Technologists assume good innovations will automatically sell themselves, that the obvious benefits of a new idea will be widely realized, and that the innovation will spread.

But this is rarely the case.

During the seafaring age between 1500 and 1800, scurvy killed about two million sailors. The cure was simple: lime juice. Although the fruit’s beneficial properties became known in the early 16th century, it took almost 200 years for the Royal Navy to begin issuing lemon juice to sailors [1].

Contrast that with the Fidget spinner, a stress-reliever toy that became a worldwide phenomenon in under six months despite little scientific evidence to prove its benefits [2].

What explains this varying rate of innovation spread?

In 1962, Everett M. Rogers sought to answer that question. Building on past research [3], Roger developed the Diffusion Of Innovations (DOI) Theory, a time-tested framework that explains why some products diffuse rapidly, some slowly, and some not at all.

Geoffrey A. Moore further modified DOI theory in his book “Crossing the Chasm” to explain the market dynamics of innovative new products and how gaps between different customer groups can lead to product failures [4].

What is diffusion?

Diffusion is the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time across society. It is a special type of communication in which messages concern new ideas.

Diffusion can also be viewed as the process by which an alteration occurs in the structure and function of a social system. This social change occurs when new ideas are invented, diffused, adopted, or rejected, leading to consequences.

Because new ideas bring change, diffusion involves some degree of uncertainty. Even when the benefits of new ideas are demonstrated, diffusion and adoption are not guaranteed.

Components of Diffusion

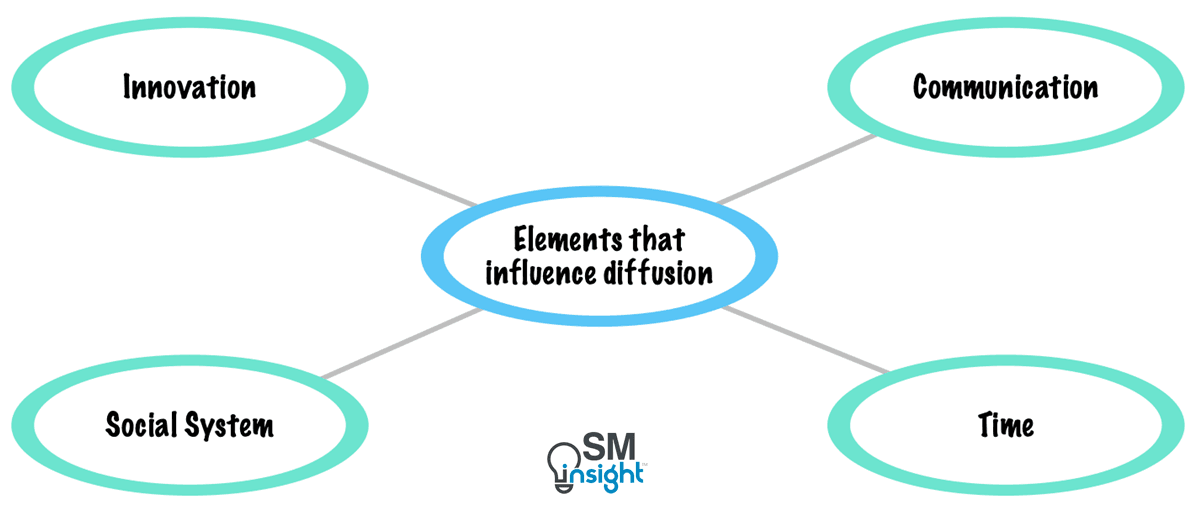

According to Rogers, there are four main elements that influence how an innovation is diffused:

1. Innovation

Innovation is an idea, practice, or object perceived as new by an individual. It does not matter whether it is “objectively” new, as measured by the time elapsed since its first use or discovery.

If an idea seems new to the individual, it is an innovation.

Newness also need not just involve new knowledge. An individual may have known about it for some time but not yet developed a favorable or unfavorable attitude toward it, nor have adopted or rejected it.

Thus, an innovation’s “Newness” can be expressed through knowledge, persuasion, or a decision to adopt it.

