Most companies today practice some form of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) to contribute to the well-being of the community and society they affect and depend on. This is evident from the fact that over 95% of S&P 500 companies publish an annual CSR report [1].

CSR is clearly important. 70% of Americans believe it’s either “somewhat” or “very important” for companies to improve the world, and as consumers, they are motivated to purchase from such companies. In contrast, just 37% believe it’s most important for a company to make money [2].

Because CSR is a broad term, many related ideas, such as environmental, social, and governance (ESG), sustainability, corporate citizenship, and triple bottom line (TBL), overlap in scope and intention.

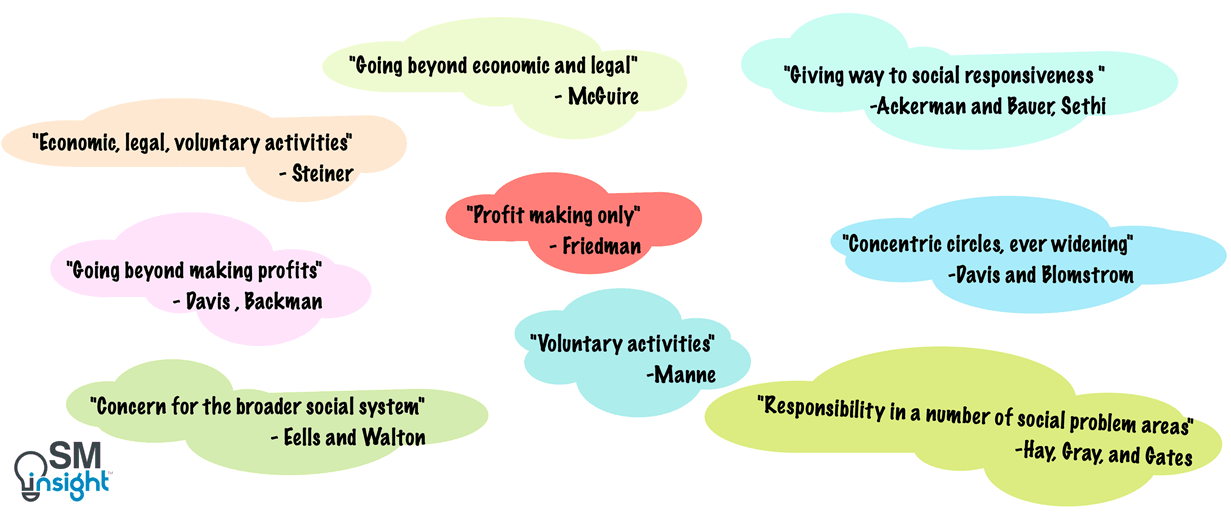

One of the challenges in understanding the concept of CSR is simply identifying a consistent and sensible definition from a bewildering range of ideas and definitions proposed in the literature. One study published in 2006 identified and analyzed 37 different definitions of CSR, and it did not even capture all of them [3].

Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR is a four-part definition of CSR that remains one of the most popular frameworks for understanding a company’s responsibilities toward society. It defines CSR as:

“Corporate social responsibility encompasses the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary (philanthropic) expectations that society has of organizations at a given point in time.” [4]

Carroll’s Pyramid is popular because of its simplicity and the structure it provides organizations to meet their business’s economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic demands. It brings consistency to a field that otherwise lacks a clear, set definition.

A Brief History of CSR

In its modern formulation, CSR has been an important and progressing topic since the 1950s. In 1953, American economist Howard R. Bowen first discussed this in his book “Social Responsibilities of the Businessmen.” In it, he questioned companies’ responsibility to give back to society [5].

Many of the early definitions of CSR were rather general. For example, in the 1960s, it was defined as “seriously considering the impact of the company’s actions on society.” Another read, “Social responsibility is the obligation of decision makers to take actions which protect and improve the welfare of society along with their own interests.” [6]

In general, CSR was typically understood as policies and practices that business people employed to be sure that society or stakeholders other than business owners were considered and protected in their strategies and operations.

It was not until the significant social legislation of the early 1970s, when the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) were created, that this message became indelibly clear.

These new governmental bodies recognized the environment, employees, and consumers as significant and legitimate business stakeholders. Since then, corporate executives have had to balance their commitments to shareholders with their obligations to an ever-broadening group of stakeholders with legal and ethical rights.

Despite these developments, CSR lacked a consistent definition and was conceptualized in several different ways by writers of stature in business:

Some prominent thinkers have even been critical of CSR. For example, in a 1958 Harvard Business Review article, Theodore Levitt spoke of “The Dangers of Social Responsibility,” while Milton Friedman argued that social issues are not the concern of businesspeople [8].

In 1991, Professor Archie Carroll created a graphic definition of CSR. He simplified this nuanced topic using a single pyramid diagram, which, since then, has been the most durable and widely cited CSR definition.

