What is the Triple Bottom Line

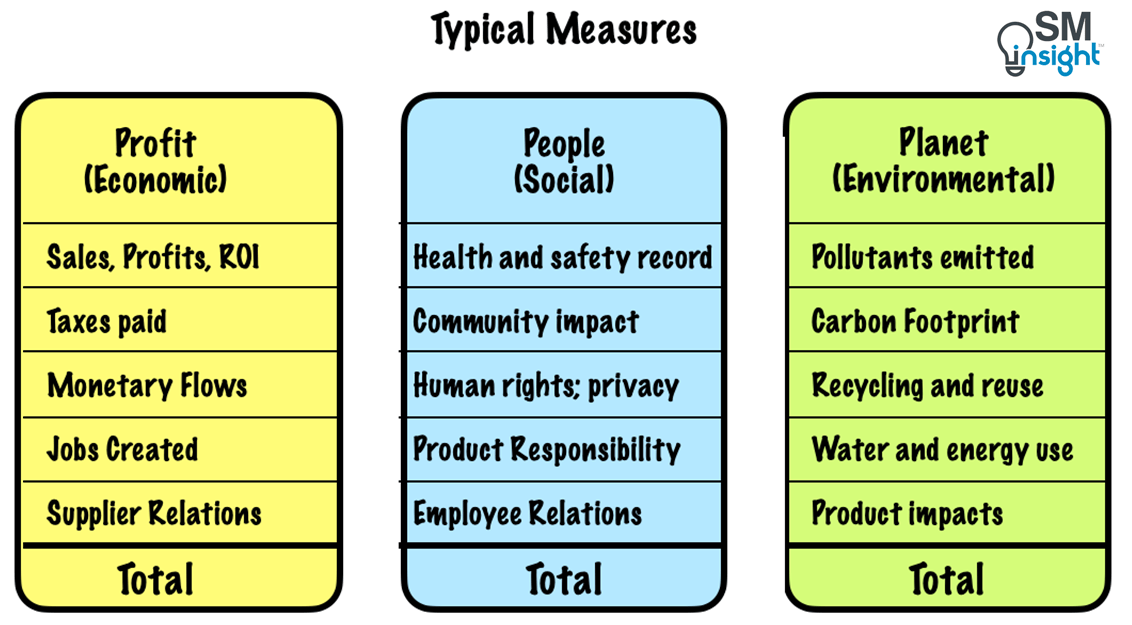

Triple Bottom Line (TBL) is a framework for measuring and reporting corporate performance against Economic, Social, and Environmental parameters.

It consists of three Ps: Profit, People and Planet.

