Services constitute over 60% of the world’s GDP [1], yet measuring service quality is harder than measuring the quality of goods. While goods can be evaluated through tangible cues such as style, hardness, color, label, feel, package, and fit, few cues exist for services.

Evidence for service quality is often limited to physical facilities, equipment, and service provider’s personnel. Without tangible evidence, firms find it difficult to understand how consumers perceive their services.

What is SERVQUAL?

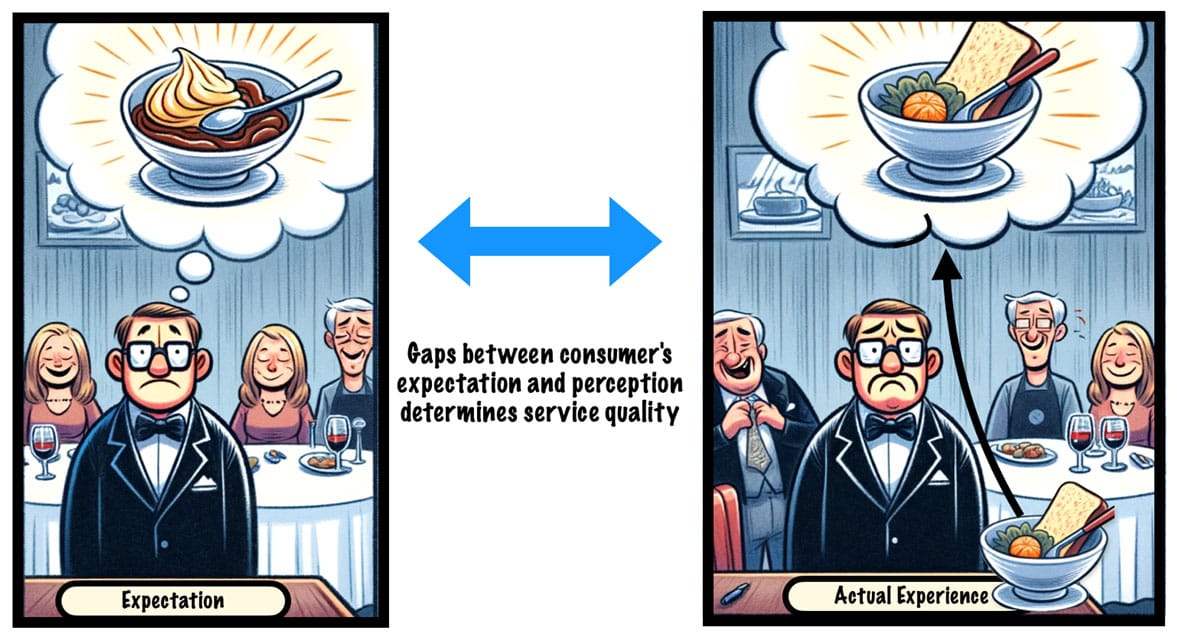

SERVQUAL is a multidimensional research instrument designed to objectively assess service quality. It is based on the expectancy–disconfirmation paradigm [2], which means that service quality is determined by comparing consumers’ pre-consumption expectations with their actual service experience.

Quality is perceived positively if the service meets or exceeds expectations; if it falls short, it is perceived negatively.

History of SERVQUAL

In the early 1980s, the importance of studying services separately from goods became apparent, but no one had seriously dedicated a research program to it [3].

In 1985, marketing experts A. Parasuraman, Valarie A. Zeithaml, and Leonard L. Berry launched a research program dedicated to understanding service quality and set out to answer two of the most difficult questions around it:

- “What’s the best way to define service quality?”

- “What’s the best way to measure it?”

The program resulted in the development of an instrument and accompanying service quality measure known as SERVQUAL—an acronym formed by merging two words, “service” and “quality,” together. [4].

First published in 1985, SERVQUAL was further developed, promulgated, and promoted through a series of publications.

While the first publication identified ten service quality dimensions (discussed later), in 1988, these components collapsed to five [5]. In 1991, the authors published a follow-up study that refined and reworded certain components of the SERVQUAL questionnaire [6].