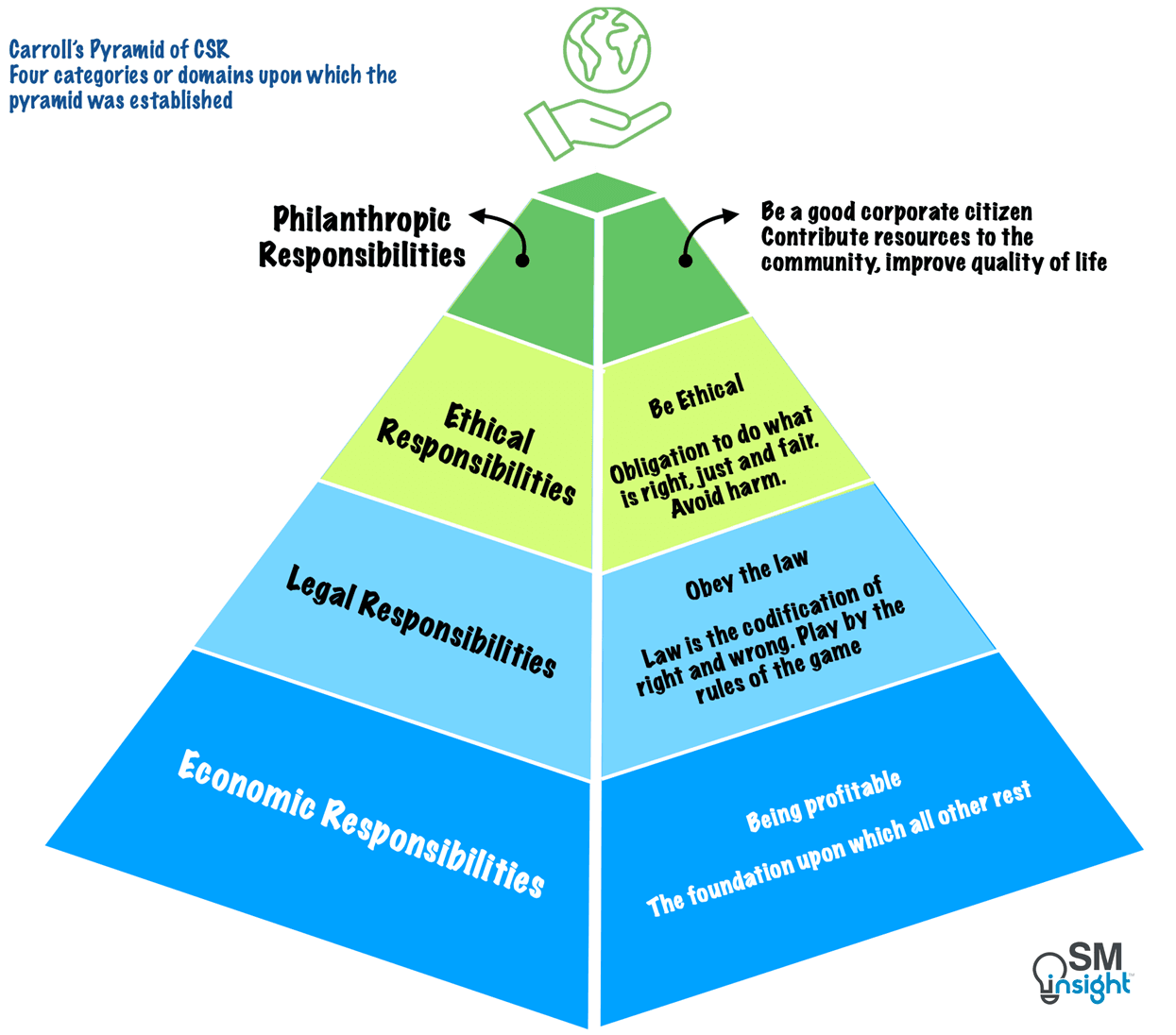

Components of Carroll’s Pyramid

The pyramid portrays four components of CSR, beginning with the basic building block notion that economic performance undergirds all else. At the same time, businesses are expected to obey the law because the law codifies acceptable and unacceptable behavior within a society.

Next is the business’s responsibility to be ethical. At its most fundamental level, this is the obligation to do what is right, just, and fair and to avoid or minimize harm to stakeholders (employees, consumers, the environment, and others).

Finally, businesses are expected to be good corporate citizens. This is captured in philanthropic responsibility, wherein businesses are expected to contribute financial and human resources to the community to improve the quality of life.