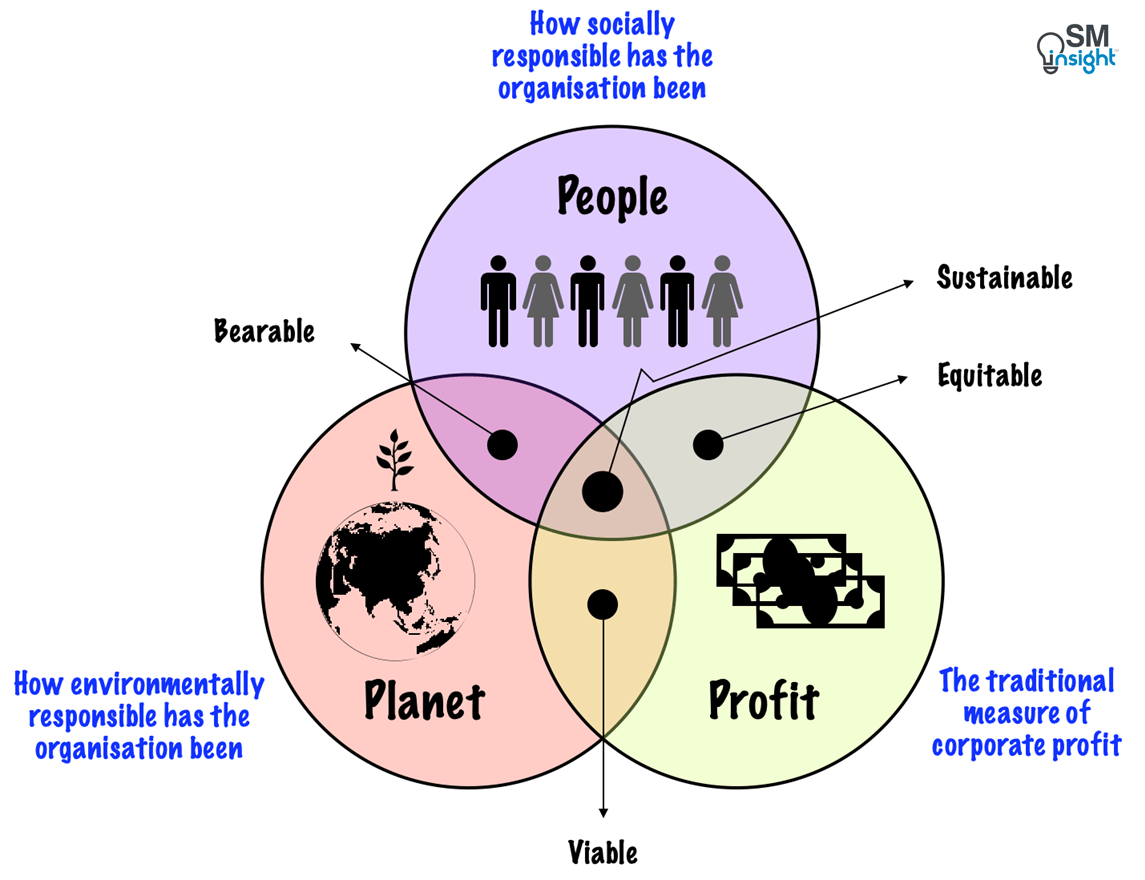

First is the traditional measure of corporate profit – the “bottom line” of the Profit and loss account.

The second is the bottom line of a company’s “People account” – a measure in some shape or form of how socially responsible an organization has been throughout its operations.

The third is the bottom line of the company’s “Planet” account – a measure of how environmentally responsible, the company has been.

The phrase “Triple Bottom Line” was first coined in 1994 by John Elkington[2], the founder of a British consultancy called Sustainability and a well-known figure in the field of sustainability and social entrepreneurship.

Interest in TBL accounting has since been growing across the board including for-profit, nonprofit and government.

TBL, CSR, ESG, Sustainability, and the Green Movement

TBL is closely linked to concepts like Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Environment Social and Governance (ESG), Sustainability, and the Green Movement and is sometimes interchangeably used.

While broadly similar, these concepts have subtle differences:

CSR is a component of the Social aspect of the Triple Bottom Line. It falls under the Social dimension, as it pertains to a company’s ethical and social actions, which align with the “people” aspect of the TBL.

ESG, like TBL, assesses a company’s performance in three areas, with Environmental and Social being two of them. Both emphasize the importance of considering social and environmental factors alongside economic ones to achieve long-term sustainability.

Sustainability: TBL is essentially a framework for achieving sustainability. Sustainability aims to balance economic, social, and environmental concerns to ensure the well-being of present and future generations. TBL provides a structured approach to assessing and promoting sustainability by measuring and managing performance in all three dimensions.

Green Movement: The Green Movement’s goals align with the environmental aspect of the Triple Bottom Line. The Green Movement’s efforts to promote environmental conservation and awareness contribute to the broader goal of achieving a sustainable world, as envisioned by the TBL.

Relevance of Triple Bottom Line

The once-prevailing notion of a world with limitless resources has been deeply challenged and reversed over time. Recent decades have witnessed a series of events and trends that have emphasized the interconnectedness and the delicate nature of the shared global environment.

Growing emission gaps amidst rising sea levels and catastrophic natural disasters have forced stakeholders to demand responsible business practices from companies.

Companies are forced to think more broadly about how they make money, and about the impacts their operations and decisions have on the environment and society.

For a long time, the TBL approach was seen as idealistic in a world that emphasized profit over purpose.

Today, proponents of sustainability including investors, consumers, regulators, NGOs, and others insist that companies address a range of nonfinancial factors, from climate change to demographic trends to product labeling.

