Change is the only constant in any business environment—a continuous, inevitable change that envelopes and influences most organizational decisions. No sensible business decision can be made without considering both the world as it is and the world as it could be.

Scenario planning is a start and can help organizations improve decision-making by considering alternatives, assigning probabilities to expected future outcomes, formulating a comprehensive and cohesive strategy, and, ideally, developing contingency plans.

However, even with all these advantages, scenario planning is still limited because it is fundamentally biased by the views of people who develop it and, therefore, is limited to the extent of their imagination.

In the words of the Nobel Laurette Thomas Schelling—”there is nothing harder to do than to come up with a list of all the things you have not thought about.” [1]

This is where business wargaming helps. It seeks to answer questions such as:

- What should a firm do when its industry is consolidating, competitors are making quick moves, and there seem to be no good partners (Example: Airline industry consolidation in the 1990s).

- Is the business model in our industry changing? Will we lose control over our market? Should we embrace new models, defend the status quo, or both? (Example: automobile industry in the age of electric vehicles and sustainability.)

- Is our industry/product becoming increasingly commoditized? Can we still make money? Should we close and focus on alternative business opportunities? (Example: telecommunications services moving toward standardization, leading to price wars.)

- How resilient is our business? What happens if? Where is the next threat coming from? How much should we invest in countermeasures?

By simulating competitive scenarios, testing strategies, and analyzing potential outcomes, wargaming enables firms to answer such difficult and seemingly uncertain questions in a controlled and risk-free environment.

History of Wargaming: Military to Business

Business wargaming grew out of military wargaming, which has been used to prepare military leaders for unforeseen circumstances on the battlefield since ancient Greece and even earlier.

In 1811, the Prussians introduced a three-dimensional “game board” to add reality to the play. The U.S. Naval War College started using wargaming in 1887. In the 1930s, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz could predict (except the kamikazes!) and play out virtually all the World War II battles of the Pacific [2].

In the post-World War II era, military research was dominated by civilians, focusing on operations research and systems analysis. Consequently, with a few exceptions, the traditional wargaming discipline lost more ground and supporters.

While military applications of wargaming were declining, academic strategists and political scientists began applying wargaming to political issues and behavior, leading to the political-military games in the USA (Germany and Japan had pioneered this during the 1930s) [3]

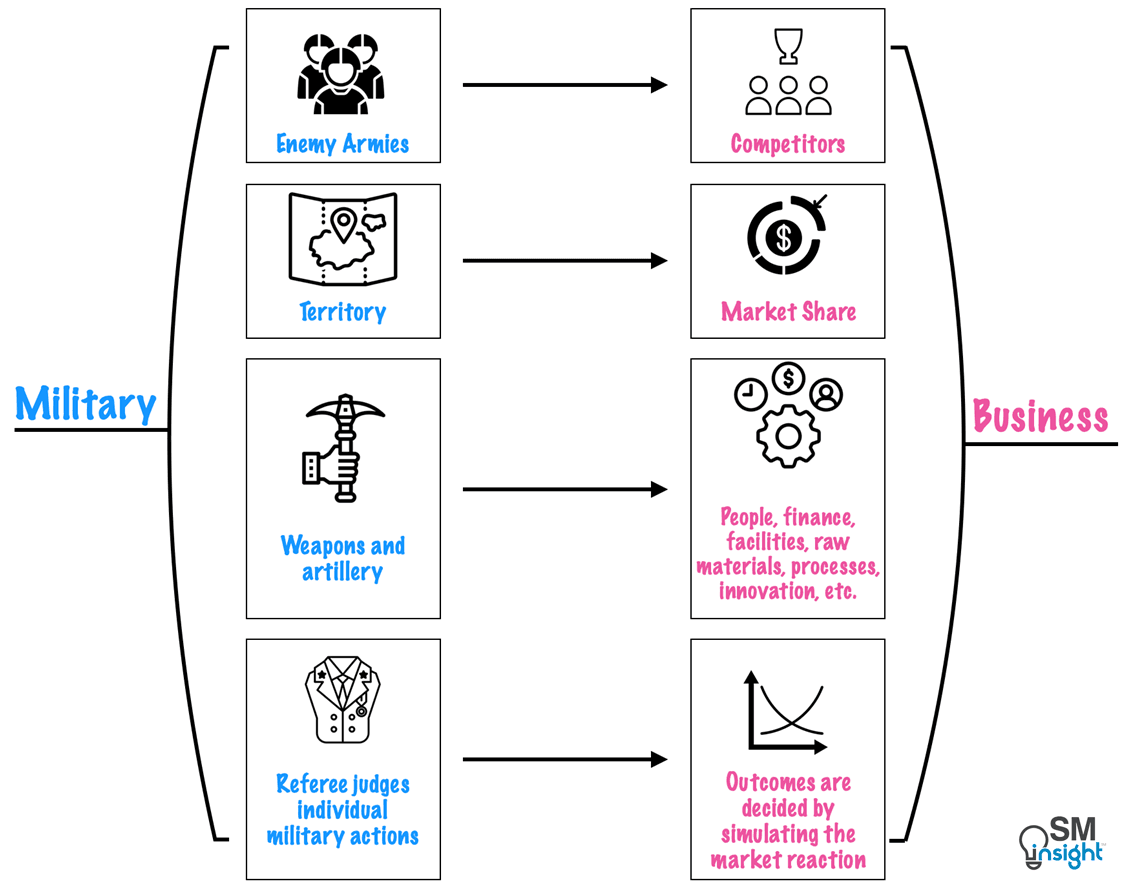

Following this evolution in the military and political context, wargaming techniques began to be applied to the business world, mainly because many elements of classical military wargames were transferable to the business context:

An article in the Harvard Business Review from 1958 mentioned the first application of wargaming methodology in a business context [4].

Initially, business wargaming was mainly used for education and training. By the mid-1980s, its focus shifted to providing competitive intelligence by analyzing competitors’ actions. Eventually, its application expanded to include strategy formulation.

The global strategy and technology consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton [5] was the first to establish a full-scale wargaming team consisting of several ex-Navy and ex-military experts who systematically developed the scope of possible business applications.

The firm has conducted hundreds of simulations not only for businesses but also for numerous governmental and non-profit organizations across the globe.

Today, business wargaming is widely used in the corporate world to assess and pressure test strategies, investigate market opportunities, identify internal shortcomings, train, and test strategists, encourage cross-departmental communication, and spark creativity to challenge the status quo.

Anatomy of a Business Wargame

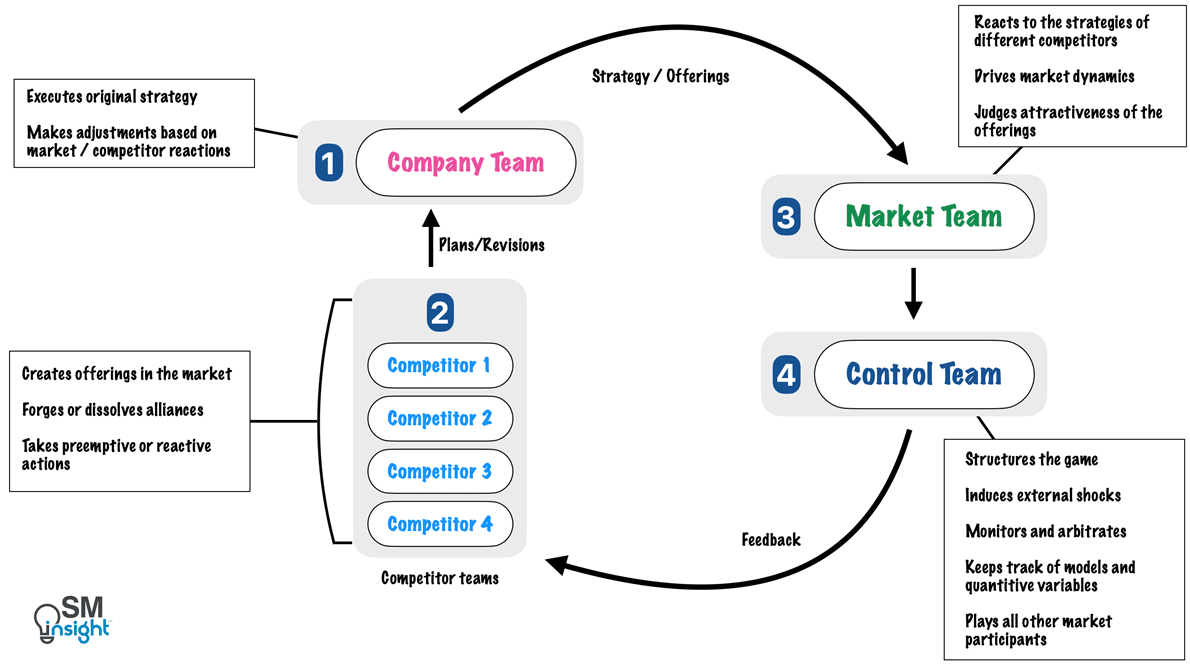

Any business wargame, at a fundamental level, contains four basic elements: the company team, the competitor team(s), the market team, and the control team:

The Company Team

The company team represents the company conducting the wargame and aims to answer key strategic questions. This team comprises senior managers from within the company and typically starts the game by executing its current strategic plan.

If a company deliberately wants to test alternative courses of action, the team may execute another hypothetical strategy or test an alternative business plan.

In executing its strategy, this team has all the liberty it would have in the real world—it can form or dissolve alliances, conduct mergers and acquisitions, or do anything else as long as it is within the boundaries of reality and the means of the company’s resources.

In addition to executing the original strategy, this team must also gauge and constantly adjust moves based on competition and market team(s) reactions.

The Competitor Team(s)

Competitor teams, like the company team, are also staffed with senior managers from within the company. These managers are forced to adopt the role of their competitors and view their company from that perspective.

To facilitate the transition into their new role, they receive a “gamebook,” which provides the most important facts about the company they are required to play and information on any other team. Coupled with the knowledge of their own company’s weaknesses, these teams become formidable adversaries to the company team.

