Growth is a critical driver of corporate performance. An extra 5% revenue growth per year correlates with an additional 3-4% of shareholder returns—the equivalent of increasing market capitalization by 33-45% over a decade [1].

Yet very few companies manage to sustain long-term growth, and those that don’t eventually go extinct. Over the past eight decades, the average lifespan of a US S&P 500 company has dropped from 67 to 15 years [2].

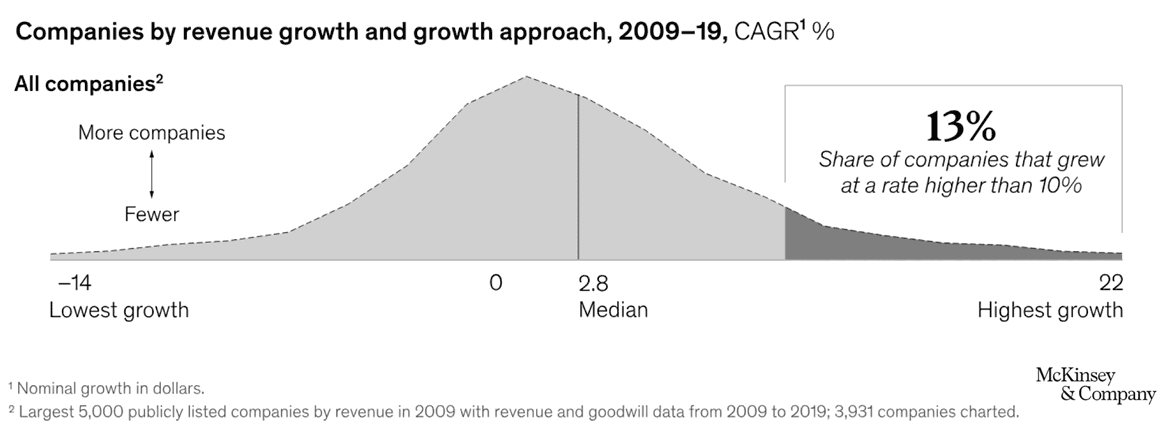

McKinsey research shows a typical company grew just 2.8% per year during the ten years preceding COVID-19, and only one in eight recorded more than 10% annual growth.

Young companies have the entrepreneurial drive and innovative culture required for growth. Operated by dynamic founders, there are limited areas to focus on as they strive to build wealth for themselves and their shareholders.

However, as companies mature, managing daily operations while pursuing long-term growth becomes increasingly challenging. Only a few can maintain a continuous pipeline of business-building initiatives that can power sustained growth over the long term.