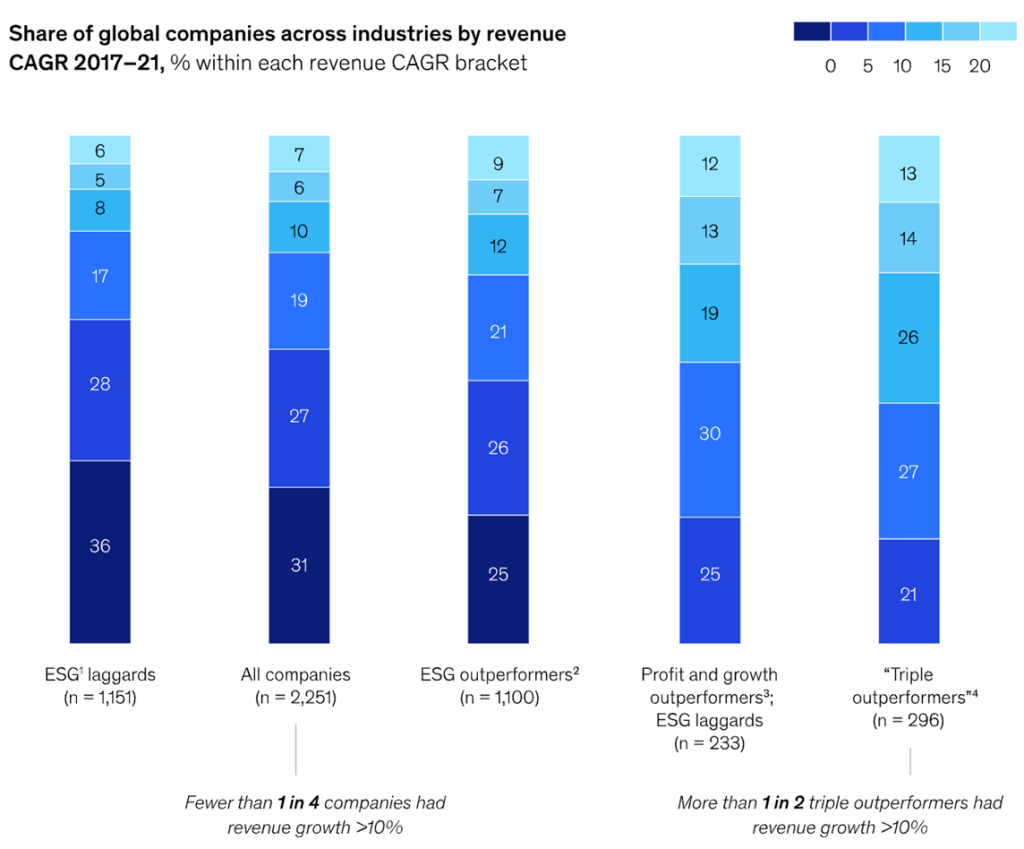

Contrary to popular notion, however, TBL doesn’t inherently value societal and environmental impact at the expense of financial profitability. Many firms have reaped financial benefits by committing to sustainable business practices.

A McKinsey & Company analysis in 2023 revealed that financially successful companies that integrated the environmental, social, and corporate governance priorities into their growth strategies outperformed their peers.[3]

Understanding the three Ps

Firms implementing TBL use the “three P’s” as categories to conceptualize their environmental responsibility and determine any negative social impacts to which they might be contributing.

Together, the 3Ps integrate sustainable practices into every facet of business operations, including supply chains, business partners, and renewable energy usage to positively impact society and the environment in addition to turning a profit.

Profits

In a capitalist economy, a firm’s success most heavily depends on its financial performance or the profit it generates for shareholders. Most companies’ key business decisions are carefully designed to maximize profits while reducing costs and mitigating risk.

A focus on profits is often presented as a short-term perspective and one that is either necessary or immoral, depending on the point of view. However, TBL’s concept of ‘enlightened capitalism’ rests on the twin ideas that:

- Profits can be maximized if the best possible social and environmental performances are produced.

- Profit maximization over the longer term does not necessarily require profit maximization over the short term.

Profit is also the easiest component of the TBL to report with strong systems and guiding regulations in place.

People

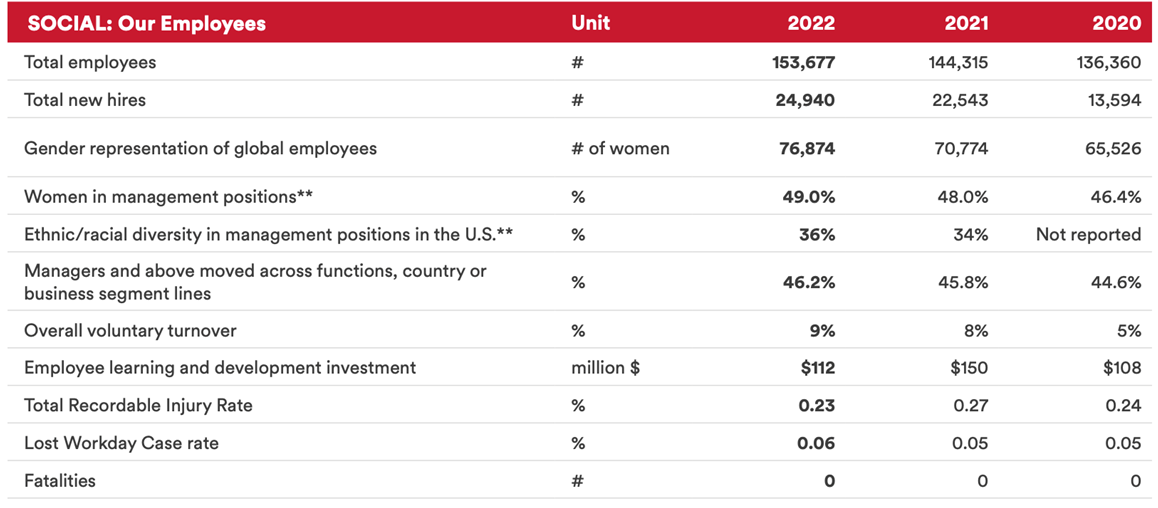

The ‘People’ bottom line measures businesses’ impact on human capital and may contain financial as well as nonfinancial measurements.

While some of the metrics in this area are stipulated by Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or other reporting rules, responsible companies voluntarily report additional metrics (based on internally sourced data) that go beyond mandatory requirements.

Examples of measurements of people include:

- Average employee payroll to demonstrate livable wages exceed local expectations

- Average benefits per employee to demonstrate the full benefit package per worker

- Vacation hours and policies to show the importance of work-life balance

- Demographics such as age, race, sexual orientation, or religious groups that bring out diversity. (Some of these metrics may require employee consent as per law)

- Vendor demographics such as identifying small businesses, LGBTQ-owned, Veteran-owned, or minority-owned.

