Change is a complex, multifaceted process that impacts every aspect of an organization, from activities and people to culture and structure. While research suggests that most change efforts fail [1], the need for change remains inevitable. The dynamic environment today adds an extra layer of urgency and complexity.

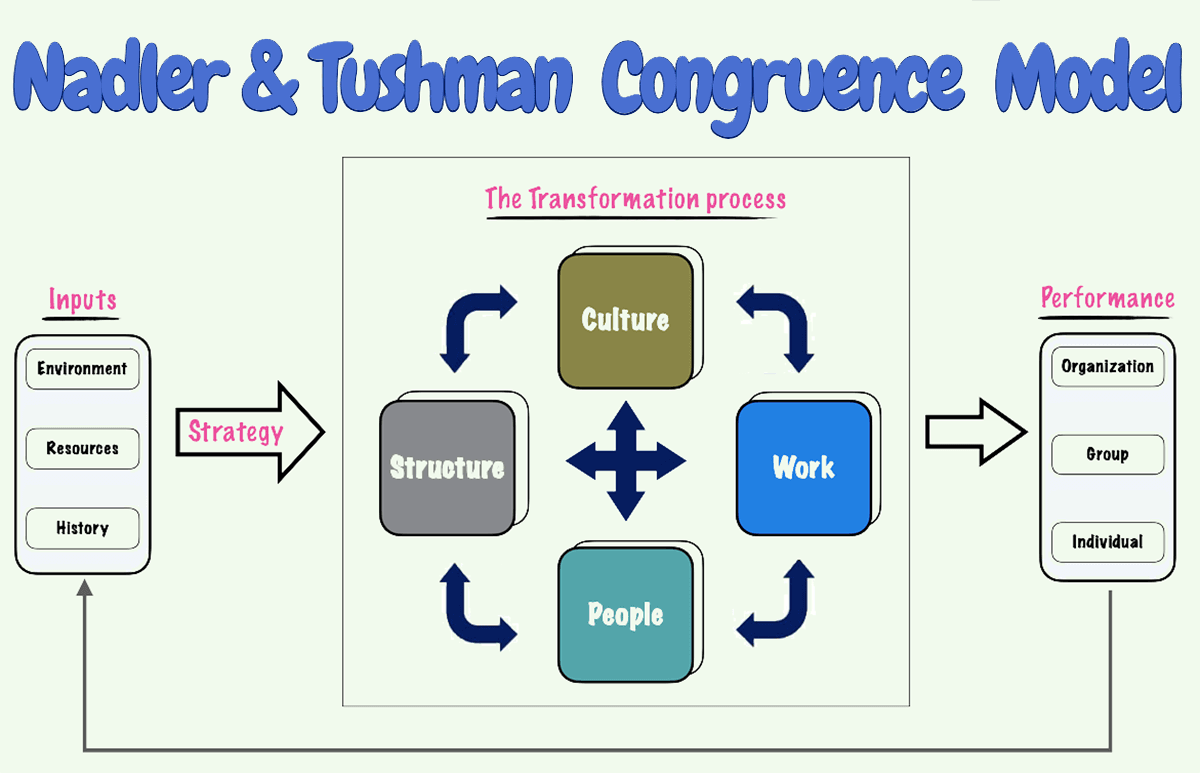

Organizations, much like living organisms, are ever-evolving systems. The Nadler-Tushman Congruence Model offers a powerful framework for viewing organizations not as static snapshots but as interconnected, dynamic systems in which changes ripple across various components.

Stressing the concept of congruence, the model helps executives diagnose issues, align processes, and manage change more effectively, ensuring a holistic approach to change management.

Open System and the Congruence Model

When asked to draw a picture of an organization, most managers imagine a version of the traditional, pyramid-shaped structure characterized by hierarchy. This traditional static structure assumes a stable configuration where jobs and work units are seen to be the most critical factors.

It excludes the interplay of important aspects, such as informal behavior, external influences, and power relationships. Organizations, however, behave like social organisms and, in many ways, display the same characteristics as natural systems.

For example, think of any organization and ask the following questions:

- Is the competitive environment today the same as a few years ago?

- Have new competitors, technologies, etc., altered the nature of competition?

- Is the organization structured and managed as it was in the past?

- Do employees use the same skills, knowledge, and techniques as they used to?

- Have customer demands of value, quality, delivery, and service remained the same?

Answers to such questions show that every component of an organization and its external environment changes constantly, and each change can potentially have serious ripple effects.

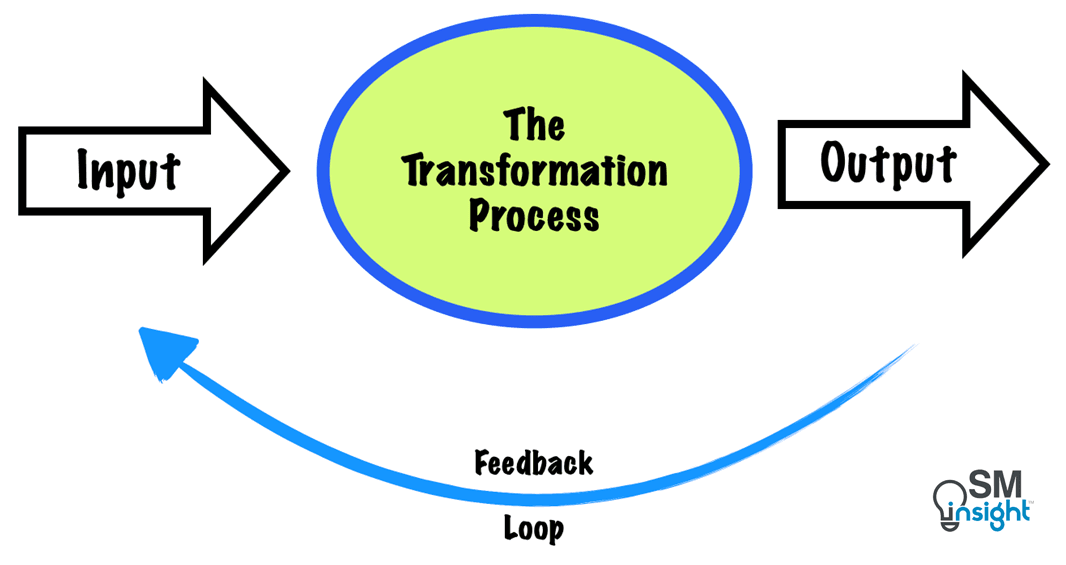

This makes the static model of organization design irrelevant as it fails to capture the dynamics of fluid relationships and does not support real-time information. Organizations are thus better understood as dynamic, open social systems with the capacity to create and use feedback:

This Open Systems Theory (OST) of understanding organizations originated in the 1960s when researchers at the Harvard Business School and the University of Michigan started exploring similarities between naturally occurring systems and human organizations. By the mid-1970s, the theory was widely accepted by organization development practitioners.

Organization theorists David Nadler [1] and Michael Tushman [2], influenced by OST and the works of Katz and Kahn on the social psychology of organizations [1], began developing a model that could reduce managers’ information complexity. This led to the development of the Nadler-Tushman congruence model.

The model provides a simple yet pragmatic approach to understanding organizational dynamics and indicates which components are most important in unraveling the mysteries, paradoxes, and apparent contradictions in organizations.

Elements of the Nadler-Tushman Congruence Model

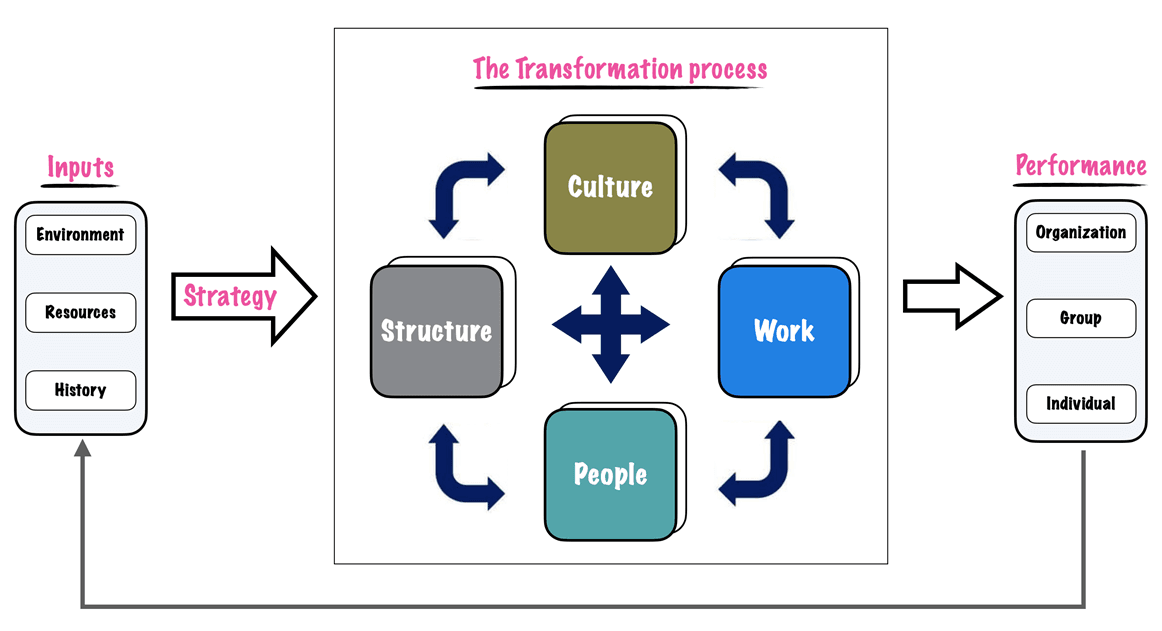

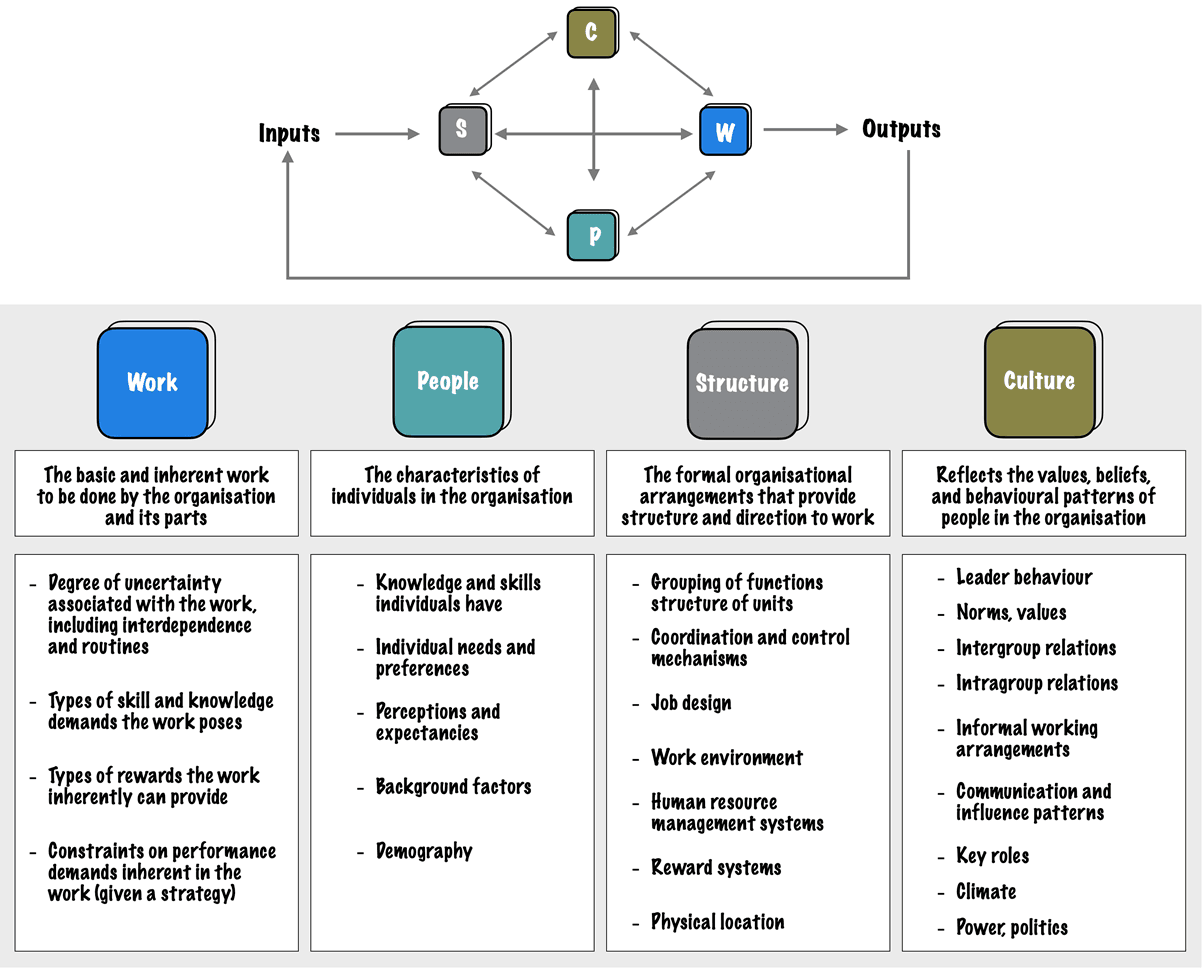

The Nadler-Tushman congruence model attempts to understand performance by treating the organization as a system consisting of certain basic components. These components are inputs, strategy, the organization’s transformation process shaped by its culture, work, structure, and people, and finally, the output, which is the organization’s performance as shown:

It focuses primarily on the relationships and interactions between these components and how they affect performance and output. In other words, congruence measures how well pairs of components fit together.

For an organization to function well, its components must be congruent. This means that the needs, demands, goals, objectives, and/or structures of one component must be consistent with those of the other.

Each of these components is explained in more detail:

Inputs

An organization’s input includes the elements that, at any point in time, constitute the set of “givens” with which it has to work. There are three main categories of input, each affecting the organization in different ways:

Environment

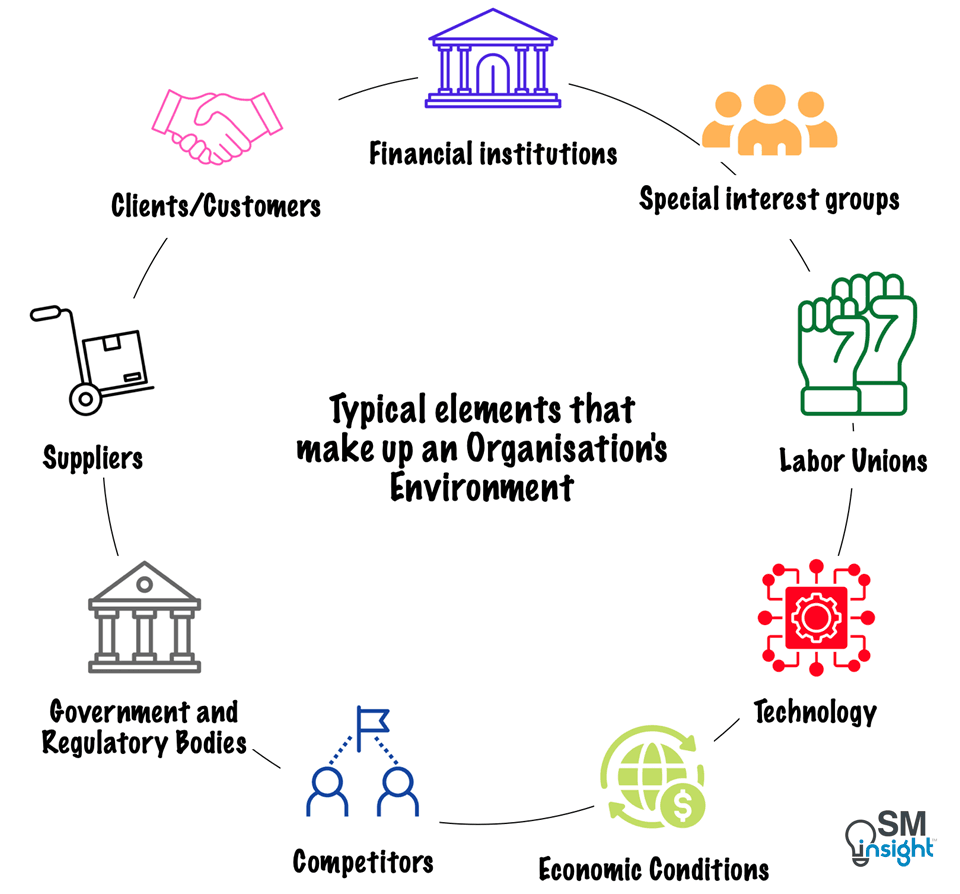

Every organization functions within and is influenced by its larger environment, which includes people, other organizations, social and economic forces, and legal constraints. Specific elements that make up an organization’s environment are shown:

The environment affects the way organizations operate in three significant ways:

- It shapes the demand: organizations must manage the demands imposed by the environment. For example, customer preferences will shape the quality, quantity, and price of goods and services.