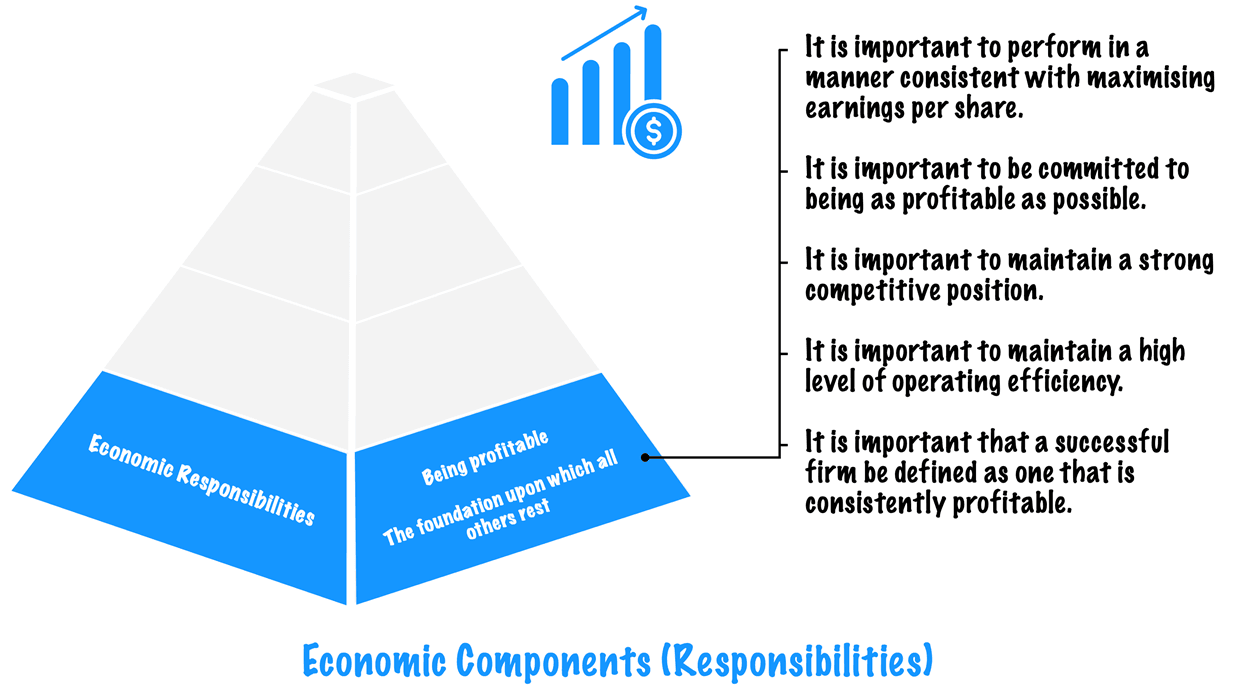

Economic Responsibilities

Economic responsibilities form the foundation of the pyramid. This is because business organizations, before anything else, are economic entities designed to provide goods and services to societal members, with profit being the primary incentive for entrepreneurship.

The primary role of any for-profit business is to provide goods and services that meet consumer needs while generating a satisfactory profit.

In many companies today, the focus on profit has evolved into a pursuit of maximizing profits, which has become a core and enduring value. All other business responsibilities are predicated upon the economic responsibility of the firm because, without it, the others become moot considerations.

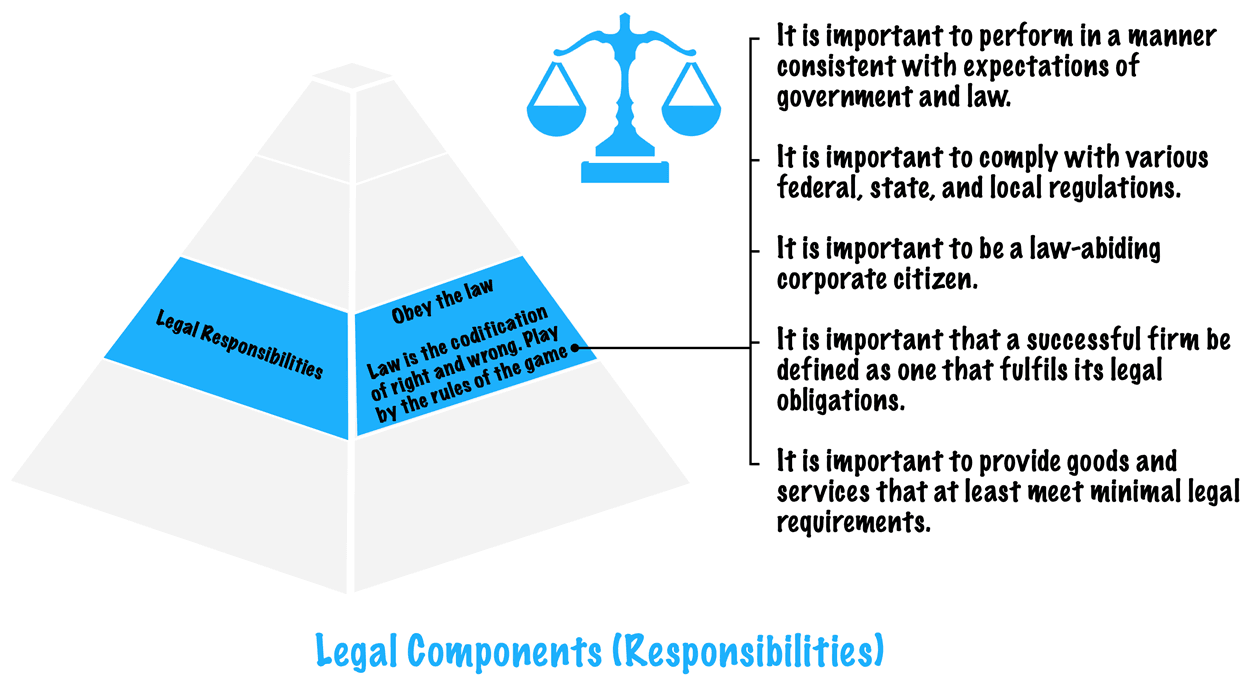

Legal Responsibilities

As part of the “social contract” between business and society, firms are expected to pursue their economic missions within the framework of the law, which embodies the basic notions of fairness established by lawmakers.