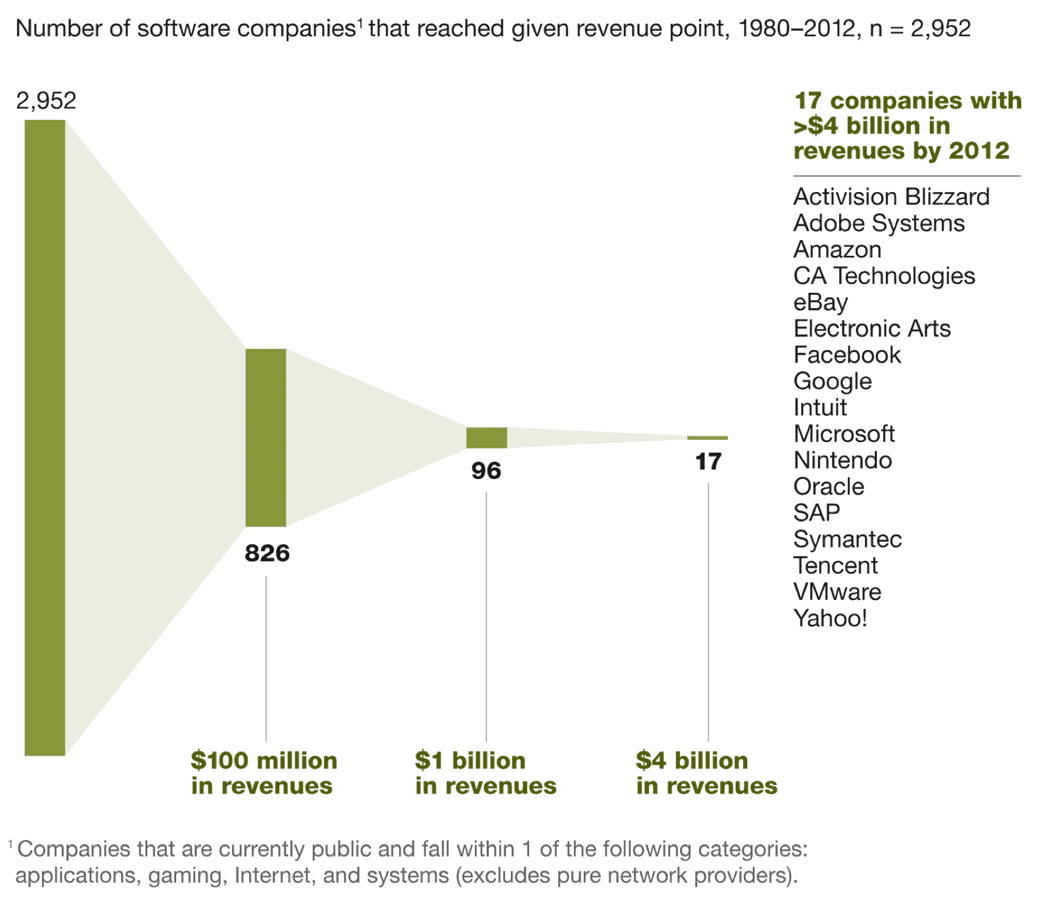

Take the software industry, for example, which witnesses an extraordinary number of startups, yet only a few grow to become giants. A McKinsey study of nearly 3,000 companies found that only 28% reached $100 million in annual revenues, 3% achieved $1 billion in annual sales, and just 0.6%—17 companies in total—grew beyond $4 billion [3].

What distinguishes companies that grow in the long run is their ability to create a pipeline of new businesses while successfully managing their core businesses.

Companies seeking to sustain growth cannot afford to leave gaps between the decline of one business and the ascent of another. They must not delay creating new businesses until their core business collapses.

However, most lack a coherent way to discuss current businesses, new enterprises coming on stream, and future options.

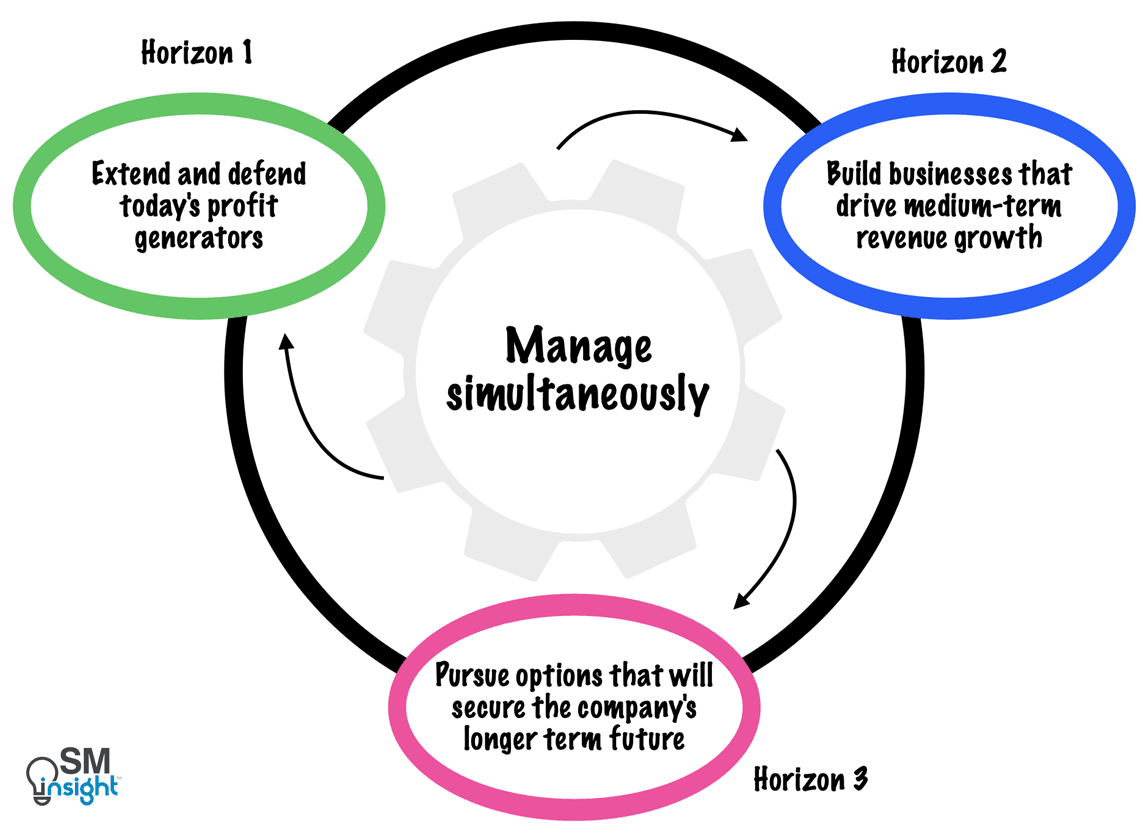

McKinsey’s Three Horizons of Growth Model provides a way of thinking to bridge this gap. It is one of the quickest ways to describe and prioritize innovative ideas in a large, mature company. The model helps balance the competing demands of running and building new businesses by offering a language that leaders at all levels can use.