- It imposes constraints: the environment often imposes constraints, which can range from limitations due to scarce capital, insufficient technology, legal prohibitions, government regulation, court action, or collective-bargaining agreements.

- It provides opportunities: the environment offers new opportunities, such as the potential for new markets resulting from technological shifts, deregulation, good economic conditions, or the removal of trade barriers.

Every organization is directly influenced by its external environment, and nearly all large-scale change originates in the external environment.

For example, technological shifts led to the rise of e-commerce giants like Amazon, which forced traditional brick-and-mortar stores to adapt or face closure. Retailers must now blend in-store experiences with online shopping to meet changed consumer expectations [3].

In the energy sector, a focus on environmental sustainability forced oil & gas firms to diversify into renewables, while utility companies are increasingly focused on solar, wind, and energy storage as part of a broader push toward clean energy solutions [4].

Resources

Resources include the full range of assets to which an organization has access. This could be employees, technology, capital, information, and even less tangible assets, such as how an organization is perceived in the marketplace, its reputation among customers, investors, regulators, and competitors, or a positive organizational climate.

For instance, Apple leverages skilled talent to drive innovation in hardware, while its strong brand identity, focused on premium design, user experience, and ecosystem integration, ensures customer loyalty and investor confidence.

SpaceX has developed proprietary rocket propulsion technologies that place it far ahead of its competitors, enabling it to lead the aerospace sector.

Amazon uses consumer purchasing data and behavioral insights to tailor its marketing and improve operational efficiency. Its reputation as a customer-centric company with a reliable, fast delivery system has helped it dominate the e-commerce landscape.

Nike enjoys a powerful brand reputation tied to high-performance, high-quality sportswear. This is reinforced by endorsements from top athletes, fostering consumer trust and loyalty.

Google’s (Alphabet) dominant position in search generates vast capital, allowing it to invest in new technologies and place risky bets, even though not all ventures are successful.

These examples show how resources can place organizations in a position to win or lose.

History

Organizational history can have powerful, unnoticed effects on its present behavior. Its capacity to act in the present or the future depends on the crucial developments that shaped its past. This includes strategic decisions, the behavior of key leaders, responses to crises, and the evolution of values and beliefs.

The older and more distinguished an organization, the greater the influence of its history. Efforts toward innovation and change can be severely constrained if the organization is held hostage to its past by its history.

Managers must also understand who their predecessors were, what legacy they left, and what they did and did not do. These prior actions shape current habits. If these precedents are ignored, managers risk falling victim to ghosts of leadership habits from the past.

For example, when Satya Nadella took over as CEO at Microsoft, he knew his predecessors had focused on traditional software licensing models to establish Windows dominance. This approach slowed Microsoft’s plans to embrace cloud computing. Recognizing this, Nadella built on the organization’s strengths while steering it toward a cloud-first strategy, enabling it to become a leader [5].

Thus, understanding Inputs, environmental conditions, organizational resources, and history, helps make better decisions about an organization’s strategy, objectives, and vision. These inputs cannot be changed in the short run—they are the “givens” or the settings within which the organization must operate.

Strategy

Every organization must have an articulate vision of how it intends to compete and what kind of organization it wants to be, given the realities of its environment. From that vision flows its strategy—a set of business decisions and choices about markets, offerings, technology, and distinctive competence.

An organization’s strategy must be informed by the following questions:

- What products or services do we offer? The first strategic decision is the choice and range of offerings.

- Who are our customers? The second strategic decision is to choose the target market and customer. Managers must determine who their customers are, whether internal or external. Any change in customers also reflects a shift in the business strategy.

- What technology will help us win? Managers must be clear about their technological choices in service of their unit’s business strategy. Since no organization or business unit can afford to invest in all relevant technologies, choosing the right one and how much to invest are critical to success.

- What is our unique value proposition? Why would the targeted customers buy from us?

- Is the competitive timing right? When should we move into a product class? This timing decision can have significant consequences for resource allocation and organization design. A first-mover advantage [6] is not beneficial in all markets,

It must be carefully evaluated whether the product or service must attempt to gain brand awareness and market position by being first or should wait until the market has developed and consumer tastes are known. - Value—how do we retain, as profit, a portion of the value we deliver to customers? How do we protect profits from competitor imitation and customer power?

Organizations making wrong strategic decisions will underperform or fail. No amount of design can compensate for an ill-conceived strategy. Likewise, no matter how good a strategy looks, it can’t succeed unless it’s consistent with the organization’s structural and cultural capabilities.

The challenge is to design and build an organization capable of accomplishing strategic objectives, considering its environmental threats and opportunities, internal strengths and weaknesses, and the performance patterns suggested by its history. These long-term strategic objectives must then be refined into internally consistent short-term objectives and supporting strategies.

Output

Output is a broad term that describes an organization’s performance and effectiveness. It also includes the performance of individuals and groups within the organization, as they contribute directly to overall performance.

For instance, changes in individual and collective attitudes and capabilities—such as satisfaction, stress, poor morale, or the acquisition of important experience—can all be seen as output or the results of the transformation process.

At the organizational level, performance can be evaluated using three criteria:

- How successfully has the organization met the objectives specified by its strategy?

- How well has the organization used available resources to meet its objectives? Has it developed new resources rather than “burning up” existing ones?

- How well does the organization reposition itself to seize new opportunities and ward off threats from the changing environment?

Comparing output with the objectives articulated in the organization’s strategy helps spotlight activities where output falls short of objectives and provides essential guidelines for determining where to focus redesign efforts.