People metric recognizes the interdependency of all the human relationships and interactions that enable the company to operate.

It is about offering equal opportunities for professional or educational advancement, creating a safe work environment, and engaging in fair labor practices.

Planet

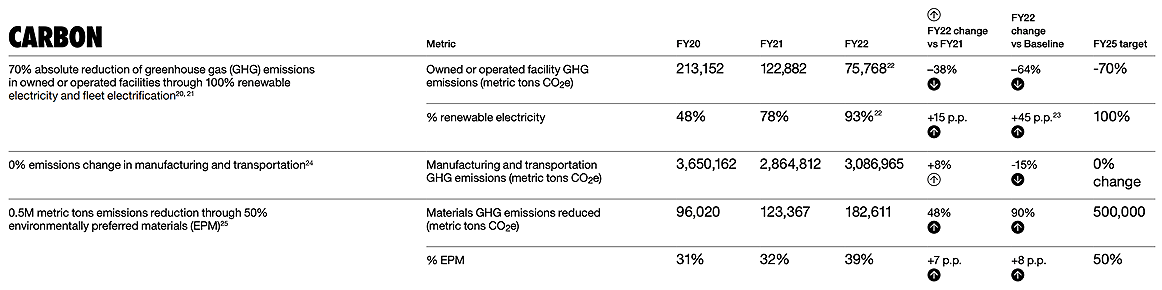

‘Planet’ is the most difficult TBL component to measure and requires expertise and effort. Common environmental reporting used by companies include:

- Reduction trends in greenhouse gas emissions through the adoption of new technologies

- Amount of waste generated

- Number of products recycled

- Fossil fuel consumption and energy consumption per unit of production

- Proportion of raw materials sourced ethically

A full environmental report can be approximated by recording all inflows, outflows and leakages and thus capturing most, if not all environmental interactions. Coupled with the organizations’ ecological footprints, this provides a substantial picture of the organization’s environmental stewardship.

Thus, the 3Ps of TBL, in an over-simplified representation can be put together as shown:

While there are well-established guidelines for reporting profits, there is still no clear way of describing the environmental benefits accurately and completely or putting a number to the social benefits. Some of the numbers themselves require a great deal of explanation, which is why most financial reports include pages of management discussion and analysis.

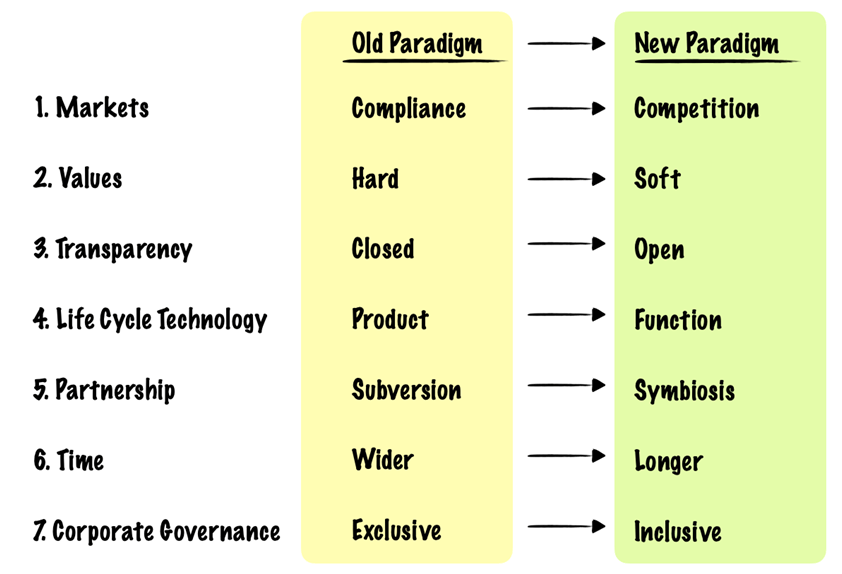

Revolutions that will shape TBL

There are seven closely linked revolutions that will drive the transition of companies from traditional capitalism to sustainable capitalism and, hence, toward TBL. These seven shifts are as shown:

Markets

Going forward, businesses will operate in markets that are more open to competition, both domestic and international. Growing numbers of companies will find themselves challenged by customers and shareholders about aspects of their TBL commitments and performance.

As a result, companies will be compelled to shift their perspective on TBL, transitioning from a compliance-centric stance to viewing it as a competitive determinant.

Values

When values change, companies that once stood on solid ground for decades suddenly find their markets turned upside down and inside out. And such a change is inevitable with every succeeding generation.

For example, in 2022, the Norway Wealth Fund which traditionally depended on Oil and Gas companies for returns decided to consider the environmental impact of its investments. The $1.2 trillion fund now mandates companies in which it invests to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.[8]

The world’s largest fund has since been steadily upping the pressure on Oil and Gas companies in its portfolio for not doing enough to cut emissions.

Transparency

New value systems coupled with radically different information technologies, such as the internet and social media, have led to the collapse of many forms of traditional authority.

A wide range of different stakeholders increasingly demand information on what businesses are doing and planning to do. Increasingly, too, they are using that information to compare, benchmark and rank the performance of competing companies.

