Organizational health matters more today than ever. Not only is it correlated with long-term performance, but it is also causal to it [1]. To win, leaders must leverage an organization’s distinctive strengths and address weaknesses. However, diagnosing an organization’s health is a challenging undertaking, given the countless possible parameters at play.

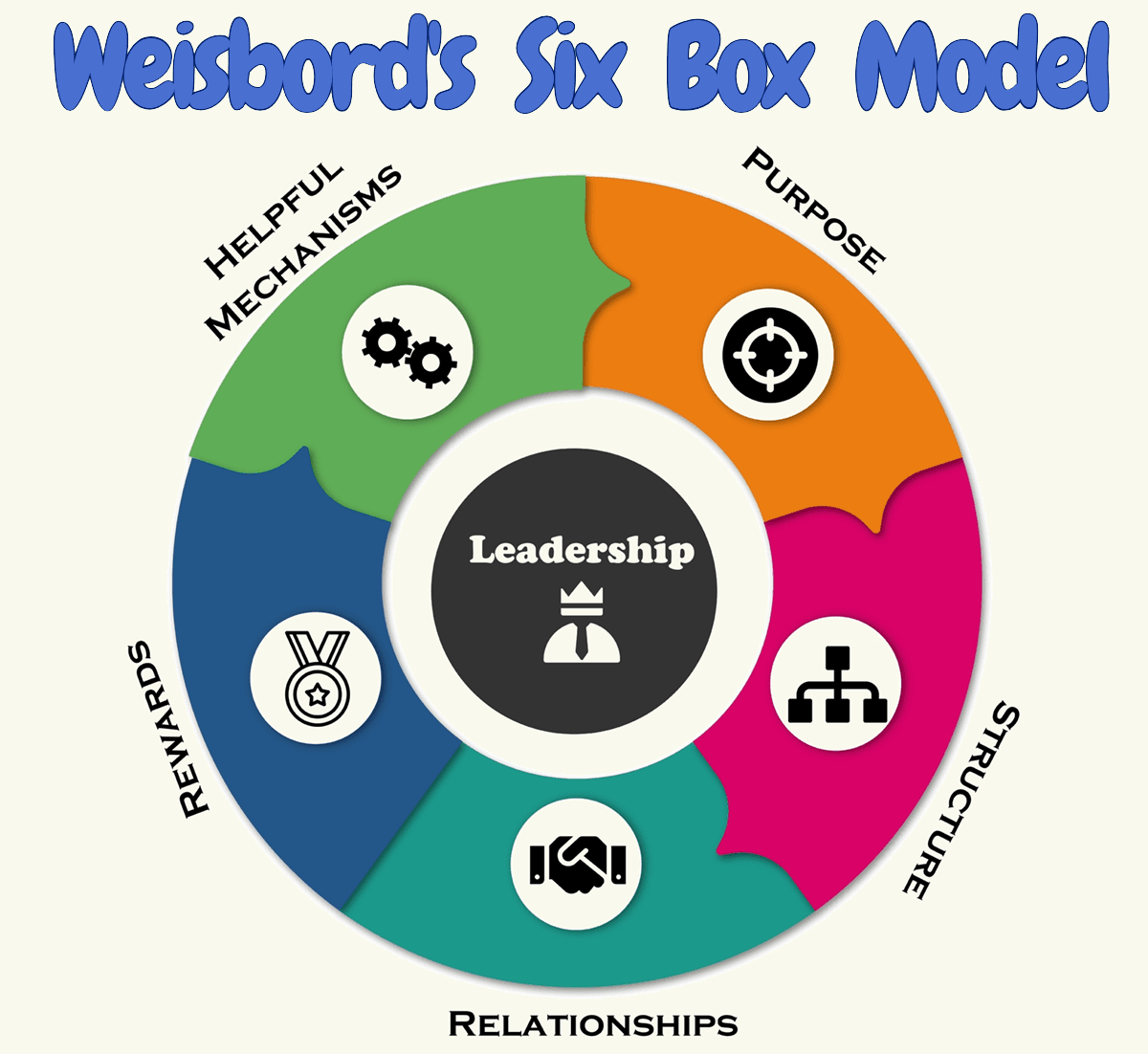

The Six-Box Model—Purpose, Structure, Relationships, Rewards, Helpful Mechanisms, and Leadership—is a practical organizational assessment tool that provides a snapshot of an organization’s current state. It is widely used to analyze organizations, diagnose issues, and improve performance.

The model attempts to build an organization’s “cognitive map” by providing six labels under which much of the formal and informal activities can be clubbed. It allows issues to be seen as blips in one or more of the six boxes and helps address them through focused efforts.

Similar to how air controllers use radar to chart the course of aircraft—height, speed, distance apart, and whether—those seeking to improve an organization can use the six boxes to observe what is going on in and between each box, which forms the basis for organizational diagnosis.

Weisbord’s Six-Box Model

Organizational consultant and researcher Marvin Weisbord [2] introduced the six-box model in his 1976 paper, Organizational Diagnosis: Six Places to Look for Trouble. He elaborated further on the framework in his 1978 book, Organizational Diagnosis: A Workbook of Theory and Practice [3] [4].

It has since influenced notable organizational development practitioners, including Nadler and Tushman, Tichy, and Burke and Litwin, who developed approaches based on the six-box model [5]. The following visual outlines the six-box model:

The model helps shed light on both formal and informal systems in six key areas where things must work in an internally consistent fashion. The greater the gap between these six areas, the less effective the organization will be.

