There are limits to the value companies can generate by focusing purely on the price of the products and services they buy. When buyers and suppliers are willing and able to cooperate, they often find ways to unlock new sources of value that benefit them both.

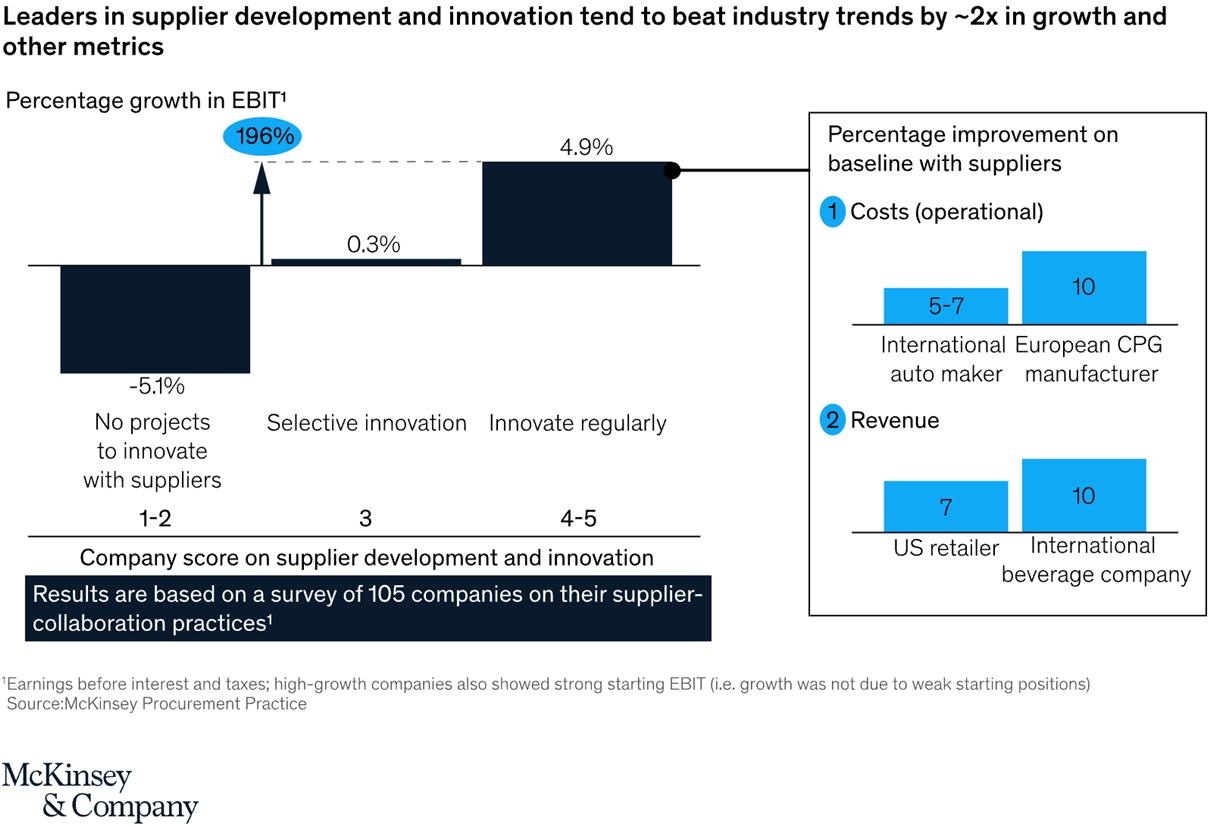

A McKinsey survey of more than 100 large organizations in multiple sectors revealed that companies that regularly collaborated with suppliers demonstrated higher growth, lower operating costs, and greater profitability than their industry peers[1].

Despite the value at stake, however, implementing supplier collaboration is hard and involves overcoming several challenges, such as:

- Investment of significant time and management effort before the generated value is evident.

- A collaborative approach that requires a mindset shift for both buyers and suppliers, moving away from transactional or adversarial interactions.

- Intensive, cross-functional involvement from both sides, a marked change to the normal working methods at most companies.

- Shifting from a cost-based to a value-based mindset necessitates a paradigm shift.

- Quantifying the actual value from collaboration is difficult, especially when companies pursue traditional procurement alongside suppliers or update product designs and processes.

- Companies might not have the skills and structures they need to design great supplier collaboration programs.

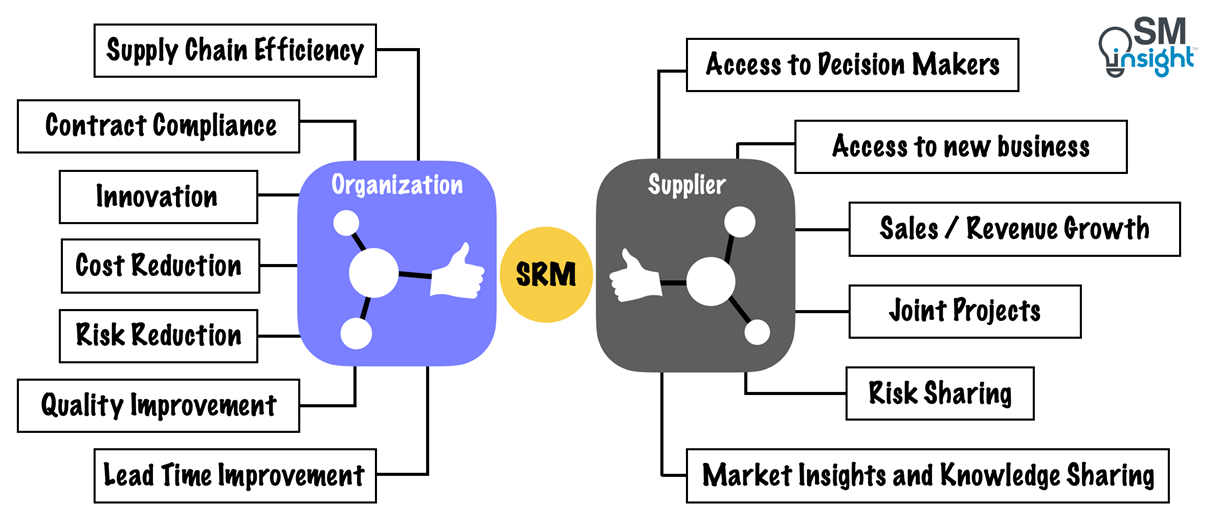

Thus, a systematic approach is needed to realize supplier collaboration and unlock value. Supplier relationship management (SRM) is an umbrella term that is about deciding the level of intervention and the extent and nature of any relationship needed with suppliers.

SRM focuses on joint growth and value creation with a limited number of key suppliers based on trust, open communication, empathy and a win-win orientation.

Why is SRM more critical than ever?