SERVQUAL’s approach to defining and measuring service quality still pervades much of the quality literature. It remains a very popular, if not the most popular, measure of service quality for researchers and practitioners.

The instrument has been used to measure and improve service quality in various sectors, including healthcare, education, insurance, telecom, retail, and banking [7].

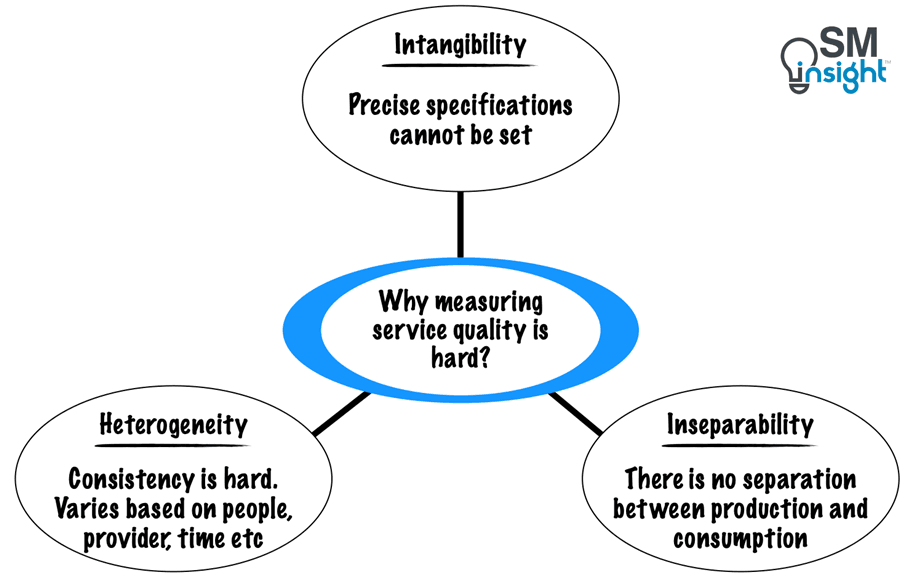

Barriers to measuring service quality

Services have three distinct characteristics that make measuring their quality harder than goods:

Intangibility

Because services are performances rather than objects, precise manufacturing specifications concerning uniform quality can rarely be set. Most services cannot be counted, measured, inventoried, tested, or verified before the sale.

Because of this intangibility, firms find it difficult to understand how consumers perceive their services and evaluate quality. In most cases, it cannot be fully assessed until the moment of consumption.

Heterogeneity

Services’ performance (especially those requiring manual interventions) varies from producer to producer, from customer to customer, and from day to day.

For example, your restaurant experience could be better when served by an experienced, attentive waiter than a new waiter still learning the ropes. It may even vary based on the time of the day and what menu you choose.

It is thus difficult to assure consistency of behavior from service personnel because what the firm intends to deliver may differ entirely from what the consumer receives.

Inseparability

In most services, there is no separation between production and consumption. Service quality is not engineered at the manufacturing plant and then delivered intact to the consumer. It occurs during service delivery, usually in an interaction between the client and the firm’s point of contact.

Consequently, the service firm has less managerial control over quality.

Another important factor is customer participation, which strongly influences how the service is delivered. For example, a doctor’s treatment quality may depend on how accurately the patient describes symptoms or adheres to the prescription.

Broad areas of service quality

Customers can have varying perceptions of what good service should be like, and the quality of service delivered is compared against those perceptions.

There are three broad categories of service quality that SERVQUAL focuses upon:

- Physical quality – the physical aspects of the service (e.g., equipment or building).

- Corporate quality – involves the company’s image or brand.

- Interactive quality – interaction between the company’s employees and customers.

While SERVQUAL aims to capture these aspects as a tool, it focuses less on the outcomes.

