In every organization, there exist areas where instructions are vague, authority is fuzzy, budgets are nonexistent, and strategy is unclear. These are often the areas (or “white spaces”) where the greatest opportunities for performance gains lie.

Rummler and Brache’s Nine Boxes Model is a performance improvement tool that helps organizations identify and address such areas.

It provides a framework for understanding and managing the three levels of performance (organization, process, and job/performer) and the three performance needs (goals, design, and management) to achieve desired outcomes.

The model was developed by Geary Rummler and Alan Brache and first introduced in 1990 as part of their work on improving organizational performance [1].

Limitations of a vertical (hierarchical) view

Many executives don’t fully understand their businesses. They may know their products, services, customers, and competition well. However, they often lack an understanding, at a sufficient level of detail, of how their business develops, makes, sells, and distributes products/services.

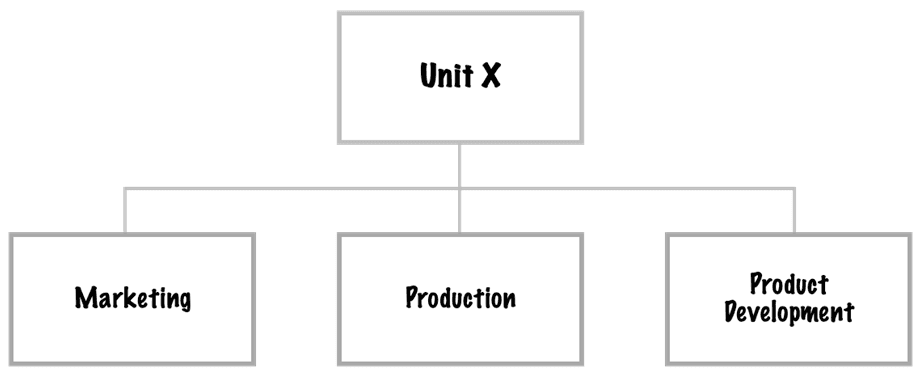

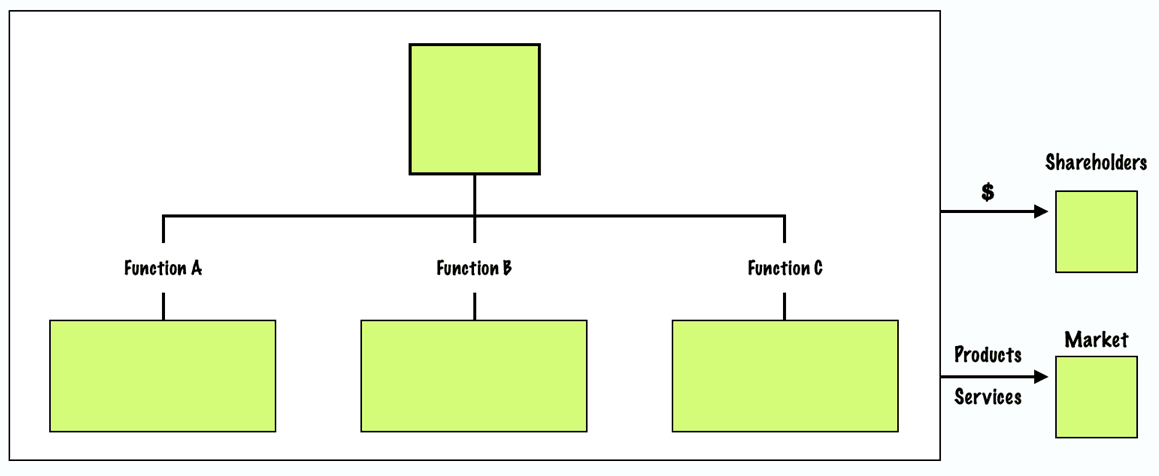

When asked to represent their business on a piece of paper, be it a whole company, a business unit, or a department, most resort to the traditional organizational chart:

While this chart is a valuable administrative convenience, it misses several crucial aspects. It does not show the business’s customers, products and services, or the workflows used to develop, produce, and deliver them.

In short, it does not help us understand what the organization does, whom it does it for, or how it does it.

This is not an issue in small or new organizations, where everyone knows each other and is required to understand other functions. However, as the organization grows, its environment changes, and technology becomes more complicated. This is when the vertical view presented by the traditional organizational chart becomes a liability.

When managers see their organizations vertically and functionally, they manage them that way. Goals are established in isolation, leading subordinate managers to see other functions as rivals rather than allies in their fight against the competition.

A silo culture sets in, forcing managers to resolve lower-level issues while taking away time from higher-priority customer and competitor concerns. Departments tend to excel at their level while hurting the organization as a whole.