0. The Boundary and the Environment

The outer circle (in blue) represents the organization’s boundary. Anything outside is the “environment,” representing forces and events that are difficult to control from within. The environment impacts the organization and demands a response from it.

Examples include customers, government, competitive forces, or events. Although it may not always be clear where an organization’s boundary lies, for the purpose of diagnosis, a boundary must be defined, and it could mean a company, a department, or a business unit.

Before a diagnosis, it is also helpful to chart and list important units, individuals, or functions within the chosen boundary, making it clear who is inside, who is out, and how many levels of organization are included.

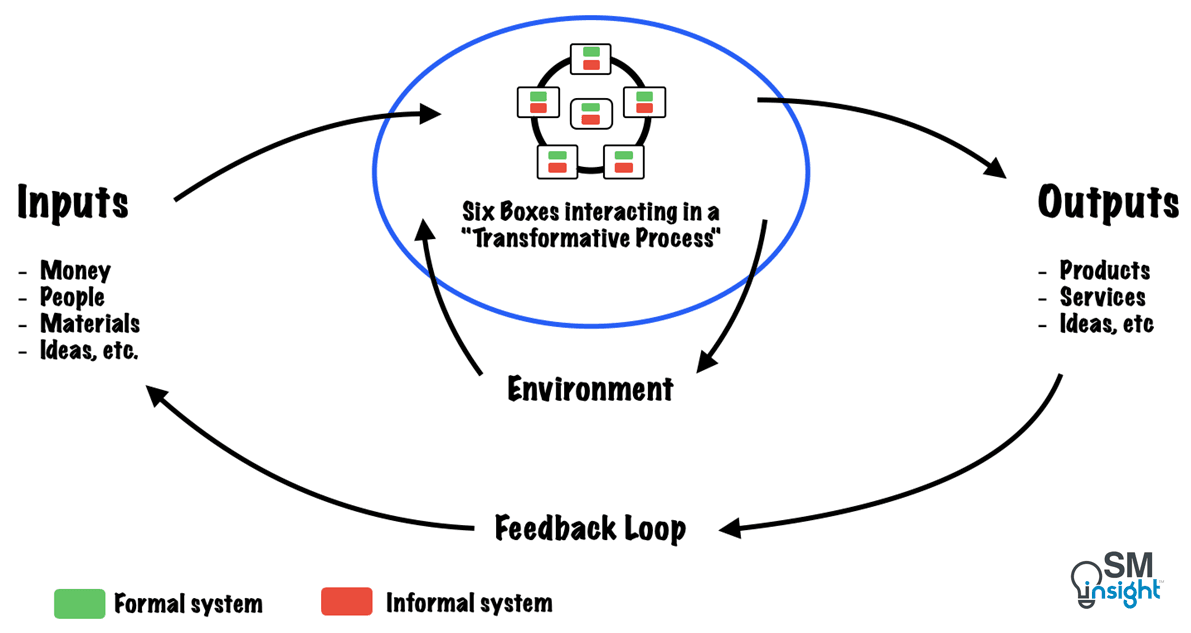

Within the chosen boundaries, the six boxes interact in what is known as an input/output system that transforms resources into goods or services as shown:

Formal and Informal Systems

In each of the six boxes, there are two systems at work. The first is the formal system on paper, while the second is the informal one—what people actually do.

Diagnosing the formal system requires informed guessing. The informed part is knowing the facts—what the organization says in its statements, reports, charts, graphs, and speeches about how it’s organized. The guessing part is comparing that rhetoric to its environment and gauging whether it is consistent with its environment.

Informal system diagnosis focuses on the frequency with which people take specific actions and their importance on organizational performance. Informal systems determine whether otherwise technically excellent systems will succeed or fail.

Not all norms can be changed with formal systems. Hence, it is crucial to study relationships between formal and informal systems to uncover why the input-output transformation streams don’t flow as smoothly as they could.

External Domains

Every organization is influenced by sources of support and restraint that exert pressure from the outside. Organizations struggle to reduce uncertainties at each of these contact points (also known as “domains” in open systems theory):

- Customers (distributors and/or users)

- Suppliers (of materials, capital, equipment, space)

- Competitors (for both markets and resources)

- Regulatory groups (government, unions, trade associations, certifying groups)

- Parent organizations (central headquarters, university, etc.)

Each of the six boxes is continually juggled to keep up with shifting, uncertain winds in these external domains. Poor relations with one or more domains can strain internal relationships, structure, rewards, leadership, etc. Conversely, internal issues can also strain relations with one or more domains.