The Three Horizons of Growth

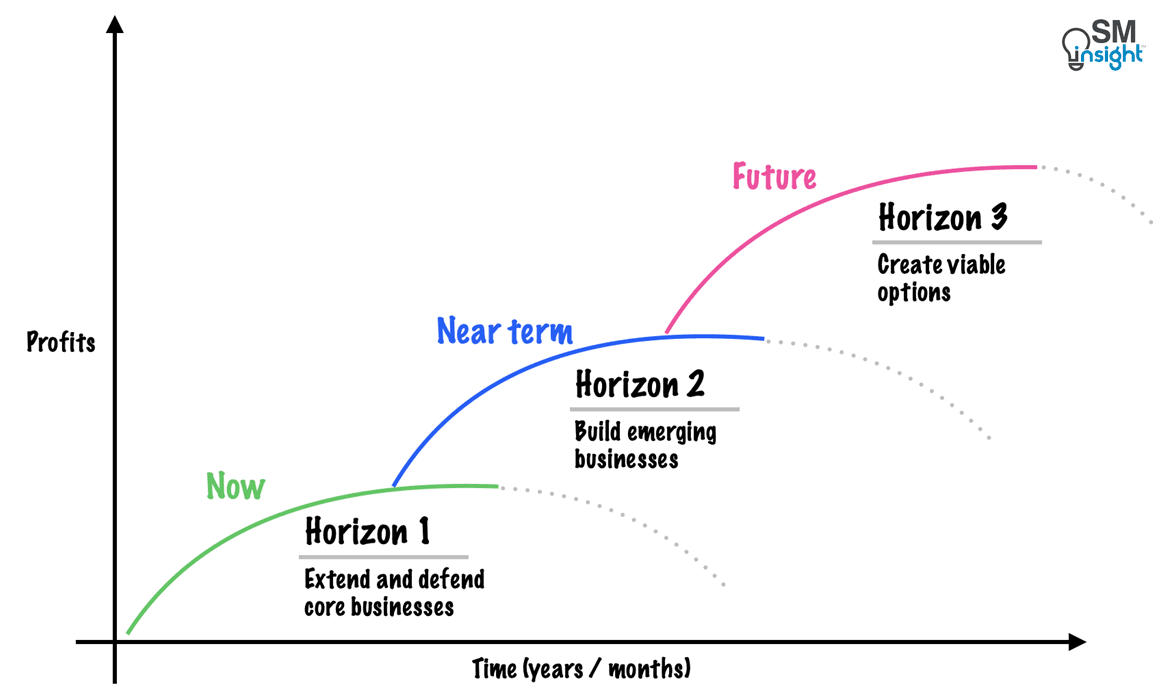

The Three Horizons of Growth Model helps actively manage a pipeline of continuous business creation by dividing them into three distinct stages, known as horizons.

Although a business pipeline could just as well be divided into four, ten, or twenty stages, doing so would only increase its complexity. A three-stage pipeline works best by helping to distinguish and manage the differing challenges and risks associated with mature, emergent, and early phases of a business’s life cycle.

The horizontal axis represents the timeline, while the vertical axis represents value (profit) potential. Given that timelines vary by product and industry, the model leaves the choice of timeline flexible, allowing companies to define it according to their industry and operational contexts.

Horizon-1

In horizon-1 are the businesses at the heart of an organization—those that customers and shareholders most readily identify the company with. Such businesses usually account for the lion’s share of current profits and cash flow and are critical to near-term performance.

The cash these horizon-1 businesses generate and the skills they nurture provide resources for growth. Without a successful Horizon 1, a company’s Horizon 2 and 3 initiatives will stagnate and die.

A few examples of horizon-1 businesses include search engine business for Alphabet (Google), office and cloud business for Microsoft, iPhone for Apple, and online retail business for Amazon.

Google generates nearly 60% of its revenue through search. People identify Google with search, and it is through search revenue that Google has managed to experiment with new technologies and invest billions into R&D and product development.

However, what has worked for over two decades may not work forever. Google’s search market share is almost 90%, limiting further expansion opportunities [5]. Meanwhile, AI-driven search engines such as Perplexity and Bing could begin to challenge Google’s dominance [6].

This is typical of horizon-1 businesses—while they usually have some growth potential left, they will eventually flatten out or decline. The primary challenge is to shore up competitive positions and fully capture the potential.

Innovation can incrementally extend growth and profitability in Horizon 1 through restructuring, productivity enhancement, and cost reduction; however, eventually, these businesses will lose steam and cannot power the company’s growth.

Horizon-2

Horizon 2 represents emerging businesses that could potentially transform the organization in the near future. These businesses attract investors’ attention and require considerable investment. Although significant profits may still be years away, these businesses generate some revenue, have customers, and may even be turning a modest profit.

Without Horizon 2 businesses, a company’s growth will slow and eventually stall.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a Horizon 2 business for most tech giants, including Alphabet, Meta, Amazon, and Microsoft. There is significant investor interest, and billions of dollars are being poured into research [7].

While AI may not be the core business for tech giants yet, it is embedded in some way into their products and can fundamentally disrupt (or augment) operations in the near future.

Horizon 2 initiatives usually require a single-minded drive to increase revenue and market share. When done right, they can complement or replace a company’s core businesses (Horizon-1) by extending or moving it in new directions.