SERVQUAL gaps between delivery and expectations

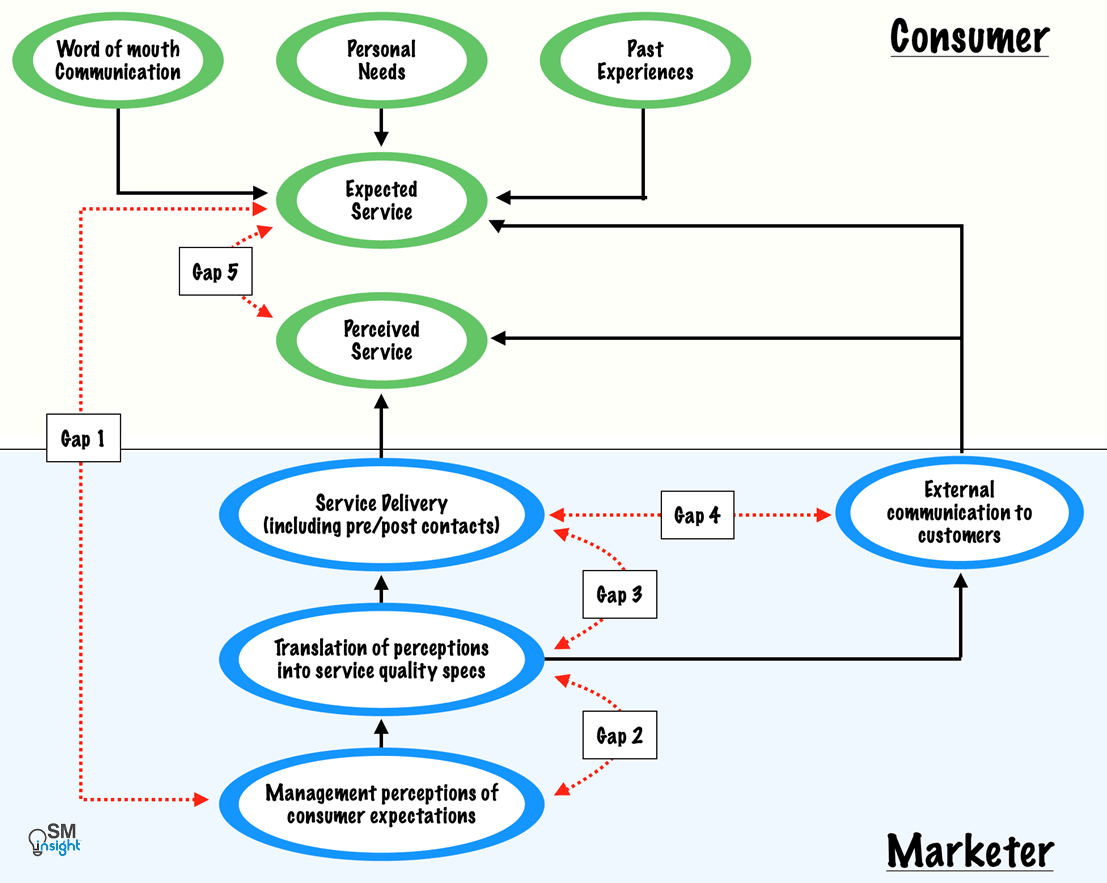

To develop SERVQUAL, authors Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry explored the key discrepancies between consumer expectations, executive perceptions in firms, how firms communicated to their customers (such as marketing and adverts), and service processes.

During this study, five main types of gaps emerged, which form the basis of how SERVQUAL is designed:

Gap 1: The Consumer Expectation—Management Perception Gap

Service firm executives may not always understand what features matter most to consumers, what features a service must have to meet their needs, and what levels of performance of those features are needed to deliver high-quality service.

For example, one hotel introduced a “pillow menu,” offering customers nine different types of pillows. While an innovative idea, customers least expected to see a menu for pillows. As a result, the hotel ended up wasting resources on things that didn’t matter [8].

This gap between customer expectations and a firm’s understanding can negatively impact service quality.