For example, a few decades ago, people did not care what restaurants and fast-food joints put into their food. They didn’t know where a company’s products came from. And they certainly didn’t know the values and beliefs of a company’s CEO.

Fast forward to today, customers expect to know a lot more. A fast-food chain like McDonald’s needs to disclose the ingredients, calories, nutritional value and even the farms from which it sources food. The company also makes its values and mission abundantly clear on its website.

Transparency extends not just to businesses but also to countries. For example, The United Nations ranks its member countries based on the progress of their Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

![Top 10 countries in terms of progress towards achieving the 17 SDGs set by the United Nations[10]](https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/wp-content/uploads/countries-17-SDGs.png)

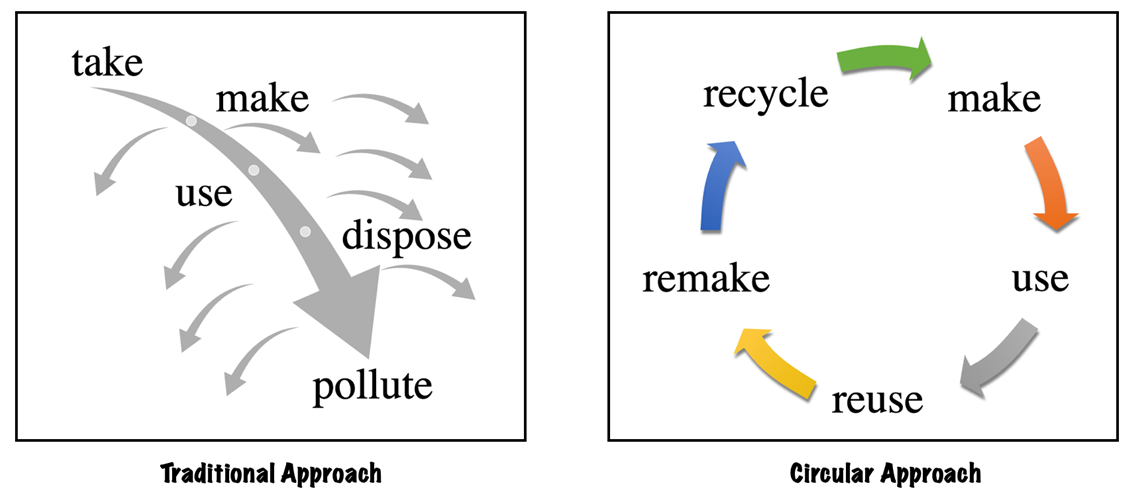

Life-cycle technology

With the transparency revolution, companies are increasingly being challenged on the TBL implications of their products even after their useful life has ended.

There is a shift in focus from the acceptability of products at the point of sale to emphasis on their performance and impact from cradle to grave.

For example, US sporting goods giant Nike now operates with a long-term focus on developing a truly circular system where waste becomes the main source for new materials and the manufacturing process itself creates zero carbon emissions.[11]

Partnership

Companies are realizing the limitations of their individual power and the need for partnerships to drive transformational change in sustainability.

Rather than going in separate directions, like-minded companies, each with strong R&D resources, are coming together to work towards developing technology at a faster, more effective pace that is mutually beneficial.

For example, Coca-Cola, Ford Motor Co., H.J. Heinz, Nike, and Procter & Gamble joined forces to accelerate the development and use of 100% plant-based PET materials in their products.[12]

Time

The sustainability agenda will promote a profound shift in the way companies understand and manage time. On the one hand, time is becoming ‘wider’ with more and more happening every minute of every day, on the other, sustainability is forcing companies to think long-term.

All overnight success takes about 10 years

Jeff Bezos

With the increasing pace of competition, the need to build a stronger ‘long time’ dimension to business thinking and planning has become ever more pressing. The use of scenarios, or alternative visions of the future is one way in which companies can expand their time horizons and spur creativity.

Corporate governance

The centre of gravity of the sustainable business debate is shifting from public relations to

competitive advantage and corporate governance. After all, the business end of the TBL agenda is the responsibility of the corporate board.

Company boards find themselves answerable to new-age questions such as:

- What is business for?

- Who should have a say in how companies are run?

- What is the appropriate balance between shareholders and other stakeholders?

- And what balance should be struck at the level of the triple bottom line?

The better the system of corporate governance, the greater the chance that companies can be built on genuinely sustainable capitalism.

Motivations for implementing TBL

Companies implementing TBL can explore the potential value creation by evaluating the benefits in five ways:

Top-line growth

Companies that implement TBL are seen as responsible corporate citizens. Stakeholders ranging from customers to governing authorities are more likely to trust such companies and award access, approvals, and licenses that afford fresh opportunities for growth.

Such companies find it easier to expand into existing as well as new markets or serve new customers.

The Global Sustainability Study 2021 by Simon-Kucher & Partners[13] found that more than a third of global consumers are willing to pay more for sustainability as demand grows for environmentally friendly alternatives.