Hence, legal forms the second layer of the pyramid and coexists with economic responsibilities as fundamental precepts of the free enterprise system.

Businesses are expected to operate not only based on profit motives but also comply with the laws and regulations promulgated by federal, state, and local governments.

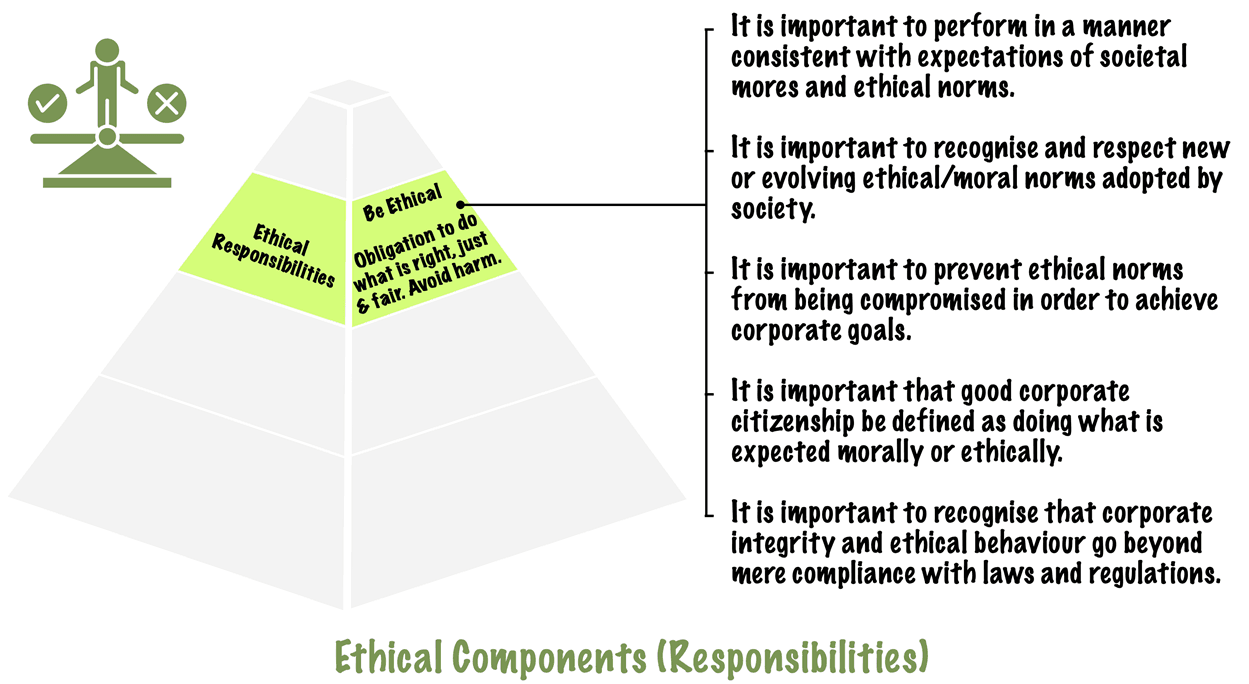

Ethical Responsibilities

Ethical responsibilities embrace those activities and practices expected or prohibited by societal members even though they are not codified into law.

These are standards, norms, or expectations that stem from concern about what consumers, employees, shareholders, and the community regard as fair, just, or in keeping with the respect or protection of stakeholders’ moral rights.

In one sense, changing ethics or values precede the establishment of law because they become the driving force behind the very creation of laws or regulations.

For example, in the 1970s, increasing public concern for the environment, driven by rising awareness of pollution and ecological harm, led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and laws like the Clean Air Act [9].

Several examples of companies operating at the “good” and the “bad” end of the ethical spectrum exist.

For example, in 1982, in the space of a few days, when seven people died in Chicago consuming cyanide-laced capsules of Tylenol made by Johnson & Johnson, the company, without hesitation, recalled 31 million bottles of the drug and offered replacement products in the safer tablet form free of charge [10].

Starbucks’s ethical sourcing of sustainable products is another positive example. The coffee brand links its success to the success of the farmers and suppliers who grow and produce its products. It provides holistic support through loans, training, supply of disease-resistant trees, and more [11].

Boeing’s handling of the 737 Max 8 crashes in 2018 highlights a concerning ethical lapse. Despite known software flaws that compromised pilot control, and following the tragic crash of Lion Air flight—where a Max 8 aircraft plunged into the ocean, claiming 189 lives—Boeing continued to assert the airworthiness of its aircraft, leading to the catastrophic crash of Ethiopian Airlines flight 302, which resulted in the loss of 157 lives [12].