Gap 2: Management Perception—Service Quality Specification Gap

Gaps between management’s perception of consumer expectations and the firm’s service specifications can affect service quality and arise for several reasons:

It may not be possible to deliver on the expectations reasonably. For example, a customer may expect a car to be serviced in under one hour, but a thorough, good-quality checkup may require longer.

Sometimes, this could be due to a lack of commitment from management – while management may recognize the importance, they may fail to commit to the needed resources.

For example, airlines know they need extra staff during the peak holiday season, but few are willing to commit extra resources and bear extra costs.

Gap 3: Service Quality Specification—Service Delivery Gap

High-quality service is not guaranteed even with established guidelines for performing service well and treating customers correctly. This is because service firms’ employees strongly influence consumer perception of quality, and their performance cannot always be standardized.

Gap 4: Service Delivery—External Communication Gap

Media advertising and communications can significantly influence consumer expectations. Firms that promise more than what can be delivered raise initial expectations, leading to lower perceptions of quality when the promises are not fulfilled.

External communications also influence service quality when companies fail to inform consumers about their special efforts to assure quality—efforts that are not easily visible.

For instance, unless a securities brokerage informs customers about its “48-hour rule” prohibiting employees from buying or selling securities, customers may assume that the brokers probably make all the good deals for themselves.

External communications thus affect consumer expectations and perceptions of the service delivered.

Discrepancies between service delivery and external communications—in the form of exaggerated promises and/or the absence of information about service delivery aspects intended to serve consumers well—can affect consumer perceptions of service quality.

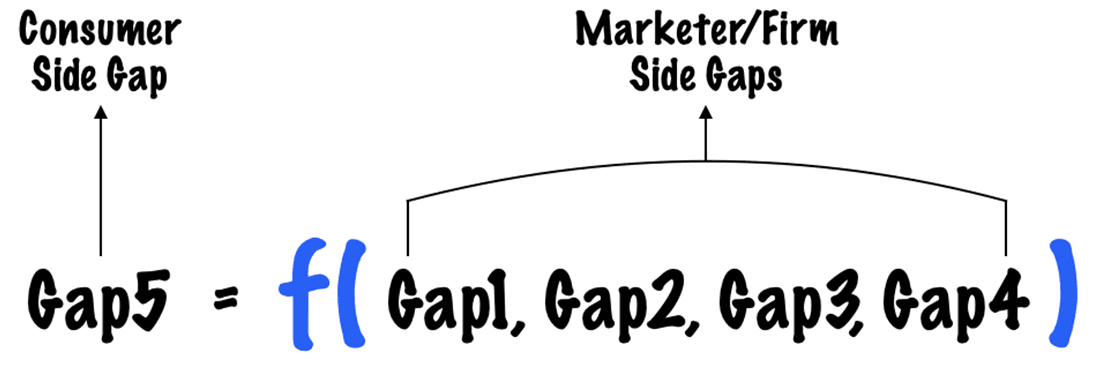

Gap 5: Expected Service—Perceived Service Gap

Key to ensuring good service quality is meeting or exceeding what consumers expect from service. Judgments of high and low service quality depend on how customers perceive the actual service performance in the context of what they expect.

This, in turn, gives rise to Gap 5, a consumer-side gap that is a function of the four previously discussed gaps.

Gap 5 can be favorable or unfavorable from a service quality perspective. For example, the

service delivery—external communication gap (Gap 4) would positively influence consumer perception if the service delivered is better than what a firm communicates.

However, the same level of service delivery may negatively influence another firm that makes better promises in its marketing communication, though both firms have similar pricing.