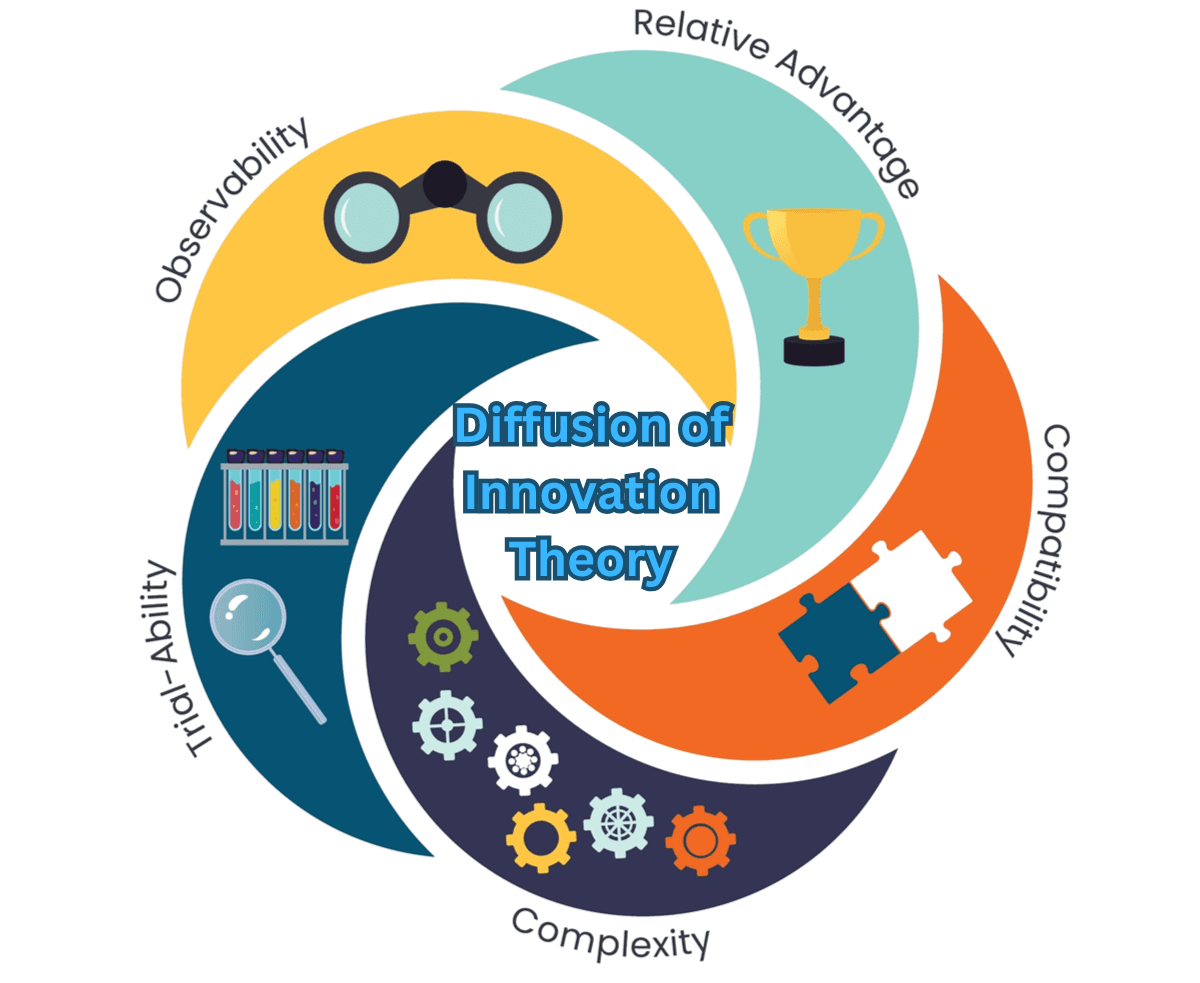

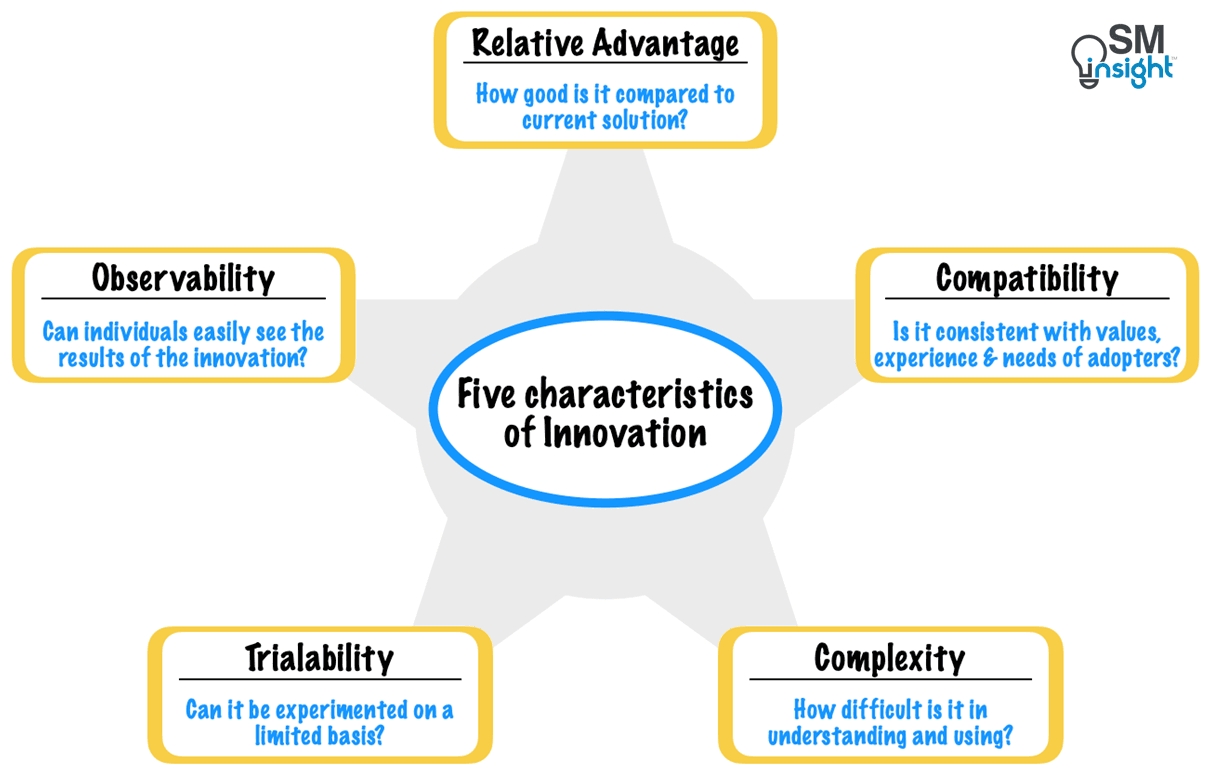

Every innovation has five main characteristics, as perceived by individuals, that help explain their varying rates of adoption:

- Relative advantage—the degree to which an innovation is perceived as better than the idea it supersedes. While this is generally measured in economic terms, social prestige, convenience, and satisfaction are also important factors.

How an individual perceives the innovation as advantageous matters more than its “objective” advantage. The greater the perception, the more rapid the adoption rate. - Compatibility—the degree to which an innovation is perceived as consistent with the existing values, past experiences, and needs of potential adopters. If an idea is incompatible with a social system’s values and norms, adoption will slow.

- Complexity—the degree to which an innovation is perceived as difficult to understand and use. Complicated innovations require the adopter to develop new skills and understanding; hence, they are adopted slowly.

The Dvorak keyboard, for example, is an efficient design compared to Qwerty but was never adapted due to the learning curve and changes required [5]. - Trialability—the degree to which an innovation may be experimented with on a limited basis. Trialable innovations represent less uncertainty to the individual considering it for adoption, as it is possible to learn by doing.

Additionally, ideas that can be tried on installment are generally adopted more quickly than innovations that are not divisible. - Observability—the easier it is for individuals to see the results of an innovation, the more likely they are to adopt it. Visibility stimulates peer discussion, prompting friends and neighbors to request information and evaluate the innovation.

Solar panels, for example, were initially adapted in neighborhood clusters with three or four early adopters in the same block [6].

In addition to the five characteristics above, innovations have another important property: they undergo change during diffusion as adopters customize them to fit their unique needs.

Innovations that individuals can re-invent or modify tend to diffuse more rapidly and are likely to be sustained.