Though the law was followed in all three examples, Boeing’s contrasting responses show that adherence to the law is not always sufficient; ethical leadership and a commitment to doing what is right are equally essential.

Ethical responsibilities often reflect a higher performance standard than that currently required by law. They are often ill-defined or continually under public debate as to their legitimacy, making them difficult for businesses to deal with.

The business ethics movement of the past decades has firmly established ethical responsibility as a legitimate CSR component. Though depicted as a separate layer of the CSR pyramid, it is in dynamic interplay with the legal responsibility, constantly pushing the legal responsibility to broaden or expand while at the same time placing ever higher expectations on businesspersons to operate at levels above that required by law.

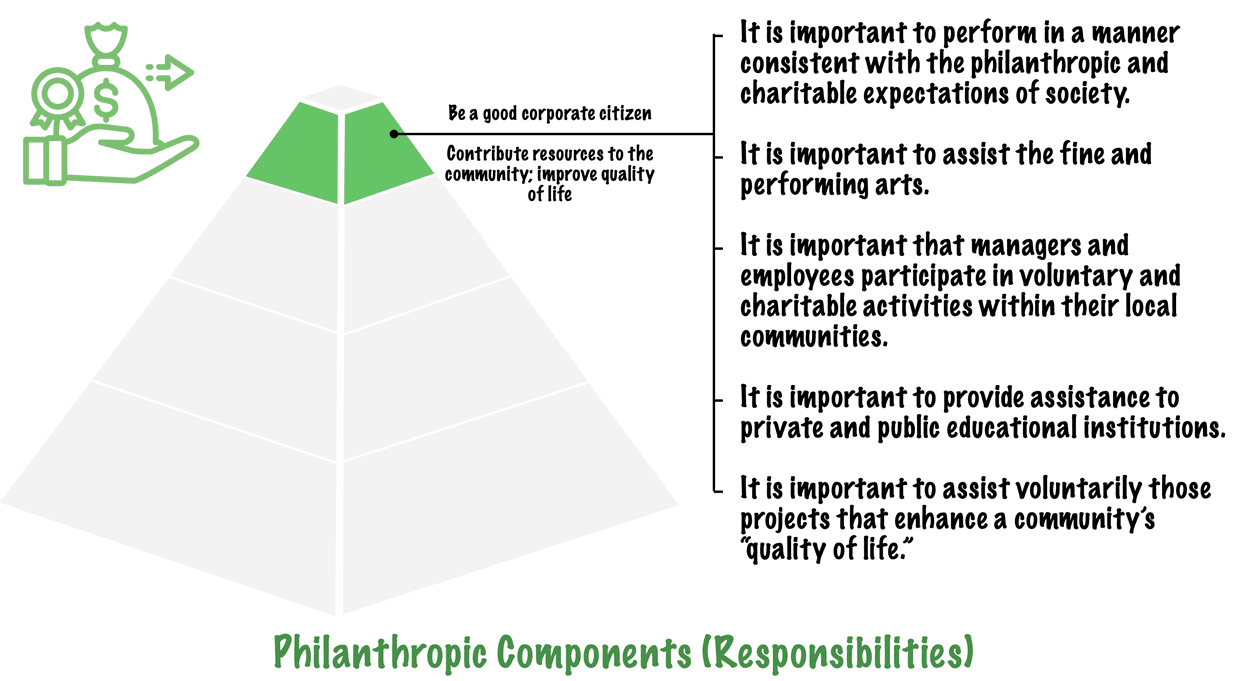

Philanthropic Responsibilities

Philanthropy responsibilities encompass corporate actions that align with society’s expectation that businesses should be good corporate citizens. This includes actively engaging in acts or programs to promote human welfare or goodwill.

The distinguishing feature between philanthropic and ethical responsibilities is that the former is not ethically or morally expected. Communities desire firms to contribute their money, facilities, and employee time to humanitarian programs or purposes, but not doing so is not regarded as unethical.

Philanthropy is more discretionary or voluntary. We have had many recent examples of companies taking this seriously.

In 2022, Patagonia’s founder, Yvon Chouinard, made headlines by donating his family’s $3 billion company and its future profits to fight climate change. Since then, about $71 million of the clothing company’s earnings have been used to fund wildlife restoration, dam removal, and democratic groups [13].

The distinction between ethical and philanthropic initiatives in the CSR pyramid brings home the vital point that CSR includes philanthropic contributions but is not limited to them. While philanthropy is highly desired and prized, it is actually less important than the other three categories of social responsibility.

In a sense, philanthropy is icing on the cake—or the pyramid, in this case.

Putting It together

The CSR pyramid is intended to portray that CSR comprises distinct components that, taken together, constitute the whole. When seen separately, they help managers see the different types of obligations in constant but dynamic tension with each other.

Though these four components are discussed separately, they are not mutually exclusive and are not intended to juxtapose a firm’s economic responsibilities with its other responsibilities.

Often, the most critical tensions an organization faces are between economic and legal, economic and ethical, and economic and philanthropic considerations. While these are seen as a conflict between a firm’s “concern for profits” and “concern for society,” this represents an oversimplification.