A changing world

Traditionally, supply chains were a linear collection of individual entities, each operating independently and with separate needs, interactions, and relationships. Companies only concerned themselves with their immediate supplier and customers with whom a contractual relationship existed.

This approach is no longer adequate to manage risk or gain a competitive advantage.

The pandemic has shown how the organizations that once flexed their corporate leverage found themselves working to make sure they could get the goods in the first place.

For example, the global semiconductor shortage triggered by the pandemic continues to disrupt automakers. Even in the fourth quarter of fiscal year 2023, established automakers like Ford Motor Co. have reported a 100,000-vehicle shortfall primarily due to chip supply issues.[2]

These disruptions in supply chains around the world have painfully brought flawed supplier relationships to light. They have made it abundantly clear that trust between companies and their suppliers is integral to building a resilient supply chain.

A shifting supply chain landscape

The political uncertainties, unprecedented environmental events, and exceptional peaks in demand for certain raw materials suggest companies can no longer take their suppliers for granted.

For example, China currently controls 70%-80% of the supply chain for EVs and lithium-ion batteries, increasing pressure on Western manufacturers to ensure their supply.[3]

Social responsibility is not an optional extra

Today, societal and environmental responsibility are not mere add-ons but essential expectation that influences investors’ and consumers’ purchasing choices.

Companies are under growing pressure to enhance sustainability practices, adopt clean energy sources, and eliminate unethical practices, such as child labor and slavery, throughout their supply chains.

Reputations and with it, billions of dollars are at stake.

For example, in March 2020, when a damning report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute revealed that the Chinese government was forcing hundreds of young Uyghur women to produce Nike shoes in the Taekwang factory, Nike’s reputation suffered a blow even though the company did not own the factory, nor directly have a contract with it.[4]

Instances such as these highlight the need for companies to have robust SRM practices.

Purchasing is a strategic function

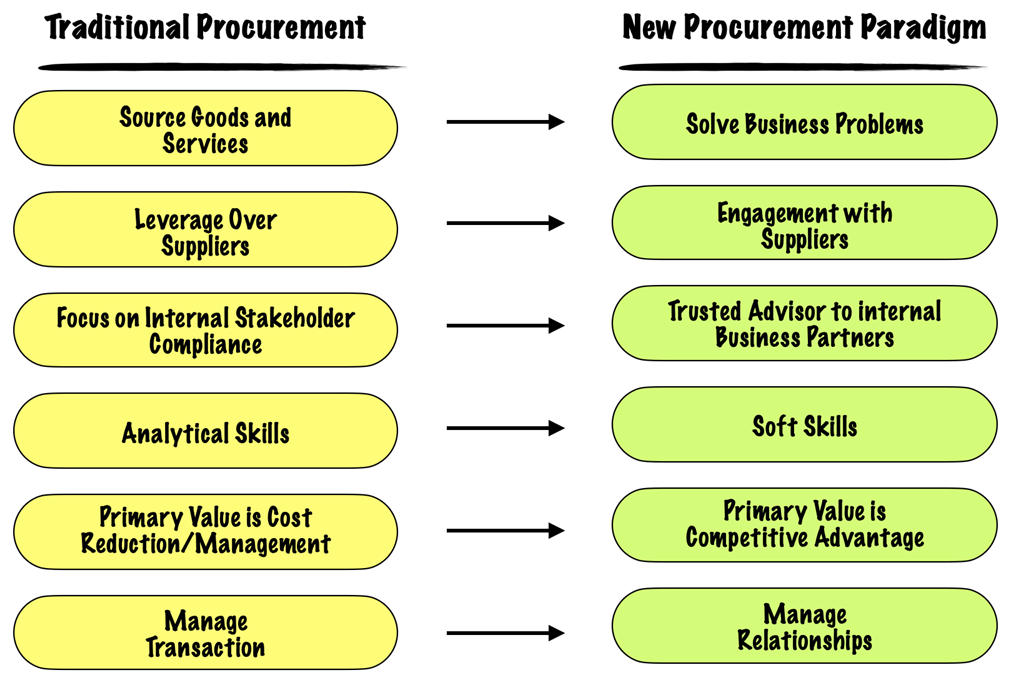

With the evolving role of purchasing in business, companies have realized the importance of its strategic contribution over the traditional cost-centered approach. Today, organizations recognize the need for a Chief Purchasing Officer, as suppliers are increasingly becoming integral to success. There is a shift in mindset from a tactical to a strategic one as companies look to increase engagement with suppliers for alignment with broader goals.

Better, faster, and more customized

Securing the lowest cost in the market for non-differentiated and commonly available goods and services is no longer a specialist activity. Globalization has widened the choices and alternatives. Somewhere in the world, there is a willing, cheap and sophisticated capability waiting to do even better, even faster and more cheaply.

The internet has created a new form of competitive tension, allowing access to all markets and real-time comparative pricing data. e-Auctions create a competitive environment for a specific requirement at the organizational level and consumers can now find the lowest price in seconds online.

The ability to create something personalized and unique for every customer is opening a new differentiation opportunity enabled through modularized production and new technologies.

Seven Principles of Effective SRM

The scope of SRM goes beyond implementing software solutions and “best practices” like holding supplier summits, designating supplier relationship managers, or implementing supplier scorecards.

While these approaches aren’t wrong, on their own, they rarely deliver significant benefits.

The greatest success is achieved when SRM focuses first and foremost on changing organizational culture and then transforming the way people within the company interact with their supplier counterparts on a daily basis.

Close attention must be paid to the people side of SRM and to individual mindset and skills. According to research, there are seven principles that are key to a successful SRM initiative:[5]

1. Focus efforts on suppliers with the greatest potential

Implementing SRM entails significant investment in change management. This investment should be carefully aligned with opportunities to create new value and/or better manage risk with suppliers.

Attempts to implement SRM in an undifferentiated fashion across too many suppliers typically result in wasted time and effort as well as reduced benefits. The central idea is to focus efforts on suppliers where there is the greatest potential to create value and reduce risk.

2. Treat all suppliers with a high degree of professionalism and respect

The tendency to treat some suppliers in a high-handed fashion is deeply ingrained in many organizations. A company that tolerates disrespect of even a few suppliers will find that such behavior inevitably leaks over into interactions with strategic suppliers as well, where it has a corrosive impact on the value realized.

3. Invest in understanding suppliers better

Getting to know suppliers and their strategies, business models, organizational structure, cultures, and capabilities enhances the ability to influence suppliers and identify opportunities to create more value.

4. Invest in helping suppliers understand the company better

Suppliers need to understand a company’s strategy, priorities, organizational structure

and culture, and policies and procedures. This increases the ability of key suppliers to align their resources and investments, develop solutions, and provide service in a way that optimally aligns with the company’s needs.