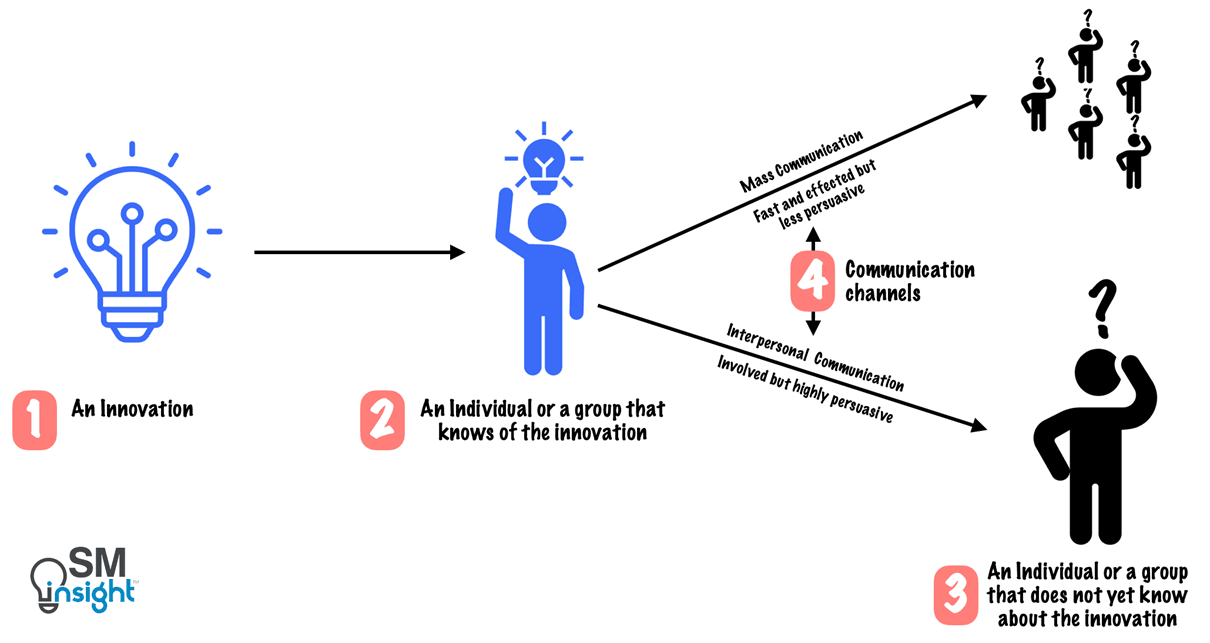

2. Communication channels

The essence of the diffusion process is the information exchange through which an individual communicates a new idea to one or several others. At its most elementary form, the process involves:

- An innovation

- An individual or a group that knows about innovation

- An individual or a group that doesn’t yet know about the innovation

- A communication channel connecting the two units

In this communication process, the relationship between two sides plays an important role in determining how the innovation will be received.

Mass media channels, for example, are rapid and efficient in informing many potential adopters and creating awareness, but they lack the persuasion of face-to-face interaction. Interpersonal channels are more effective in persuading individuals to accept new ideas.

Studies indicate that people are strongly influenced when they share something in common with the persuader who has already adopted an innovation rather than by scientific studies showing the innovation’s benefits.

This dependence on the experience of near peers suggests that diffusion is a very social process that involves interpersonal communication and relationships.

The nature of diffusion thus demands at least some similarity between participants in the communication process.

3. Time

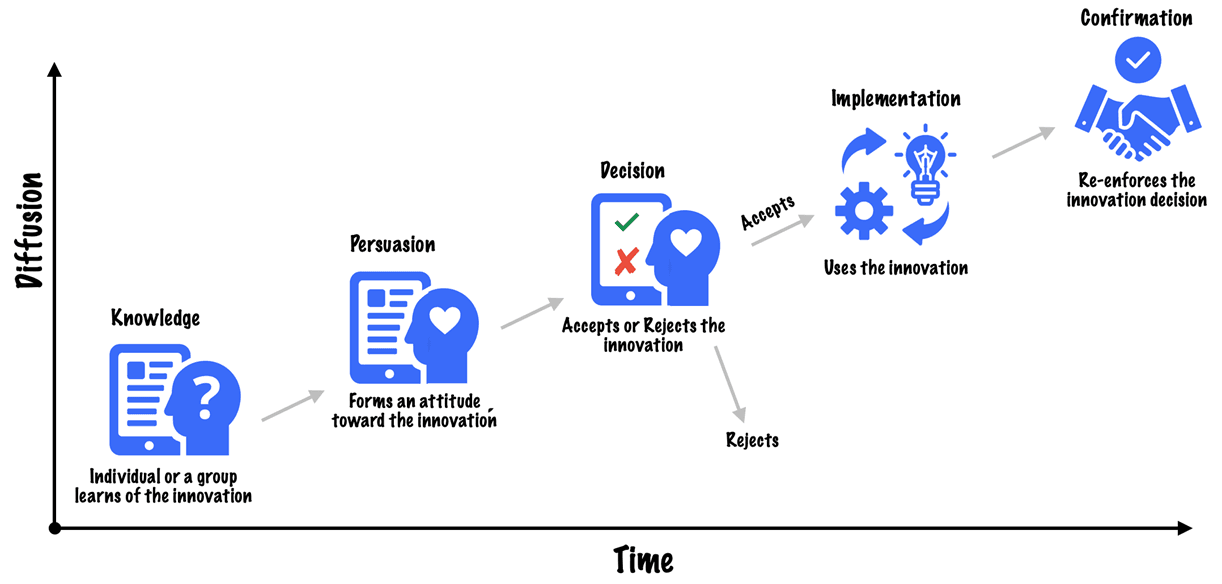

In DOI theory, time is an important element. The innovation-diffusion process usually occurs in a time-ordered sequence of five stages:

- Knowledge—is gained when an individual (or other decision-making unit) learns of the innovation’s existence and gains some understanding of how it functions.

- Persuasion—occurs when an individual forms a favorable or unfavorable attitude toward an innovation.

- Decision—occurs when an individual engages in activities that lead to a choice to adopt or reject the innovation.

- Implementation—occurs when an individual uses. Re-invention is also likely to occur at this stage.

- Confirmation—occurs when an individual reinforces an innovation–decision that has already been made. If exposed to conflicting messages about the innovation, an individual may reverse the previous decision.

This is an information-seeking and information-processing activity in which an individual obtains information to gradually decrease uncertainty about the innovation, leading to either adoption or rejection.

The time required to pass through the innovation-decision process can vary across individuals. Some require many years to adopt an innovation, while others move rapidly from knowledge to implementation.