Only the most significant competitors are represented by individual competitor teams. Smaller competitors are consolidated into a group of competitors or represented by the control team.

Competitor teams can take both preemptive and reactive actions, create offerings in the market, and forge or dissolve alliances.

The Market Team

This team represents the market participants and judges the relative attractiveness of all the companies’ offerings. It may comprise market experts from within the client organization, external experts, or a combination.

Typically, the market team forms a focus group that uses research, experience, and intuition to award market shares. It bases its decision and moves on hard data from the competitor teams at specified times during the simulation.

However, the market team also considers how well the message is communicated and the respective teams’ unique selling proposition (USP) in relation to one another and the rest of the market.

In short, the market team reacts to competitors’ strategies, drives market dynamics, and judges the attractiveness of different offerings.

The Control Team

The control team comprises wargaming experts, industry experts, and typically the company’s Chief Executive Officer or senior executives.

This is the team that runs the show. Its primary role is to structure and run the simulation, i.e., ensure that the schedule is adhered to, rules are observed, and presentations and feedback are given appropriately and at a level of detail/structure. The team also calculates the quantitative variables based on the feedback from the market team.

It provides the company and competitor teams with the outcome, typically including the major positions of an income statement or cash flow. In some instances, the control team will also introduce “shocks,” which are interventions to force the teams to address certain topics or go in a certain direction.

For example, announcing a product defect that calls for a recall or inducing product safety concerns that may call for a special approach to communication.

The control team also adopts the role of all other stakeholders not explicitly played in the simulation. Such stakeholders can be smaller competitors, regulators, or interest groups.

For instance, when faced with a proposed acquisition deal, experts of the control team will assume the role of the target company’s board of directors and decide whether to accept the deal.

Simulating the game

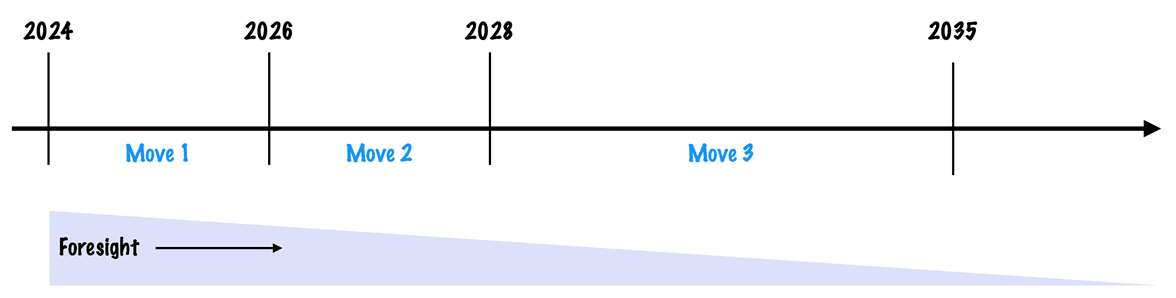

Business wargaming involves simulating a certain timeframe in real life. It typically evolves over three moves, with the first move always starting with the present and based on currently available data. The time frame for each move can vary from a few months to years to even several decades.

Every move is a decision cycle, which begins with the competing teams reviewing their strategy and taking their first actions toward an outcome.

Such actions could include launching new products or services, forging alliances, investing in capacity or new markets, or running communication campaigns, such as communicating with the customer or lobbying other stakeholder groups.

The decisions taken are documented using templates and provided to the market and control teams as hard data on which to base their decisions. In addition to these inputs, teams can present their offering to the market team (and everyone else in the market, e.g., competitor teams and the control team representing all other market participants).

This way, just as in the real world, at certain points of the simulation, all parties involved have the same level of information on which they base their next steps.

The market team assumes the role of customers, gauges the relative attractiveness of the various offerings by the company and competitor teams, provides feedback, and awards market shares.

The control team then consolidates the hard data (such as price points and investments) and the soft data, such as the market team/customers’ perception. It then calculates numbers such as the market’s overall size, segment sizes, segment shares, profit margins, etc.

Because time and resources are limited, quantitative feedback is restricted to include only key figures such as profit and loss statements, capital expense calculations, or key KPIs.

The feedback from the control team represents the starting point for each team’s next move. For example, a competitor team that “buys” market share by selling its products cheaply will gain market share but lose profitability. Thus, it may have limited funds in the next move.

Overview of activities in a typical move

Each move in business wargaming may take as much as a whole day.

The morning session typically starts with the company and competitor teams analyzing the data and additional information available, preparing their offerings and striking deals, filling out templates, and preparing their presentations for the plenary session around lunchtime.

In the afternoon and evening sessions, the market and control teams calculate the market shares and quantitative impact, while the company and competitor teams already start preparing for the next move.

They continue to do so after they get the results from the market and control teams and will adjust their preparation if necessary. Overnight, detailed results in the form of profit and loss statements and key data are calculated, and reports are prepared as a starting point for the following day’s session where the next move is planned.