Because building new revenue streams takes time and requires new skills, companies must have several emerging businesses (Horizon-2) on the boil and work on converting promising ideas into future growth drivers.

Horizon-3

Horizon 3 initiatives include research projects, market tests, pilots, alliances, minority stakes, and memoranda of understanding that have the potential to yield Horizon-1 levels of future profitability if proven successful.

They are more than just ideas on the whiteboard. They require management support and deliberate initiatives to develop into horizon-3 opportunities. This means seeding numerous options while knowing some will fail for internal reasons while others will fall victim to shifting industry trends.

Quantum computing, AI-powered drug discovery, and 3D-chiplet-based processors are some Horizon-3 examples in tech.

Such Horizon 3 initiatives are rarely proven, and most may never grow to become successful new businesses. Given the odds, a great deal of Horizon 3 activity is needed to cover a multitude of possible futures.

A company’s goal should be to keep the option to play open without committing too much capital or resources. The challenge is to nurture promising options while ruthlessly cutting those with diminishing potential. Without active Horizon 3 initiatives, a company’s long-term growth prospects will fade.

Managing the Three Horizons Concurrently

Because initiatives across the three horizons yield returns at different timelines, executives tend to put Horizon 2 and Horizon 3 initiatives on the back burner. This is a dangerous mistake and goes against how the three horizons should be managed.

Companies must focus on developing several businesses in parallel without regard to their stage of maturity. This differs from the traditional planning approach, where activities are deliberately deferred to the medium and longer term.

Each horizon requires a different focus, tactics, tools, and goals. To remain competitive in the long run, McKinsey suggests that a company must simultaneously allocate its management attention, R&D dollars, and resources across all three horizons.

This is akin to being a good farmer who must harvest the current crop, till the ground for the next season, and investigate new crops for the future—all concurrently. Neglecting any one horizon weakens a firm’s prospects of long-term growth.

What distinguishes companies that grow over the long term is their ability to innovate in their core businesses and build new ones simultaneously such that fading sources of growth are replenished at precisely the right moment.

The Horizon 2 Problem

When a mature company fails to develop a successful growth pipeline, it’s often due to what is known as the “Horizon 2 Vacuum,” [8] a term coined by Geoffrey Moore, author of the book Crossing the Chasm [9].

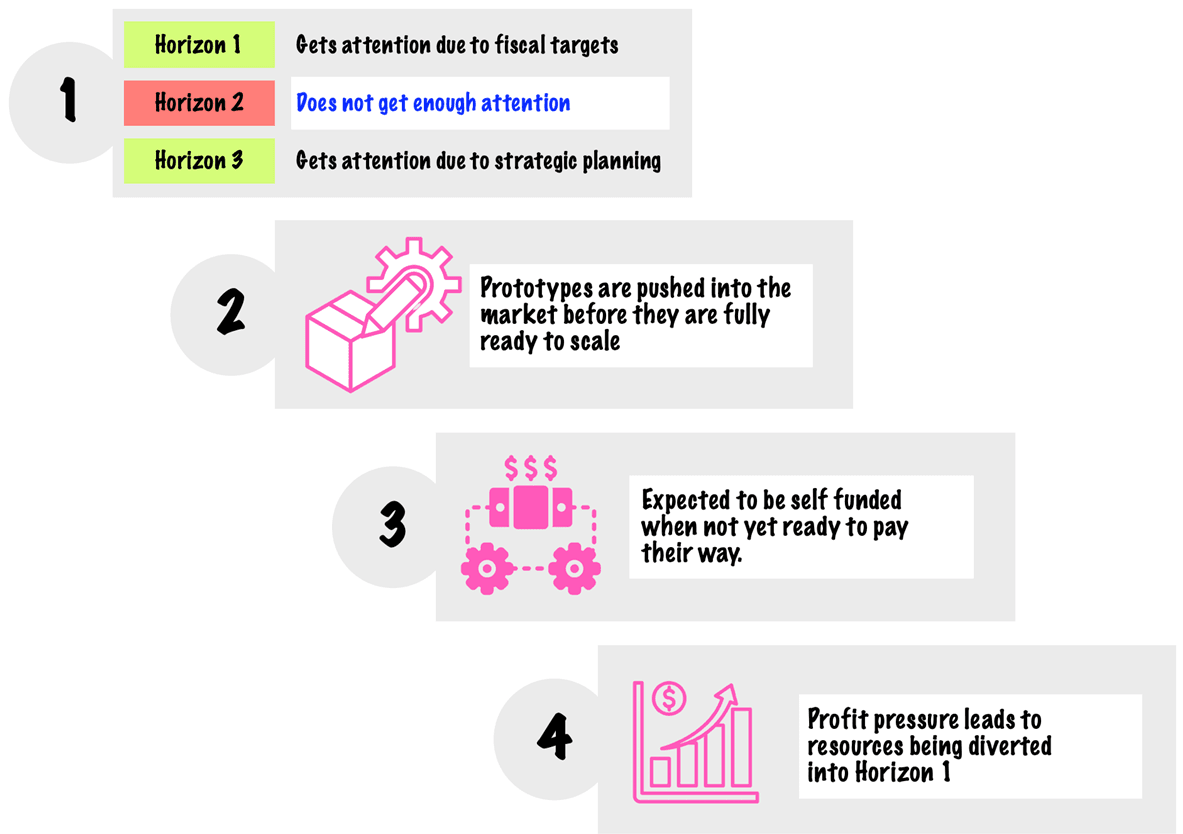

Because a company’s budgeting, reporting, and management focus on the current fiscal year, resources, time, talent, and attention are naturally allocated to Horizon 1 projects. Likewise, investor expectations mandate managers look beyond day-to-day concerns to formulate strategic plans, ensuring Horizon 3 also gets enough attention.