The horizontal view of an organization

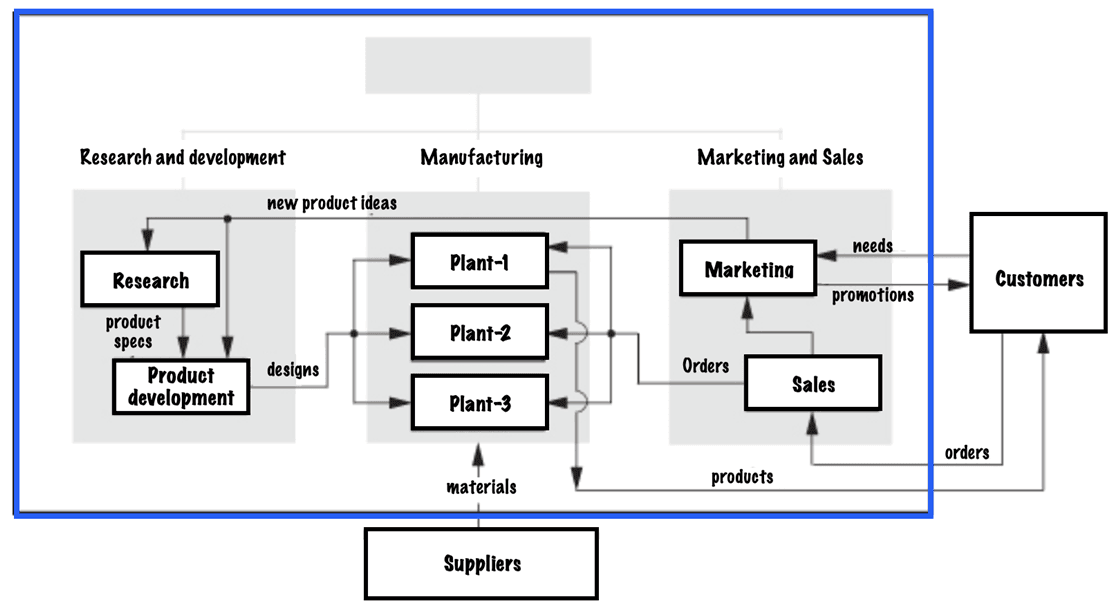

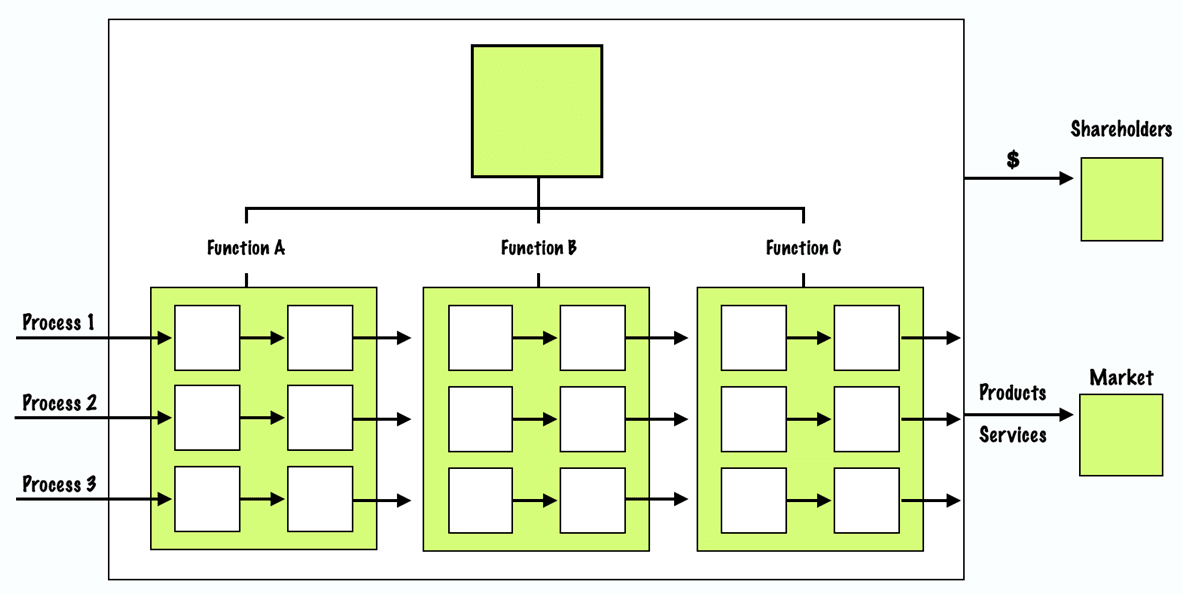

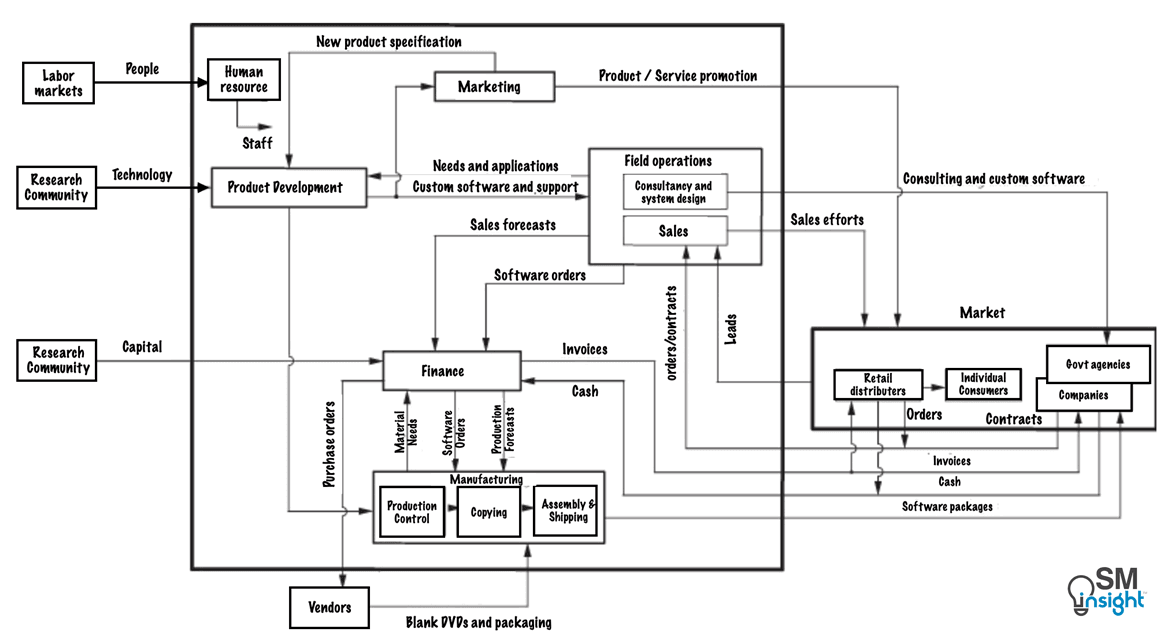

To understand the “what,” “why,” and “how” of an organization, a horizontal or system-based view is necessary:

This high-level picture of a business includes the three missing components – the customer, the product, and the flow of work while showing how work gets done and the processes that cut across functional boundaries.