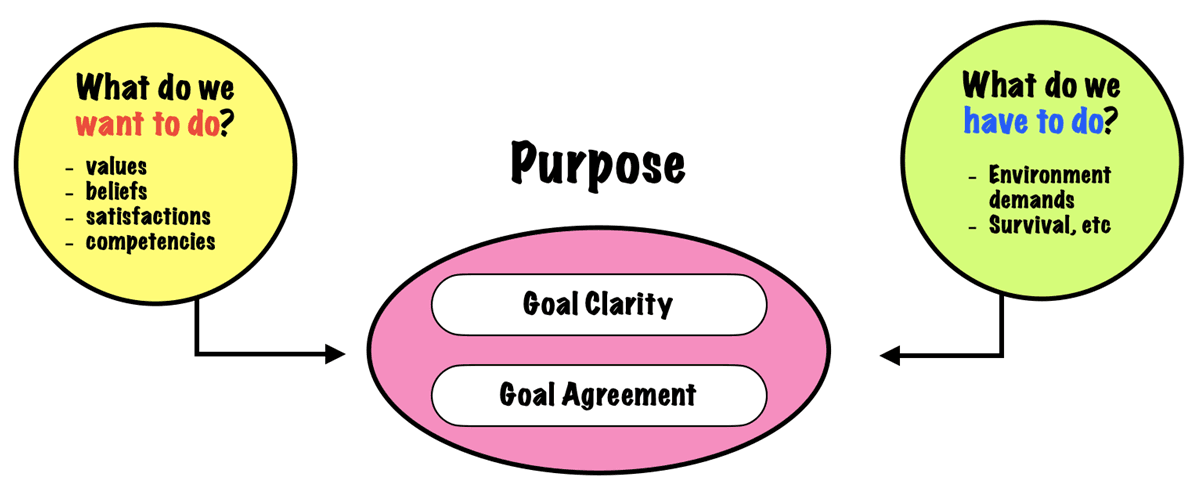

1. Purpose

Purpose represents the “core mission” or “core transformation process” the organization aims to undertake. A well-defined purpose defines the boundaries around activities that are (and are not) appropriate for the organization. It helps the organization cope with uncertainty.

Purpose consists of two critical factors: goal clarity and goal agreement. It results from a psychological negotiation between “what we want to do” (values, beliefs, satisfactions, competencies) and “what we have to do” (demands of the environment, survival needs, etc.).

This negotiation occurs irrespective of whether people consciously discuss it and leads to a set of priorities that make up the organization’s agenda. Such priorities can be identified by observing what people spend their time, energy, and money on, irrespective of what they say is important.

Purpose also highlights the organization’s unique feature, differentiating it from the competition. People working for an organization must accept its core purposes as a part of the contract.

When the purpose is vague, conflicts can arise. Poorly defined or overly broad purposes strain relations with producers and consumers alike as they disperse focus and concentration. Hence, during a diagnosis, it is important to examine the following:

- Goal fit—how appropriate is the purpose to the organization’s environment? Is there enough consumer support to ensure its validity?

- Goal clarity—is the stated purpose concrete enough to guide the organization into what activities to include and exclude?

- Goal agreement—To what extent do people exhibit agreement with the stated goals (including in their informal behaviors)?

In the long run, changing trends, technology, practices, and markets will force every organization to question its purpose. People will be forced to reconsider their organization’s purpose and actions as they gain new insights.

For example, Amazon went from being the “Earth’s Biggest Bookstore” to “Earth’s most customer-centric company.”

When using the Six Box Model in organizational diagnosis, the purpose box directs attention to how the organization conceptualizes its work and whether there are other ways to improve its fit with the environment, clarify its goals, and gain higher goal agreement.

Diagnosing the Purpose

An organization’s formal and informal systems must be scanned to determine how well its purpose guides its actions.

The formal system can be assessed using the following questions:

- What documents, if any, concretely define the organization’s purposes?

- Based on those documents, what are the formal, central purposes supposed to be?

- In the context of environmental demands, how congruent are they with the organization’s formal environment?

- How good is the fit between stated purposes and consumer needs?

The informal system can be assessed using the following questions:

- Do people understand the organization’s purposes the same way?

- To what degree do people perceive the organization’s activities or goals as serving purposes different from those stated? What is the degree of mismatch?

- Are there observable behaviors that tend to contradict formal purposes, showing a lack of clarity or agreement?

- If the organization’s stated purposes were to be reframed, what statement might gain a better fit with the environment, a greater goal clarity, and a higher commitment

2. Structure

Although there are more forms of organizational structures today, when developing the Six Boxes Model, Marvin considered three types of structures: (1) function-based, (2) product-based, and (3) a mixture of both, called matrix structures.

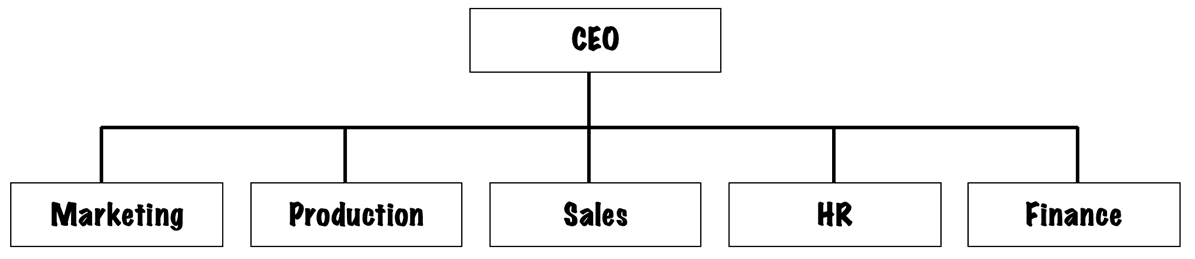

Functional Structure

In a functional structure (shown below), the division of labor, budgets, promotions, and rewards are competence-based. Functional bosses have the most influence and seek to maximize their own goals, not necessarily those of the organization.