A CSR or stakeholder perspective must recognize these tensions as organizational realities yet focus on the pyramid as a unified whole when engaging in decision-making. To state it simply, a CSR firm must strive to make a profit, obey the law, be ethical, and become a good corporate citizen.

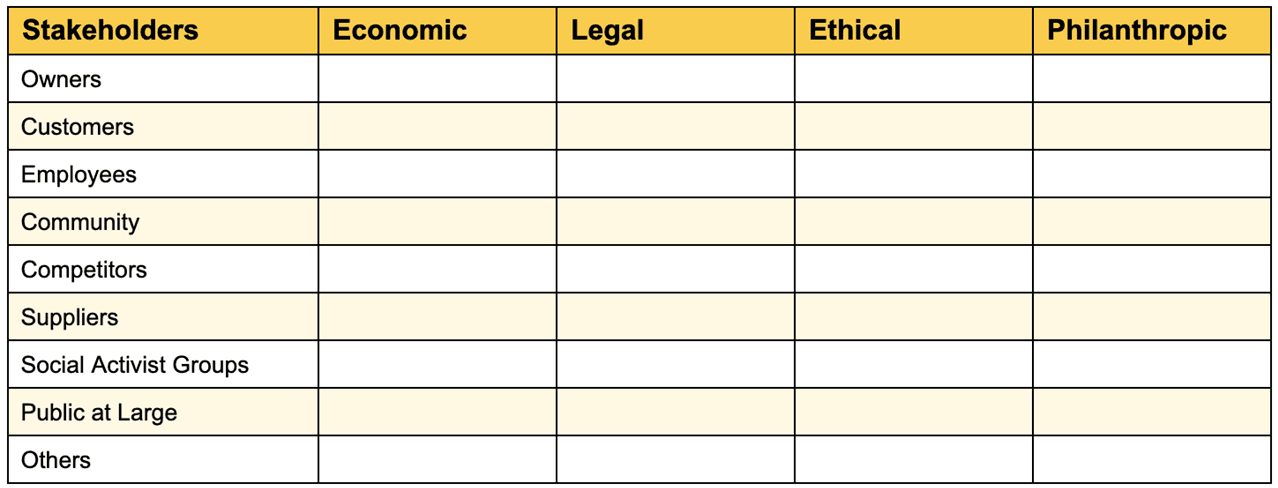

Deciding Stakeholder Importance Using the CSR Pyramid

Stakeholders are groups or individuals with a stake, claim, or interest in the firm’s operations and decisions. Sometimes, the stake represents a legal claim, such as that held by an owner, an employee, or a customer with an explicit or implicit contract. Other times, it might represent a moral claim, such as a right to be treated fairly.

Numerous stakeholder groups (shareholders, consumers, employees, suppliers, community, social activist groups) may be clamoring for management’s attention at any moment. The challenge is deciding which stakeholders merit attention and consideration.

Two vital criteria to decide this are stakeholders’ legitimacy and their power.

Legitimacy refers to the extent to which a group has a justifiable right to make its claim. For example, a group of employees advocating safer working conditions has strong legitimacy, as their claim directly relates to their fundamental right to health and safety.

Power refers to the degree of influence stakeholders can exert over the firm and can vary among different stakeholder groups. For instance, individual shareholders have minimal influence unless they organize collectively, while institutional investors or large mutual fund groups possess substantial influence.

From a CSR perspective, legitimacy is most important, but from a management perspective, power is of central influence. To decide relative importance, a firm must answer an important question: What kind of social responsibilities does a firm have toward its stakeholders?

The stakeholder responsibility matrix, which is based on the CSR pyramid, helps answer this question:

This matrix can be used as an analytical tool to organize thoughts and ideas about what the firm should be doing economically, legally, ethically, and philanthropically with respect to its identified stakeholder groups.

By carefully and deliberately moving through the various cells of the matrix, managers can develop a descriptive and analytical database that can then be used for stakeholder management. The information from this analysis is useful for developing priorities and making long-term and short-term decisions involving multiple stakeholders’ interests.

Management Approach to Ethics

The link between a firm’s ethical responsibilities and its major stakeholder groups can be explored by isolating the ethical component of the CSR pyramid and examining it in the context of three major management approaches commonly seen across firms: immoral management, amoral management, and moral management.

| Immoral Management | Amoral Management | Moral Management | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Norms | Active opposition to what is moral. Decisions are discordant with accepted ethical principles | Management is neither moral nor immoral. Lacks ethical perception and moral awareness | Management activity conforms to a high standard of ethical or right behavior. Ethical leadership is common-place on the part of the management |

| Motives | Selfish, care only about organization’s gains | Well-intended but selfish in the sense that impact on others is not considered | Management wants to succeed but only within the confines of sound ethical precepts (fairness, justice, due process) |

| Goals | Profitability and organizational success at any cost | Profitability. Other goals are not considered. | Profitability within the confines of legal and high ethical standards. |

| Orientation toward the Law | Legal standards are seen as barriers | Law is the ethical guide. Preferably the letter of the law. The central question is, what can we do legally? | Follow the law by the letter and the spirit. |

| Strategy | Exploit opportunities for corporate gain. Cut corners wherever useful. | Managers are given free rein. Personal ethics may apply only when managers choose to. Respond to legal mandate only when caught | Live by sound ethical standards. Assume leadership position when ethical dilemmas arise |

Immoral Management

Immoral management is characterized by managers whose decisions, actions, and behavior suggest an active opposition to what is deemed right or ethical. Such decisions are discordant with accepted ethical principles and imply an active negation of what is moral.