The Organization as a Transformation Process

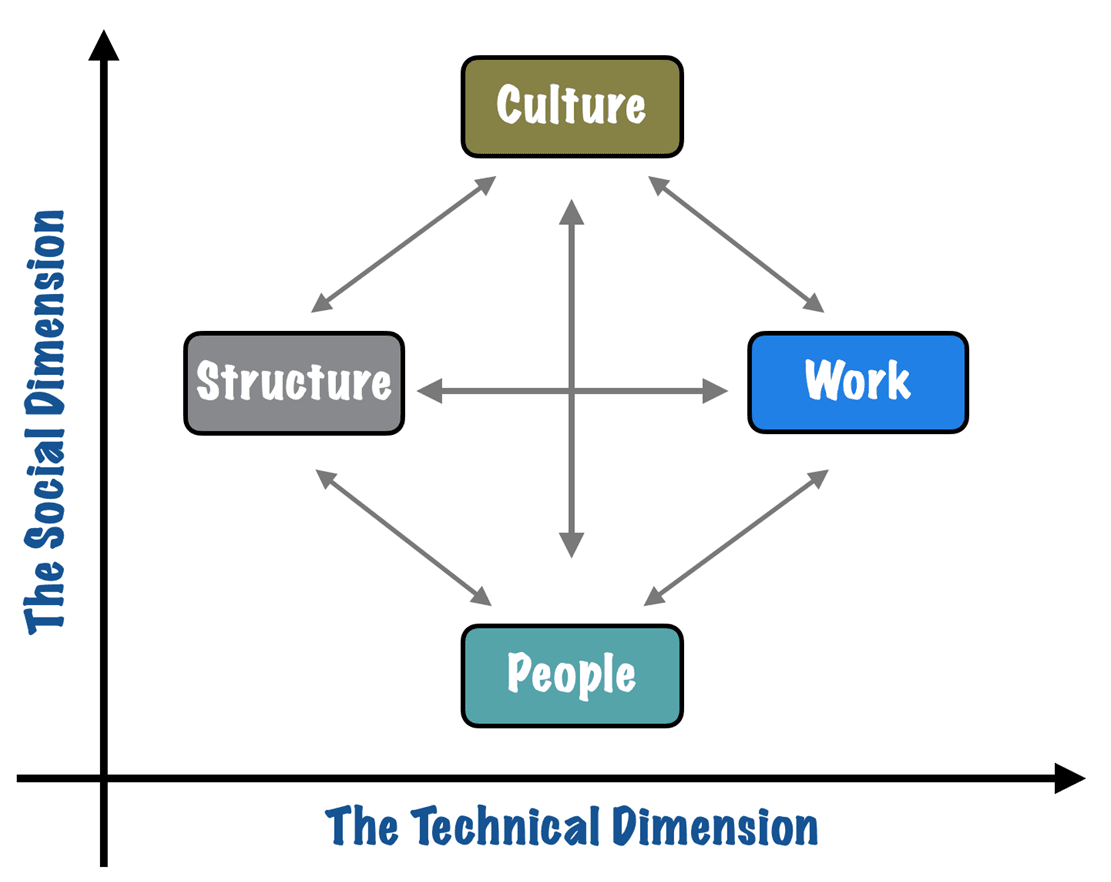

At the heart of the congruence model is the transformation process, which draws upon the input implicit in the environment, resources, and history to produce a set of outputs. This transformation process embodies the organization and contains four key components:

A key challenge for organizational designers is to find the best way to configure these components to create the output necessary to meet the strategic objectives. To do this, it is essential to understand each component of the organization and its relationship with others.

The Work

Work includes all basic and inherent activities the organization and its units must engage in to further the company’s strategy. The performance of work is one of the primary reasons for the organization’s existence.

Organizations must analyze work from a design perspective by understanding the nature of the tasks to be performed, the workflow patterns, and its more complex characteristics—knowledge or skills it demands, the rewards it offers, and the stress and uncertainty it involves.

The People

It is important to ensure a fit between the important characteristics of people responsible for performing work and the demands of the core work. That means looking at the workforce in terms of skills, knowledge, experience, expectations, behavior patterns, and demographics and asking questions such as:

- What knowledge and skills do they bring to their work?

- What are their needs and preferences? What personal and financial rewards do they expect to flow from their work?

- What are their perceptions and expectations about their relationship with the organization?

- What are their demographics, and how do they relate to their work?

The Structure

The structure represents the formal organizational arrangements. This includes explicit processes, systems, and procedures developed to organize work and to guide individuals in performing activities consistent with the organization’s strategy.

The Culture

Culture represents the informal organization that coexists alongside the formal arrangements. It is usually a set of informal, unwritten guidelines that exert a powerful influence on the behavior of groups and individuals.

Also referred to as the operating environment, culture encompasses a pattern of processes, practices, and political relationships that embody employees’ values, beliefs, and behavioral norms.

Culture has a powerful influence and can sometimes supplant formal structures and processes, especially when the latter become misaligned with the evolving realities of the workplace.

The Concept of Congruence

At any given time, each of the organization’s components is (to some degree) congruent with others. Congruence here means the degree to which one component’s needs, demands, goals, objectives, and/or structures are consistent with another. It’s a measure of how well pairs of components fit together.

The Congruence hypothesis states that all else being equal, the greater the total degree of congruence (or fit), the more effective the organization will be. Stellar talent, streamlined structures and processes, cutting-edge tech, and a high-performance culture do not amount to anything unless they fit well.

Think of it this way: theoretically, you could build a car with Porsche’s engine, BMW’s transmission, and Rolls Royce’s interiors. However, putting them together and you don’t get much because a car’s performance depends on how well parts fit and work together, not how good they are individually.

Thus, Nadler-Tushman’s concept of congruence suggests that the interaction between each set of organizational components is more important than the components themselves. In other words, the degree to which the strategy, work, people, formal organization, and culture fit will determine the organization’s ability to compete and succeed.

Because an organization’s components can be configured in different ways to achieve the desired output, there is no one best way. It is about determining the combinations of components or architecture that will lead to the greatest degree of congruence.

