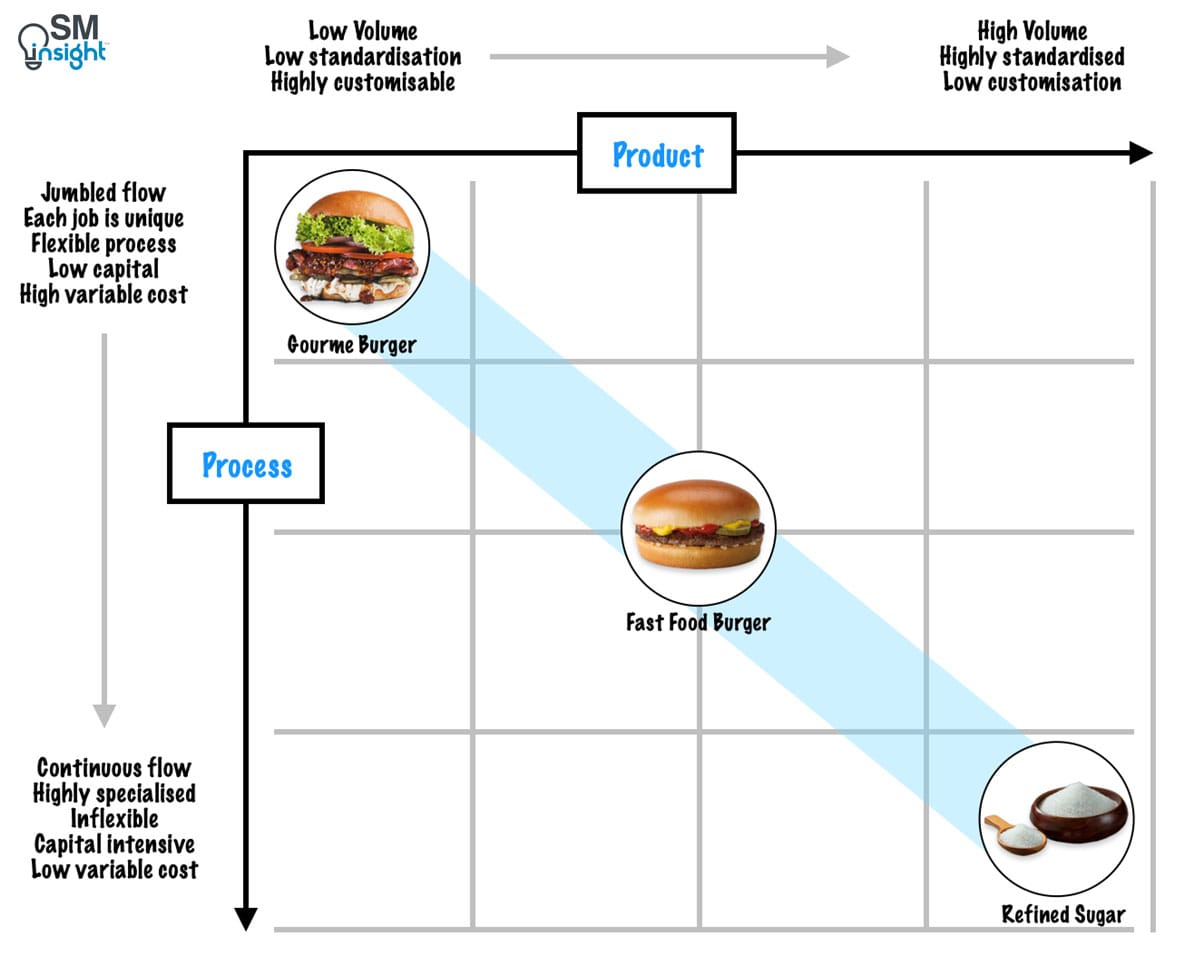

A fast-food joint typically offers a limited menu while relying on highly mechanized processes for quick service. In contrast, a gourmet restaurant focuses on bespoke, handmade dishes, taking time to customize to the customer’s liking and taste.