Organizations behave as adaptive systems, processing and converting input resources to products and services according to market needs while providing financial value to shareholders. They are also affected by competitors and the social, economic, and political environment.

Because everything internal and external to an organization is connected, the greatest improvement opportunities lie at the functional interfaces—the points at which information or products pass from one department/function to another.

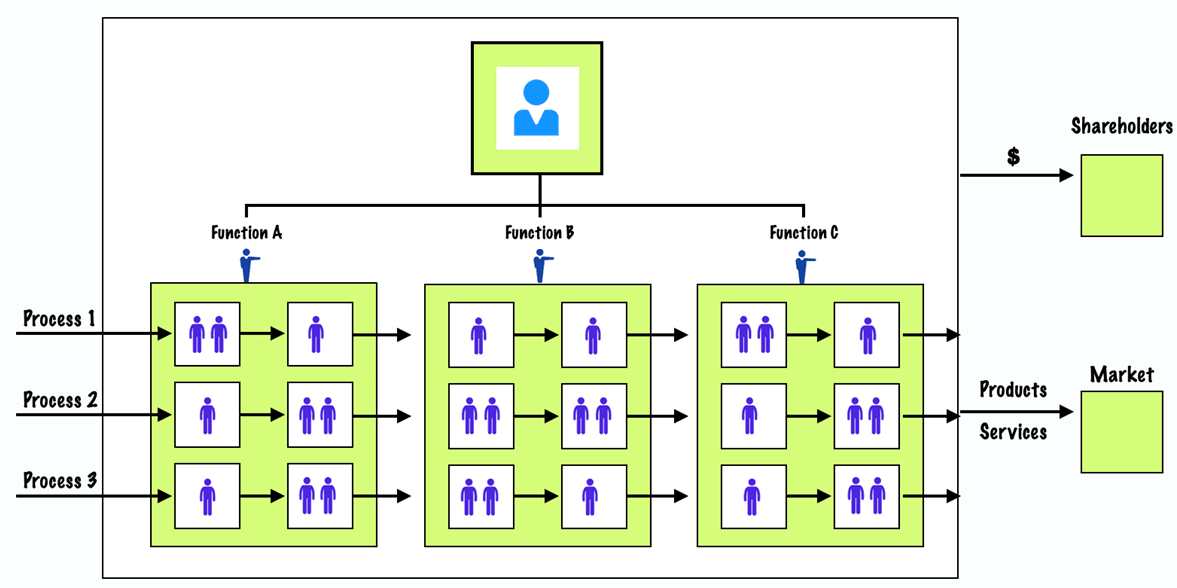

Three levels of performance

When organizations are viewed horizontally, their performance can be understood on three levels (shown below). These three levels represent the anatomy of performance. They are critical and interdependent, and failure in any of them affects the organization’s ability to perform effectively.

The organization level

The organization level emphasizes an organization’s relationship with its market and the basic “skeleton” of its major functions. This is “Level-I” performance, where the variables include strategies, organization-wide goals and measures, organization structure, and resource deployment.

The process level

Organizations produce output through cross-functional processes that must meet customer needs and work effectively and efficiently. An organization is only as good as its processes.

While the organization level provides a perspective, sets a direction, and points to areas of threat and opportunity, the process level is where substantive change usually needs to take place.

Even a clear strategy, logical reporting relationships (Organization), and skilled, reinforced people (job/performer) cannot compensate for flawed business and management processes.

The people level

Individuals perform and/or manage processes. At this level, performance variables must be managed, including hiring and promotion, job responsibilities and standards, feedback, rewards, and training.