Governments around the world are also gearing up. For example, the US government will soon require its contractors to meet sustainability regulations.[14]

Many companies have transformed entire business models around sustainability.

Finland’s Neste, for example, started out in 1948 as an oil refining company and today derives almost 40% of its revenues from clean energy. The company’s share of clean Investments was at 88.3% in 2022.[15]

As a global leader in renewable and circular solutions, Neste has ranked among the 100 most sustainable companies in the world for the 17th consecutive time.[16]

Cost Reductions

For companies implementing TBL, there are financial benefits to unlock no matter where a business exists and operates.

New and tightening regulations across the world require enterprises to meet their ESG targets and to measure and report them. Without ESG metrics in place, businesses can run into the risks of legal costs, fines, penalties, and reputational damage.

Many sustainability initiatives can reduce costs even as they drive ESG goals.

For example, the price of clean sources of energy has reached or surpassed price parity with fossil fuel-based energy.[17] Many countries are encouraging the transition to clean energy through tax exemptions and benefits.

Most sustainability initiatives do not require huge capital investments. Businesses also enjoy access to cheaper capital from Investors who value sustainability. A 2020 survey by Gartner Research found that 85% of investors considered ESG factors in their investments.[18]

Many companies are realizing huge savings by implementing TBL goals. United Airlines, for example, saved over $2 billion by making its planes lighter to save fuel. Clarion Hotels saves about $17,250 a year by cutting down the use of water.[20]

Reduced regulatory and legal interventions

Companies with good sustainability image enjoy stronger external-value propositions enabling them to achieve greater strategic freedom and lower regulatory pressure. Such companies have a lower risk of adverse government action.

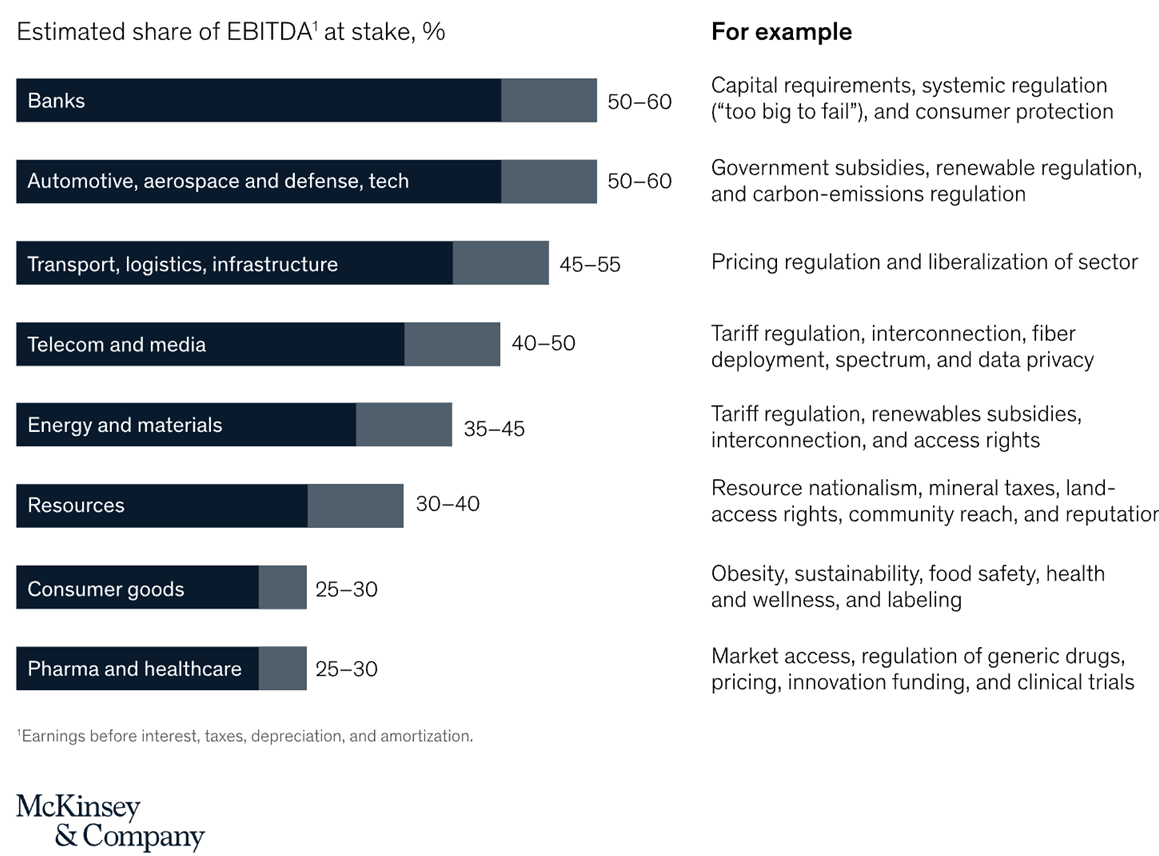

A study by McKinsey and Company found that typically one-third of corporate profits are at risk from state intervention. The impact varies by industry and can range from 25 to 30 percent in the case of pharmaceuticals and healthcare to 50 to 60 percent in the case of Banking:

Better employee productivity

Companies with a strong ESG proposition find it easier to hire talent as more and more job seekers are choosing organizations that share their environmental and social values.[19]

Such companies retain quality employees, enhance employee motivation by instilling a sense of purpose, and increase overall productivity.