Formation and evolution of SERVQUAL dimensions of service quality

Focus group studies to identify the above gaps further revealed that consumers use similar criteria to evaluate service quality regardless of service type. Thus, in the original formulation of SERVQUAL, ten dimensions of service quality were identified [4]:

| Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Reliability | Ability to perform the promised service consistently and dependably. |

| 2. Responsiveness | Willingness or readiness of employees to help customers and provide prompt service. |

| 3. Competence | Possession of the required skills and knowledge to perform the service. |

| 4. Access | Ease of contact and approachability of the service provider. |

| 5. Courtesy | Politeness, respect, consideration, and friendliness of the service provider’s staff. |

| 6. Communication | Keeping customers informed in a language they can understand and listening to them. |

| 7. Credibility | Trustworthiness, believability, and honesty of the service provider. |

| 8. Security | Freedom from danger, risk, or doubt. |

| 9. Understanding / Knowing the Customer | Efforts to understand the customer’s needs and provide individualized attention. |

| 10. Tangibles | Physical facilities, equipment, and appearance of personnel. |

Items representing various facets of these ten service-quality dimensions were generated to form the initial item (question) pool for the SERVQUAL instrument.

This process resulted in 97 items (approximately ten items per dimension), each recast into two statements—one to measure expectations about firms in general within the service category being investigated and the other to measure perceptions about the firm whose service quality was being assessed.

The expectation statements formed the first half of the instrument while the corresponding perception statements formed the second half.

In 1988, the 97-item SERVQUAL instrument was further subjected to two stages of data collection and refinement.

The first stage focused on:

- Condensing and retaining only those items capable of discriminating well across respondents having differing quality perceptions about firms in several categories.

- Examining the scale’s dimensionality and establishing the reliabilities of its components.

The second stage analyzed fresh data to re-evaluate the condensed scale’s dimensionality and reliability and further refined it.

As a result, SERVQUAL’s original ten dimensions were collapsed into five. While reliability, tangibles, and responsiveness remained distinct, the remaining seven components collapsed into two aggregate dimensions: assurance and empathy.

Based on this, the 97-item SERVQUAL instrument shrunk to a shorter 22-item instrument that measured customers’ expectations and perceptions along the five dimensions:

| Dimensions | Definition | Items (questions) in scale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Reliability | The ability to perform the promised service dependably and accurately | 4 |

| 2. Assurance | The knowledge and courtesy of employees and their ability to convey trust and confidence | 5 |

| 3. Tangibles | The appearance of physical facilities, equipment, personnel and communication materials | 4 |

| 4. Empathy | The provision of caring, individualized attention to customers | 5 |

| 5. Responsiveness | The willingness to help customers and to provide prompt service | 4 |

In 1991, a follow-up study further refined the wording of SERVQUAL questions, mainly the expectations items [6].

Using SERVQUAL

SERVQUAL measures customers’ expectations and perceptions along five dimensions. For each dimension, four (or five) numbered items (questions) are used to measure scores (see template below).

The instrument is administered twice, first to measure expectations and second to measure perceptions. Each of its five dimensions and 22 items represents core evaluation criteria that transcend specific companies and industries.

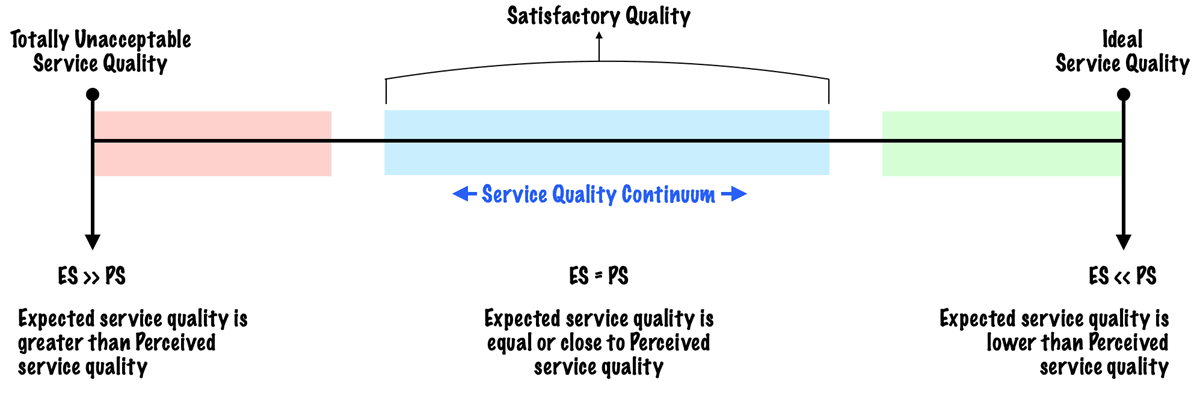

According to SERVQUAL authors, service quality exists along a continuum in customers’ eyes and can range from ideal to totally unacceptable. Somewhere in between that continuum lies satisfactory quality.