When executing these moves, it is important that the teams remain separate and do not exchange information directly with each other. All communication with competitors, alliance partners, acquisition targets, etc., must be routed via email or other agreed-upon channels.

The control team can impose additional restrictions on a deal (e.g., anti-trust regulations), limit acquisitions to only parts of the business, or impose the obligation to sell other parts.

After all moves have been played out, a first assessment of the lessons learned is made. Inputs are gathered in a plenary session, where participants reflect on what worked well in their strategies and what did not.

This initial assessment is followed by a team of wargaming experts diving deeper into the data gathered through the simulation and evaluating other sources, such as email traffic. A consolidated report is presented about a week later to the sponsor of the game, including recommendations for adjustments to the initial strategy, if any.

Designing and Executing a Wargame

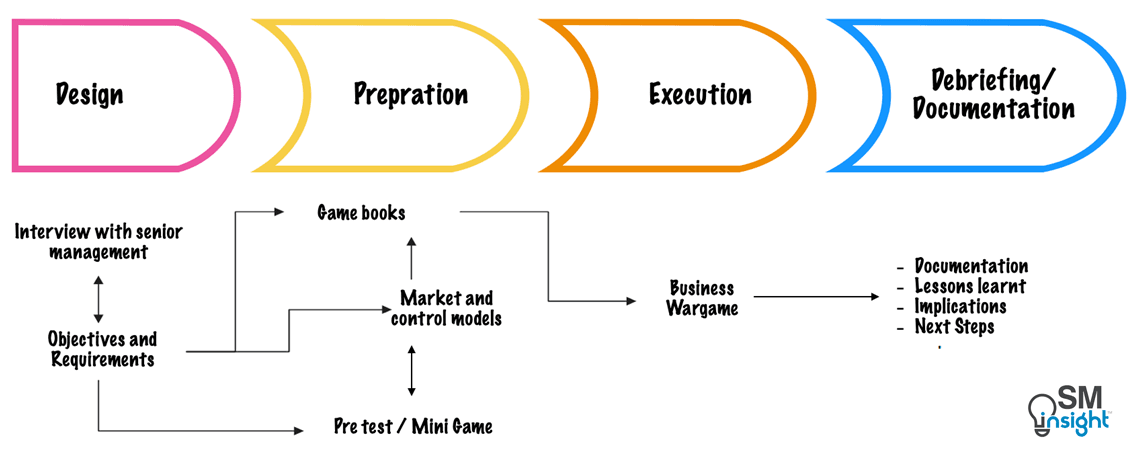

While the specifics of wargame design may vary significantly depending on the type of game and the underlying questions that need to be answered, typically, business wargaming follows a four-step process: design, preparation, execution, and debriefing/documentation:

Each of these steps includes a variety of sub-activities and takes about 8–12 weeks from preparation to conclusion.

Design Phase

The most important aspect of the design phase is determining the game’s objectives and distilling the critical questions to which the organization wants answers. Ideally, games should be commissioned by the CEO, a member of the board of directors, a division head, or a business unit manager.

Following are some key questions leadership must ask:

- What does the company want to learn from the business wargame?

- What are the key questions the wargame needs to answer?

- What are some of the most relevant and unaddressed issues in the organization?

- Who should participate in the process during the design and play stages?

- What is the focus of the game?

- What products, stakeholders, competitors, customer segments, and markets are most relevant to answer the questions?

- What should be the time horizon of the business wargame?

Answering these questions thoroughly and gaining a consensus view of the objectives is critical to success.

Preparation

This step involves gathering information about the main competitors, the market(s), customers, current and pending regulations, technology trends, etc. This information is then distilled into the gamebooks describing how to play the game and into the market and control models that provide objective measures.

Gamebooks contain information about the client company and its competitors, the market overview, the most critical industry trends, regulations, etc.

Market models are designed, considering key aspects, such as the main customer groups, essential financial data, etc. While important, market models are merely a support tool for the experts in the market and control teams, who must scrutinize their results in any event and, if necessary, adjust them to emphasize specific developments.

Once the basic model is in place, a “mini” game should be conducted to test the model’s sensitivities and detect and correct any bugs. The preparation phase provides the data set and rules for the game while ensuring that the game is focused on the relevant questions.

Regardless of their team, the participants must receive a proper briefing to get the most out of the game. This briefing, which can make up the last step of the preparation or the first step during the game’s execution, will set the common ground for all involved.

Execution

Execution is the fun part of any business wargame, typically involving three moves, as already discussed. Here, it is important that everyone involved gives their best, tries to live their assigned role, and sticks to the schedule and agreed deliverables.

Debriefing and documentation

A detailed debriefing occurs around a week after the game and is arguably the most important part of any business wargame.

Wargaming experts (consultants) compile the core results based on the coaches’ observations, participant inputs, hard data provided through models, and evaluation of all the email traffic throughout the moves.

This includes a list of the most important observations, lessons learned from the game, and consequences for the organization. Based on the deductive approach, a set of specific recommendations is prepared.

The depth and focus of the debriefing depend on the game’s objectives.