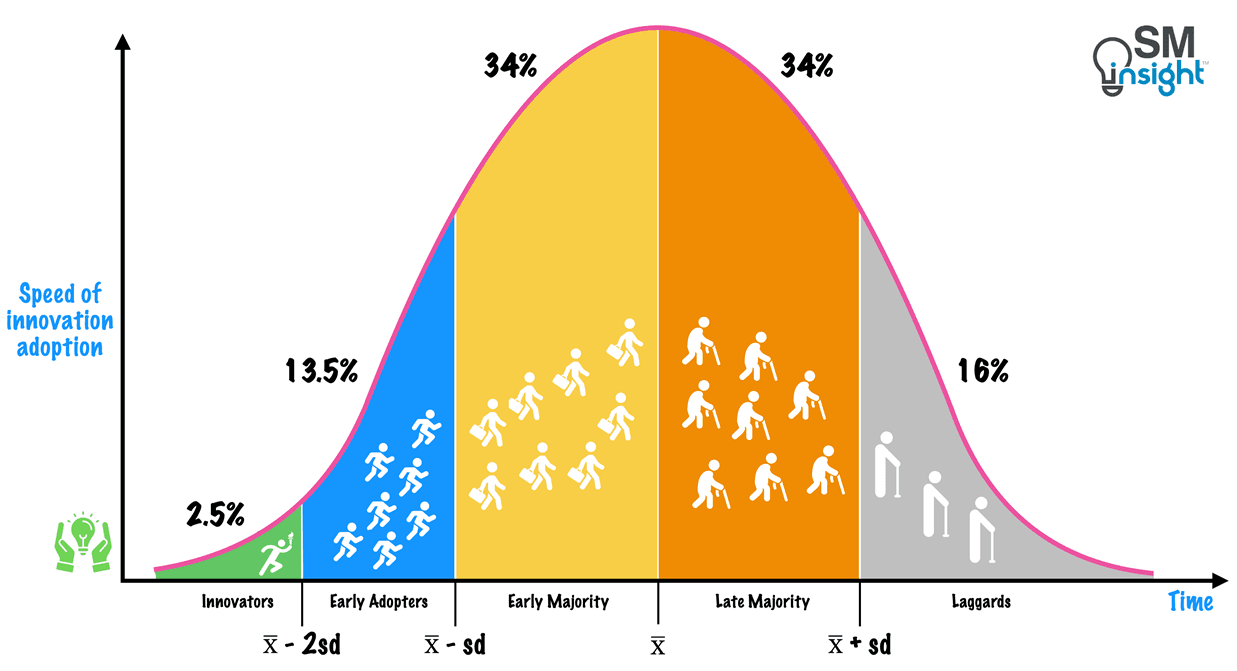

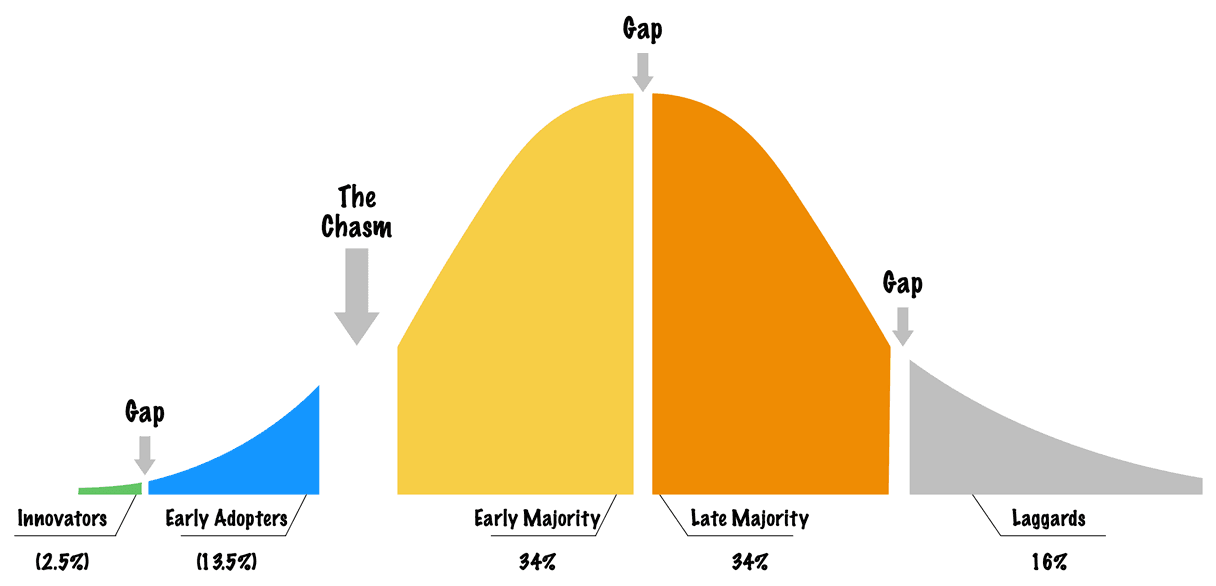

One of the ways the DOI theory explains this variation is by using adopter categories. It classifies the members of a social system into five categories based on their innovativeness (the degree to which they are relatively early in adopting new ideas).

When the speed of adoption is plotted against time, we get a bell curve with divisions roughly equivalent to standard deviations, as shown.

The early and late majority each fall within one standard deviation of the mean, the early adopters and the laggards within two, and the innovators are way out, about three standard deviations from the norm at the very onset of new technology.

Each of these five adopter categories shares a great deal of commonality:

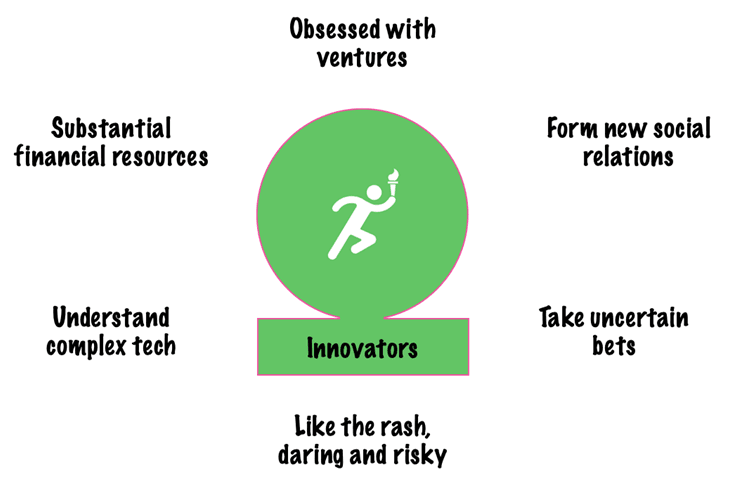

Innovators

About 2.5 % of the people are innovators. Theyare obsessed with ventures and desire the rash, the daring, and the risky. Their interest in new ideas drives them to form new social relationships.