While the former may sell hundreds of dishes daily for cheap, the latter will only sell a few at a much higher price point.

Each of these operates differently because they occupy different positions in what is known as a product-process matrix.

What is the Product-Process Matrix

The Product-process matrix (PPM), also known as the Hayes-Wheelwright matrix, is a tool that analyzes the relationship between the product life-cycle stage and the process life-cycle stage:

PPM was developed by Robert Hayes and Steven Wheelwright and published in 1979 in the Harvard Business Review articles “Link Manufacturing Process and Product Life Cycles” [1] and “The Dynamics of Process-Product Life Cycles” [2].

By viewing the “product life cycle” and the “process life cycle” separately on two independent axes, the model helps companies better understand their strategic options, particularly from the point of their manufacturing functions.

The product process matrix explained

Just as a product and its market pass through a series of significant stages, so does the production process used to manufacture that product.

In the initial stages of the production life cycle, the process is typically “fluid” and highly flexible but not cost-efficient. As the process matures, it moves towards becoming increasingly standardized, mechanized, and automated, ultimately becoming highly efficient, capital-intensive, interrelated, and less flexible than the original fluid process.

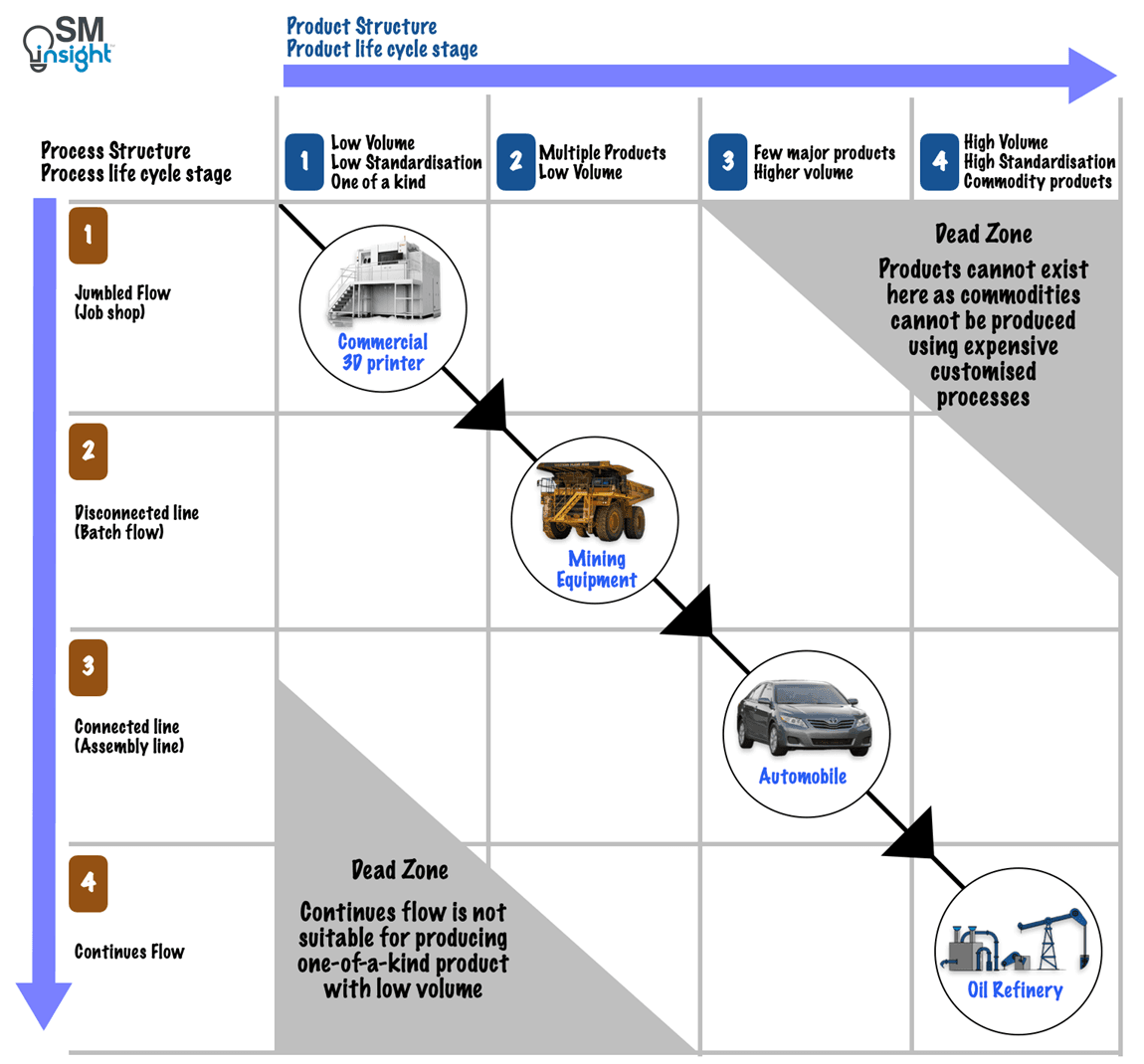

PPM uses a 4×4 matrix to represent the interaction of the product and the process life cycle stages.

The rows represent the major stages through which a production process tends to pass, going from the fluid form in the top row to the systemic form in the bottom row. The columns represent the product life cycle phases, going from great variety (highly customized) on the left-hand side to standardized commodity products on the right-hand side:

Moving along the diagonal

Any given company (or a business unit within it) can be characterized as occupying a particular region in the matrix, which is determined by the stage of the product life cycle and its choice of production process.

Typically, these positions are on (or close to) the diagonal of the matrix. Consider the examples shown in the PPM above.

One-of-a-kind jumbled flow

In the first example, the product is a commercial 3D printer where each job is unique, and a jumbled flow or job shop process is usually selected as most effective in meeting those product requirements.