All this leaves little time and attention for Horizon 2.

Another problem stems from companies pushing prototype Horizon 2 products into the market when they are not yet ready to scale. Such products become demo baits attracting customers to whom Horizon 1 products are sold. This creates an illusion of growth that is not driven by Horizon 2.

A third problem arises when newly developed Horizon 2 products are expected to be self-funded when they are not yet ready to pay their way. The pressure for profits diverts resources toward Horizon 1 (because they’re more proven) while the company bleeds its Horizon 2 innovations dry.

For all these reasons, Horizon 2 falls into what is known as the “no man’s land” of the product pipeline. There are enough examples of good Horizon 2 failed products, including Microsoft Zune [10], Samsung Bixby [11], Amazon Fire Phone [12], Google Glass [13], and Intel’s forays into anything beyond the processors [14].

Moore has suggested strategies to overcome this challenge [8]:

- Separate and insulate Horizon 2 from 1: Form dedicated teams/functions mandated with Horizon 2 specific KPIs and complete oversight of the projects.

- Use acquisitions to fill the vacuum: Horizon 2 innovations may need more time to scale fully. Acquiring related businesses can accelerate time to market.

For example, Microsoft’s acquisition of GitHub in 2018 provided access to legions of developers who use GitHub’s code repository every day. The strategic value GitHub brought was valuable for the developer environment, where Microsoft makes real money [15]. - Develop talent, not just products: Companies must move not only their products but also their talent from Horizon 3 to Horizon 2. Horizon 3-oriented R&D wizards can only take the products so far. To scale, companies need Horizon 2-oriented entrepreneurs.

- Focus on sound leadership, not just funding: often, companies assign their good leaders to high-revenue opportunities (Horizon 1), leaving the other two horizons to fend for themselves. This results in a series of false starts, ultimately leading the executive team to abandon their efforts.

- Blocking resource migration across horizon boundaries: Companies must decide which resources and how much they want to invest in each of the three horizons. Once determined, management must commit to addressing the resource hoarding and poaching problems that disrupt developing Horizon 2/3 businesses.

Using the Three Horizons of Growth Model

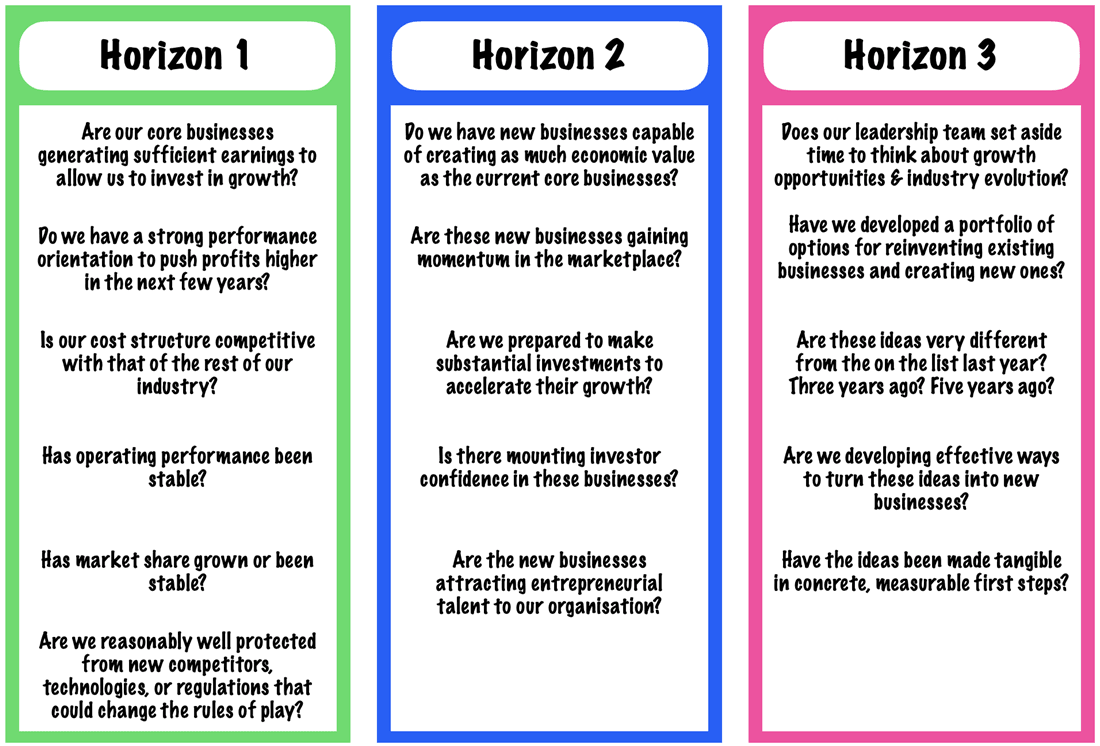

The three-horizon model forces leaders to question, “How healthy are our horizons looking?” Knowing strengths and weaknesses in the pipeline gives a good indication of how to prioritize growth initiatives.