The three Performance Factors

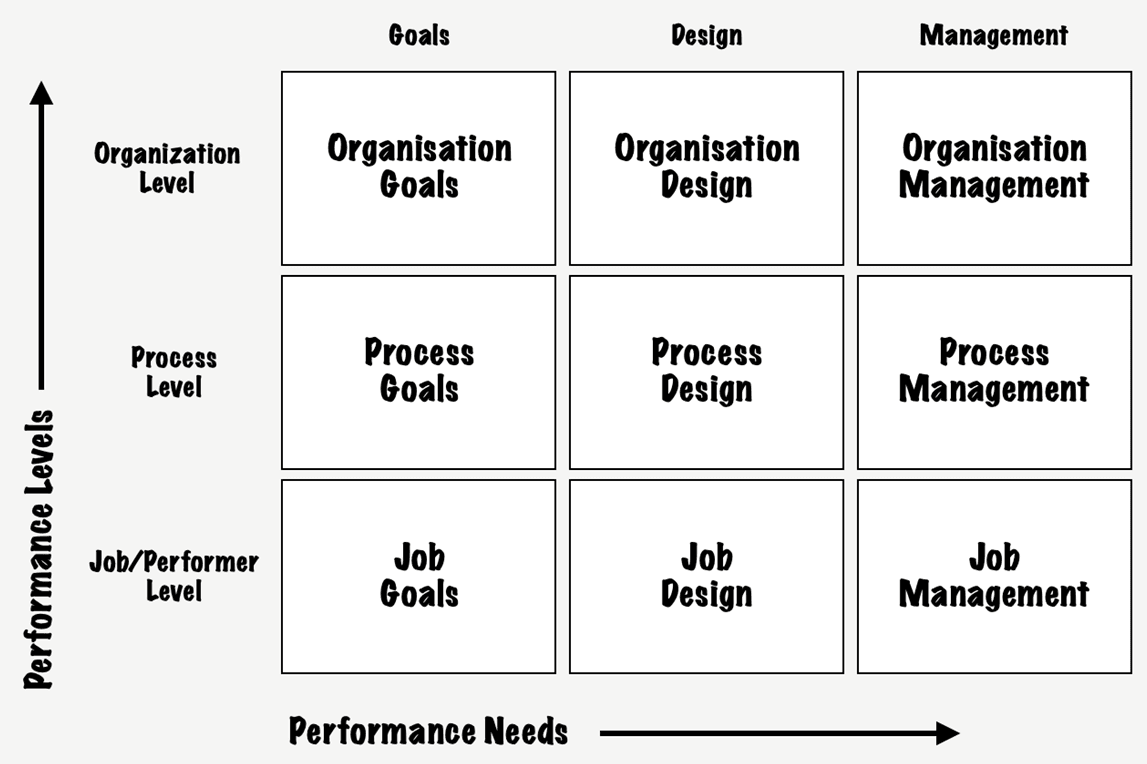

The organization, process, and people levels constitute just one performance dimension. Overall performance (how well an organization meets customers’ expectations) results from its goals, structures (design), and management actions across these three levels.

These factors, also known as performance needs, form the second dimension. They determine the effectiveness at each level and the effectiveness of the systems within them:

- Goals—the organization, process, and job/performer levels each need specific standards that reflect customers’ expectations for product and service quality, quantity, timeliness, and cost.

- Design—the organization’s structure, process, and job/performer levels must include the necessary components and be configured to enable the goals to be met efficiently.

- Management—each of the three levels requires management practices that ensure the goals are current and are being achieved.