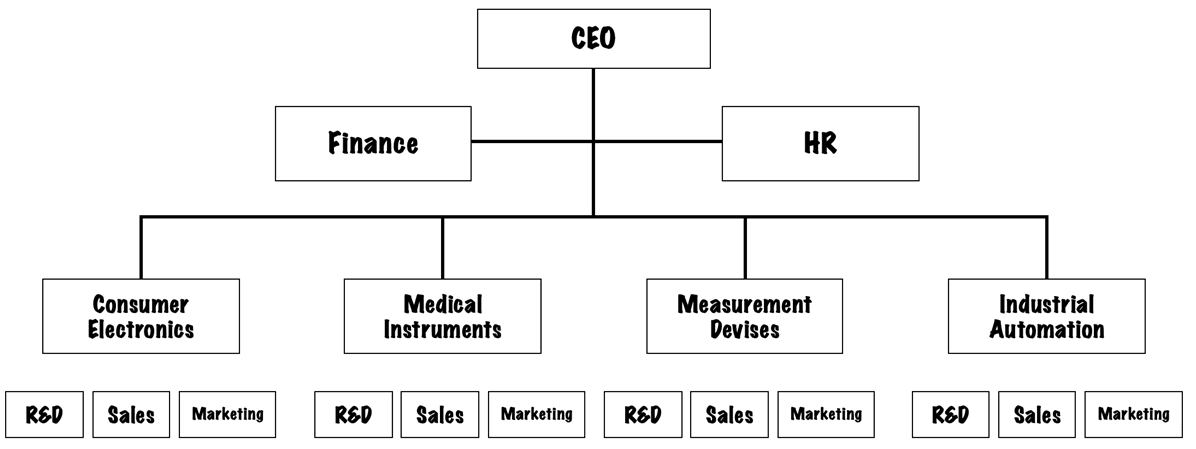

Product Structure

A product structure is ideal when coordination with other teams is minimal. It best suits those who can quickly integrate resources to innovate, produce, and deliver a product or service. In a product structure, team managers have the most influence.

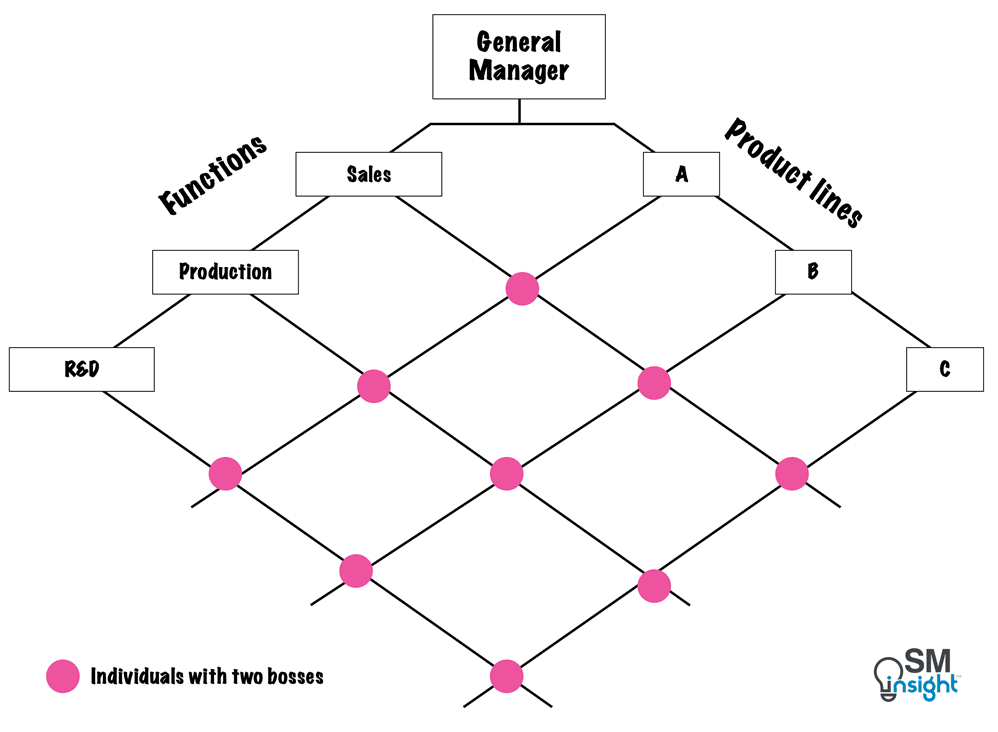

Matrix Structure

In a matrix structure, people report to two or more formal locations on the chart.

Structures Compared

Each of these three structures has its strengths, drawbacks, and highlights, as shown:

| Type of Structure | Strengths | Drawbacks | Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Structure | (1) Support for in-depth competence. People in each function ‘talk the same language. (2) There is freedom to specialize and maximize what you do best. (3) People feel stable and secure, particularly in environments where change is slow and quick response is not essential. | (1) Intergroup conflict is predictable. (2) Big decisions pile up at the top. (3) Few members have the “big picture” view. (4) It’s tough to quickly shift directions. (5) Functional heads focus on local optimization and don’t readily see the big picture | Functional organizations are not suited for rapid change. Functional structures are more bureaucratic. |

| Product structure | (1) Responsive to rapid change in environment or technologies. (2) Less likely to have inter-group conflicts. (3) Easier for team members to see the organization’s goals. (4) Provides exposure to broader skills and wider responsibilities. | (1) Competence erodes more rapidly as generalists can’t keep up with every development. (2) Specialist talent becomes harder to attract. (3) Innovation is restricted to existing areas. (4) Teams must compete for pooled resources | Improves the informal system in the short run at the cost to formal needs. |

| Matrix Model | (1) Provides maximum flexibility (2) Can shrink or expand with need (3) Can provide multiple career paths, rewarding both special and integrative skills. | (1) Two budget, two or more bosses, dual reward systems lead to conflicts. (2) People must invent or discover new procedures and norms. (3) Complicates relationship at every turn. | When managed well, it combines state-of-the-art expertise with focused efforts on each project. |

Diagnosing The Structure

An organization’s formal structure can be diagnosed using the following steps:

- Draw an organization chart showing the most significant units or functions.