Organizational Diagnosis with the Congruence Model

The congruence model is more than an interesting way of thinking about organizational dynamics. Its real value lies in its usefulness as a mental checklist, a framework for identifying the root causes of performance gaps.

Prerequisites To Using The Congruence Model

In his book, Winning Through Innovation [7], Tushman has proposed the following guidelines to identify potential pitfalls and enhance the likelihood of success when using the model:

1. Define the unit of analysis

Managers in different positions may have different problems and develop different diagnoses for the same performance gaps. It is important to clarify who owns the problem, what can be controlled, and what cannot.

Hence, the first step is to clarify who the manager is and identify performance and opportunity gaps from the manager’s perspective. If a manager defines a problem from the boss’s or CEO’s perspective, many solutions may not be implementable if they exceed the manager’s control.

2. Evaluate The Strategy And Vision

Organizations exist to accomplish strategic goals. If the strategy emphasizes the wrong product or service for the wrong market, with the wrong technology and bad timing, no amount of organizational problem-solving can help. Tight alignment with the wrong strategy will only ensure quick failure.

3. Perform Comprehensive Diagnosis

A diagnosis must consider all four organizational building blocks. Focusing on one or two of them can lead to misalignment with other components, going against the principle of congruence. For instance, cultural inertia and political resistance can wreck reengineering efforts when managers ignore the informal organization.

4. Identify The Type Of Change Needed

The type of change required depends on the number of inconsistencies discovered. Incremental change is possible if a diagnosis reveals incongruencies between only one or two organizational building blocks.

However, a discontinuous change is needed when the diagnosis shows inconsistencies among three or more building blocks (e.g., new critical tasks require changes in people, formal arrangements, and culture).

Identifying the type of change early is important as it can impact how a manager thinks about and initiates the change.

5. Be Flexible About The Choice Of Intervention

There are many possible interventions for any diagnosis, and as such, there is no one best solution. Different managers may choose to intervene in different ways. What is important is that the intervention must address inconsistencies identified in the diagnosis and drive greater congruence among the building blocks.

6. Some Gaps Can Demand Additional Managerial Skills

The congruence model focuses on problem definition and root cause analyses from a particular manager’s position. Sometimes, a diagnosis may reveal a root cause that lies outside the control of the focal manager.

In such circumstances, the manager will need skills to manage their boss, peers, customers, or those outside the unit. The diagnostic work will only lead to an insightful but frustrated manager without such skills.

7. Collect Data, Be Systematic

The congruence approach emphasizes gathering data before taking action. This is often unnatural for managers, who are used to immediate, decisive action. The pressure of day-to-day business means they lack the time to be systematic. Managers must step back, gather data before intervening, and be systematic in their diagnoses.

8. Address “What” As Well As The “How”

Successful problem-solving is a function of what managers do and how they do it. Knowing what to do is half the solution. Being able to implement the changes is equally important. Great ideas executed poorly are as bad as poor ideas executed flawlessly.

9. Focus On The Process

The benefits of using the congruence model are accrued over time, provided managers follow a disciplined problem-solving approach and learn from their actions. Because different managers develop different diagnoses for the same problem, there can be multiple possible interventions.

Rather than focusing on the correct intervention to solve a particular problem, managers must focus on the process they use to attack the problem. Mistakes will be made, both in diagnoses and in action. One should not be paralyzed by such mistakes but learn by doing.

A General Approach to Using the Congruence Model

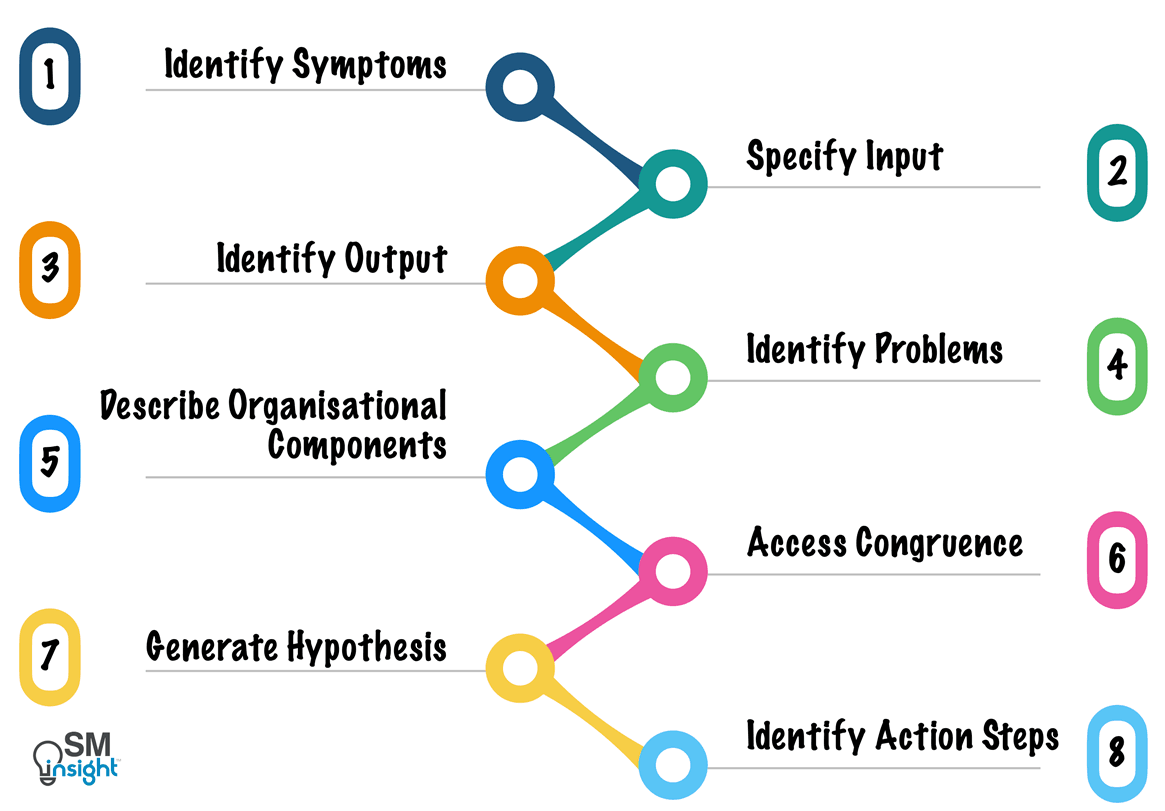

A general approach to using the congruence model for organizational problem-solving involves eight steps, as shown:

1. Identify Symptoms

While initial information on symptoms of poor performance may not pinpoint real problems or their causes, it is still useful to focus the search on finding more complete data.