Companies can begin by asking questions shown in each of the horizons in the illustration:

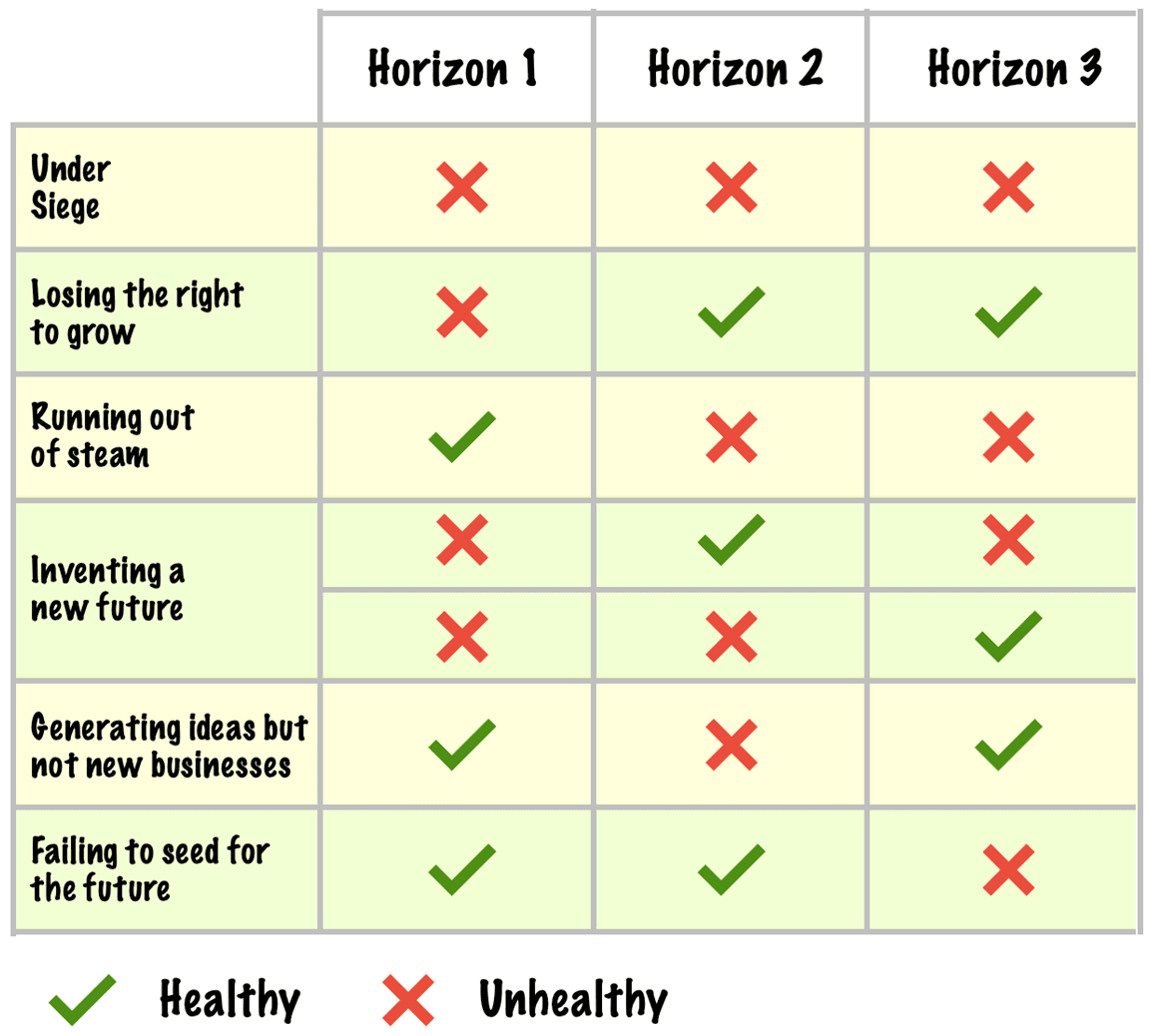

Six Unhealthy Patterns of Growth Pipeline

Companies that have managed to create three healthy horizons of growth do exist, but they are rare. If “yes” is not the answer to most of the above questions, then the company probably does not have a healthy pipeline and falls under one of the six unhealthy patterns:

1. Under Siege

This is the worst place to be where none of the horizons are healthy. While the core Horizon 1 business underperforms (or is unable to compete or facing imminent decline), there is no Horizon 2 pipeline to pick up the fast-losing momentum.