The position of a consumer’s perception of service quality depends on the nature of the discrepancy between the Expected Service (ES) and Perceived Service (PS):

Guidelines To Use SERVQUAL

The below guidelines improve SERVQUAL’s effectiveness:

- Use SERVQUAL in its entirety as much as possible. While minor modifications in item wordings (to adapt to specific settings) are acceptable, deleting items can affect the scale’s integrity.

- Context-specific items can supplement SERVQUAL. However, new items must be similar in form (e.g., they should be general rather than transaction-specific).

- SERVQUAL can be supplemented with additional qualitative or quantitative research to uncover the causes underlying the key problem areas or gaps identified by a SERVQUAL study (e.g., along with an employee survey that could suggest what factors lead to good/poor service quality).

- SERVQUAL is more valuable when used periodically to track service quality trends (typically 2-3 times annually).

- Only current or past customers of a firm can participate in SERVQUAL, as meaningful responses to perception statements require them to have knowledge and experience with the firm.

Instructions For Expectation Section

Provide the following instructions to survey participants before they respond to the expectation section of the SERVQUAL questionnaire:

- Based on your experience as a customer of <name of your company>’s services, consider the kind of company that would deliver excellent service.

- Think about the company you would be pleased to do business with.

- Please show the extent to which you think such a company would possess the feature described by each statement.

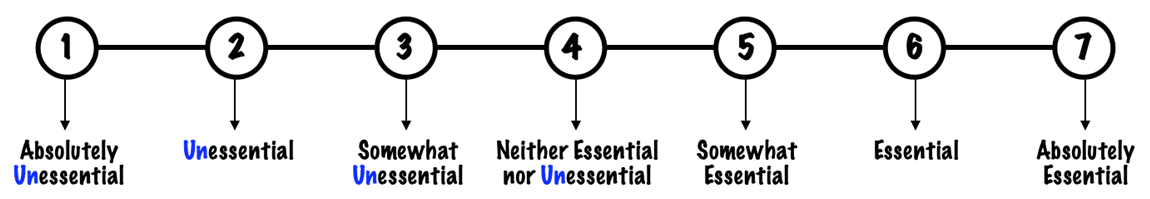

- If you strongly feel a feature is absolutely unessential for excellent service companies, such as the one you have in mind, provide a score of 1.

- If you feel a feature is absolutely essential for excellent service companies, provide a score of 7.

Use a 7-point Likert scale [9] to collect responses:

Let the participants know that there are no right or wrong answers and that the goal is to arrive at a number that accurately reflects their feelings regarding companies that (according to their perception) would deliver excellent quality of service.

Instructions For Perceptions Section

Provide the following instructions to participants before they respond to the perceptions section:

- Each statement in the perception sections relates to feelings about <name of your company>’s service.

- For each statement, please show the extent to which you believe <name of your company> has the feature described by the statement.

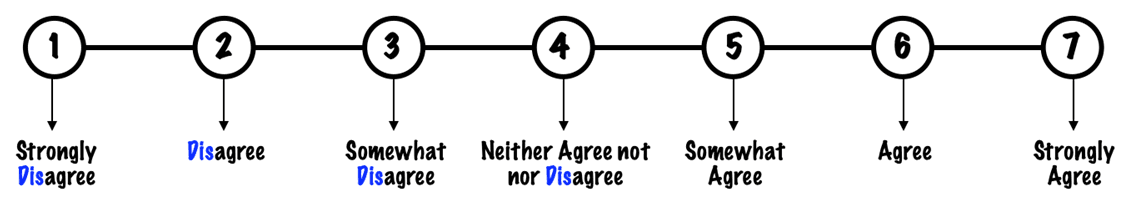

- A score of “1” indicates you strongly disagree that XYZ has that feature.