- How does the chart look? Is it mainly functional? Product-based? or a mix of both? Or is it unclear at this stage?

- What is the rate of change the environment demands (High / Medium / Low)?

- Are individual units within the current structure responsive to that rate of change?

- Overall, does the structure fit with the environment? (Rate between excellent to poor)

- Was there a recent reorganization? If yes, what problem was the reorganization supposed to solve, and to what extent did it solve the problem?

Sometimes, work gets done through informal structures that form overtime to fill the gaps left by the formal structure. Ask the following questions to identify them:

- Are important organizational tasks “falling through the cracks,” i.e., they have no owners?

- How many such tasks exist? A few? Many? What are the reasons?

- To what extent are those without formal responsibility taking on tasks to keep things moving?

- Trace the units/persons managing significant environmental demands. Is their response adequate?

- Is there a relationship between the structure as it is and the degree of consumer and/or producer satisfaction? (Yes / No) If yes, what is the correlation?

3. Relationships

There are three important relations at play in any organization: (1) Relationships between people (e.g., peers or boss-subordinate), (2) Relationships between different units (groups) performing the tasks, and (3) People’s relation with technology (e.g., systems or equipment).

The six-box model focuses on the interactions and dynamics among individuals and groups within the organization. From a diagnosis standpoint, these are discussed in more detail:

Relationship Between People

Conflict between people can be detected by diagnosing the formal system for two possible dysfunctions: (1) People need to work together but do not do it well; (2) People don’t need to work together yet are forced into collaboration in the name of “good human relations” or because they “should.”

Relationship Between Units

To some extent, conflict between units is inevitable by design due to differing objectives and priorities. Each unit will have a unique view of how to perform work effectively. For instance, a production team might aim to optimize batch sizes to reduce costs, while a sales team might want to push for immediate production to boost revenue.

Good inter-unit relationships enable units to work together to achieve results. A relationship is “good” as long as it advances the organization’s purpose and enhances (or doesn’t undermine) the self-esteem of the people involved.

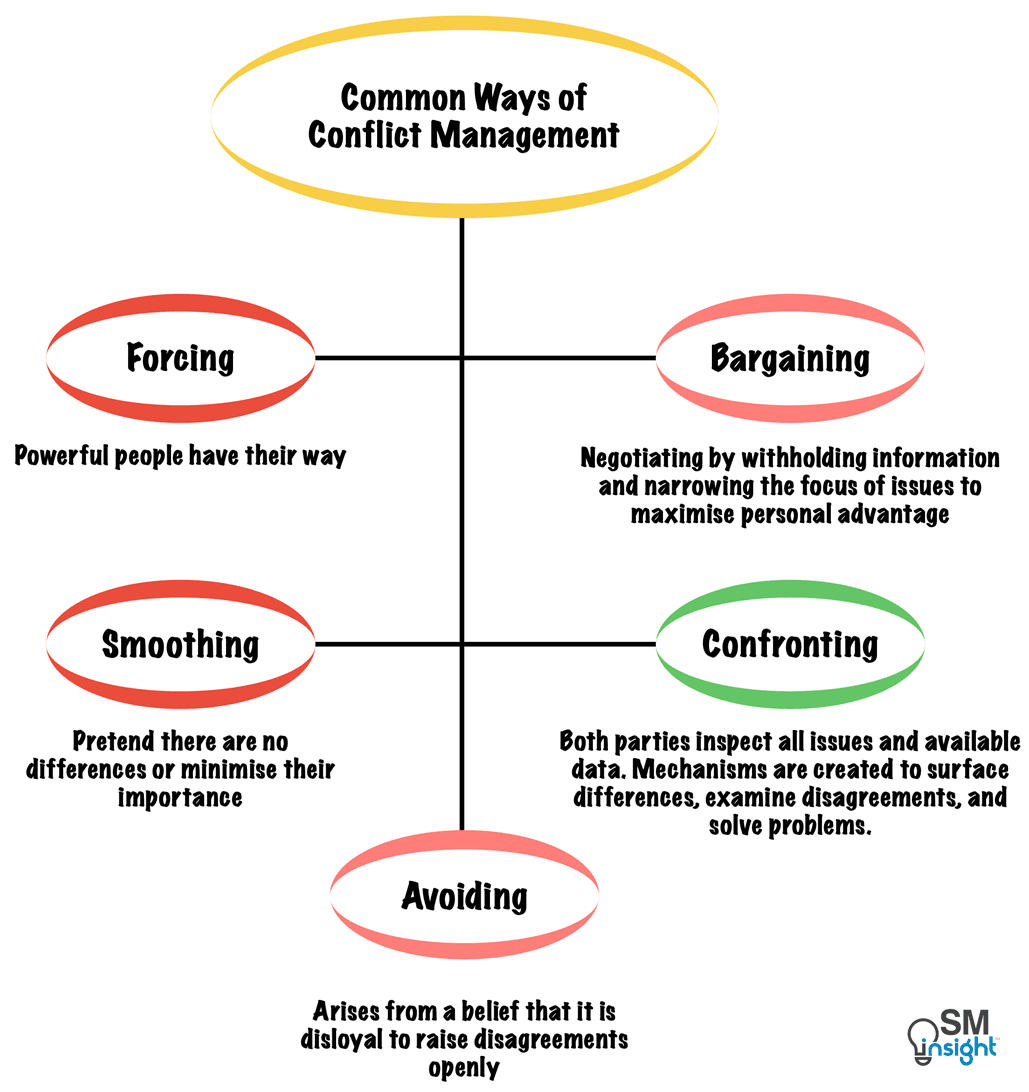

Common Ways of Conflict Management

Dealing with relations involves managing conflicts, which are both legitimate and inevitable. How they are managed makes the difference between high and low performance.