Research has shown that employee satisfaction is positively correlated with shareholder returns[22] and that employees with a sense not just of satisfaction but also of connection perform better.

The stronger an employee’s perception of impact on the beneficiaries of their work, the greater the employee’s motivation to be positive and helpful and promote social acceptance and friendship.

Conversely, a weaker ESG proposition can drag productivity down leading to strikes, worker slowdowns, and other labor actions. Sometimes, such productivity constraints can also manifest outside a company’s bounds, across the supply chain.

Farsighted companies have realized the importance and paid heed. Nike for example, started its sustainability initiatives around 1996 and set up a department tasked solely with improving the lives of factory workers.[23]

Investment and asset optimization

Companies that take TBL seriously can enhance investment returns by allocating capital to promising and more sustainable opportunities. It can also help companies avoid investments that may not pay off because of longer-term environmental issues.

A robust ESG strategy in investing guides capital towards sustainable opportunities and minimizes the risk associated with stranded investments. Conversely, neglecting ESG can erode cash flows.

For example, Tesla is clearly a leader in the electric vehicles space, but at its core, the company is about accelerating the world’s transition to sustainability.

That vision has guided Tesla’s move as it poured billions of dollars into its Gigafactories and supercharger networks. In contrast, Volkswagen, still reeling from its auto-emission scandal did little to capitalize on the EV opportunity.

Challenges and Limitations

2019 marked the 25th anniversary of TBL since John Elkington coined the term but it was also the year in which the author proposed a “strategic recall” stating that the concept needed more fine-tuning and that its practical impact was limited.[24]

Elkington pointed to some of the fundamental limitations of TBL:

- Business leaders are hard-wired to ensure that they hit their profit targets, but the same has rarely been true of their people and planet targets.

- TBL wasn’t designed to be just an accounting tool. It was supposed to provoke deeper thinking about capitalism and its future, but many early adopters used the concept as a balancing act, adopting a trade-off mentality.

- While thousands of TBL reports are produced annually, it has failed to genuinely help decision-makers and policymakers to track, understand, and manage the systemic effects of human activity.

Then there is the challenge of Greenwashing: a form of advertising or marketing spin in which companies deceptively use green PR and green marketing to persuade the public that an organization’s products, aims and policies are environmentally friendly.

Reputed global corporations have been involved in falsely claiming that their products and actions were environment/people friendly. Some of the examples include:

Volkswagen: Cheated emissions tests using a device that could detect and selectively reduce emissions levels. In real-world conditions, some of the pollutants were found to be 40 times the limit. During the same period, Volkswagen promoted low-emissions and eco-friendly features of its vehicles in marketing campaigns.[25]

BP: The fossil fuel giant adopted a green sunburst logo and changed its name to ‘Beyond Petroleum’. It added solar panels to its gas stations and misled the public with adverts that focused on low-carbon energy products while continuing to allocate more than 96% of its annual spending to Oil and Gas.[26]

ExxonMobil: ExxonMobil has not set a company-wide net-zero emissions target consistent with the Paris Agreement temperature goals. The company’s 2025 targets have been rejected as falling far short of the Paris goals and woefully inadequate for ignoring the vast majority of its climate impacts in the form of its Scope 3 emissions.[27]

Likewise, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and Nestle have consistently been the world’s top plastic-polluting corporations while speaking about sustainability and recycling.[25]

Adding to the above is the challenge of converting (and comparing) environmental and social bottom lines in terms of monetary values and balancing consumer preferences.

For example, one cannot say that a human life is worth more than the preservation of a scenic view, or that the lives of wild animals are more valuable than the maintenance of indigenous hunting cultures.

To what extent do these types of trade-offs across the triple bottom line make sense from a sustainability perspective remains a crucial yet unresolved issue.

Sources

1. “Youth entrepreneurial projects for the sustainable development of global community: evidence from Enactus program”. Anastasiia Dalibozhko and Inna Krakovetskaya, https://www.shs-conferences.org/articles/shsconf/abs/2018/18/shsconf_infoglob2018_01009/shsconf_infoglob2018_01009.html. Accessed 28 Aug 2023

2. “John Elkington (business author)”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Elkington_(business_author). Accessed 28 Aug 2023

3. “The triple play: Growth, profit, and sustainability”. McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-triple-play-growth-profit-and-sustainability. Accessed 28 Aug 2023

4. “2022 ESG Summary”. Johnson & Johnson, https://healthforhumanityreport.jnj.com/2022/_assets/downloads/esg-summary.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2023

5. “FY22 NIKE, Inc. Impact Report”. Nike, https://about.nike.com/en/newsroom/reports/fy22-nike-inc-impact-report. Accessed 29 Aug 2023