- A score of “7” indicates that you strongly agree that XYZ has that feature.

Like in the case of expectation items, use a 7-point Likert scale:

Again, let the participants know that there are no right or wrong answers and that the goal is to find a score that best reflects their perceptions of your company’s service.

SERVQUAL Questionnaire Template

Use the 22-point SERVQUAL questionnaire template to capture responses:

| Expectation Survey | Perception Survey | E | P | Gap | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangibility | E1. Excellent companies will have modern-looking equipment. | P1. XYZ company has modern-looking equipment. | |||

| E2. The physical facilities at excellent companies will be visually appealing. | P2. XYZ company’s physical facilities are visually appealing. | ||||

| E3. Employees of excellent companies will be neat-appearing. | P3. XYZ’s company’s employees are neat-appearing. | ||||

| E4. Materials associated with the service (such as pamphlets or statements) will be visually appealing in excellent companies. | P4. Materials associated with the service (such as pamphlets or statements) are visually appealing at XYZ company. | ||||

| Reliability | E5. When excellent companies promise to do something by a certain time, they do so. | P5. When XYZ company promises to do something by a certain time, it does so. | |||

| E6. When customers have a problem, excellent companies will show sincere interest in solving it | P6. When you have a problem, XYZ company shows a sincere interest in solving it. | ||||

| E7. Excellent companies will perform the service right the first time | P7. XYZ company performs the service right the first time. | ||||

| E8. Excellent companies will provide the services at the time they promise to do so | P8. XYZ company provides its services at the time it promises to do so. | ||||

| E9. Excellent companies will insist on error free records. | P9. XYZ company insists on error-free records. | ||||

| Responsiveness | E.10 Employees of excellent companies will tell customers exactly when services will be performed | P10. Employees of XYZ company tell you exactly when services will be performed. | |||

| E.11 Employees of excellent companies will provide prompt services to customers | P11. Employees of XYZ company give you prompt service. | ||||

| E.12 Employees of excellent companies will always be willing to help customers | P12. Employees of XYZ company are always willing to help you. | ||||

| E.13 Employees of excellent companies will never be too busy to respond to customers | P13. Employees of XYZ company are never too busy to respond to your requests. | ||||

| Assurance | E.14 The behavior of employees at excellent companies will instill confidence in customers | P14. The behavior of employees of XYZ company instills confidence in customers. | |||

| E.15 Customers of excellent companies will feel safe in their transactions | P15. You feel safe in your transactions with XYZ company. | ||||

| E.16 Employees of excellent companies will be consistently courteous with customers | P16. Employees of XYZ company are consistently courteous with you. | ||||

| E.17 Employees of excellent companies will have the knowledge to answer customers’ questions | P17. Employees of XYZ company have the knowledge to answer your questions. | ||||

| Empathy | E.18 Excellent companies will give customers individual attention | P18. XYZ company gives you individual attention. | |||

| E.19 Excellent companies will have operating hours convenient to all their customers | P19. XYZ company has operating hours convenient to all its customers. | ||||

| E.20 Excellent companies will have employees who give customer personal attention | P20. XYZ company has employees who give you personal attention. | ||||

| E.21 Excellent companies will have customer’s best interests at heart | P21. XYZ company has your best interests at heart. | ||||

| E.22 The employees of excellent companies will understand the specific needs of their customers | P22. Employees of XYZ company understand your specific needs. | ||||

(Source: Refinement and reassessment of the SERVQUAL scale, 1991 [6])

Analyzing The Responses

Analysis of SERVQUAL data can take several forms.

One method is item-by-item analysis, in which the difference is calculated at each question level—for example, P1 – E1, P2 – E2, etc. This method develops a granular item-level picture to identify areas of improvement.

