

30. “Hitachi buys IBM’s hard drive business for $2B”. Computer World, https://www.computerworld.com/article/2792937/hitachi-buys-ibm-s-hard-drive-business-for–2b.html. Accessed 05 Apr 2024.