Exxon, for example, downplayed its role in the climate crisis for decades in public messaging. It sold consumers a product that it knew was dangerous while publicly denying or downplaying those dangers. Today, when the dangers are no longer deniable, it denies responsibility and blames the consumer [14].

Managers in this category care only about their or their organization’s profitability and success. They see legal standards as barriers or impediments that management must overcome to accomplish what it wants. Their strategy is to exploit opportunities for personal or corporate gain.

Amoral Management

Amoral managers are neither immoral nor moral but are insensitive to the fact that their everyday business decisions may have deleterious effects on others. They lack ethical perception or awareness and give little importance to the ethical dimension.

While well-intentioned, these managers do not see that their business decisions and actions may hurt those with whom they transact business or interact. Typically, their orientation is towards the letter of the law, which serves as their ethical guide.

Amoral behavior can be unintentional or intentional. Unintentional amoral managers believe that ethical considerations belong to private life, not business, and think business activities lie outside moral judgment. Intentional amoral managers consciously disregard the role of ethics in business.

Uber’s management, for example, exploited drivers by treating them as independent contractors to avoid paying benefits and keep labor costs low. Because of this arrangement, Uber could not mandate drivers to work at specific times or locations. The ride-hailing firm compensated for this lack of control by using psychological tactics to influence when, where, and how long drivers worked, often encouraging them to work longer in less profitable locations or timings. [15]

Moral Management

Moral managers employ ethical norms that adhere to a high standard of right behavior. They conform to high levels of professional conduct and exemplify leadership on ethical issues. They want to be profitable, but only within the confines of sound legal and ethical precepts such as fairness, justice, and due process.

Moral managers see the law as a minimal ethical requirement, and their preference and goal is to operate well above what the law mandates. They seek out and use sound ethical principles such as justice, rights, and utilitarianism to guide their decisions. When ethical dilemmas arise, they assume a leadership position for their companies and industries.

Starbucks, for example, closed more than 8,000 U.S. stores for an afternoon of racial bias training for 175,000 employees following an incident when two black men were arrested after asking to use a Philadelphia Starbucks restroom without making a purchase. This move cost it $12 million [16].

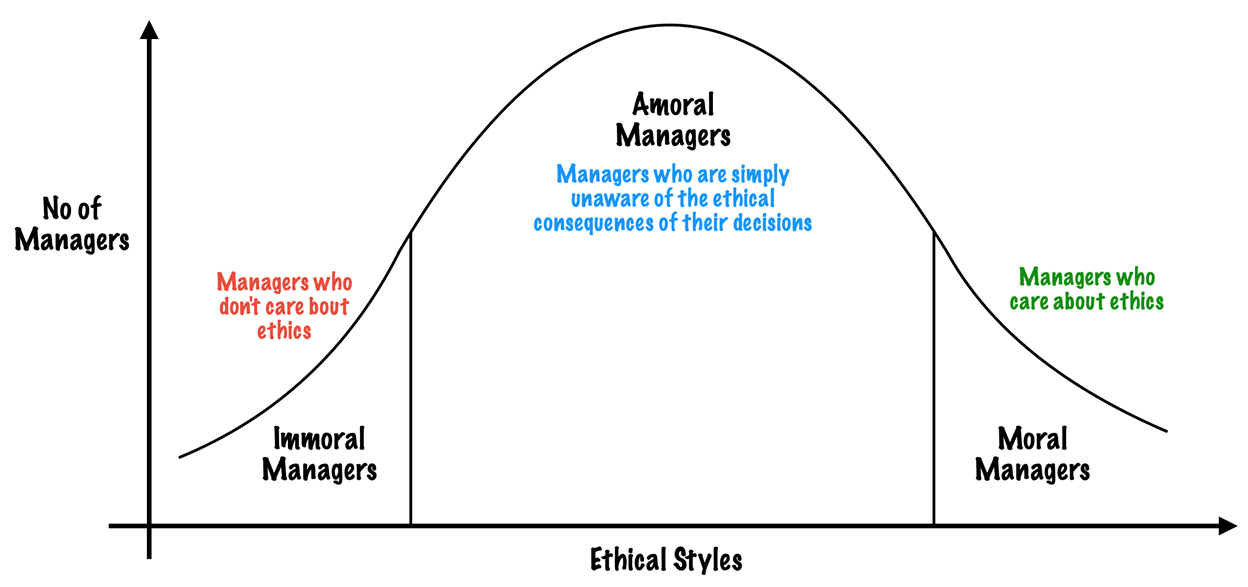

Population Distribution of Management Approaches Hypothesized by Carroll

Based on reports of management behavior, studies of ethics, and experience in teaching ethics in executive development programs, Carroll asserted that most managers behave “immorally” or “amorally” – which is to say the majority do not think beyond themselves:

Though Carroll did not specify the exact proportion of managers in each category, this assertion may seem disheartening. However, the fact that many managers fall into the Amoral category—unaware of their impacts on others—provides hope for improvement.