Innovators need access to substantial financial resources to absorb possible losses from unprofitable innovations. They must understand complex technical knowledge, cope with high uncertainty, and be willing to accept occasional setbacks when new ideas fail.

Although innovators do not greatly influence the larger society, they play an important role in the diffusion process by importing innovation into society. They are the gatekeepers to the flow of new ideas into a system.

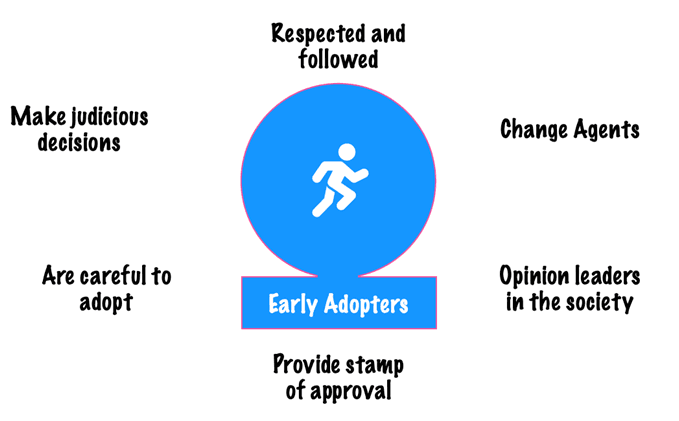

Early Adopters

Early adopters constitute about 13.5% of the population and are a more integrated part of the social system than innovators. They are the local missionaries who speed up the diffusion process.

They have the highest degree of opinion leadership in most systems, as potential adopters look to them for advice and information about innovations. Most people see early adopters as the “individuals to check with” before adapting an idea.

Because early adopters are not too far ahead of the average individual in innovativeness, they serve as role models for other members and help trigger the critical mass when they adopt an innovation.

Early adopters are respected by peers and embody successful, discrete use of new ideas. They know that they must make judicious decisions related to innovation and are careful about it.

Early adopters decrease uncertainty about a new idea by adopting it and then conveying a subjective evaluation of the innovation to near-peers through interpersonal networks. Their adoption puts a stamp of approval on a new idea.

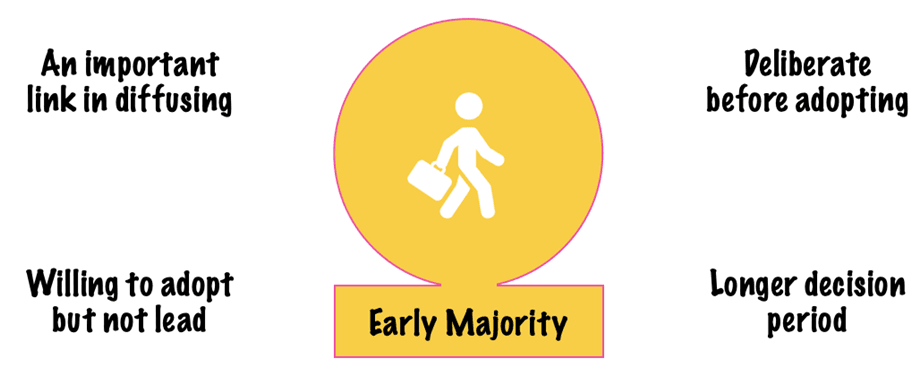

Early Majority

The early majority adopt new ideas just before average members do and constitute about 35% of the population. This is where most new products begin to turn profitable. This group frequently interacts with peers but seldom holds positions of opinion leadership.

Their unique position between the very early and the relatively late adopters makes them an important link in the diffusion process. They help connect society’s interpersonal networks.

They usually deliberate for some time before adopting a new idea and tend to have an innovation-decision period that is relatively longer than that of the innovators and the early adopters. They follow with a deliberate willingness to adopt innovations but seldom lead.

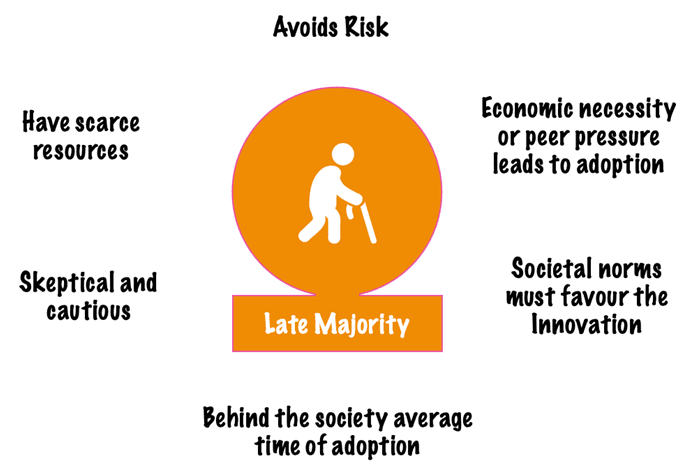

Late Majority

These adopt new ideas just after the average member of a system. Like the early majority, they comprise over a third of the population.

Adoption could be triggered by economic necessity or increasing peer pressures. The late majority approach innovations skeptically and cautiously, delaying them until most others in the system have already adopted them.

Societal norms must favor an innovation before the late majority is convinced to adopt it. Peer pressure, too, is a necessary element. Because this group has relatively scarce resources, uncertainty around a new idea must be eliminated before they feel it’s safe to adopt it.

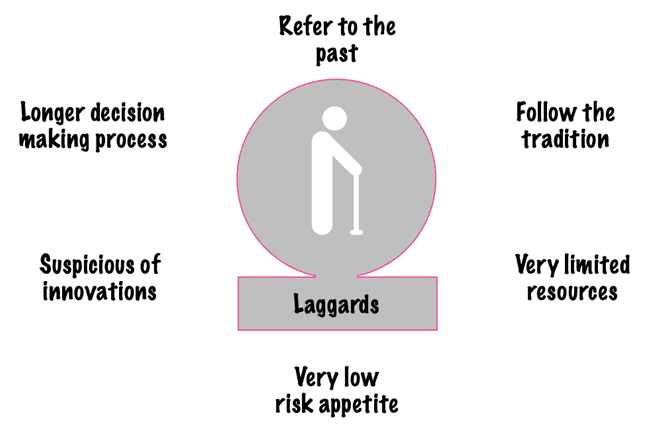

Laggards

Laggards are the last to adopt an innovation. Their point of reference is often the past, and their decisions are shaped by what has been done previously. They primarily interact with others who also share traditional values.