There are five ways in which people deal with conflicts:

In the worst-case scenario, organizations continue to operate by smoothing or avoiding differences amidst strained relationships and high interdependence. Common signs of poor conflict resolution mechanisms include:

- No one is charged with responsibility for managing the conflict.

- There is no integrator – a person accountable for getting units to resolve differences.

- The integrator lacks the knowledge or skills needed to manage conflicts effectively.

- No mechanisms or formally accepted processes exist to be used dependably for coordination.

While an integrator can address the above issues, this role is challenging and requires delicate skills. People tend to accept integrators for their competence and knowledge rather than authority. They must not be seen as taking one side. It is also important that the integrator’s rewards are tied to the total performance of the system, not just individual work.

Diagnosing Relationships

When diagnosing relationships, Marvin suggests beginning with a small group, such as three units performing independent tasks or three individuals within a work team. This helps focus the analysis and establish a clear understanding of key dynamics.

To carry out the diagnosis effectively, follow these steps:

- Name the chosen units, functions, and people (e.g., production, marketing, and design).

- Identify their interdependence – to what extent do they need to work together to satisfy consumers and/or environmental demands?

- Rate the dependency as high/medium/low, where high means each depends on the other for survival, medium means each needs some things from the other, and low means they can function without each other.

- Rate how well the units/people get along. This can range from excellent (where full cooperation is evident) to worst (where serious problems go unsolved).

- Observe how a pair having high or medium interdependence manages conflict or the lack of it.

- Are there structural differences, poor interpersonal skills, a combination of both, or an absence of a coordinating person/mechanism?

- To what extent does conflict hurt performance? How are they resolved?

- Use the matrix, as shown in the example below, to analyze how conflicts are managed. Rank the conflict management modes from 1 to 5, based on how often each is used between units/people. 1 = The mode is used very often. 5 = Least used:

| Unit 1 (Or person 1) | Unit 2 (Or person 2) | Unit 3 (Or person 3) | |

| Forcing | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Smoothing | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| Avoiding | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Bargaining | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Confronting | 4 | 3 | 3 |

- Are the top two (Rank 1 and 2) conflict management modes appropriate for each unit pair? If not, what are the reasons, and how can they be addressed?

4. Rewards

The purpose of a sound reward system is to motivate. Organizations often use salary and fringe benefits as motivators. While effective, these only work until people’s basic needs are met.

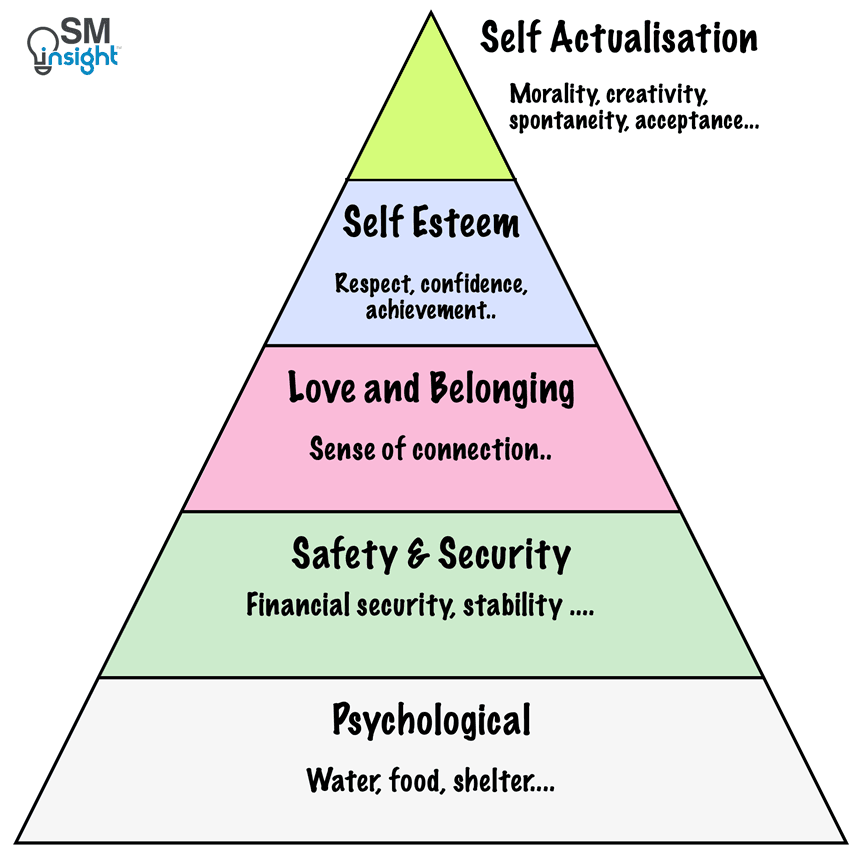

The effectiveness of rewards is best explained by Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which categorizes human needs into five levels:

Salary and fringe benefits primarily address the lower levels of the hierarchy, which are physiological and tied to basic survival (needs like food and shelter) and safety (financial security and stability).

Once these needs are met, individuals naturally focus on higher-level needs such as social belonging, esteem (recognition and achievement), and self-actualization (personal growth and fulfillment). Factors such as meaningful work, personal development, and recognition become more important in driving motivation.

Hence, the key is to turn reward theory into effective organizational practices where people see rewards as symbols of worthy work that the organization needs and values (recognition).