From a manufacturing perspective, jobs arrive in different forms and require different tasks, and thus, the production equipment used tends to be relatively general purpose. For example, a robotic arm used to assemble parts of the 3D printer may also be reprogrammed to assemble some other product (a computer, for example).

Such production facilities are seldom used at 100% capacity, while workers typically have a wide range of production skills. Each job takes much longer to go through the plant than the labor hours required by that job.

Multiple products batch flow

Further down the diagonal, is an example of a mining equipment which usually follow a production structure characterized as a “disconnected line flow” process. Although the company may make several products, economies of scale in manufacturing usually lead such companies to offer several basic models with various options.

This enables manufacturing to move from a job shop to a flow pattern in which batches of a given model proceed irregularly through a series of workstations, or possibly even a low volume assembly line.

Higher volume assembly line

Even further down the diagonal are products like automobiles or home appliances, where only a few models are offered and use a relatively mechanized moving assembly line. The manufacturing process leverages economies of scale that arise from a standardized and automated process.

Production equipment used in an assembly line is customized for the specific product and less flexible than previous products. They also require more capital.

High-volume continuous flow

Down in the far right-hand corner of the matrix are heavily commoditized products such as oil or sugar. These are manufactured using highly automated continuous flow processes that are highly standardized, specialized, inflexible, and capital-intensive. Their disadvantages are more than offset by the low variable costs.

Consequences of moving off the diagonal

Straying too far from the diagonal is impractical due to a lack of economic logic (see dead zones indicated in the PPM above); however, some companies find an operating sweet spot a bit off the diagonal.

Rolls Royce, for example, has been manufacturing a limited product line of motorcars using a process that is more like a job shop than an assembly line.

Depending on the success in achieving focus and exploiting the advantages of niche, straying away from the diagonal can leave a company vulnerable to attack. This is because it also becomes difficult to coordinate marketing and manufacturing as the two areas confront increasingly different opportunities and pressures.