In a strategy testing game, for instance, the debriefing follows just the described path, while in a crisis prevention game, an action plan or contingency plan is developed. In educational games, the debriefing may focus more on the group dynamics and the key points in the decision process, such as where the group took quantum leaps or why mistakes were made.

Critical success factors for design and execution

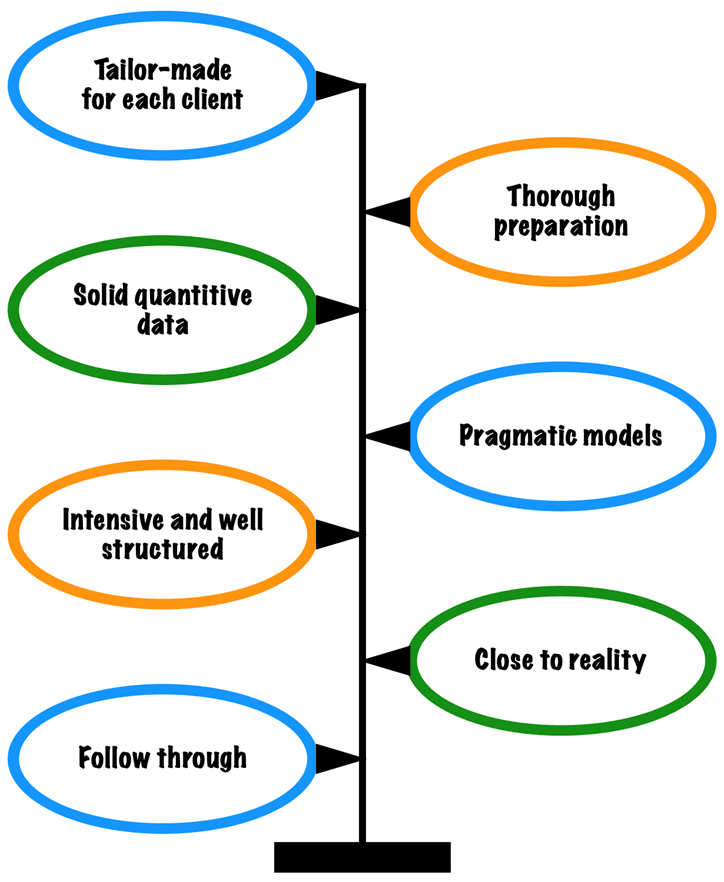

The following are the critical success factors for designing and executing a business wargame with success:

- Tailor-made for each client: business wargames must be tailored to reflect an organization’s overarching objective, issues, and questions.

- Thorough preparation is critical, and it starts with in-depth interviews with the principal players before the game. Once buy-in is obtained, thorough work must be done on the gamebook and models.

- Solid quantitative data: The game should have solid quantitative data. If this is not feasible, it should always provide a framework that allows reverse engineering to explain why certain things turned out the way they did.

- Pragmatic models: models must be comprehensive but focus on the key questions and reduce complexity rather than trying to model everything that is happening.

- Intensive and well structured: good wargames are intensive yet fun for the participants. They are tightly scheduled with clear deliverables and a professional team to run and coach the game. This way, participants can fully submerge into the experience and virtually live through likely futures.

- Close to reality: The better participants identify with their roles, the better the mutual learning experience. Facilitators must set the stage and ensure participants are motivated and well-prepared to take on their roles. They also need to stay on top of all the actions and keep the participants within the boundaries of reality.

- Follow through: each wargame must have a proper debrief covering the action plans and lessons learned. Without them, wargames are of little use.

Where Wargaming Works Best

Wargaming in business is most effective in the following situations [2]:

- The industry in question has a competitive dynamic in which players are affected by each other’s actions.

For example, suppose Company A introduces a product that competes with Company B. In that case, B may react by cutting its price, while another competitor, C, might drop out of the industry. A, in turn, might respond to the price cut with a service increase. - The market reaction is partly or wholly unpredictable because of rapid change, the introduction of new technologies, shifts in market demands, etc., none of which could be forecast with a deterministic model.

In the above example, customers must first react to the product introduction, then the price cut, and finally, the combination of the two and the service increase. Customers of the company that quit the field will also have to choose among the remaining players. - The problem is examined dynamically over time (e.g., several years). This improves the validity of the answers provided by the wargaming exercise.

Assumptions about customer behavior today are largely irrelevant once a new product is introduced, a price cut or service increase has been made, and one or more players have exited.

After all, companies are concerned not only about the current (for example, the product introduction) but also about sustaining profits for the long-term. - The problem has too many unknowns to prevent a straightforward, quantitative solution. There are too many dimensions of the problem to consider, and it is impossible to capture the interactions among all of these.

For example, modeling and predicting the reactions of multiple competitors, the marketplace, regulators, and other participants.

In such situations, typical analysis-intensive strategic planning does not work because it only interprets the past and suggests how the future might evolve if there is little change from the past.

Such assumptions are self-defeating as the past never really repeats itself. Thus, the analysis cannot predict how competitors will behave when faced with new challenges.