Laggard’s precarious economic position and limited resources mean they must be certain that a new idea will not fail before adopting it. They tend to be suspicious of innovations and follow a lengthy decision-making process.

About 16% of members of the social system are laggards.

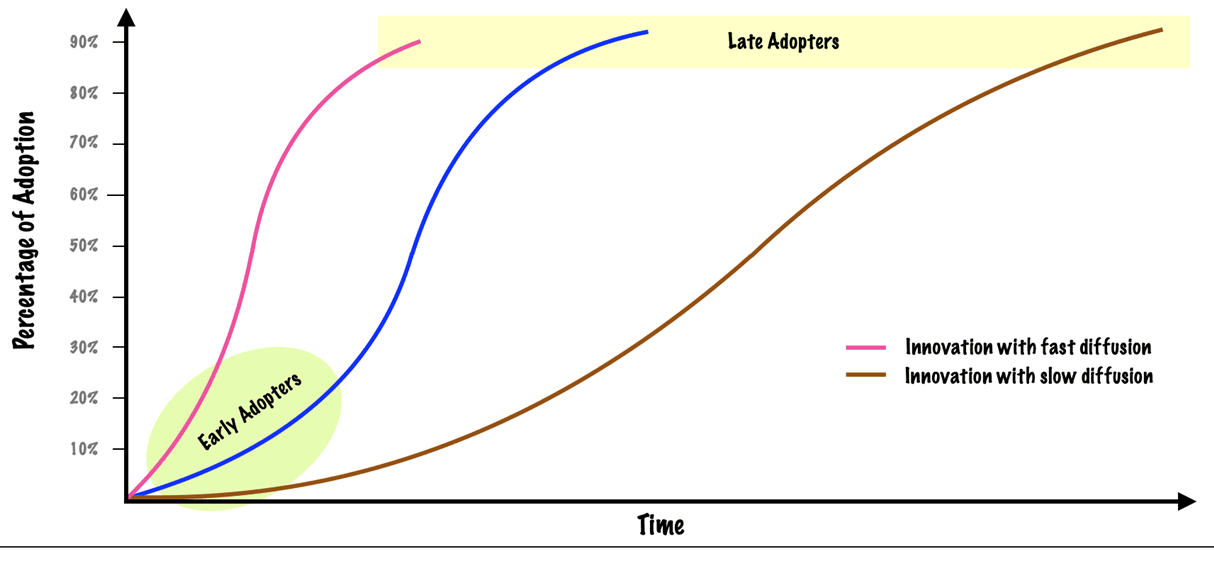

The S-Curve of Adoption

When plotted against time, the diffusion process follows an S-curve. At first, only a few individuals adopt an innovation. With the passage of time, as more individuals adopt, the curve begins to climb.

Eventually, the trajectory of the adoption rate tapers off as few individuals remain yet to adopt, and the S-curve eventually reaches its asymptote, ending the diffusion process.

The slope of the S-curve can vary. Ideas that diffuse rapidly have a steeper slope, while those that diffuse slowly form a gradual or lazy S-curve.

4. The Social System

A social system is a set of interrelated units engaged in joint problem-solving to accomplish a common goal. Its members could be individuals, informal groups, or organizations cooperating to solve a common problem.

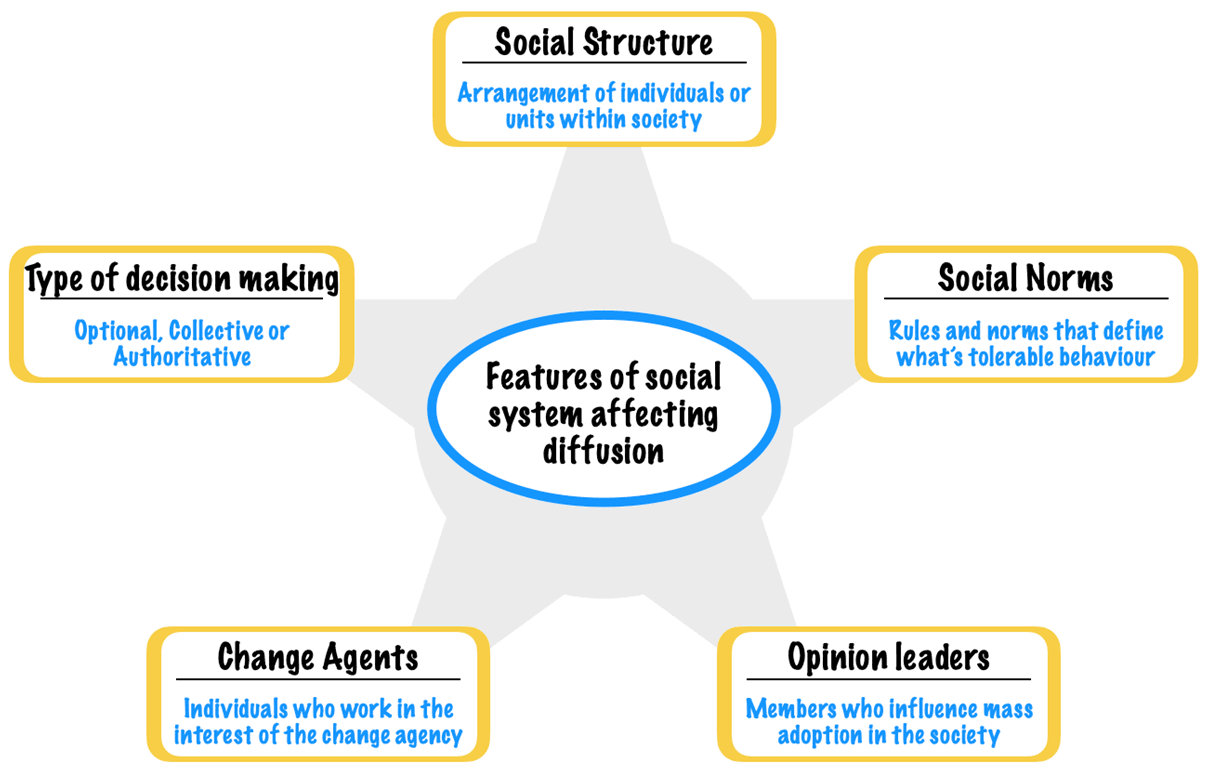

Several features of the social system can affect diffusion:

Social Structure

Units within a social system have social structures, a patterned arrangement of individuals, that regulate and stabilize human behavior.