Advantages of using PPM

PPM helps address three key areas:

- Build distinctive competence.

- Understand the implications of selecting a product-process combination.

- Organize operating units to specialize in distinct portions of the manufacturing tasks.

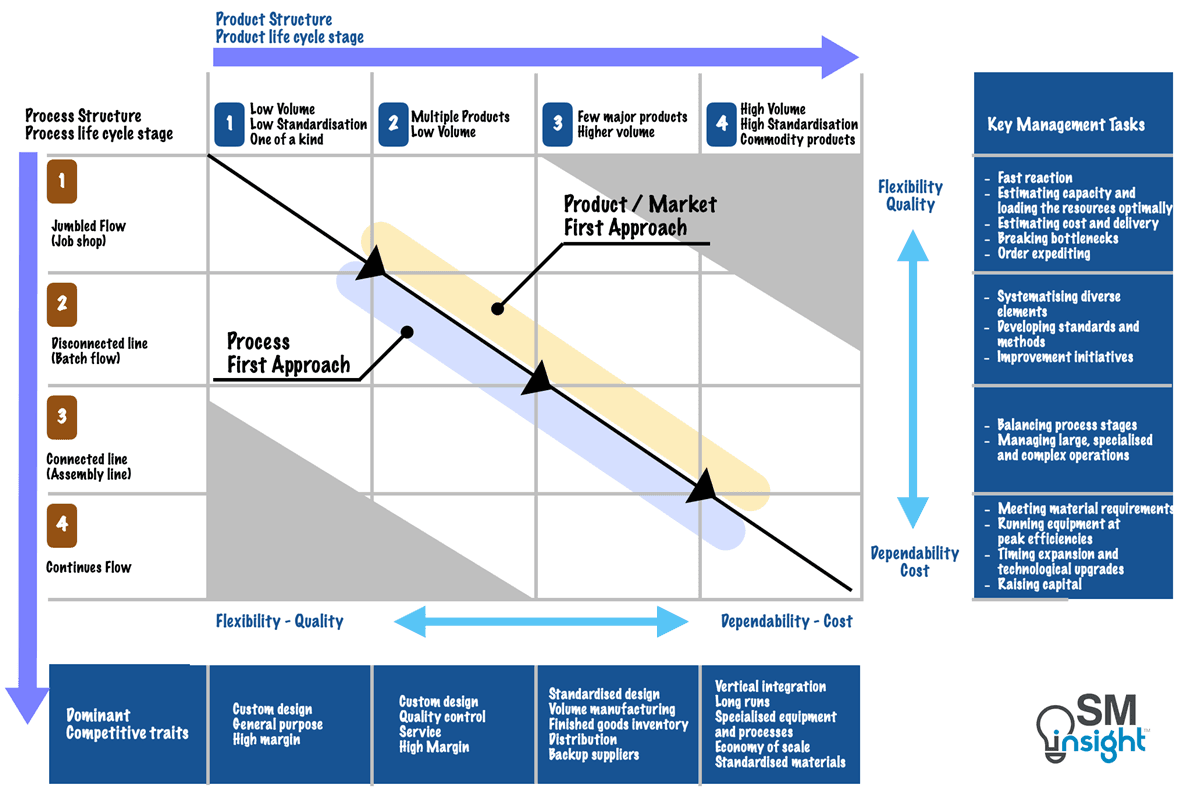

Building distinctive competence

Most companies want to be particularly good in certain areas while avoiding competition in others. They aim to guard this distinctive competence against outside attacks or internal aimlessness and exploit it where possible.

However, sometimes, management can become preoccupied with marketing concerns and lose sight of the value of manufacturing abilities. When this happens, strategy is shaped only by the product and market dimensions. In effect, management concentrates resources and planning efforts on a relatively narrow matrix column. This can erode competence over time.

Using PPM forces a two-dimensional point of view that permits a company to be more precise about its distinctive competence. It helps bring management attention to critical process decisions and alternatives that could have been neglected otherwise.