Scenario planning, which uses historical analysis to plot future outcomes, can also be deceptive under these conditions. Because scenarios are simply a best guess at the future, tempered by informed judgment as to how trends may play out over time, it is easy to believe that the future plays according to our own set of biases. The error is also compounded by the absence of any way of predicting when discontinuities might occur or their impact on the competitive environment.

Key questions to ask before you play a business wargame

Many companies don’t learn as much from war games for various reasons. Some misjudge when they are appropriate, some fail by not including the right participants, yet others rely on standardized game design software or apply the same approach to operational problems they previously used for strategic or organizational ones.

Senior executives must ask tough questions when contemplating war games or answering proposals to use them. McKinsey and Company suggest four questions that can significantly increase the chances that a wargaming exercise will improve real-world decision-making [6]:

1. Can a war game help with our problem?

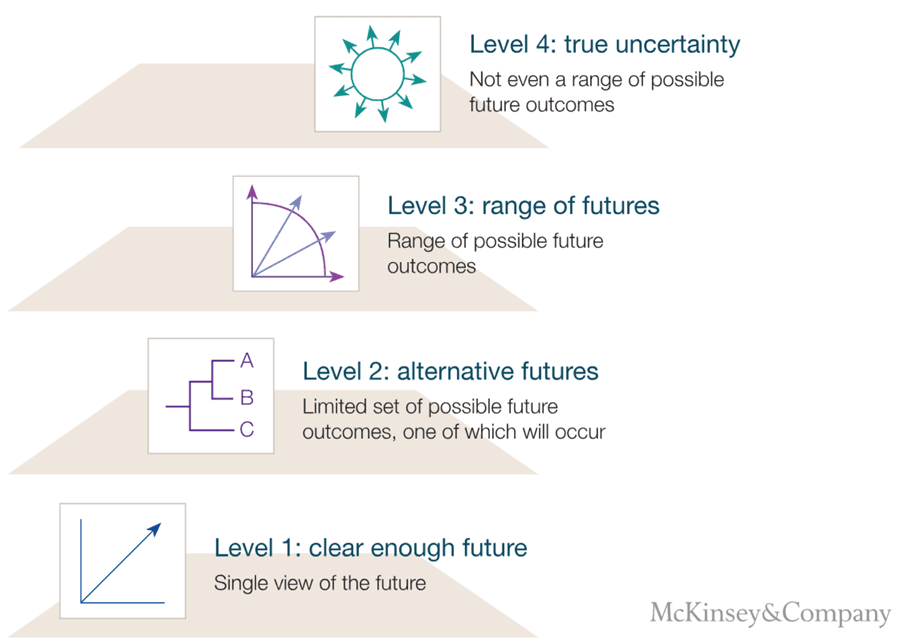

Business wargames work best in situations with moderate levels of uncertainty, typically suited for Level 2 and Level 3 uncertainties, as shown in the figure:

If the uncertainty is too great (For example, the impact of robotic nanotechnology on manufacturing), game planners can’t offer enough guidance to make reasoned decisions.

Wargaming is most effective when two or three outcomes seem plausible along each available dimension. When no amount of analysis will provide the right answer, wargaming results can illuminate the range of possibilities to consider.

2. What kind of game to play?

Wargames are most valuable when a company and its competitors have few but discrete choices and responses to test. For example, a company deciding whether to raise prices by 5% or keep them constant may want to know how its biggest competitor might respond.

Given the tactical objective, the company could conduct two games: one in which prices are increased and another in which they aren’t. Alternatively, it could also conduct a game where it raises prices by 5% while making other adjustments, such as increasing marketing spend. The key is to visit all potential choices and ensure each is tested.

Tactical wargames, however, are not suitable in all situations. When companies must answer more strategic questions, such as a defense company looking to win market share, given the increasing budget pressures on the Government, a different approach is needed.

The company may use “levers” such as pricing, contracting, operational improvements, and partnerships in such cases. The outcome isn’t a tactical playbook—a list of things to execute and monitor—but strategic guidance on the industry’s direction, the most promising types of moves, the company’s competitive strengths and weaknesses, and where to focus further analysis.

3. Who will design and play the game?

Who designs the game and who plays depends on whether the game’s objective is tactical, strategic, or the creation of organizational alignment.

Tactical games, with detailed moves and evaluation criteria, are relatively straightforward and require leaders with deep expertise and decision-makers as their critical input sources. Such wargames (e.g., as a pricing game) can have a relatively small set of participants.

A strategy wargame, in contrast, requires much broader participation to avoid being overly influenced by the hypothesis of a few.

Alternatively, if the goal is organizational alignment around a strategic decision, it is best to include leaders of all functions. It is also worth including frontline employees since they can bring different viewpoints.

In general, having a diverse set of participants creates valuable opportunities to broaden their understanding of the industry. For instance, employees assigned to teams with less familiar roles can gain new perspectives from the experience.

These shared experiences, which would have been impossible with a smaller or homogenous group of participants, can stimulate discussions across the company as market conditions evolve.