For example, a well-developed structure, such as a government organization, consists of hierarchical positions where individuals can issue orders and expect them to be followed. Likewise, informal structures exist in other places, consisting of interpersonal networks that define who interacts with whom and under what circumstances.

Such structures can facilitate or impede diffusion.

Social Norms

Norms are established behavior patterns that define tolerable behavior and serve as a societal guide or standard.

Social norms can either facilitate or hinder the adoption of innovation. They can have an impact at the national, religious, organizational, or local community level, such as a village.

For example, during the pandemic, some countries could easily implement the wearing of masks, yet others found it difficult to adapt despite known health risks [7].

Opinion leaders

Every social system has members who function as opinion leaders. They provide information and advice about innovations to many others in the system, hold considerable influence, and shape attitudes.

Opinion leadership is earned and maintained through technical competence, social accessibility, and conformity to the system’s norms rather than solely by an individual’s formal position or status.

Compared to followers, opinion leaders are generally more exposed to all forms of external communication, have a higher socioeconomic status, and are innovative. They are at the center of interpersonal communication networks.

Elon Musk, for example, is an innovator and opinion leader known for his influence in the tech and space industries. His advocacy for electric vehicles and renewable energy has led to the accelerated diffusion of these technologies.

Because opinion leaders serve as models for the innovative behavior of their followers, when they are more innovative, society is more open to diffusion.

Change Agents

Change agents are individuals who influence society members’ innovation decisions in a direction deemed desirable by a change agency. While they usually seek to accelerate adoption, they may also attempt to slow down the diffusion of undesirable innovations.

These are usually qualified professionals with technical knowledge and the social status that comes with it. They often use opinion leaders as their lieutenants in diffusion activities.

Type Of Societal Decision Making

Innovations can be adopted or rejected by individuals or by the society. Primarily, three kinds of decision-making exist that decide the pace of diffusion:

- Optional innovation decisions—these are innovation adoption decisions made by individuals and are independent of the decisions made by others in society.

While societal norms and structures may influence such decisions, the distinctive aspect of optional innovation decisions is that the individual is the main decision-making unit.

For example, whether or not to buy an electric car is an optional decision left to individuals. - Collective innovation decisions—these are choices made by consensus among societal members. Individuals must conform to the system’s decision once it is made.

For example, a company may adopt remote work after consensus among employees; a town may collectively decide to ban single-use plastics after consulting with residents. - Authority innovation decisions—these are choices made by relatively few individuals in a system who possess power, status, or technical expertise.

Individuals have little or no influence on the authority innovation decision. Once made, they must simply implement. Airbags in cars, for example, are not optional but mandated by law.

Authoritative innovation decisions, quite obviously, have the fastest rate of adoption.

Impact of Innovation Adoption Curve on Marketing

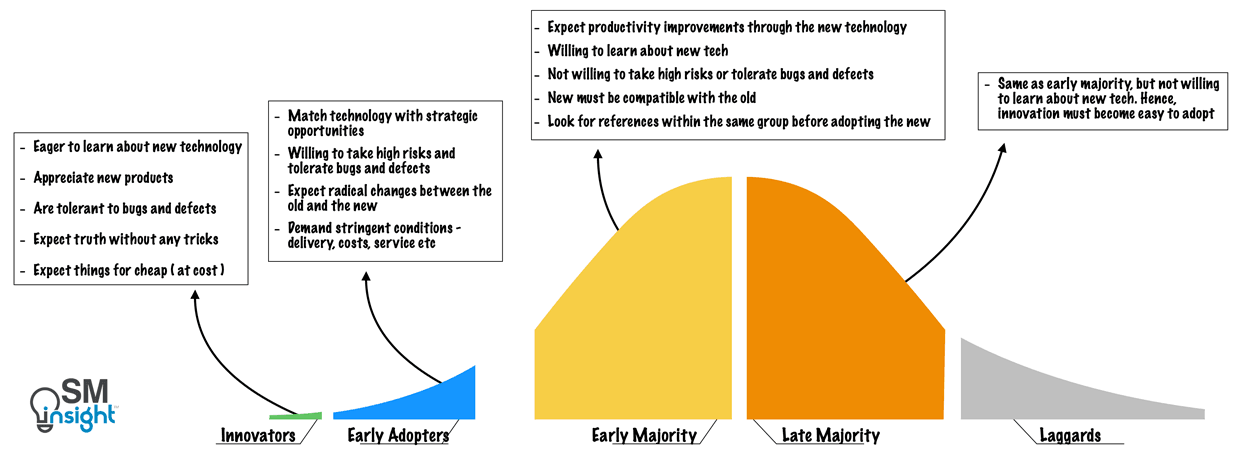

Each adopter category in the adoption curve represents a unique psychographic profile—a combination of psychology and demographics that makes its marketing responses different from those of the other groups.

Understanding each profile and its relationship to neighbors provides a critical foundation for effective marketing.

What Different Adopter Groups Care About

What Innovators Care About

Innovators aggressively pursue new products, services, and technologies. They sometimes seek them out even before a formal marketing program has been launched. New tech is a central interest in their life, regardless of its function. They are intrigued by fundamental advancements and often purchase simply to explore the new.

There are not very many innovators in any given market segment but winning them over at the outset of a marketing campaign is important for firms as their endorsement reassures others in the marketplace that the product could, in fact, work.

What Early Adopters Care About

Like innovators, early adopters buy into new product concepts very early in their life cycle. They find it easy to imagine, understand, and appreciate the benefits of a new technology and to relate these potential benefits to their other concerns.

However, unlike innovators, early adopters are not technologists. Whenever they find a strong match, they are willing to base their buying decisions on it.

Because early adopters do not rely on well-established references in making these buying decisions, preferring instead to rely on their own intuition and vision, they are core to opening up any high-tech market segment.

What Early Majority Care About

The early majority share some of the early adopters’ ability to relate to technology, but they are driven by a strong sense of practicality. They want to see well-established references before investing substantially.

They know that many of these newfangled inventions end up as passing fads, so they are content to wait and see how other people make out before buying in themselves.

Because roughly one-third of the population in most markets belongs to this segment, winning them leads to substantial profits and growth.

What Late Majority Care About

Whereas the early majority are comfortable with their ability to handle a technology product, should they finally decide to purchase it, members of the late majority are not.

Consequently, they wait until something becomes an established standard, and even then, they want to see lots of proof and, therefore, buy from large, well-established companies.