Understanding the implications of a product-process combination

The nature of management problems change based on different combinations of product and processes. Interactions between the two determine which tasks will be critical for a given company or industry.

These movements in priorities are shown:

For a given product structure, a company with a competitive emphasis on quality or new product development would choose a much more flexible production operation than a competitor with the same product structure but following a cost-minimizing strategy.

Alternatively, a company that chooses a given process structure reinforces the characteristics of that structure by adopting the corresponding product/market structure.

The former approach positions the company above the diagonal, while the latter positions it somewhat below or along the diagonal.

Companies concentrating on the upper left of the PPM must decide when to drop or abandon a product or market (eventually, the jumbled shop process becomes unviable from a cost perspective), while those on the lower right must decide when to enter the market (the market must be ready for high volumes to justify capital investment).

PPM forces the management to think about the product-process fit, which is particularly useful in selecting and matching these two dimensions for a new product.

Organizing operations

PPM helps management align its operating units more effectively with individual tasks as the products and processes evolve.

For example, a company may produce washing machines for a fast-moving market using a highly automated assembly line; however, its follow-up spares may sell in low volume and require a process more flexible than the primary product. An undifferentiated production would make the process less efficient and ineffective for both product categories.

The choice of product and process structures also determines the manufacturing problems that will be important for management. They depend on the process stage (some of these management tasks are listed on the right side of the matrix above).

PPM helps perform a task-oriented analysis and avoids losing control over manufacturing that can result when a standard set of control mechanisms is applied to all products and processes.

PPM also helps many large companies that can (and do) produce multiple products in multiple markets. Since these products are often in different stages of the product life cycle, their manufacturing facilities must be separated and organized to meet the needs of each product. Sales volume is also an important consideration to make those manufacturing units competitive.

Using PPM to navigate changing dynamics

Irrespective of whether a company changes its product or process structure, external forces can often change its position on the matrix relative to competitors. If these changes and their implications go unnoticed, it could lead to severe internal problems.

PPM helps track the influence of changing market dynamics on a company’s position and avoid loss of focus:

Change in position

Any change in the product’s relative positioning or production processes without a corresponding change in the other reduces focus and creates difficulty in coordinating manufacturing and marketing.

For example, a company that automates its production process without understanding the marketing implications may impair its ability to compete compared to companies that have more closely coordinated and matched the changes in their product and process structures.

Another difficulty follows when a company tries to respond to a change in one dimension by broadening its activity on the other, such as responding to a product shift, not with a corresponding shift in the production process but by adding an additional process.

Loss of focus

Just as marketers segment markets and design products, prices, promotional strategies, and sales organizations to meet each segment’s specific imperatives, manufacturing processes, too, need a similar approach.

Unfortunately, the resistance to piecemeal changes and incremental expansion is much lower in manufacturing.

For example, a low-cost, highly specialized packaging company may augment its basic product lines with new, less standardized, higher-priced products in its quest for higher revenue and profits – thereby diluting its focus.

A company initially offering a standardized product line may, for example, attempt to diversify its products when faced with challenges from competitors targeting niche markets. Unlike competitors with optimized processes for such segments, its mass production methods become uneconomical for smaller volumes.

In both examples, if the company had considered coordinated, compensating changes to both the product and the process dimensions, it would have selected options that maintained or increased its competitive competence rather than tried to broaden its activity on one dimension or the other, which diluted its past competence.

PPM helps avoid such failures and can provide valuable insights for planning product and process changes. It concentrates management attention on decisions regarding both product and process activities.

Using PPM to plan growth strategies

Since growth planning concentrates management’s attention on both product and process decisions, PPM serves as a natural framework for guiding decision-making. Companies pursue four major types of growth:

- Type-1: Simple growth of sales volume within an existing product line and market.

- Type-2: Expansion of the product line within a single market using an existing process structure (product proliferation).