Rapid industry change or deregulation can force such a situation. Companies here face a double blow: not only will financial markets punish them as earnings decline, but investors will also look unfavorably at the capital investments needed to develop new businesses.

It’s hard to believe that Apple was in this situation in 1997. With increased competition from IBM and Microsoft, Apple introduced a series of new products that failed to sell [16].

When Steve Jobs returned, he focused on overhauling Apple’s product lineup, introducing new products like the iMac while also embracing the Internet, which rapidly became a source of growth for the tech industry. Efforts gradually paid off, and Apple’s situation improved.

2. LosingtThe Right to Grow

Companies in this category focus excessively on growth, so much so that they forget to pay attention to Horizon 1 businesses. Since Horizon 2 and 3 initiatives cannot drive immediate growth, threats to the profitability of Horizon 1 business prompt drastic cuts in investment, endangering the very new businesses that the company is so passionate about.

In the 1990s, LEGO attempted to reinvent itself by designing complex new lines with specialty pieces. The idea, while good in theory, failed to resonate with kids. By the early 2000s, LEGO suffered hundreds of millions of dollars in losses and was forced to get back to its proven products [17].

3. Running Out of Steam

These companies focus excessively on core businesses and cannot think beyond them. A fixation on boosting efficiency and cutting costs drives performance in the short term, but eventually, such companies face diminishing returns.

Throughout the ‘90s and early 2000s, Blockbuster was the go-to video rental company in the US. The company was so focused on its “old way” of doing business—the physical rental of VHS cassettes (and later, DVDs)—that it failed to spot the opportunity in digital streaming.

Mostly driving profits by charging “late fees” to customers, Blockbuster failed to spot value in the subscription-based model that Netflix introduced. The company even turned down an opportunity to purchase Netflix for $50 million. Blockbuster went bankrupt in 2010 [18].

4. Inventing a New Future

This is a situation where a company has promising Horizon 2 or 3 businesses but no viable Horizon 1. This is common in startups whose businesses have yet to post substantial profits.

OpenAI, for example, is leading the forefront of AI innovation and is valued by investors at over $150 billion. However, profitability is still years away. According to one report, between 2023 and 2028, OpenAI is expected to lose $44 billion [19].

While rare, this kind of situation can also occur in large companies due to abrupt shifts in competitive structure that change the external environment.

5. Generating Ideas But Not New Businesses

These companies have strong Horizon 1 businesses and lots of Horizon 3 ideas, but they fail in the middle. Little effort and focus is put into turning ideas into real businesses, resulting in an empty Horizon 2.

This is dangerous because Horizon 3 options provide a false sense of security while inflating market expectations for growth far beyond what the company is capable of. Investors begin penalizing the company as the gap between expectations and growth widens.

In 2010, IBM was in this situation with Watson AI, which was once hailed as a revolutionary force in artificial intelligence. IBM entered the healthcare industry with grand ambitions of assisting doctors by processing vast amounts of medical data, helping to diagnose complex diseases, and recommending treatment plans.

However, Watson wasn’t flexible enough and struggled to find a market as physicians grew frustrated, wrestling with the technology rather than caring for patients. Watson failed to lift IBM’s fortunes as the company trailed rivals that emerged as AI leaders. [20]

6. Failing to Seed For the Future

These companies have strong earnings in Horizon 1 and promising businesses in Horizon 2, enough to drive profitable growth for several years; however, they fail to institutionalize innovation and thus lack Horizon 3 options.

Such companies must also manage high market expectations due to healthy Horizons 1 and 2. This puts pressure on building new businesses, but an ability to identify and manage an expanding number of growth opportunities is lacking.

Intel, for example, has been a long-time leader in semiconductor technology since its inception in the 1960s. The company, however, missed the AI transition as competitors such as Nvidia, AMD, and TSMC capitalized on chips that could accelerate AI filled the market [21].

Factors to Consider When Deciding the Timeline

The key to sustained growth is to have the next growth engine ready before the current one slows. This is hard to predict and can vary from one company to another. As a minimum, the following factors must be considered when assigning timelines to horizons:

- The pace of industry evolution: Fast-evolving industries such as tech have shorter timelines, with their Horizon 3 not stretching beyond a year or two. Investors in such industries respond to future growth rather than current profits, forcing executives to innovate faster.

- Degree of uncertainty: unexpected changes to the external environment, such as deregulation, consolidation, or technology, increase complexity and can threaten core businesses, making it all the more important to have a portfolio of business-creation opportunities.

- Management and financial capacity: the greater a company’s financial and available management talent, the more Horizon 2 and 3 initiatives it can support. Companies must avoid stretching themselves too far with Horizon 2 and 3 initiatives at the cost of Horizon 1 businesses.

- Shareholder expectations: when investors are willing to accept volatility, the balance tilts towards Horizons 2 and 3. This raises market expectations and rewards the company with higher market capitalization.