5. Actively build and sustain trust with suppliers

A lack of trust between customers and suppliers acts as a tax on productivity and a barrier to value creation. Conversely, a high level of trust between business partners facilitates more transparent and efficient information-sharing, as well as a greater willingness to invest time, effort, and capital.

Trust enhances the ability to identify new business opportunities, develop innovative solutions, understand and mitigate risk, and diagnose and expeditiously solve problems.

Companies can systematically cultivate trust by ensuring a cultural fit, using the right business model, and treating trust as a strategic choice:[6]

In a trading partner relationship, cultural fit can be summed up as having similar perspectives on how organizations work, communicate, and make decisions.

For example, if a company has an operating culture that values flexibility and innovation while its supplier’s culture is hierarchical and process-oriented, this incompatibility becomes a barrier to cooperation.

Similarly, sourcing business models plays a crucial role. When organizations procure goods and services, they have a choice of business model ranging from highly transactional (buying goods with a simple purchase order) to highly strategic contracts linked to ambitious business outcomes.

Unless contracts spell out the risks and rewards for delivering mutually desired outcomes, trust between parties can be negatively affected.

Developing trust is a strategic choice. It must be supported by conscious behavioral changes. Choosing to develop trust serves as a catalyst for improving relationships.

6. Being open to supplier feedback on the company’s performance

Companies often focus on scorecards that measure supplier performance and related value to the customer, but the root causes of many performance problems do not lie only with suppliers. Being open to supplier feedback and suggestions leads to value-creation opportunities that benefit both parties.

7. Invite and be open to supplier ideas and suggestions

As a part of sourcing and procurement strategy, organizations often develop tightly defined requirements and specifications, creating (or forcing) apples-to-apples comparisons between and among suppliers.

These tactics stem from a tendency to rely heavily on competitive pressure to get the best value from suppliers and motivate optimal performance.

While such approaches have undeniable benefits, companies can gain greater value by being less prescriptive and more willing to undertake apples-to-oranges comparisons between suppliers that have different business models and expertise.

By effectively communicating about the problem a company is seeking to solve, rather than imposing requirements on suppliers that constrain their creative ability, companies can unlock supplier innovation.

This requires sourcing and supply chain professionals to get closer to internal business partners and better understand the underlying needs and priorities of internal stakeholders as well as the unique capabilities of suppliers.

The table below summarizes the transformation required:

Creating sustainable value with SRM

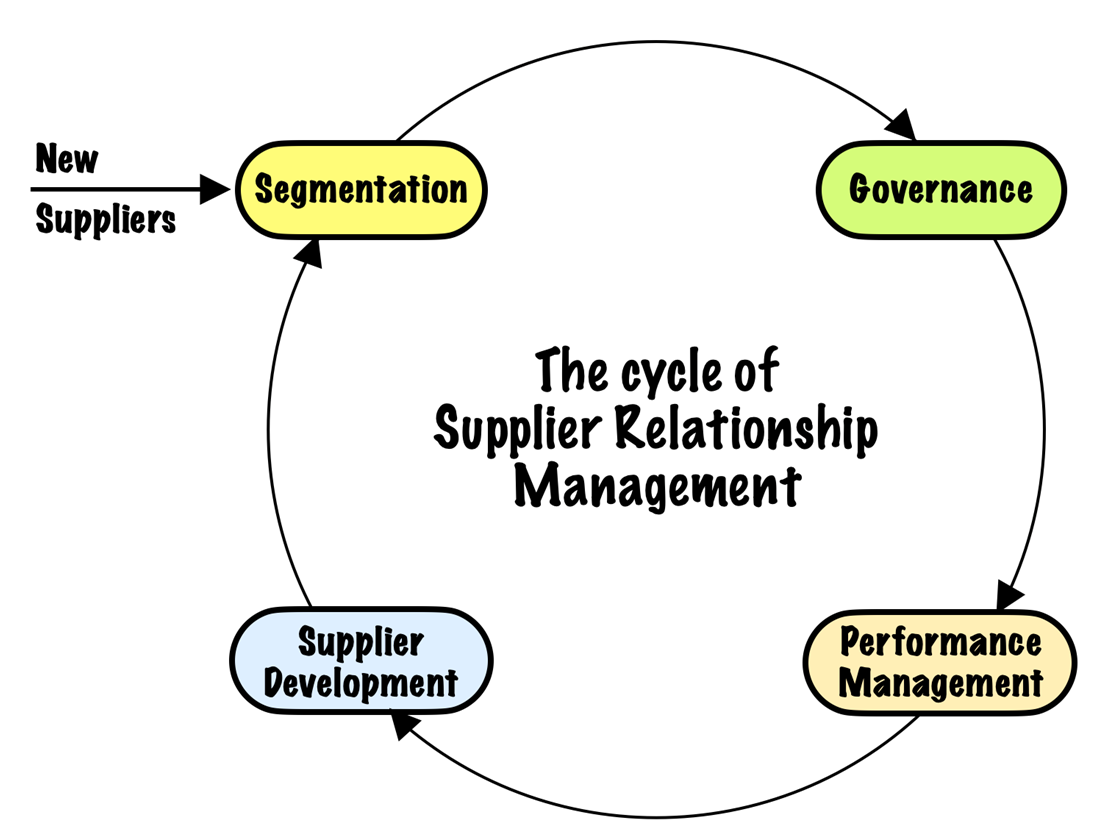

Companies can drive value out of their supplier relationships by organizing their SRM around a set of four core complementary processes:

1. Supplier segmentation:

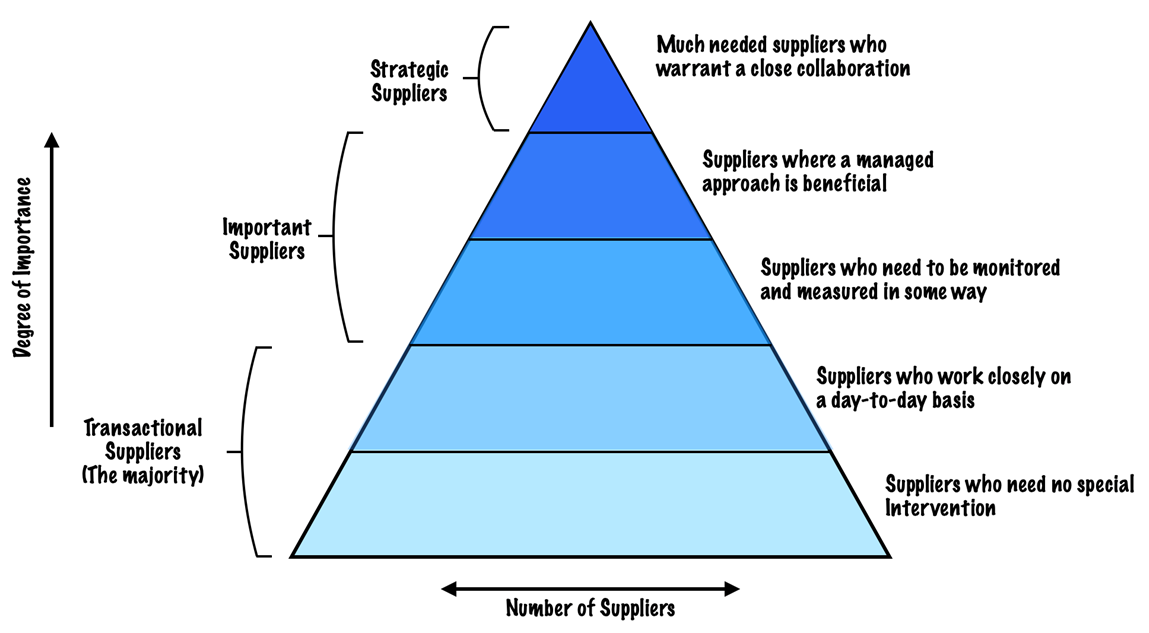

Organizations can concentrate their resources, time, and efforts on only a limited number of suppliers. Hence, it becomes extremely important that the selected group of suppliers are both relevant and strategic.

Supplier segmentation is the process of categorizing suppliers based on a defined set of criteria in order to identify the key (strategic) suppliers with which to engage in SRM.

Segmentation criteria are unique to the organization and should be developed according to what the organization is trying to achieve. It also involves a deeper market understanding.

While supplier relationships are typically prioritized based on spending and business criticality, it is unlikely that these two would cover all the needs of the organization.

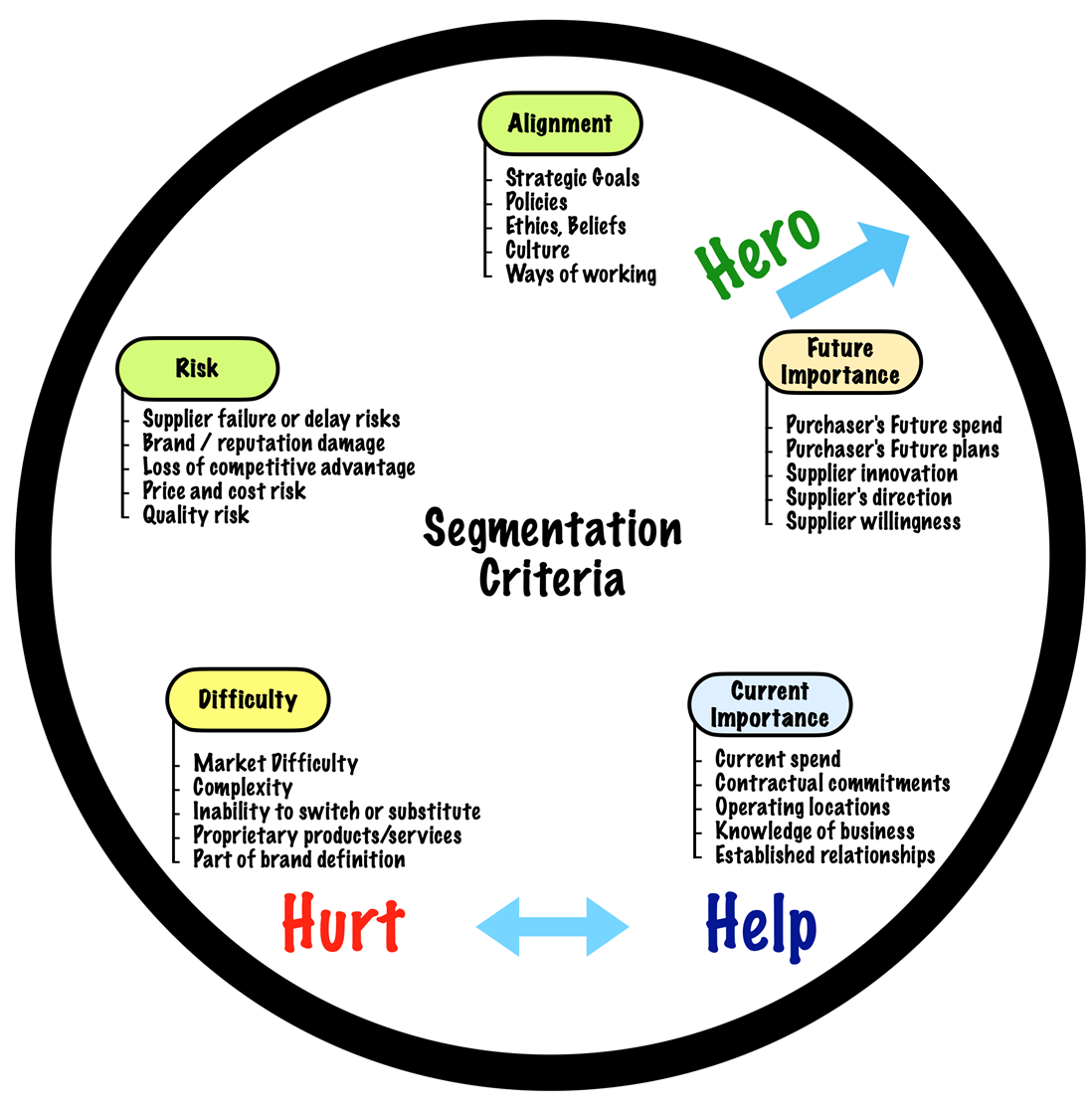

An effective segmentation demands a balanced judgment considering a range of factors and, therefore, demands a range of criteria. The below model provides a full generic segmentation based on five key criteria and is divided according to a supplier’s ability to hurt, help or be a hero.

Conducting segmentation requires a cross-functional workshop involving carefully selected participants and facilitated discussion and debate. It’s a resource-intensive activity which must be repeated periodically.

Applying the above model to an entire supply base with any degree of depth is unworkable. Thus, it becomes important to first apply Pareto principles[9] to filter out the vast majority of suppliers who are certainly not of interest.