- Type-3: Expansion of the process structure (vertical integration).

- Type-4: Expansion into new products and markets.

Type-1: Simple growth

This involves increasing the volume using existing product lines and existing production processes. It requires highly stable conditions in terms of competitors, technology, and market tastes, with the only change occurring in the market size.

Unfortunately, such conditions are rare. Thus, even when a company limits itself to relatively narrow product and process activities, periodic changes will be required as markets and technologies mature.

A company that pursues simple growth must make two kinds of decisions:

- When to enter or exit a market.

- Select a product and process strategy consistent with market reality.

Entrance-exit strategies

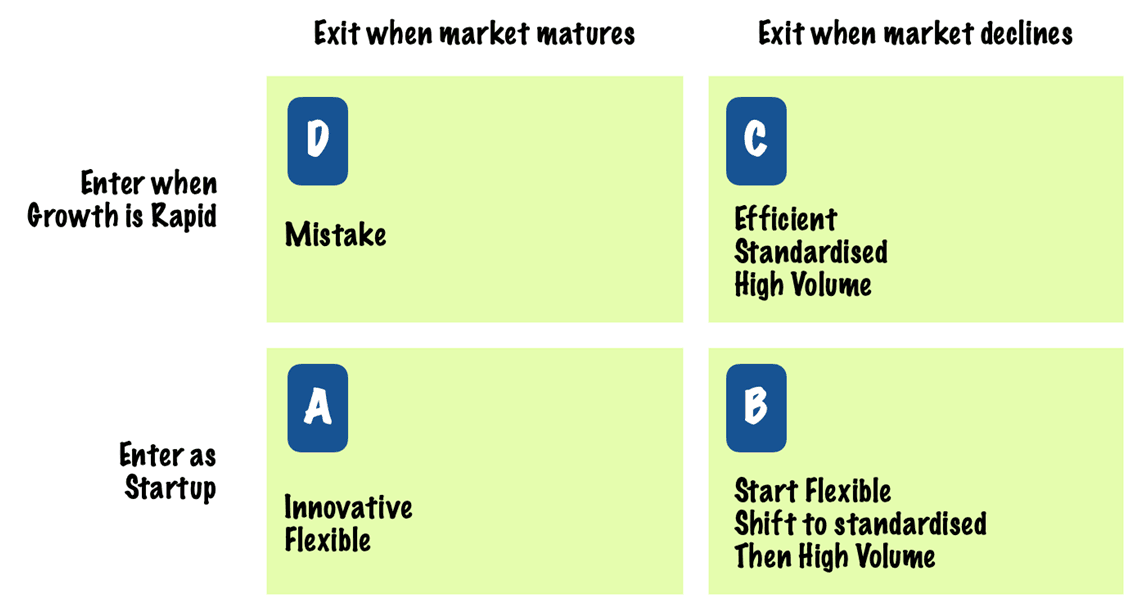

Any company must essentially choose between one of the four entrance-exit strategies:

- Enter early and exit the product line when technology stabilizes, profit margins narrow, and larger companies begin to appear. Exploit superior flexibility and technological skills to pivot to some new product.

- Enter early, grow with the industry, and seek to become a significant factor in the business throughout the product’s life cycle.

- Wait on the sidelines until some degree of product and process stabilization has occurred. Enter when market size justifies massive production, distribution, and marketing resources (typical of large companies).

- Delayed variation of strategy “C” where it’s too late to gain a sustainable market position. The company must hence withdraw without having an adequate return on its investment.

These combinations of entrance and exit strategies can be plotted on a 2×2 matrix as shown:

Selecting a product–process strategy

Once a company selects an entrance-exit strategy for a market, management must select a product and process development strategy. The available options can be viewed as possible paths on a PPM.

An industry roughly progresses down the diagonal of the PPM. It follows a composite pattern as companies tend to make only one kind of change at a time – either a product or a process change.