4. How often should wargames be played?

Most wargames are played as one-off games, as running a game repeatedly to test the same uncertainties with the same participants is usually pointless.

Repeating can be beneficial when the goal is organizational alignment. Through wargames, people can develop shared experiences that make them more likely to embrace change. People who didn’t experience the first game, such as the broader group of employees who would implement the decision, could learn better by doing.

Repeating wargames can also be useful when conditions change. For example, it may be time to rerun a strategic game if competitors or technologies have significantly evolved.

Tactical games like those for pricing negotiations can be repeated frequently (every three or four months) with the same set of players and slight modifications to reflect changes in the market. This helps salespeople refine their pitches as customer needs, competitive offerings, regulations, and other factors shift.

Some situations may call for repeated play—for example, a necessary negotiation where a firm has little room to maneuver and must find its optimum strategy.

Business Wargaming And Strategy

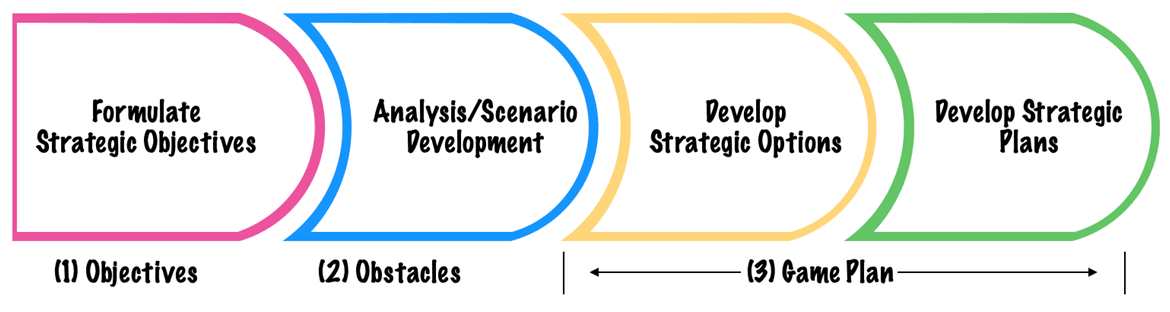

An organization’s strategy deals with three main questions:

(1) What objective or vision does it want to achieve?

(2) What needs to be done to reach that objective? (game plan for execution)

(3) What obstacles may get in the way, and what can be done about them?

Business wargaming primarily deals with question (3), where the answer should identify obstacles, not only within the company but also from competitors and the larger environment, such as legislation, stakeholder groups, technology, and so on.

Most organizations follow a linear approach to strategy formulation, moving from question (1) to (3) with the assumption that after analyzing all data and collecting available information, the plan is the single best answer and, thus, the course of action to achieve the objective.

While this strategic planning process is an excellent way to understand past trends and allow extrapolation of these trends into likely future developments, it is certainly not foolproof.

Some organizations try to address this limitation by using scenario planning to identify trends and key uncertainties and combining them in future pictures to discover the boundaries of potential outcomes.

This helps improve decision-making by generating alternatives, assigning probabilities to expected future outcomes, formulating a comprehensive and cohesive strategy, and, ideally, contingency plans.

Even with all these advantages, scenario planning is still limited by the fundamentally biased views of the people who developed it and the limits of their imagination. Depending on the approach taken, scenarios can be rational and safe extensions of the past and often classify likely outcomes along simple linear views of reality.

The real world, in contrast, involves complexity and multiple dimensions.

This is where business wargaming is more effective in testing the strategic plan for its robustness under close to real-life conditions. It significantly improves the outcome and reliability of the final strategic plan. It also involves the participants, fosters organizational learning, and challenges the mental models of those involved.

Overall, applying business wargaming in strategy formulation helps:

- Actively involve all participants.

- Anticipate future developments using the simulation.

- Include multiple perspectives.

- Provide multiple ways of learning.

- Have team-building effects.

- Provide a dynamic simulation.