Carroll suggested that managers must undergo a paradigm shift from viewing the organization as a purely economic or legal entity to one with a multitude of responsibilities, the principal among them being ethical responsibility. They must appreciate six key elements in making moral judgments, which are:

- Moral imagination: The ability to perceive that a web of competing economic relationships is, at the same time, also a web of moral and ethical relationships.

- Moral identification and ordering: The ability to discern the relevance or non-relevance of moral factors introduced in decision-making situations and to rank or order them just as with economic or technological issues.

- Moral evaluation: Once the issues have been identified and ordered, managers must become skilled at evaluating and judging them. They must understand the importance of clear principles and the process of weighing ethical factors and develop an ability to identify a decision’s economic and moral implications.

- Tolerance of moral disagreement and ambiguity: Discussions about ethics are often accompanied by disagreements and ambiguity, which managers must learn to accept.

- Integration of managerial and moral competence: Managers must realize that moral issues in management are not distinct from traditional business decisions.

- A sense of moral obligation: Managers must develop a sense of moral obligation and integrity. This requires an intuitive and learned understanding that concern for fairness, justice, and due process toward people, groups, and communities are woven into the fabric of managerial decision-making that holds the system together.

Sources

1. “All-Time High of Sustainability Reports Among U.S. Publicly-Traded Companies: 96% of S&P 500 and 81% of Russell 1000.”. G&A Institute, https://www.ga-institute.com/research/research/sustainability-reporting-trends/2022-sustainability-reporting-in-focus/. Accessed 29 Apr 2025.

2. “15 Eye-Opening Corporate Social Responsibility Statistics”. HBR Business Insights, https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/corporate-social-responsibility-statistics. Accessed 30 Apr 2025.

3. “How Corporate Social Responsibility Is Defined: An Analysis of 37 Definitions”. Alexander Dahlsrud, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227663040_How_Corporate_Social_Responsibility_Is_Defined_An_Analysis_of_37_Definitions. Accessed 20 Apr 2025.

4. “The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders.” Archie B Carroll, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/4883660_The_Pyramid_of_Corporate_Social_Responsibility_Toward_the_Moral_Management_of_Organizational_Stakeholders. Accessed 21 Apr 2025.

5. “Social responsibilities of the businessman.” Howard R. Bowen, https://uipress.uiowa.edu/books/social-responsibilities-businessman. Accessed 20 Apr 2025.

6. “Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: taking another look.” Archie B. Carroll, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304662992_Carroll’s_pyramid_of_CSR_taking_another_look. Accessed 21 Apr 2025.

7. “A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance”. Archie B Carroll, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303179257_A_Three-Dimensional_Conceptual_Model_of_Corporate_Performance. Accessed 30 Apr 2025.

8. “The Dangers of Social Responsibility”. Theodore Levitt, https://57ef850e78feaed47e42-3eada556f2c82b951c467be415f62411.ssl.cf2.rackcdn.com/Levitt-1958-TheDangersofSR.pdf. Accessed 21 Apr 2025.

9. “From Earth Day 1970 to 2022: A story of progress”. Environment America Research & Policy Center, https://environmentamerica.org/center/articles/earth-day-1970-2022-story-progress/. Accessed 29 Apr 2025.

10. “Tylenol made a hero of Johnson & Johnson: The recall that started them all.” The NewYork Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2002/03/23/your-money/IHT-tylenol-made-a-hero-of-johnson-johnson-the-recall-that-started.html. Accessed 29 Apr 2025.

11. “Building a Sustainable Future for Coffee, Together.” Starbucks, https://stories.starbucks.com/press/2019/building-a-sustainable-future-for-coffee-together/. Accessed 30 Apr 2025.

12. “A Complete Timeline of the Boeing 737 Max Disaster”. Rollingstone, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/boeing-737-max-disasters-timeline-1235007089/. Accessed 29 Apr 2025.

13. “Patagonia’s Profits Are Funding Conservation — and Politics.” The NewYork Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/30/climate/patagonia-holdfast-philanthropy.html. Accessed 29 Apr 2025.

14. “Fury after Exxon chief says public to blame for climate failures.” The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/mar/04/exxon-chief-public-climate-failures. Accessed 30 Apr 2025.

15. “How Uber Uses Psychological Tricks to Push Its Drivers’ Buttons”. NewYork Times, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/04/02/technology/uber-drivers-psychological-tricks.html. Accessed 30 Apr 2025.

16. “What Starbucks got wrong — and right — after Philadelphia arrests.” MIT Management Sloan School, https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/what-starbucks-got-wrong-and-right-after-philadelphia-arrests. Accessed 30 Apr 2025.

17. “In Search of the Moral Manager”. Archie B Carroll, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/4883143_In_Search_of_the_Moral_Manager. Accessed 31 Apr 2025.