While the size and the frequency of these movements are dictated more by the rate of product maturation and technological innovation than by corporate decisions, a company can choose to “lean” in one direction or the other – moving roughly parallel to the diagonal but either above or below it – or attempt to stay as close to the diagonal as possible.

Maintaining a position above the diagonal will allow flexibility to quickly change products, volumes, and processes and reduce the company’s capital needs. However, it will make the company vulnerable to competitors who can undercut its price, offer better delivery, and possibly tighter product specifications.

Conversely, positioning below the diagonal may help achieve a significant competitive advantage in price and delivery but can lock the company into a set of facilities and manufacturing capabilities, making it challenging to respond to the market changes that usually accompany movement along the product life cycle.

PPM helps track a company’s position relative to the industry. It can alert when a company moves too far from the diagonal in either direction, making it dissimilar from its competitors and vulnerable to attacks.

This also ensures better coordination between marketing and manufacturing, aligns the two functions to develop complimenting skills and priorities, and prepares them to respond to different opportunities effectively.

Type 2: Product Growth

This type of growth represents a broadening of the product line and can occur in two ways: the first is adding more standardized products while maintaining existing, less standardized ones; the second is adding special features to an existing, more standardized product line.

The first kind, where new products are added while retaining parts of the existing product line, represents a shift to the left on the product dimension. These are triggered when marketing believes that “good service” requires a “full line” while manufacturing believes that new products will absorb some overhead and fixed costs.

The second kind, where features are added to products, also represents movement on the matrix from right to left and goes against the prevailing current of the product life cycle (which assumes continual standardization of products).

Both can put unreasonable strains on its production processes. As discussed in this article’s “organizing operations” section, PPM helps management align its operating units more effectively with individual tasks as the products evolve.

Type-3: Expansion of the process structure

Analogous to product growth, process structure expansion happens when a company maintains existing processes and adds either less standardized, more flexible processes (forward integration) or more standardized, less flexible processes (backward integration).

Such vertical integrations are not simple – they could mean producing an entirely different product at a very different point on the PPM. The company may have to consider an additional PPM for that part or raw material and develop very different strategies from those selected for the original product.

PPM helps develop new strategies that differ greatly from those selected for the original product. Without PPM, a company may be tempted to produce the new part with a process and an organizational structure that is completely inappropriate.

Type 4: New Markets

This is the most challenging of the four growth paths where a company enters a new market or introduces an entirely new product.

Entering a new market puts pressure on expanding the product line, forcing a horizontal retreat on the matrix. The business’s production and marketing sides encounter new challenges simultaneously.

While marketing tries to adapt to a new market for which its processes are not adequately suited, production tries to adapt to new products that strain manufacturing.

The PPM framework helps managers position themselves strategically along the two dimensions so that marketing and manufacturing are responsible for a restricted or focused set of product and process characteristics and don’t stray too far away from the PPM diagonal.

Summary

The PPM framework helps a company diagnose its strategic evolution, think creatively about possible future directions, and explicitly involve marketing and manufacturing in coordinating and implementing its competitive goals.

Companies can easily lose their way. Managers can use the PPM framework to:

- Determine the appropriate mix of manufacturing facilities, identify each plant’s critical manufacturing objectives, and monitor progress on those objectives.

- Review investment decisions for plant and equipment and whether they are consistent with product and process plans.

- Determine the direction and timing of significant changes to a company’s production processes.

- Evaluate product and market opportunities considering the company’s manufacturing capabilities.

- Select appropriate process and product structure for entry into new markets.

Sources

1. “Link Manufacturing Process and Product Life Cycles”. HBR, Robert H. Hayes and Steven C. Wheelwright, https://hbr.org/1979/01/link-manufacturing-process-and-product-life-cycles Accessed 22 Dec 2024.

2. “The Dynamics of Process-Product Life Cycles”. HBR, Robert H. Hayes and Steven C. Wheelwright, https://hbr.org/1979/03/the-dynamics-of-process-product-life-cycles Accessed 21 Dec 2024.