6. “The Triple Bottom Line: How Today’s Best-Run Companies Are Achieving Economic, Social and Environmental Success – and How You Can Too, Revised and Updated”. Andrew Savitz, https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/the-triple-bottom/9781118226223/. Accessed 29 Aug 2023

7. “The Triple Bottom Line: Does it All Add Up?”. Adrian Henriques and Julie Richardson, https://books.google.co.in/books?id=JIiHcXcLSHAC&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Accessed 30 Aug 2023

8. “Norway Wealth Fund Sets Net-Zero Target for Portfolio Firms”. Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-09-20/norway-wealth-fund-sets-2050-net-zero-target-for-portfolio-firms#xj4y7vzkg. Accessed 30 Aug 2023

9. “Hamburger”. Mcdonalds, https://www.mcdonalds.com/gb/en-gb/product/hamburger.html. Accessed 31 Aug 2023

10. “The overall performance of all 193 UN Member States”. United Nations, https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/rankings. Accessed 30 Aug 2023

11. “About Circularity”. Nike, https://www.nikecirculardesign.com/about/. Accessed 30 Aug 2023

12. “Five major U.S. brands collaborating on plant-based PET”. Plasticstoday, https://www.plasticstoday.com/five-major-us-brands-collaborating-plant-based-pet. Accessed 30 Aug 2023

13. “Recent Study Reveals More Than a Third of Global Consumers Are Willing to Pay More for Sustainability as Demand Grows for Environmentally-Friendly Alternatives”. Business Wire, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20211014005090/en/Recent-Study-Reveals-More-Than-a-Third-of-Global-Consumers-Are-Willing-to-Pay-More-for-Sustainability-as-Demand-Grows-for-Environmentally-Friendly-Alternatives. Accessed 31 Aug 2023

14. “Is Sustainability Becoming Part of Government Contracting?”. Aprio, https://www.aprio.com/is-sustainability-becoming-part-of-government-contracting/. Accessed 31 Aug 2023

15. “Neste’s annual reports”. Neste, https://www.neste.com/for-media/material/annual-reports. Accessed 31 Aug 2023

16. “Neste among the 100 most sustainable companies in the world for the 17th consecutive time”. Neste, https://www.neste.com/releases-and-news/sustainability/neste-among-100-most-sustainable-companies-world-17th-consecutive-time. Accessed 31 Aug 2023

17. “Renewable Power Remains Cost-Competitive amid Fossil Fuel Crisis”. Irena.org, https://www.irena.org/news/pressreleases/2022/Jul/Renewable-Power-Remains-Cost-Competitive-amid-Fossil-Fuel-Crisis. Accessed 31 Aug 2023

18. “The ESG Imperative: 7 Factors for Finance Leaders to Consider”. Gartner, https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/the-esg-imperative-7-factors-for-finance-leaders-to-consider. Accessed 31 Aug 2023

19. “How Nestle, Google and other businesses profit by going green”. LA Times, https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2019-09-20/how-businesses-profit-from-environmentalism. Accessed 01 Sep 2023

20. “Five ways that ESG creates value”. McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/five-ways-that-esg-creates-value. Accessed 01 Sep 2023

21. “For Employee Experience and Retention, Address Sociopolitical Issues”. Gartner, https://www.gartner.com/en/articles/why-engaging-with-social-and-political-issues-is-a-non-negotiable-for-your-employee-value-proposition. Accessed 31 Aug 2023

22. “Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices”. Alex Edmans, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, http://faculty.london.edu/aedmans/Rowe.pdf. Accessed 01 Sep 2023

23. “How does Nike’s Supply Chain Work?”. ADEC Marketplace, https://marketplace.adec-innovations.com/blogs/how-does-nikes-supply-chain-work/. Accessed 01 Sep 2023

24. “25 Years Ago I Coined the Phrase “Triple Bottom Line.” Here’s Why It’s Time to Rethink It.”. Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2018/06/25-years-ago-i-coined-the-phrase-triple-bottom-line-heres-why-im-giving-up-on-it. Accessed 01 Sep 2023

25. “The Volkswagen emissions scandal explained”. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/business/ng-interactive/2015/sep/23/volkswagen-emissions-scandal-explained-diesel-cars. Accessed 01 Sep 2023

26. “BP greenwashing complaint sets precedent for action on misleading ad campaigns”. Clientearth.org, https://www.clientearth.org/latest/latest-updates/news/bp-greenwashing-complaint-sets-precedent-for-action-on-misleading-ad-campaigns/. Accessed 01 Sep 2023

27. “Greenwashing Files: ExxonMobil”. Clientearth.org, https://www.clientearth.org/projects/the-greenwashing-files/exxonmobil/#greenwashing. Accessed 01 Sep 2023

28. “Break Free From Plastic – Brand Audit Report 2022”. Breakfreefromplastic.org, https://brandaudit.breakfreefromplastic.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/BRANDED-brand-audit-report-2022.pdf. Accessed 01 Sep 2023

29. “The Triple Bottom Line: What Is It and How Does It Work?”. Indiana University, https://www.ibrc.indiana.edu/ibr/2011/spring/article2.html. Accessed 29 Aug 2023