For example, symptoms of problems in a retail chain may include declining year-over-year sales, high employee turnover, and rising customer complaints about service quality. Identifying these symptoms will help the chain focus on uncovering deeper issues that may not be immediately obvious.

2. Specify Input

With the symptoms in mind, the next step is collecting data concerning the organization’s environment, resources, and critical aspects of its history. Input analysis also involves identifying the organization’s overall strategy, its core mission, supporting strategies, and objectives.

In the retail chain example, a deeper analysis might uncover environmental factors such as heightened competition from e-commerce platforms and shifting consumer preferences. Resource-related challenges could include outdated POS systems, undertrained staff, and a constrained marketing budget.

The organization’s history might also highlight a strong in-store service culture but limited adaptation to digital transformation. Its mission may emphasize “personalized customer service,” but the strategy to achieve it in the context of current challenges may be missing.

3. Identify Output

Analyze the organization’s output at the individual, group, and organizational levels. This analysis involves defining precisely what output is required at each level to meet the overall strategic objectives and then collecting data to measure precisely what output is being achieved.

For the retail chain, output analysis could reveal factors such as frontline staff feeling overworked and disengaged (individual) and a lack of teamwork between store managers and regional leadership (group). Consequently, the organization faces declining sales.

4. Identify Problems

The next step is pinpointing specific gaps between planned and actual output and identifying the associated problems—organizational performance, group functioning, or individual behavior.

Whenever information is available, it is useful to identify the costs associated with problems or failure to fix them. Such costs might be actual, such as increased expenses, or missed opportunities, such as lost revenue.

The retail chain, for example, might notice its targets are missed by 20%, and turnover is 30% higher than the industry average, leading to increased recruitment and training expenses.

5. Describe Organizational Components

In this step, the analysis goes beyond problem identification to focus on causes. It begins with data collection on each of the organization’s four major components.

Not all problems, however, will have internal causes. Some may result from external developments—a shift in the regulatory environment, a new competitor, or a major technological breakthrough—that make existing strategies insufficient or obsolete.

It’s important to consider strategic issues before focusing too narrowly on organizational causes for problems; otherwise, the organization is in danger of merely doing the wrong thing more efficiently.

In the case of the retail chain, data could show that:

- Employee roles focus on sales but don’t include skills for handling new e-commerce trends (Work).

- Staff lack motivation and skills training (People).

- The organization is hierarchical, slowing decision-making and innovation (Structure).

- A resistance to change and focus on “how things used to be” (Culture).

- Competitors use AI for personalized online shopping (External Factors).