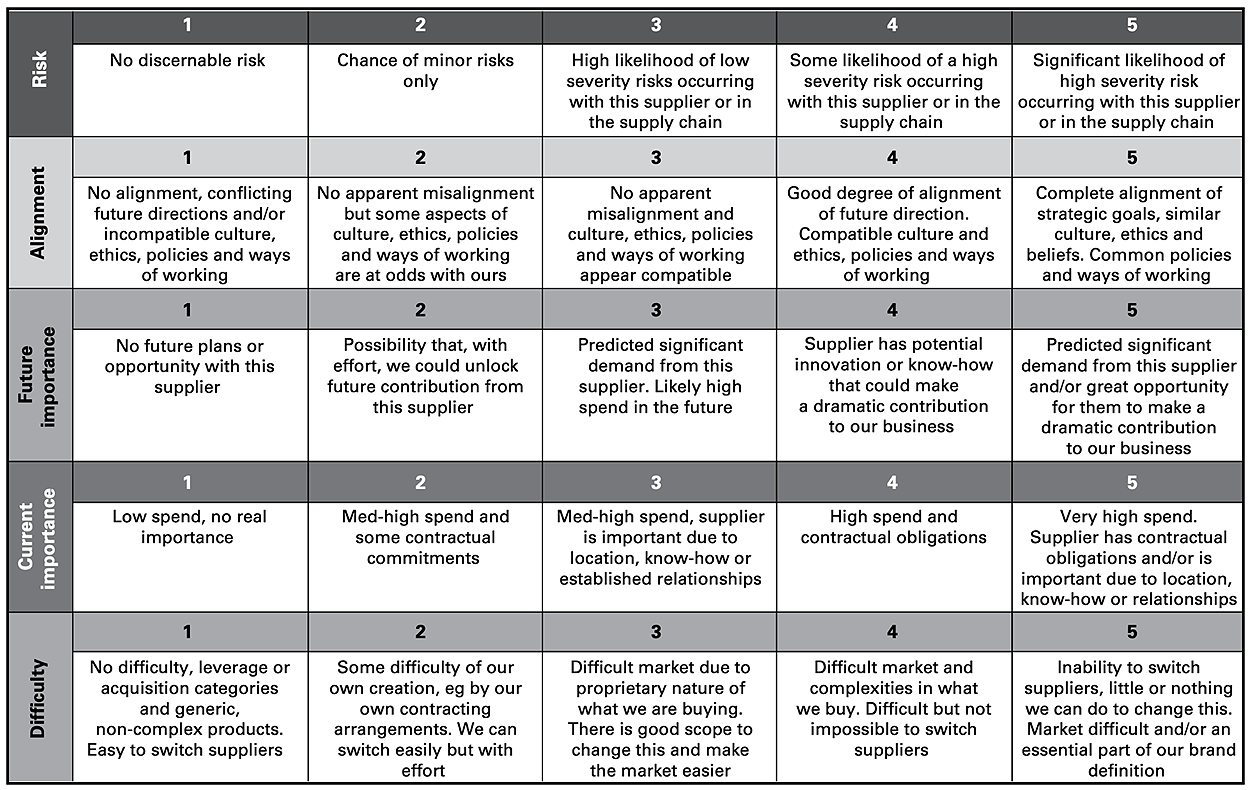

For each important supplier identified, the team can then assign scores against the segmentation criteria as shown:

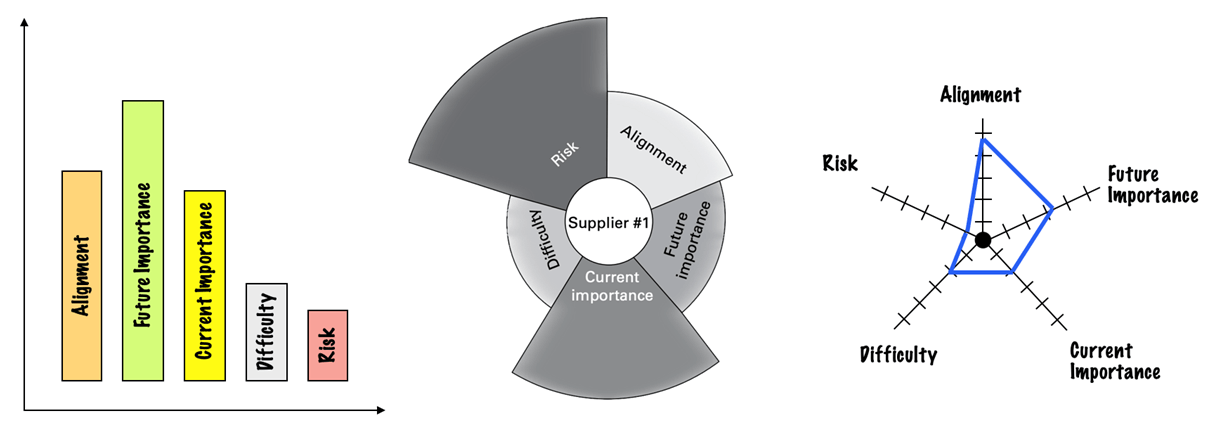

These scores are then converted into visual representations which allows conducting multi-dimension comparisons across many suppliers.

The segmentation process is a prerequisite to the next step, which is to set up effective governance with strategic suppliers.

2. Governance

Establishing effective governance is key to unlocking SRM value, especially for strategic suppliers. Hence, a robust internal governance process with clearly assigned ownership becomes important.

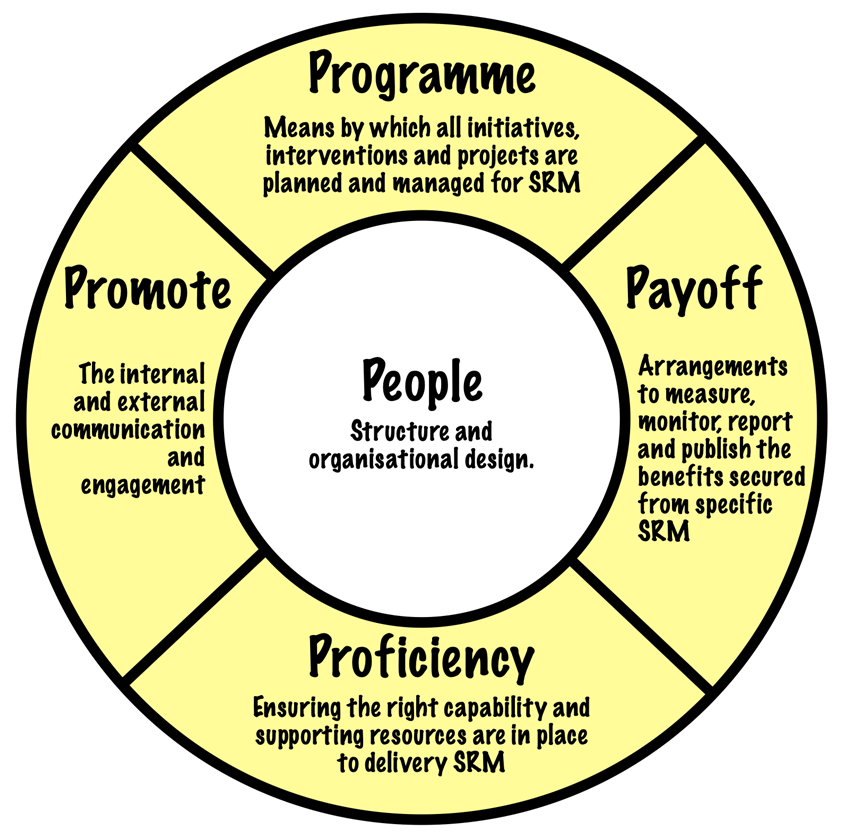

In SRM, governance encompasses what gets done, the processes that support it, decisions that are taken, how roles and responsibilities are agreed and arrangements to verify performance. There are five components within governance, called the 5Ps, as shown:

People

‘People’ concerns with the structure and organizational design. It is about the right people, with the right capability, doing the right things.