Another important factor is equity (fairness). People’s actions often depend on their perception of fairness, regardless of the actual benefits or compensation they receive. Informal feelings or beliefs about fairness can override formal reward systems, affecting alignment with organizational goals.

For example, in 2013, Microsoft had to abandon its controversial stack-ranking system, which required each business unit to rank a certain percentage of employees as top performers, average performers, or poorly performing [7].

Diagnosing Reward Effectiveness

Before diagnosing an organizational reward system, it is essential to clarify three key questions regarding its design:

- What does the organization need to achieve? (objectives – environment alignment)

- What behaviors or outcomes are rewarded, both explicitly and implicitly? (the formal reward system)

- What do employees perceive as being rewarded or punished? (the informal system and its psychological impact)

Then, the existing system (both formal and informal) can be measured against Maslow’s hierarchy by asking the following questions:

- What exists now that fulfills each need?

- Are they enough to motivate?

- What are the major strengths and weaknesses of the current reward system?

- How can the gaps be addressed?

- If “cracks” were identified in the formal structure, are the people who address them identified and rewarded?

5. Leadership

Much of the leadership theory concerns the organization’s informal system, where individual behavior can range from autocratic (System 1) to democratic (System 4). This is best explained using Rensis Likert’s four main styles of management as shown [8]:

| System | Trust | Motivation | Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| System 1 | No trust | Fear, threats, and punishment | Little interaction, always distrust |

| System 2 | Master/Servant | Rewards and punishment | Little interaction, always caution |

| System 3 | Substantial but incomplete trust | Rewards, punishment, some involvement | Moderate interaction, some trust |

| System 4 | Complete trust | Goals based on participation and improvements | Extensive interaction. Friendly, high trust. |

The best managers are those who can emphasize production and/or people as the situation requires. This requires a combination of democratic and autocratic styles. Thus, managers can benefit by learning from each other’s approaches.

For example, democratic leaders can learn to stop asking for answers when they know what to do and be more decisive, while autocrats can learn to collect more data before plunging ahead.

Because changing one’s leadership orientation is difficult, rather than training for change, organizations must first consider (1) fitting leaders to the task/situation and (2) changing the task to fit the leader’s style.

When scanning the leadership box of the Six Box Model, it must be checked if leaders perform the following four tasks:

- Do they define a clear purpose for their team/unit?

- Are defined purposes embodied in programs?

- Are those purposes defended in times of conflict?

- Are leaders able to manage internal conflict?

Leaders must also take responsibility and initiative for scanning the six boxes, looking for formal and informal problems, and acting on them. While this task can be shared, it cannot be delegated. This becomes more important in functional organizations where specialists have a narrow focus and are not expected to be responsible for the entire organization.

The main leadership challenge is persuading others to share the risk, which is difficult to achieve unless a leader has a promising vision and can inspire. This requires a combination of behavioral skills, an understanding of the environment, and a will to focus on purpose, especially when a problem exists in one of the six boxes.

Diagnosing Leadership

The following questions help in diagnosing leadership effectiveness:

- How can the informal behavior of the organization be characterized? Are most people task-oriented, relationship-oriented, or both?

- How appropriate is the behavior in the context of the organization’s defined purpose?

- What leadership style does the top management follow? What about the topmost leader?

- What are some strengths and weaknesses of the current leadership style?

- To what extent does leadership make a formal effort to monitor and balance the (six) boxes? What effect does this have on the organization?

- To what extent does the leader or leadership group’s informal behavior relate to the formal systems and procedures? What are the consequences?

6. Helpful Mechanisms

These are organizational mechanisms designed to facilitate concerted efforts and guide people in performing work. Procedures, policies, meetings, systems, committees, bulletin boards, memos, reports, and information are all examples of mechanisms.

Mechanisms are helpful when they:

- Assist in coordinating or integrating work, helping people do things together that require joint efforts.

- Assist in monitoring the organization’s work, helping people track whether things are going well.

- Help deal with issues in the other five boxes for which existing procedures are inadequate.

Helpful mechanisms align with organizational goals, reduce friction, and enhance productivity, while bad mechanisms hinder processes, create bottlenecks, and contribute to frustration. The table below provides examples of helpful and hindering mechanisms:

| Category | Good Examples | Bad Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Communication Channels | Easy-to-use tools such as Slack for effective communication. Regular cross-departmental meetings to avoid silos. | Over-reliance on informal communication leading to inconsistency. Overlapping responsibilities, no clarity on reporting channels. |

| Decision-Making Frameworks | Clear escalation protocols for resolving issues. Well-documented and accessible SOPs. | Bureaucratic procedures causing delays in decision-making. Overcomplicated workflows that confuse employees. |

| Knowledge Management | Centralized repositories for policies and guidelines. Training programs for employee upskilling. | No formal system for knowledge-sharing, resulting in information silos. Lack of training materials or outdated resources. |

| Technology & Tools | Use of CRM systems to streamline customer management. Automated ERP systems for efficient resource planning. | Outdated/redundant software that doesn’t integrate with other systems. Tools with poor user interface, leading to low adoption. |

| Conflict Resolution Mechanisms | Neutral mediators for dispute resolution. Policies encouraging transparency and fairness in grievance handling. | Escalating every conflict leading to wasted management time. |

| Feedback Loops | Systems for capturing and acting on employee/customer feedback. Regular follow-ups on issues to ensure resolution. | Ignoring collected feedback. Inconsistent follow-ups on reported issues, leading to unresolved problems. |

Helpful mechanisms can be classified into three categories:

- Formal—includes policies, procedures, agendas, meetings—formal events, activities, and tools that have been found to help people work together.