Rummler and Brache’s nine box model

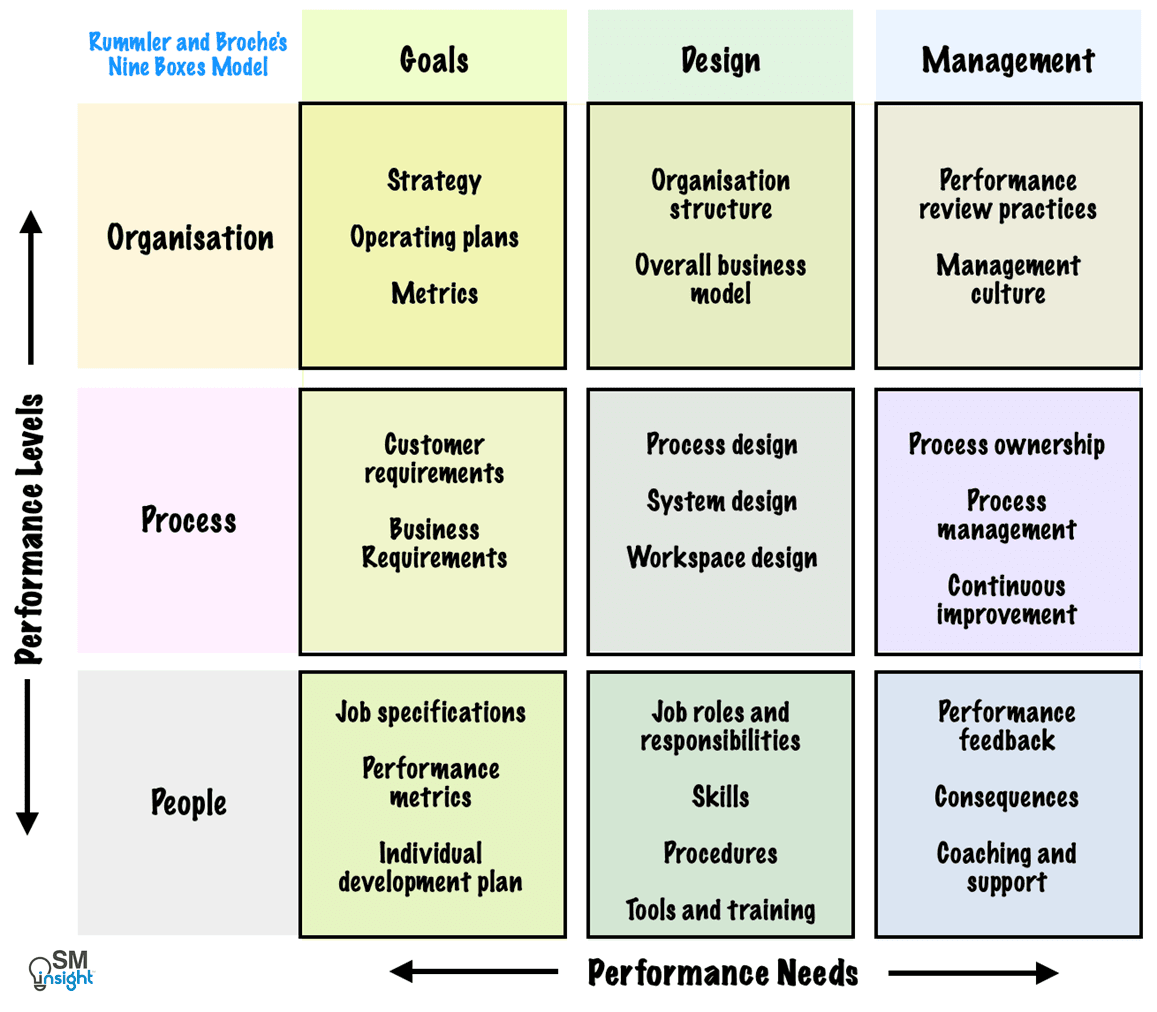

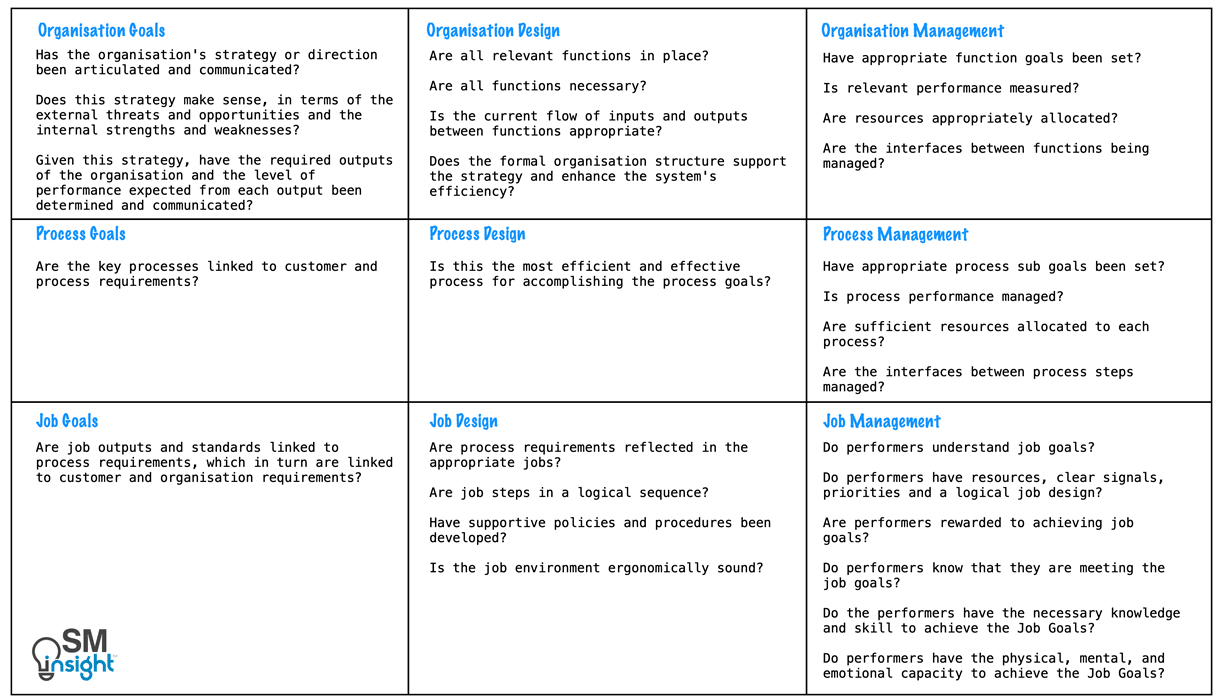

Combining the three performance levels with the three performance factors results in nine variables—a comprehensive set of improvement levers that can be used by managers at any level.

These nine variables, arranged in a 3×3 matrix, are known as the Rummler and Brache’s nine-box model.

Effective performance management requires goal setting, designing, and managing across each of the three levels of performance which are interdependent. This model can also be used to gain insights into the shortcomings of failed attempts to change and improve organizations.

For example, attempts to improve organization and process performance through training alone would fail because it only addresses one dimension (the job/performer). Likewise, attempts to improve a process through automation rarely realize their true potential if they are not linked to organizational goals and people’s needs.

Practical Applications

Rummler and Brache’s nine-box model can be used in various scenarios as:

- A tool for diagnosing and eliminating deficient performance (for example, cycle time in manufacturing or loss of margins in a retail chain).

- An engine for continuously improving systems that are performing adequately (for example, how an airline responds to needs for unique aircraft configurations).

- A road map for guiding an organization in a new direction (for example, toward entering the software business or selling in a new business environment).

- A blueprint for designing a new entity (for example, a factory of the future or a marketing department).

It can be used across various organizational levels, including executives providing the vision, leadership, and impetus for change, managers implementing companywide changes, and analysts designing the systems and procedures.

Using the nine-box model

Rummler and Brache’s nine-box model forces organizations to examine goals, design, and management across three levels: organization, process, and performer.

Understanding and Managing the Organization Level

Organization Goals

At the organizational level, goals are strategic. A good strategy must identify the organization’s products and services, customer groups (markets), competitive advantage(s), product and market priorities (emphasis areas)

An effective set of organizational goals should include:

- Values of the organization.

- Customers’ requirements.

- Financial and nonfinancial expectations.

- Targets for each product family and market.

- Expectations for each competitive advantage to be established or enhanced.

Good organizational goals should be based on the critical success factors for the company’s industry and must be derived from competitive and environmental scanning information (such as benchmarking). They must be quantifiable whenever possible and clear to those who must understand and be guided by them.

The most important questions to be asked when setting organizational goals are:

- Has the organization’s strategy or direction been articulated and communicated?

- Does this strategy make sense in terms of external threats and opportunities and internal strengths and weaknesses?

- Given this strategy, have the required organizational outputs and the level of performance expected from each output been determined and communicated?

It is also important that these goals be continually evaluated and reset to fit changing requirements and capabilities. Without this, goal achievement leads to complacency, which serves as a barrier to continuous improvement.

Organization Design

Managers and analysts must design an organization that enables the goals to be met. One way to check if the organization supports the achievement of the organization’s goals is to develop a relationship map [2].

A relationship map depicts the customer-supplier relationships among the business’s line and staff functions. It shows the inputs and outputs that flow among functions while revealing the “white space” between the boxes on the organizational chart. Relationship maps help:

- Understand how work currently gets done (how the organization behaves as a system).

- Identifies the disconnects in the organization’s wiring (missing, unneeded, confusing, or misdirected inputs or outputs).

- Develop functional relationships that eliminate disconnects.

- Evaluate alternative ways to group people and establish reporting hierarchies.

Therefore, the first step in organization design is to examine and improve the input-output relationships among functions. The most important questions to be asked here are:

- Are all relevant functions in place?