Other Applications Of Business Wargaming

Crisis management

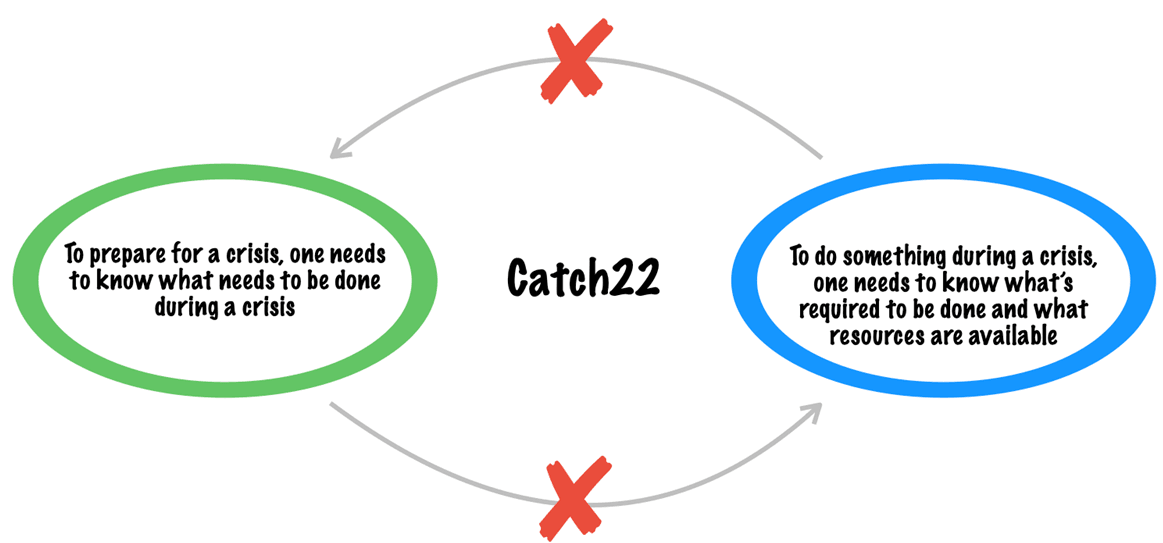

Crises are an inevitable, natural feature of the business environment and are no longer aberrant, rare, random, or peripheral.

The challenge in dealing with crises is that organizations cannot fully understand what needs to be done during a crisis unless they first know what they need to do and have before a crisis. At the same time, they cannot understand what they need to do beforehand unless they know what they will be required to do during a crisis.

(Source: Business Wargaming Daniel Oriesek [3])

Wargaming helps break this Catch22 situation by allowing participants to experience how they or their organization are prepared to deal with crises.

A crisis occurs when the links between organizations, people, and technologies break. The value of using wargames to prepare for a crisis lies in better understanding complex systems, identifying critical points, and determining what other problems may cause or exacerbate a potential crisis.

Wargaming also allows for scenario testing, not only those that are likely but also those that people might not have thought of yet. Preparing for the expected but, more importantly, for the unexpected is the key objective when wargaming for crisis response preparation.

Developing Foresight

An organization’s success depends on reaching the desired future before its competitors do. Foresight is about spotting developments before they become trends, seeing patterns before they fully emerge and grasp the relevant features of social currents.

In short, foresight is about recognizing weak signals of change in the corporate business environment, imagining alternative scenarios, and predicting how one’s own organization is likely to evolve within them.

As a tool, business wargaming helps develop foresight, recognize predictable surprises, and spot weak signals of change, especially when designed to project several years into the future.

It forces participants to think ahead, critically review their assumptions about tomorrow, and question their mental models analytically and participatively. Cognitive flaws or defense mechanisms are more likely to be recognized in a participative wargaming exercise that allows managers to experience future events.

Change management

Business wargaming is a powerful change management tool because it brings a group of people together and has them work jointly on a common challenge. The insights they gain and the increased understanding of the other participants’ views initiate the change process.

Any change within an organization will face resistance. The roots of this resistance can be found in fear and a survival instinct, which operate at several levels to protect social systems from painful experiences of loss, distress, chaos, and the emotions associated with change.

Introducing a business wargame before a change program enables participants to test how the change process may evolve, particularly which obstacles to change may emerge. This enables them to anticipate and counter obstacles and face their fears.

Education and Recruiting

There are several benefits of applying wargaming in management education, including:

- Orienting and training new employees: wargames allow new hires to gain decision-making experience in the new company.

- Screen current managers or would-be managers: wargame provides great opportunities for skill assessment. In the hiring process, for example, they can be used to test analytical or decision-making skills.

- Ongoing management training: applying business wargaming in management development allows executives to work on their decision skills, experiment with strategies, learn analytical tools, identify areas for training, and gain insights into their organizations, competitors, and other stakeholders.

In summary, when done well, business wargames benefit participants and companies greatly by providing unique opportunities to “witness” likely futures through shared experiences.

Sources

1. “BBN Times”. Thomas Schelling: A Person Cannot Draw Up A List Of Things That Would Never Occur To Him, https://www.bbntimes.com/global-economy/thomas-schelling-a-person-cannot-draw-up-a-list-of-things-that-would-never-occur-to-him. Accessed 21 Mar 2025.

2. “Dynamic Competitive Simulation: Wargaming as a Strategic Tool.” PWC, https://www.strategy-business.com/article/15052. Accessed 21 Mar 2025.

3. “Business Wargaming: Securing Corporate Value”. Daniel F. Oriesek, https://www.amazon.com/dp/B01JO2DASS. Accessed 21 Mar 2025.

4. ” Business games–play one!”. Gerhard R. Andlinger, https://search.worldcat.org/title/Business-games-play-one!/oclc/5813563. Accessed 21 Mar 2025.

5. “WARGAMING AND STRATEGIC SIMULATIONS”. Booz Allen Hamilton, https://www.boozallen.com/markets/commercial-solutions/wargaming-and-strategic-simulations.html. Accessed 28 Mar 2025.

6. “Playing war games to win.” McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/playing-war-games-to-win. Accessed 24 Mar 2025.

7. “Strategy under uncertainty”. McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/strategy-under-uncertainty. Accessed 24 Mar 2025.