- Informal—ad hoc solutions, devices, inventions, and creative adaptations that people devise spontaneously to solve problems not envisioned by formal mechanisms.

- Traditional management systems—planning, budgeting, control, and measurement (information). Helpful mechanisms must exist in each of these four areas.

Organizations must continually revise their mechanisms, eliminate existing ones, and add new ones as needed. This deliberate creation of new mechanisms is essential for identifying and closing gaps between “what is” and “what ought to be.”

Diagnosing Helpful Mechanisms

Start by asking the following questions:

- Identify examples of mechanisms that are genuinely helping people in working together in the organization. List both formal and informal examples.

- Identify some unhelpful formal and informal mechanisms. What makes them unhelpful?

- Are there identified problems in other boxes that result from unhelpful mechanisms?

- What new mechanisms can be created that could improve the situation? Both formal and informal, simple and complex?

- Which of the new mechanisms is most doable?

Using Six Box Model as a Diagnostic Tool

The six-box framework is an early warning system to guide decisions on whether and where corrective actions are needed. It offers a three-tiered diagnostic approach to evaluate an organization’s:

- Environment fit: does the organization align with its external environment?

- Structural alignment: is the organizational structure designed to fulfill its purpose effectively?

- Alignment of norms and intent: are the organizational norms, including formal systems and informal practices, consistent with their intended purpose?

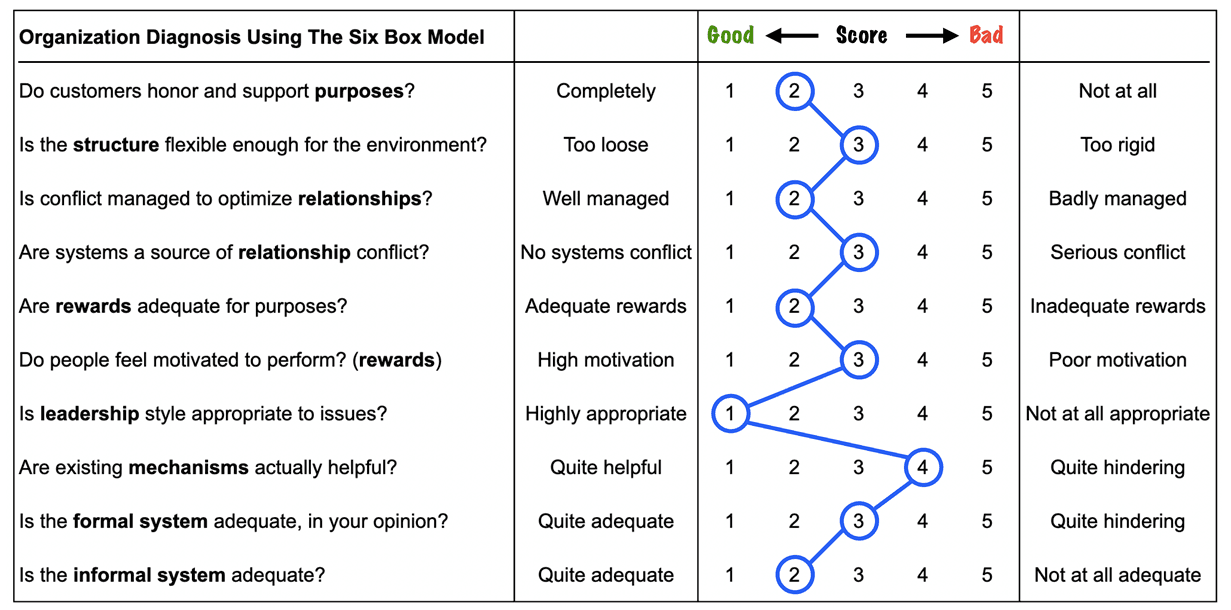

Below is a 10-point questionnaire based on the six-box model, which leaders can use for organizational diagnosis. Drawing a straight line from circle to circle provides a helpful way of understanding an organization’s health. More circles to the left indicate a healthy situation, while more to the right points to difficulties:

Thus, the six-box model is an effective framework for asking diagnostic questions about each box, yielding useful data and allowing leaders to take corrective actions.

References

1. “Rethinking organizational health for the new world of work.” McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/rethinking-organizational-health-for-the-new-world-of-work. Accessed 30 May 2025.

2. “About Marvin”. Marvin Weisbord, http://www.marvinweisbord.com/index.php/about/. Accessed 24 May 2025.

3. “Organizational Diagnosis: A Workbook Of Theory And Practice”. M. R. Weisbord, https://www.amazon.com/Organizational-Diagnosis-Workbook-Theory-Practice/dp/0201083574. Accessed 25 May 2025.

4. “Organizational Diagnosis: Six Places to Look for Trouble with or Without a Theory.”. Weisbord, M.R., https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/105960117600100405. Accessed 24 May 2025.

5. “The application of a diagnostic model and surveys in organizational development.” Peter Lok and John D Crawford, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235295127_The_application_of_a_diagnostic_model_and_surveys_in_organizational_development. Accessed 30 May 2025.

6. “A Theory of Human Motivation A. H. Maslow (1943)”. Classics in the History of Psychology, https://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm. Accessed 28 May 2025.

7. “Microsoft axes its controversial employee-ranking system.” The Verge, https://www.theverge.com/2013/11/12/5094864/microsoft-kills-stack-ranking-internal-structure. Accessed 30 May 2025.

8. “Rensis Likert”. Strategies for managing change, https://www.strategies-for-managing-change.com/rensis-likert.html. Accessed 28 May 2025.