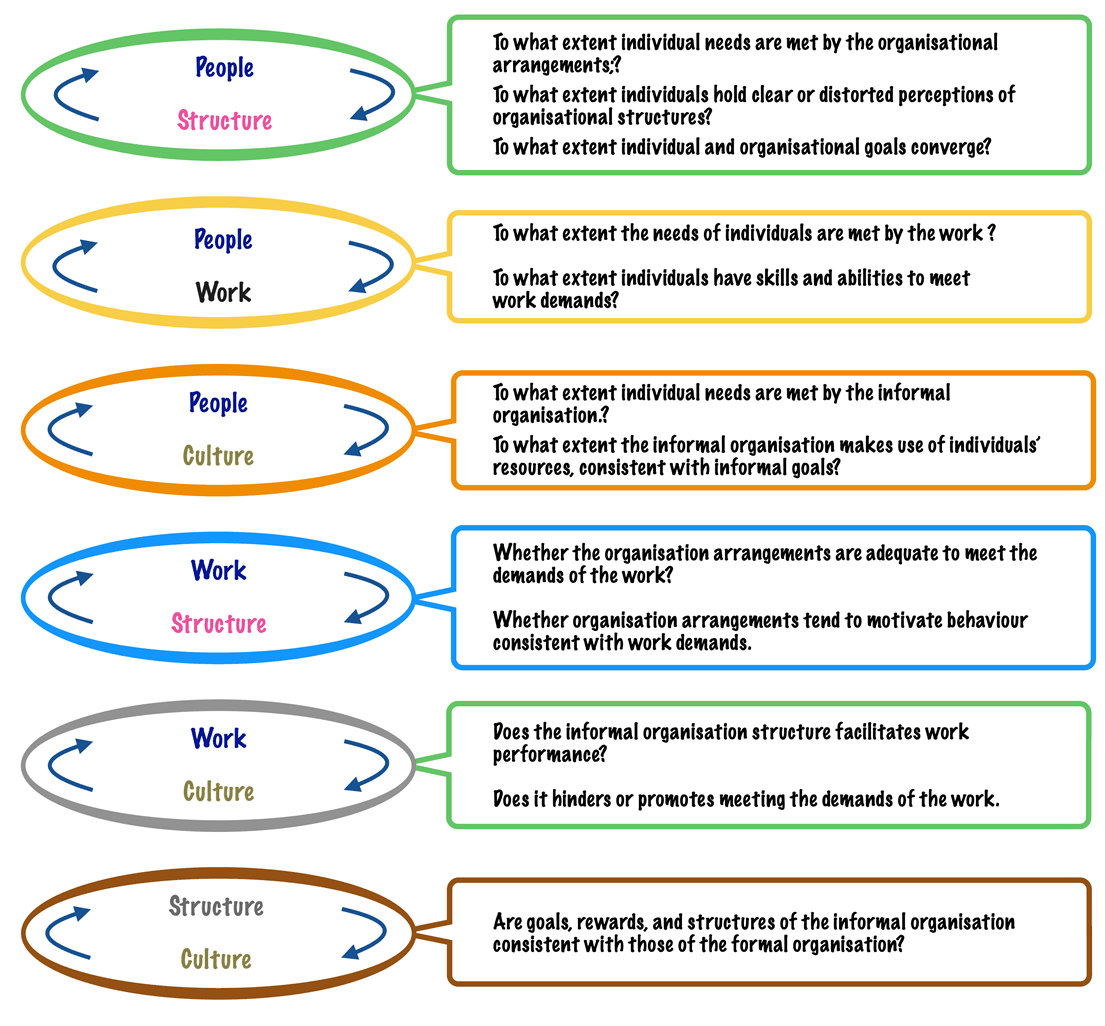

6. Assess Congruence (Fit)

The next step is to assess the degree of congruence or the fit among various components. Sources of poor fit can be determined by asking the following questions:

Determining The Degree of Fit in an Organization

7. Generate Hypotheses About Problem Causes

Scan for correlations between poor congruence and problems that are affecting output. Once these problem areas have been identified, available data must be used to test whether poor fit is, indeed, a key factor influencing output and a potential leverage point for forging improvement.

In the retail chain, a possible hypothesis could be that outdated training and tools reduce employee engagement and effectiveness or that a hierarchical structure prevents quick adaptation to market changes, harming competitiveness.

8. Identify The Action Steps

The final stage is to identify action steps, ranging from specific changes aimed at relatively obvious problems to more extensive data collection. This also requires predicting the consequences of various actions, choosing a course of action, implementing it, allowing time for the process to run its course, and evaluating the impact.

In the retail chain’s case, examples of short-term actions could include investing in staff training programs for digital tools and customer service and upgrading the POS system to improve efficiency.

Long-term actions could include revamping the organizational structure to improve agility, developing a hybrid strategy combining strong in-store service with e-commerce options, and measuring success through improved sales growth, as well as reduced turnover.

Benefits of the Congruence Model

The congruence model’s most obvious benefit is that it provides a graphic depiction of the organization as a social and technical system.

The horizontal axis—the work and the formal organization—can be seen as the technical dimension, while the vertical axis—the people and the informal organization—makes up the social dimension. The principle of congruence ensures either axis is not ignored.

The horizontal axis can also be seen as the organization’s hardware, while the vertical axis is its software.

A second benefit of the congruence model is that it avoids strapping intellectual blinders on managers as they think through the complexities of change. The model does not favor any particular approach to organizing. It recognizes that there is no one best structure or culture, and what matters the most is fit. This means managers are not burdened to copy competitors’ strategies, structure, or culture but are encouraged to develop one that accurately reflects the organizational realities.

A third benefit of the model is it helps understand the dynamics of change by predicting its impact throughout the organizational system. Major changes often originate in the external environment and become evident when comparing actual output to expectations. While most focus solely on strategy and formal structures, the congruence model extends the analysis to the informal organization, including its influence on culture.

Thus, the congruence model provides a general roadmap, a starting point for fundamental enterprise change. It is a conceptual framework for a change process that involves gathering performance data, matching actual performance against goals, identifying the causes of problems, selecting and developing action plans, and, finally, implementing and evaluating the effectiveness.

Sources

1. “Do 70 Per Cent of All Organizational Change Initiatives Really Fail?”. Mark Hughes, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233202794_Do_70_Per_Cent_of_All_Organizational_Change_Initiatives_Really_Fail. Accessed 9 Jun 2025.

2. “David A Nadler”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_A._Nadler. Accessed 09 Jun 2025.

3. “Michael L. Tushman”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_L._Tushman. Accessed 09 Jun 2025.

4. “The social psychology of organizations.”. Katz & Kahn, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1966-35011-000. Accessed 03 Jun 2025.

5. “Competing by Design: The Power of Organizational Architecture.” David Nadler and Michael Tushman, https://www.amazon.com/Competing-Design-Power-Organizational-Architecture/dp/0195099176. Accessed 03 Jun 2025.

6. “We wouldn’t have ecommerce without Amazon.” Quartz, https://qz.com/1688548/amazons-control-of-e-commerce-has-changed-the-way-we-live. Accessed 04 Jun 2025.

7. “Top Oil Companies Investing In Renewable Energy”. The Motley Fool, https://www.fool.com/investing/stock-market/market-sectors/energy/best-oil-companies-investing-in-renewable-energy/. Accessed 04 Jun 2025.

8. “How Satya Nadella tripled Microsoft’s stock price in just over four years.” CNBC, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/07/17/how-microsoft-has-evolved-under-satya-nadella.html. Accessed 04 Jun 2025.

9. “First Mover Advantage Explained”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/first-mover-advantage/. Accessed 08 Jun 2025.

10. “Winning Through Innovation: A Practical Guide to Leading Organizational Change and Renewal”. Michael L. Tushman, https://www.amazon.com/Winning-Through-Innovation-Practical-Organizational/dp/1578518210. Accessed 8 Jun 2025.

11. “The Congruence Model A Roadmap for Understanding Organizational Performance”. Mercer Delta Consulting, LLC, https://courseapps.online.mbs.edu/courses/MBA/BUSA90225_Managing_People/Documents/Week1/the-congruence-model-a-roadmap-for-understanding%20%282%29.pdf. Accessed 9 Jun 2025.