- Are these functions necessary?

- Is the current flow of inputs and outputs between functions appropriate?

- Does the formal organization structure support the strategy and enhance the system’s efficiency?

After identifying the disconnects, an organization must seek to eliminate them.

Organization Management

Managing an organization by taking a system-based view includes four dimensions:

- Goal Management: Subgoals across every function must align and support the organizational goals. This is important to avoid functional silos that optimize locally but become detrimental to the organization’s growth.

- For example, a product development department’s goal must ensure that its new products and services are driven by market needs and not by technical wizardry.

- Performance management: To achieve goals, performance must be managed at an organizational level. This includes obtaining regular feedback, setting up cross-functional problem-solving teams, measuring performance in terms of goals, and reestablishing goals to fit the current reality.

- Resource Management: Resource needs such as people and dollars must be allocated judiciously and aligned with organizational goals. Ad hoc measures such as manpower reduction for cost-cutting can prove costly if they compromise the resources required for reaching organizational goals.

- Interface Management: key barriers to and opportunities for organizational goal achievement reside in the “white space” between functions. These areas need particular attention.

For example, a product introduction goal will only be achieved if the product development and product introduction system (which includes marketing, product development, and field operations) work well.

Key questions to ask in organization management are:

- Have appropriate functional goals been set?

- Is relevant performance measured?

- Are resources appropriately allocated?

- Are the interfaces between functions being managed?

Understanding and Managing The Process Level

Between every input and output is a process, a series of steps designed to produce a product or service. While some may be contained wholly within a function, most are cross-functional, spanning the “white space” between the boxes on the organization chart.

There are three kinds of processes:

- Primary processes: those that result in a product or service that is received by an organization’s external customer (manufacturing, distribution, billing, customer service, etc.)

- Support processes: those that produce products that are invisible to the external customer but essential for effective business management (budgeting, recruiting, training, purchasing, etc.)

- Management processes: These include actions managers should take to support the business (strategic planning, goal setting, performance management, etc.)

A process is like a “value chain,” where each step adds value to the preceding steps. For example, the prototype market testing process adds value by ensuring the product is appealing to the market before the design is finalized.

Processes are also consumers of resources. They need to be assessed in terms of the value they add and the capital, people, time, equipment, and material required to produce that value.

Effective and logically designed processes are important because an organization is only as effective as its processes. In the long run, no amount of skill can compensate for weak processes or fundamentally flawed processes.

Process goals

Every primary and support process contributes to one or more organizational goals. Thus, they should be measured against process goals that reflect their contribution.

While functions and departments have goals, processes rarely do because they cross functional boundaries. For example, the billing processes may rarely have a goal, but the billing department will likely have one.

There are three sources of process goals: organization goals, customer requirements, and benchmarking information. Process benchmarking, which compares a process to the same process in an exemplary organization, is particularly useful.

When establishing process goals, the main question is whether the goals for key processes are aligned with customer and organizational requirements.

Process design

Once the process goals are established, managers must ensure the processes are designed to achieve those goals efficiently.

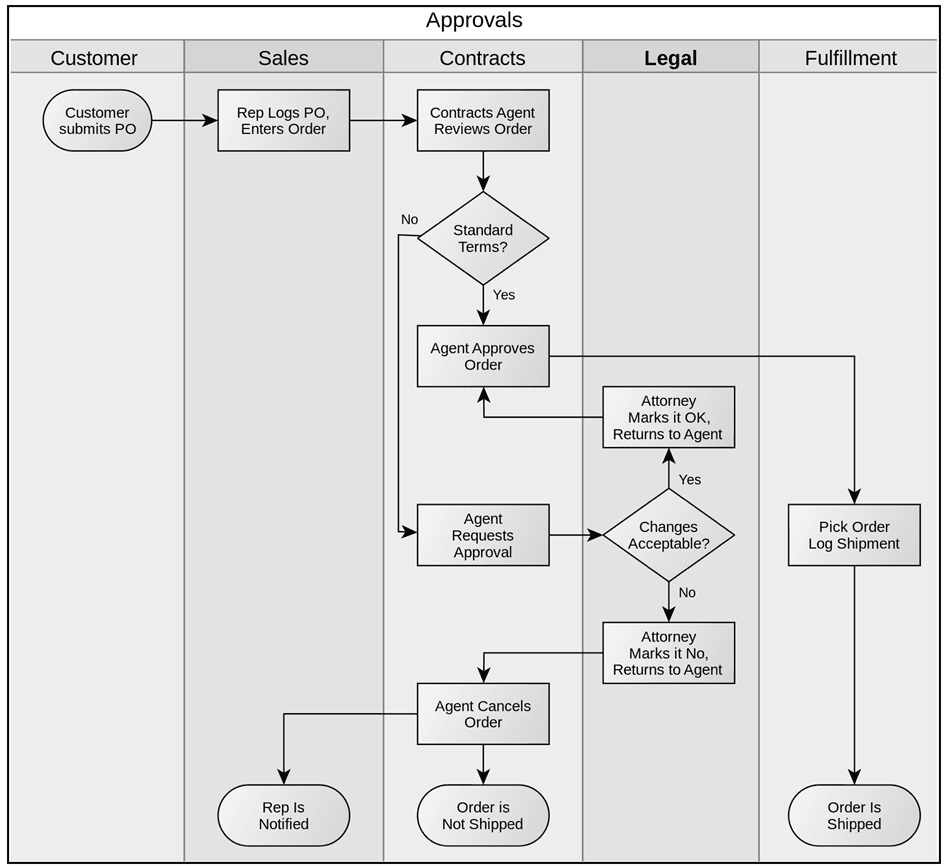

An effective way to determine whether each process and its subprocesses are appropriately structured is to have a cross-functional team build a process map [3] that displays how work gets done.