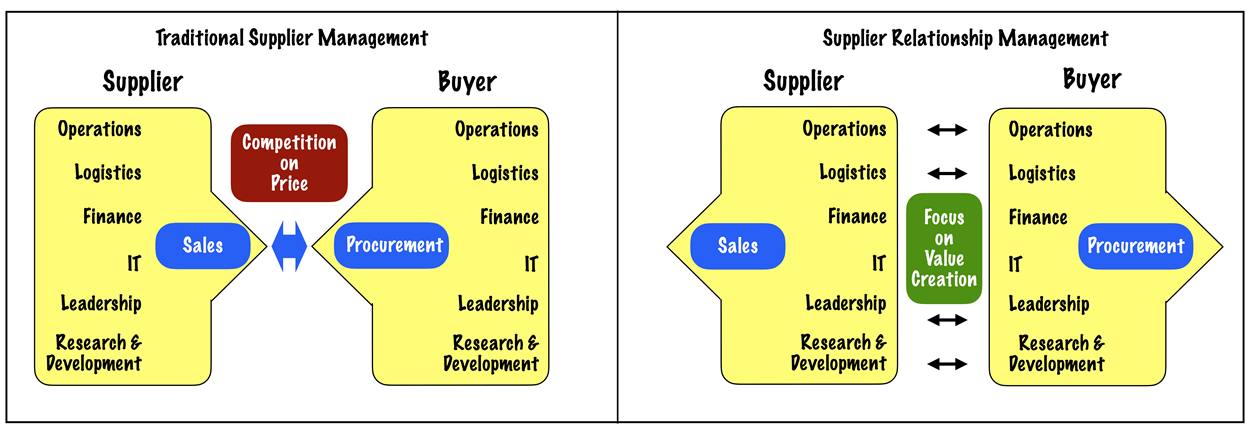

Unlike traditional supplier management, where procurement (buyer side) and sales (supplier side) are typically the single point of contact, SRM advocates interactions across functions with a focus on value creation as shown:

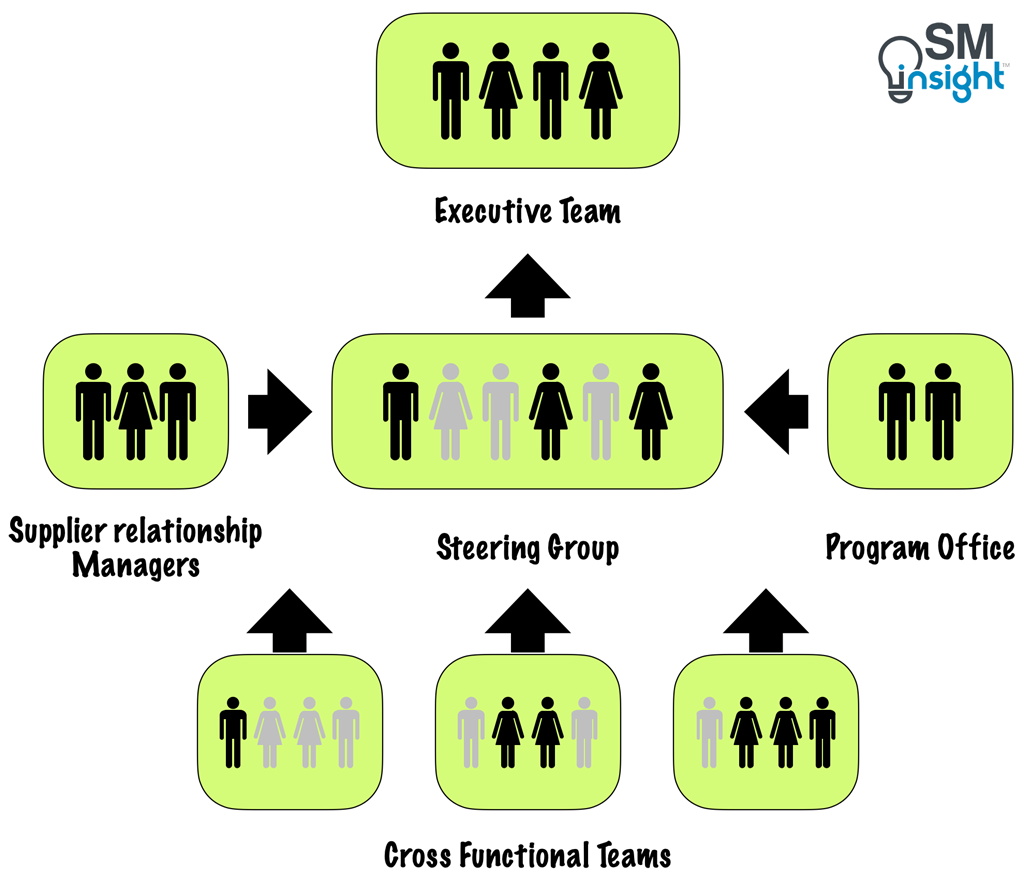

Hence, Joint improvement initiatives must be formalized with a clear governance structure as shown:

Key to this structure is the steering group – a small group of senior individuals responsible for coordinating all the components of governance and determining how strategic corporate objectives are met.

Proficiency

Ensuring that the right capability and supporting resources are in place is crucial to a successful SRM initiative. This involves selecting the right individuals to lead or participate and ensuring those selected are adequately trained and equipped for the job they are required to do.

The steering group must drive initiatives like competency assessment, learning and development, coaching and educating the team on wider business perspectives.

Promote

Internal and external communication and engagement are important for the success of SRM.

Good internal communication enables business engagement and alignment towards a single cause and reduces the likelihood of the supplier dividing and conquering. It also helps to ensure that any supplier intervention is aligned towards the entire needs and wants of the business and, ultimately, corporate strategy.

Governance also extends to external communications. For example, releasing high-level supplier briefing statements or publishing a supplier code of conduct helps ensure alignment.