Like the early majority, this group comprises about one-third of the total buying population. Winning them is profitable as the product would have matured by this time, the selling costs would be lower, and virtually all R&D costs would have been amortized.

What Laggards Care About

From a market development perspective, laggards are generally not worth pursuing. They simply don’t want anything to do with the new. The only time laggards ever buy new technology is when it is part of another old product—such as a microchip controlling a refrigerator—and they don’t even know it is there.

Cracks in the Innovation Adoption Curve

A key takeaway from DOI’s adoption curve is that new innovations are absorbed in stages that correspond to the psychological and social profiles of society’s members.

Thus, the way to develop a market for a new product is to work the curve from left to right, making each “captured” group a reference for marketing to the next. The endorsement of innovators attracts early adopters; the early adopters attract the early majority, and so on.

While this process can be thought of as movement across a continuum with well-defined stages, in reality, there are cracks and chasms that firms must overcome:

For firms, this represents a group’s difficulty in accepting a new product if presented in the same way as it was to the group to its immediate left.

Each gap represents a risk where an innovation could lose momentum if the marketing is inconsistent with the group. This means the transition to the next segment never happens, and the profit-margin leadership that happens in the middle of the bell curve is never reached.

The Innovator—Early Adopter Gap

The gap between innovators and early adopters is the first to appear in the bell curve. It occurs when an innovation cannot be readily translated into a major new benefit. The product falls through this crack if the marketing effort cannot convey such benefits.

Segway, for example, was marketed as a revolutionary personal transportation device but failed to find a significant practical application for the average consumer, failing eventually [8].

Likewise, Google Wave was an excellent collaborative engine that provided a unified workspace before the remote work boomed. Yet it ended as a failure because Google itself didn’t know what to do with it or how to pitch it [9].

The key to getting beyond the innovators and winning an early adopter is showing that the new technology enables a strategic leap forward, something never before possible, with intrinsic value that appeals to non-technologists.

The Early Adopter—Early Majority Gap (Crossing the Chasm)

The gap between the early adopters and the early majority is wide, difficult, and aptly called a chasm. It is the most formidable and unforgiving transition that firms must make during the life cycle of any new innovation’s adoption.

It is even more dangerous because the transition is hard to spot.

While the customer list and the order size may look the same, the basis of sale—what has been promised, implicitly or explicitly, and what must be delivered—is radically different across these two customer groups.

By being the first to implement change in their industry, early adopters expect competitive terms such as lower product costs, faster time to market, or more comprehensive customer service.

They expect a radical discontinuity between the old and new ways and are prepared to champion this cause against resistance. Being the first, they are prepared to bear inevitable bugs and glitches in the innovation.

In contrast, the early majority expect productivity improvement in their existing operations through the use of new innovations while minimizing discontinuity with the old ways.

They want evolution, not revolution. They want technology to enhance, not overthrow, the established business methods. They hate to debug issues and expect the innovation to work properly and integrate appropriately with their existing stack.

For example, 3D TVs, initially introduced with much hype and early adoption, failed to gain momentum due to the requirement of uncomfortable, expensive glasses, which early adopters tolerated but was unacceptable to the early majority [10].

Because of these fundamental incompatibilities, early adopters do not serve as good references for the early majority. And because the early majority’s concern is not to disrupt their organizations, good references are critical to their buying decisions.

This leads to a Catch-22 situation where the natural spread of innovation is severely interrupted, and without focused marketing efforts, the diffusion tends to fall apart.

The Early Majority—Late Majority Gap

This is approximately the same in magnitude as the innovator—early adopter gap. By this point in the adoption life cycle, the market is already well developed, and the innovation has been absorbed into the mainstream.

However, one key issue remains—while the early majority were willing and able to become

technically competent, when necessary, the late majority is not. This means the innovation must be made increasingly easier to adopt to continue being successful, or the transition stalls.

Technologies like digital wallets and cloud computing are good examples. While the early majority may have readily embraced these technologies, the late majority expect more assurances and a smoother learning curve before adopting them.

The Late Majority Gap—Laggard Gap

From a practical standpoint, this gap is irrelevant to firms because laggards do not meaningfully participate in embracing innovation. The only relevant marketing function here is neutralizing their negative influence on other groups.

Sources

1. “It took centuries (and vitamins) for doctors to finally stop scurvy”. Popular Science, https://www.popsci.com/health/whats-gotten-into-you-dan-levitt/. Accessed 05 Mar 2025.

2. “The Weinswig Product Watch: Fidget Toys Going Viral.” Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/deborahweinswig/2017/05/19/the-weinswig-product-watch-fidget-toys-going-viral/. Accessed 05 Mar 2025.

3. “Diffusion of Innovation Theory.” Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, https://cjni.net/journal/?p=1444. Accessed 05 Mar 2025.

4. “Crossing the Chasm, 3rd Edition: Marketing and Selling Disruptive Products to Mainstream Customers”. Geoffrey A. Moore, https://www.amazon.com/Crossing-Chasm-3rd-Disruptive-Mainstream/dp/0062292986. Accessed 05 Mar 2025.

5. “The QWERTY keyboard has been around since 1874: Now a ‘keyvolution’ can help you type 5 times faster”. News24, https://www.news24.com/news24/tech-and-trends/news/the-qwerty-keyboard-has-been-around-since-1874-now-a-keyvolution-can-help-you-type-5-times-faster-20230710. Accessed 05 Mar 2025.

6. “What drives social contagion in the adoption of solar photovoltaic technology?”. The Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/what-drives-social-contagion-in-the-adoption-of-solar-photovoltaic-technology/. Accessed 05 Mar 2025.

7. “Study: Culture influences mask wearing”. MIT News, https://news.mit.edu/2021/masks-collectivism-covid-culture-0520. Accessed 05 Mar 2025.

8. “The Demise Of The Segway Is A Cautionary Tale For Technological Optimists”. Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaellynch/2020/06/29/the-demise-of-the-segway-is-a-cautionary-tale-for-technological-optimists/. Accessed 07 Mar 2025.

9. “The Google Wave That Crashed”. Tech Crunch, https://techcrunch.com/2010/08/10/google-wave-death/. Accessed 07 Mar 2025.

10. “The Real Reasons The 3D TV Was A Failure”. Slashgear, https://www.slashgear.com/890760/the-real-reasons-the-3d-tv-was-a-failure/. Accessed 07 Mar 2025.

11. “Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition”. Everett M. Rogers, https://www.amazon.com/dp/0743222091. Accessed 07 Mar 2025.