While a relationship map shows the input-output relationships among departments, a process map documents, in sequence, the steps that departments go through to convert inputs to outputs for a specific process.

All too often, teams realize that there isn’t an established process; the work just somehow gets done.

The most important question in process design is: “Is this the most efficient and effective process for achieving the process goals?”

Process management

Even the most logical, goal-directed processes don’t manage themselves. They require four levels of management:

- Goal Management: Based on the overall process goals, sub-goals should be established throughout the process. For example, an order completion process in sales could have sub-goals such as “100% completion within 24 hrs. of order.”

Once process subgoals have been established, functional goals must be developed. Because a function’s purpose is to support processes, functional goals should be measured on the degree to which they serve processes. They must meet the needs of both internal and external customers. - Performance Management: Managers must establish systems for obtaining internal and external customer feedback on the process outputs. Process owners must be appointed to oversee the entire process.

To continuously improve processes, they must track process performance against the goals and subgoals, provide feedback on performance information to the functions that play a role, establish mechanisms to solve process problems and adjust goals to meet new customer requirements. - Resource Management: Allocation of resources is a major part of a manager’s responsibility. Process-focused resource allocation tends to differ from the usual function-oriented approach.

Process-driven resource allocation results from determining the dollars and people required for the process to achieve its goals. Once that is done, each function is allocated its share based on its contribution to the process. Each function’s budget becomes the sum of its portion of each process budget. - Interface Management: Processes comprise various functions where one provides a product or a service to another. Each of these points represents a customer-supplier interface that must be closely monitored to remove any barriers to effectiveness and efficiency.

To ensure proper attention, managers must establish and monitor measures that indicate the quality and efficiency of these interfaces.

In summary, the key questions to ask in process management are:

- Have appropriate process subgoals been set?

- Is process performance managed?

- Are sufficient resources allocated to each process?

- Are interfaces between process steps being managed?

Understanding and Managing The Performer Level

It is illogical to assume that people’s poor performance is at the root of all problems because people are only one part of the performance engine.

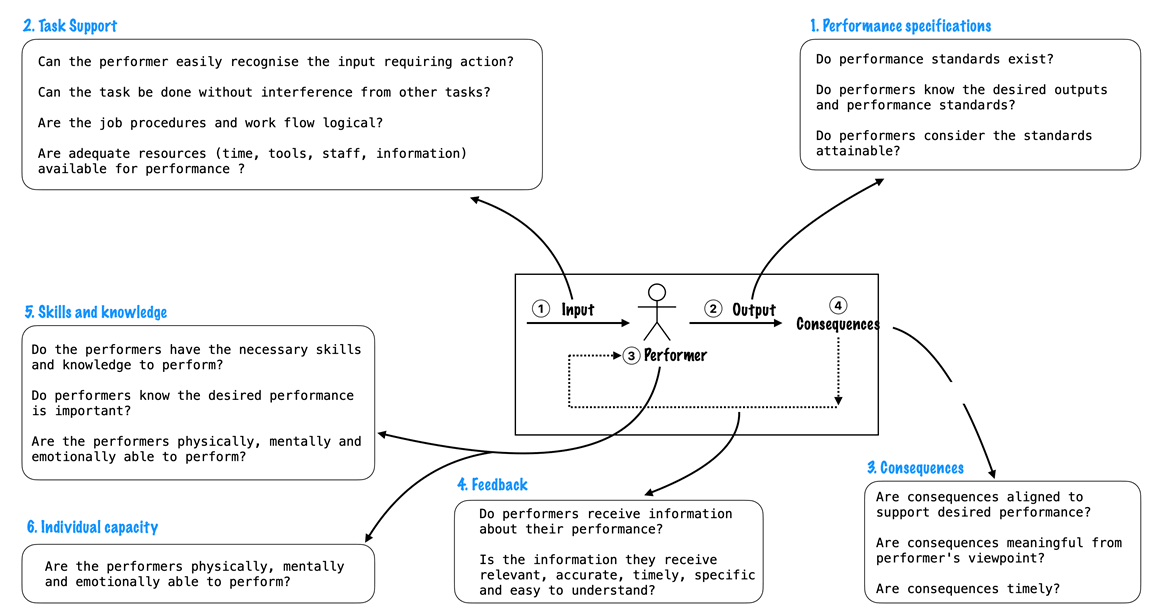

Authors Rummler and Brache used the concept of the Human Performance System (HPS), which has six variables that influence human performance.

The goals, design, and management at the organization and process levels are part of the system that affects human performance. HPS builds on these levels by providing a micro picture of people and their immediate environment. It reflects the input-process-output-feedback perspective that underpins the organization and process levels:

![The Human Performance System (Source: Improving Performance [1])](https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/wp-content/uploads/Human-Performance-System.png)

Inputs are the raw materials, forms, assignments, and customer requests that cause people to perform. They also include resources, systems, and procedures that represent the performers’ link to the process level.

Performers are the individuals or groups who convert inputs to outputs.

Outputs are the products/services the performers produce to contribute to the organization and process goals. People’s traits, skills, knowledge, and behaviors are all important performance variables.

Consequences are the positive and negative effects that performers experience when they produce an output. Positive consequences include bonuses, recognition, and more challenging work. Negative consequences include complaints and disciplinary action.

A consequence could be positive or negative, depending on the performer’s perspective.

Feedback is information that tells performers what and how well they are doing. It can come from error reports, statistical compilations, rejects, oral or written comments, surveys, and performance appraisals.

Thus, the overall output quality is a function of the quality of inputs, performers, consequences, and feedback.

Understanding and managing the job performer level requires systematic analysis and improvements across all five components.