Pay-off

Payoff consists of the arrangements to measure, monitor, report and publish the benefits of SRM interventions. Since SRM requires significant investment, the returns must be quantifiable and evident. Some of the key metrics (beyond price reductions) that can be used to track suppliers’ value include cost avoidance, efficiency improvements, value Improvements and Brand Development.

Programme

The Programme encompasses all initiatives, interventions and projects which are planned and managed for SRM. It is about identifying priorities and planning how these will be acted upon based on available resources.

It is managed using a dynamic programme plan identifying the key projects and activities over the short to medium term.

It is the steering group’s responsibility to develop and maintain a current programme, meeting regularly to review progress and update the programme as appropriate. These reviews should cover:

- Overall progress against expected headline benefits.

- Review of progress against benefits for individual initiatives.

- Review of progress to milestones for individual initiatives.

- Review of communication plan.

- Ensuring the availability of the required capabilities and resources.

- Review and update of the programme plan.

3. Performance management

Performance management is the process of targeted evaluation, measurement and monitoring of supplier performance and supplier’s business processes and practices in order to achieve desired business outcomes and goals.

Unfortunately, there is no one-size-fits-all metric.

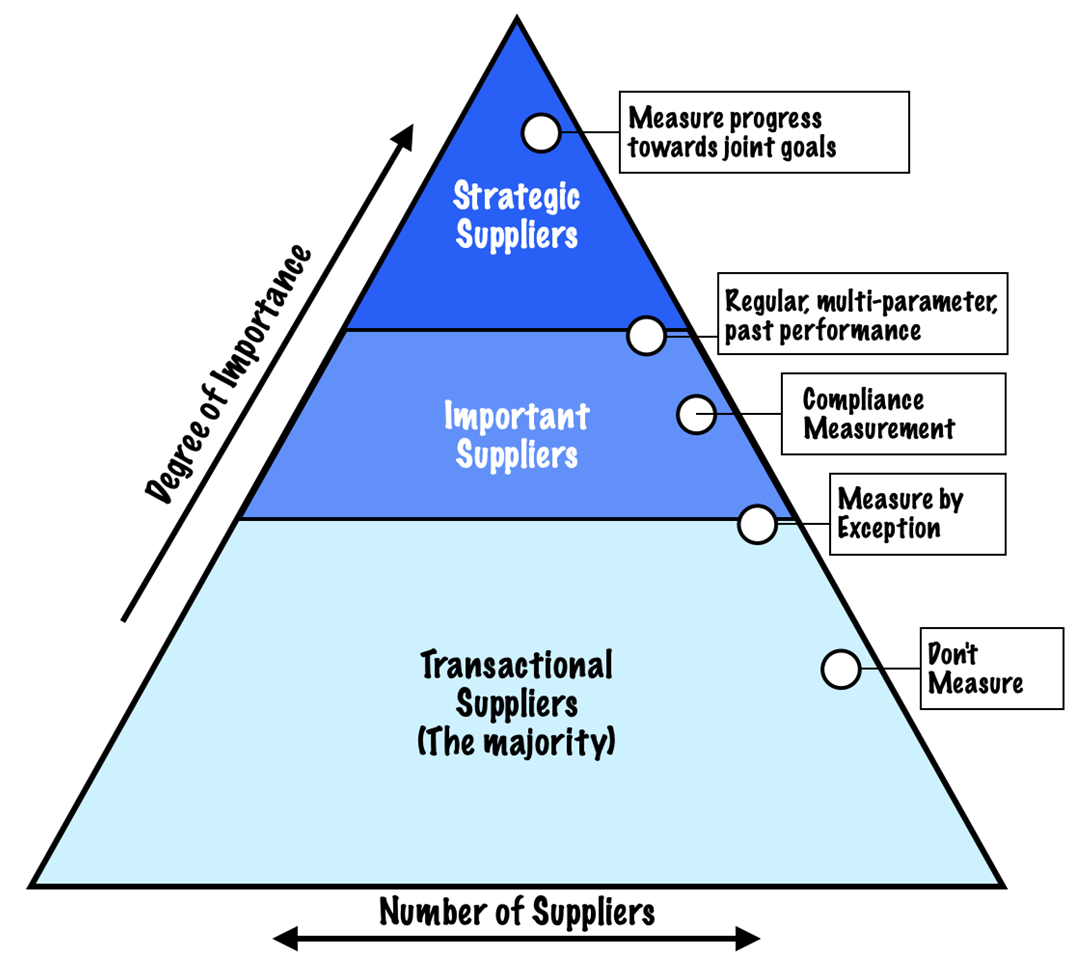

Businesses need to adopt different supplier performance measurement approaches and the relevance or usefulness of each depends upon how important the supplier is.

Broadly, there are four degrees of measurement an organization could adopt which correlates with the degree of importance of a supplier:

1. Measuring progress toward joint goals

Suited to measure the most strategic suppliers, this measurement system determines the degree of progress toward joint goals. It uses measures from past performance and interprets them to create leading indicators.

One way of using such a measure is to link supplier performance to customer performance such that if the company does well, the supplier knows about it. The supplier’s performance can then be measured based on their contribution to the success.

2. Regular, multi-parameter, past performance

Involves the selection and presentation of measures across multiple parameters that collectively represent a supplier’s performance to date. This type of measurement

approach is backward-looking and considers not just past performance but also identifies trends to help guide decision-making.

3. Compliance measurement

Involves regular measurement of one or more parameters to verify compliance against a defined level of supplier performance.

Compliance measurement typically takes place at the point of goods delivery or service provision, so there is a facility to reject anything that does not comply beforehand. It is more concerned with “checking” than measurement and is mandatory in some situations.

For example, in a safety-critical industry, certain raw materials need to be measured against key parameters.

Companies can implement Compliance measurement through sampling where a defined percentage of an overall batch can be checked, or it may be a single event or an ongoing regular and repeat activity. In the case of the latter, maintaining a record of past performance enables sample sizes to be varied according to overall performance trends

4. Measurement by exception

This involves measurements only when things go wrong. For example, when a supplier becomes problematic, a purchaser might want to start measuring performance in order to understand and fix the issue.

For effective performance management, once the degree of measurement is in place, the supplier scorecard must be continuously monitored. Review meetings should be regularly held with strategic suppliers. Any deviation from agreed minimum performance requirements should be addressed immediately by identifying the root cause and putting corrective measures in place.

4. Supplier development

Supplier development is deliberate action or intervention aimed at increasing the supplier’s capability and performance in line with future business needs.

It could be driven in response to a problem or need to improve when exposed to risk, or an opportunity for both parties to secure greater benefit by developing the supplier.

Companies can undertake the following actions in order to develop a supplier:

- Training – Invite the supplier or go to them and conduct specific training and share knowledge and experience.