Criticism of the Model

Some critics argue that the three-horizons-of-growth model made sense in the 20th century, when ideas took years to research, engineer, and deliver. They argue that the horizons are no longer bounded by time in a world where disruptive Horizon 3 ideas can be delivered as fast as ideas for Horizon 1 in the existing product line [22].

For example, Uber, Airbnb, Lyft, SpaceX, and Tesla are all Horizon 3 disruptions that used existing technologies and were deployed in extremely short periods. Such new products and services look like minimum viable products—barely finished, iterative, and incremental prototypes—but they can disrupt incumbents by scaling rapidly.

Sources

1. “The ten rules of growth.” McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-ten-rules-of-growth. Accessed 05 May 2025.

2. “How businesses can stand the test of time.” EY, https://www.ey.com/en_gl/insights/consulting/how-businesses-can-stand-the-test-of-time. Accessed 05 May 2025.

3. “Grow fast or die slow.” McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/technology-media-and-telecommunications/our-insights/grow-fast-or-die-slow. Accessed 05 May 2025.

4. “The Alchemy of Growth: Practical Insights for Building the Enduring Enterprise”. Mehrdad Baghai, Steve Coley, David White (Author) and Stephen Coley, https://www.amazon.com/dp/0738203092. Accessed 05 May 2025.

5. “Search Engine Market Share Worldwide”. Statcounter, https://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share. Accessed 05 May 2025.

6. “Is Google Losing Search Market Share?”. Rand Fishkin, https://sparktoro.com/blog/is-google-losing-search-market-share/. Accessed 05 May 2025.

7. “Tech Giants Are Set to Spend $200 Billion This Year Chasing AI”. Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-11-01/tech-giants-are-set-to-spend-200-billion-this-year-chasing-ai. Accessed 06 May 2025.

8. “To Succeed in the Long Term, Focus on the Middle Term”. Geoffrey Moore (HBR), https://hbr.org/2007/07/to-succeed-in-the-long-term-focus-on-the-middle-term. Accessed 07 May 2025.

9. “Crossing the Chasm”. Geoffrey A. Moore, https://www.amazon.com/Crossing-Chasm-3rd-Disruptive-Mainstream/dp/0062292986. Accessed 07 May 2025.

10. “Former Microsoft Zune Boss Explains Why It Flopped.” Business Insider, https://www.businessinsider.com/robbie-bach-explains-why-the-zune-flopped-2012-5. Accessed 07 May 2025.

11. “Operation Shush: The rise and fall of Samsung’s unloved Bixby assistant.” Digital Trends, https://www.digitaltrends.com/mobile/the-rise-and-fall-of-samsungs-bixby-virtual-assistant/. Accessed 07 May 2025.

12. “4 Reasons Amazon’s Fire Phone Was a Flop”. Time, https://time.com/3536969/amazon-fire-phone-bust/. Accessed 07 May 2025.

13. “Google Glass: A history of the discontinued smart glasses, what they did, why they failed.” Business Insider, https://www.businessinsider.com/google-glass. Accessed 07 May 2025.

14. “Intel’s years of missteps leave it fighting for survival in the Nvidia-dominated AI era.” Fortune, https://fortune.com/2024/09/24/intel-gelsinger-semiconductor-chips-ai-amazon/. Accessed 07 May 2025.

15. “Why Microsoft Is Willing to Pay So Much for GitHub”. Paul V. Weinstein (HBR), https://hbr.org/2018/06/why-microsoft-is-willing-to-pay-so-much-for-github. Accessed 10 May 2025.

16. “Apple In The 1990s: Why It Nearly Went Bankrupt”. The Street, https://www.thestreet.com/apple/news/apple-in-the-1990s-why-it-nearly-went-bankrupt. Accessed 08 May 2025.

17. “Innovation Almost Bankrupted LEGO — Until It Rebuilt with a Better Blueprint.” Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/innovation-almost-bankrupted-lego-until-it-rebuilt-with-a-better-blueprint/. Accessed 09 May 2025.

18. “Blockbuster: The rise and fall of the movie rental store, and what happened to the brand”. Business Insider, https://www.businessinsider.com/rise-and-fall-of-blockbuster. Accessed 09 May 2025.

19. “OpenAI Projections Imply Losses Tripling to $14 Billion in 2026”. The Information, https://www.theinformation.com/articles/openai-projections-imply-losses-tripling-to-14-billion-in-2026. Accessed 09 May 2025.

20. “What Ever Happened to IBM’s Watson?”. NewYork Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/16/technology/what-happened-ibm-watson.html. Accessed 09 May 2025.

21. “Intel was once a Silicon Valley leader. How did it fall so far?”. Vox, https://www.vox.com/technology/364745/intel-nvidia-ai-silicon-valley-layoffs-stock-semiconductor. Accessed 09 May 2025.

22. “McKinsey’s Three Horizons Model Defined Innovation for Years. Here’s Why It No Longer Applies.”. Steve Blank (HBR), https://hbr.org/2019/02/mckinseys-three-horizons-model-defined-innovation-for-years-heres-why-it-no-longer-applies. Accessed 10 May 2025.