If jobs are not designed to support process steps, and if job environments are not structured to enable people to make their maximum contributions to process effectiveness and efficiency, then organization and process goals will not be met.

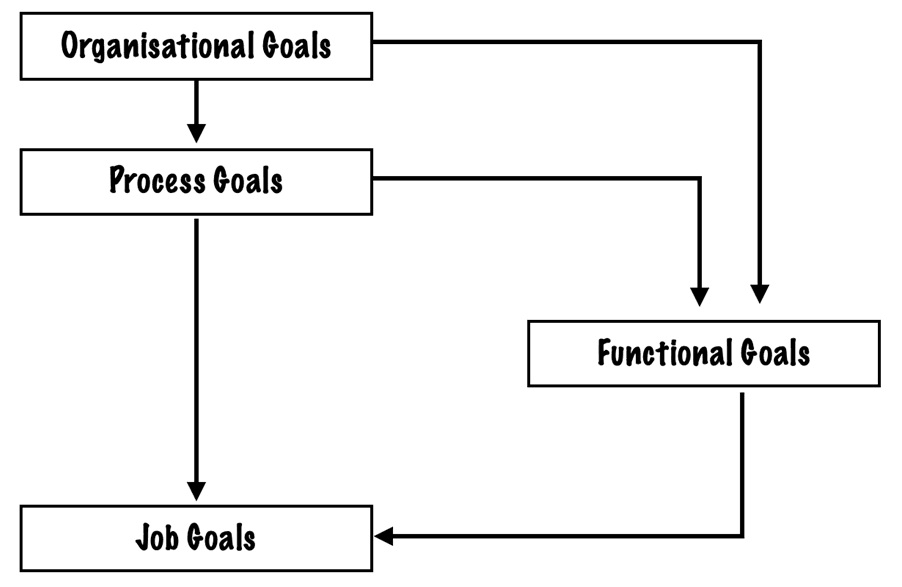

Job Goals

Because the role of people is to make processes work, their goals must reflect process contributions. The link between job goals and the goals at other levels is as shown:

The major distinction between this goal “flow-down” and traditional approaches is the process (rather than functional) orientation. While Job Goals should be directly linked to functional goals, both should be derived from the processes they support.

Goals must communicate to performers what they are expected to do and how well they are expected to do it. These two ingredients specify the output component of the HPS.

The key questions here are: Are job outputs and standards linked to process requirements? Are they, in turn, linked to customer and organization requirements?”

Job Design

Job design involves allocating responsibilities among jobs, determining the sequence of job activities, implementing job policies and procedures, and considering ergonomics.

Key questions to ask include:

- Are process requirements reflected in the appropriate jobs?

- Are job steps in a logical sequence?

- Have supportive policies and procedures been developed?

- Is the job environment ergonomically sound?

Job Management

Managing HPS’s five components at the job/performer level is crucial. There are a total of six factors that affect the effectiveness and efficiency of the HPS:

- Performance specifications: these are the outputs and standards that comprise the job goals. Managers must participatively establish process-driven job goals and take steps to ensure that all questions are answered.

- Task support: a well-structured job must contain easily recognized high-quality inputs, minimal interference, and logical procedures. Performers must also be supported with adequate resources to do the job. This factor is also addressed partially by job design.

- Consequences: because consequences are positive or negative effects that performers experience when they produce an output, they must support the efficient achievement of Job Goals.

For example, if an organization’s strategic goal is to sell a certain volume of new products, but sales commissions are linked to old products, the consequence is not aligned to support the desired performance.

Consequences must also be meaningful to the performer and occur quickly enough to provide an ongoing incentive. - Feedback: this tells the performer whether to change performance or to keep on performing the same. Without feedback, good performance can fall off track, and poor performance can remain unimproved.

- Skills and knowledge: If these are lacking, job performance is impaired. Skills include the official way of doing the job and hints and shortcuts that enable some performers to be exemplary.

- Individual capacity: no matter how supportive their environment or how effective their training is, performers will not be able to do their jobs if they lack the physical, mental, or emotional capacity to achieve the goals.

For example, a salesperson who cannot take rejection may have an individual capacity deficiency.

In summary, job management, at a high level, involves answering the following questions:

- Do the performers understand the Job Goals (the outputs they are expected to produce and the standards they are expected to meet)?

- Do the performers have sufficient resources, clear signals and priorities, and a logical Job Design?

- Are the performers rewarded for achieving the Job Goals?

- Do the performers know if they are meeting the Job Goals?

- Do the performers have the necessary skills and knowledge to achieve the Job Goals?

- If the performers were in an environment where the (above) five questions were answered as yes, would they have the physical, mental, and emotional capacity to achieve the Job Goals?

Nine Box Model and Organizational Strategy

Rummler and Brach’s nine-box model helps identify the questions that need to be answered for an organization’s strategy to guide the three performance levels effectively.

These nine performance variables, which stretch across the three dimensions of organization, process, and job/performer levels, must be addressed for effective strategy implementation.

Sources

1. “Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space on the Organization Chart.” Geary Rummler and Alan Brache, https://www.amazon.com/dp/1118143701 Accessed 17 Mar 2025.

2. “Function Relationship Map”. Rummler-Brache Group, https://www.rummlerbrache.com/function-relationship-map Accessed 16 Mar 2025.

3. “What is process mapping?”. IBM, https://www.ibm.com/topics/process-mapping Accessed 17 Jun 2024.

4. “Swimlane”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swimlane Accessed 17 Mar 2025.

5. “Rummler and Brache’s Nine Boxes Model.” HPT Manual, https://hptmanualaaly.weebly.com/rummlers-model.html Accessed 19 Mar 2025.

6. “Managing in the Whitespace.” Mark C. Maletz and Nitin Nohria (HBR), https://hbr.org/2001/02/managing-in-the-whitespace Accessed 19 Mar 2025.