- Implant people to work with the supplier – sending the right people with the right skills, experience, or abilities to work with a supplier can help develop a supplier through knowledge sharing. The supplier must be able to organize and realize the full potential of the opportunity. Hence, at the outset, it is important to decide how people will work with the supplier, what they will work on, what the supplier will do to maximize the benefit and so on.

- Have the supplier come to the purchaser – a similar development can be made possible if the supplier can have their people come and work with the purchasing organization. Ensuring that the right people are given the ability to work in the right areas is critical to success.

- Consultancy – provide focused bursts of help on a consultancy or technical assistance basis.

- Sharing resources – sharing of resources is a way to add value to a supplier and help ease constraints. For example, spare building space could be provided to support a specific project (through appropriate contractual provisions).

- Developing supplier role models – where a relationship with one supplier has been developed to be highly effective, the supplier can act as a role model to help other key suppliers develop.

Supplier development demands an investment. It could be made for free or through some sort of arrangement for the supplier to contribute either directly or indirectly. Either way, the supplier must agree to participate and invest time and effort.

The basis of segmentation serves as a guide to deciding the degree of investment to be made. Additionally, in the below scenarios, development efforts may be worthwhile:

- The supplier is unable to achieve the degree of development needed without help.

- The supplier does not know how to develop.

- The purchaser can see potential in the supplier that they themselves cannot.

- There are great mutual benefits to developing together.

- The benefits of building a strong relationship negate the effort to get there.

SRM at Toyota and Honda

The automotive industry has always been known for its contentious manufacturer-supplier relationships. However, automotive giants Toyota and Honda have bucked the trend, leading the way in establishing good supplier relationships that go beyond just price.[11]

Collaboration has been the key. The Japanese concept of keiretsu[12], a close-knit network of vendors that continuously learn, improve, and prosper along with their parent companies, is the underlying strategy behind Honda and Toyota’s supplier relationships.

As a result, Toyota and Honda have consistently ranked 1 and 2 in Plante Moran’s annual OEM-Supplier Working Relations Index every year since 2011.[13]

![Plante Moran’s annual OEM-Supplier Working Relations Index[13]](https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/wp-content/uploads/Plante-Moran-annual-OEM-Supplier-Working-Relations-Index.png)

The importance of company culture in driving successful supplier relationships is evident in American automotive companies’ failed attempts to implement keiretsu which was briefly in vogue within the 1980s.

Its prominence was short-lived as the American companies prioritized the immediate benefits of low-wage costs over the benefits of investing in relationships. As “cheaper, faster, better” took priority, supplier relationships suffered.

For Honda and Toyota, suppliers are key drivers of innovation and success. While the two companies outsource over 70 percent of their manufacturing costs, their suppliers return the favor.

For example, many of the cost-cutting ideas that made the Accord and Camry so successful came from suppliers.

Another win-win example is Target pricing. Toyota and Honda know what price the market can bear and their suppliers’ capabilities. Working backwards, they break down the cost one piece at a time to offer some of the most competitive cars on the market.

For worthy suppliers who cannot meet target prices, the automakers set up pricing schedules, giving them up to three years to improve.

Working with suppliers to develop technology, Toyota invites its supplier’s engineers to work alongside its own engineers for two or three years. This extensive training allows suppliers to fully integrate with the manufacturers’ processes and, eventually, develop design ideas of their own. The experience makes the suppliers more technologically advanced and increases their value to Toyota.

And the office swapping goes both ways. Honda, for example, often sends its engineers and occasionally its senior executives to suppliers’ facilities to study their operations and cultures.

SRM as a Competitive Differentiator

As companies become increasingly dependent on suppliers, not just for goods and services but also to support research and development activities, product design, development, and innovation, Supply management strategies and practices will need to catch up to the reality of new risks and new opportunities.

This will require business and supply chain leaders to view and treat suppliers as business partners and not just vendors. Creating opportunities and incentives for suppliers to make investments and align resources will become a business necessity.

Companies that can use SRM to become a “customer of choice” will stand to achieve a significant competitive advantage relative to their peers who fail to transform their approach to working with suppliers.

Sources

1. “Taking supplier collaboration to the next level”. McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/taking-supplier-collaboration-to-the-next-level. Accessed 24 Aug 2023

2. “Focus: Ford’s pain underscores uneven impact of two-year auto chip shortage”. Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/fords-pain-underscores-uneven-impact-two-year-auto-chip-shortage-2023-02-03/. Accessed 22 Aug 2023

3. “Lithium shortages: threat or opportunity?”. Mining Technology, https://www.mining-technology.com/features/lithium-price-challenges/. Accessed 24 Aug 2023

4. “The China Challenge: The Stain of Forced Labor on Nike Shoes”. Discourse, https://www.discoursemagazine.com/economics/2022/01/05/the-china-challenge-the-stain-of-forced-labor-on-nike-shoes/. Accessed 22 Aug 2023

5. “Getting the Most Out of SRM”. Jonathan Hughes and Jessica Wadd, https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/594420/2012.01_Getting%20the%20Most%20Out%20of%20SRM_SCMR.pdf?__hstc=&__hssc=. Accessed 22 Aug 2023

6. “3 Ways to Build Trust with Your Suppliers”. Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2022/11/3-ways-to-build-trust-with-your-suppliers. Accessed 22 Aug 2023

7. “Supplier Relationship Management (SRM) Redefining the value of strategic supplier collaboration”. Deloitte, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/de/Documents/operations/Supplier_Relationship_Management_2015.pdf. Accessed 23 Aug 2023

8. “Supplier Relationship Management: Unlocking the Hidden Value in Your Supply Base 2nd Edition”. Jonathan O’Brien, https://www.amazon.com/Supplier-Relationship-Management-Unlocking-Hidden/dp/0749480130. Accessed 26 Aug 2023

9. “WHAT IS A PARETO CHART?”. American Society for Quality, https://asq.org/quality-resources/pareto. Accessed 26 Aug 2023

10. “Supplier Relationship Management How key suppliers drive your company’s competitive advantage”. PwC, https://www.pwc.nl/nl/assets/documents/pwc-supplier-relationship-management.pdf. Accessed 26 Aug 2023

11. “Deep supplier relationships drive automakers’ success”. Arizona State University – W. P. Carey News, https://news.wpcarey.asu.edu/20050706-deep-supplier-relationships-drive-automakers-success. Accessed 26 Aug 2023

12. “What Is Keiretsu? Definition, How It Works in Business, and Types”. Investopedia, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/k/keiretsu.asp. Accessed 26 Aug 2023

13. “Auto supplier and OEM relationships: Insights from the 2022 WRI® Study”. Plante Moran, https://www.plantemoran.com/explore-our-thinking/insight/2022/06/auto-supplier-and-oem-relationships-insights-from-the-2022-wri-study. Accessed 26 Aug 2023