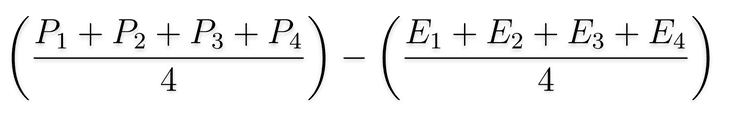

Another broader method is a dimension-by-dimension analysis. For example, an analysis across the tangibility dimension would be:

Here, P1 to P4 and E1 to E4 represent the four perception and expectation statements relating to the tangibility dimension. This method provides a dimension-level view of gaps that firms can use to improve a broader set of processes.

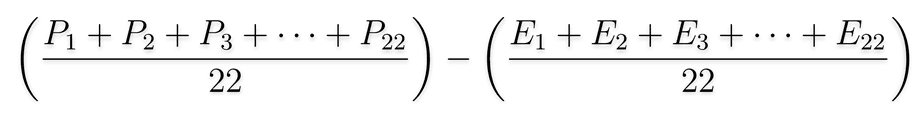

A third method is to compute the overall gap (also known as the SERVQUAL gap) as a single measure of service quality:

This provides a high-level view of the gap between expectation and perception.

Criticisms and Limitations of SERVQUAL

Despite its popularity and widespread application, SERVQUAL has been subjected to several theoretical and operational criticisms, some of which are briefly explained [10]:

Paradigmatic objections

SERVQUAL is based on a disconfirmation rather than an attitudinal paradigm. Some experts believe perceived service quality’s complexity and subjective nature are best captured by attitude rather than the gap between expectations and specific service encounters.

Failure to build on established theories

SERVQUAL fails to draw on established economic, statistical, and psychological theories.

Accuracy of Gaps Model

There is little evidence that customers assess service quality through perception-expectation gaps. Some experts have argued that consumers form expectations during or after service experiences rather than before.

Social norms can also induce bias into expectation scores as respondents may feel motivated to adhere to an “I-have-high-expectations” norm.

Focus on Process but not Outcome

Because SERVQUAL focuses on the service delivery process rather than the service encounter’s outcomes, some critiques argue that the quality’s outcome is not adequately accounted for.

Dimensionality

Questions have been raised on the number of SERVQUAL dimensions and their stability from context to context. Some critics argue that these dimensions aren’t fixed for every situation and that their number can vary depending on the context.

Additionally, the items used to measure the dimensions may not always align with what one might expect beforehand.

Additionally, SERVQUAL dimensions are also correlated, which means improvement in one area may impact others. This underscores the complexity of effectively assessing and enhancing service quality.

Expectations

The term “expectation” can have different meanings depending on the consumer. For example, when providing an expectation score, respondents may be using any one of six interpretations:

- Service attribute importance: Customers may rate the expectations statements according to the importance of each.

- Forecasted performance. Customers may rate using the scale to predict the performance they would expect.

- Ideal performance: The optimal performance; what performance “can be.”

- Deserved performance. The level of performance that customers, in light of their investments, feel should be.

- Equitable performance. The level of performance customers feel they ought to receive given a perceived set of costs.

- Minimum tolerable performance. What performance “must be.”

Each interpretation is somewhat different and can induce variance in SERVQUAL expectation scores.

Item composition

Four or five items (questions) may not be adequate to capture the variance within, or the context-specific meaning of, each SERVQUAL dimension. While context-specific items can be used to supplement SERVQUAL, authors have cautioned that the new items should be similar in form to the existing items.

Moments of Truth

Many services are delivered over several moments of truth (MoTs) or encounters between service staff and the customer. Consequently, customers evaluate service quality by referencing multiple encounters.

In SERVQUAL, service quality is seen as a global construct, not directly connected to particular incidents. This fails to account for several MoTs.

Likert Scale Points

While not specific to SERVQUAL, the seven-point Likert scale has been criticized on several grounds. Most notably, a lack of verbal labeling for points two to six may cause respondents to overuse the extreme ends of the scale.

Another area of concern is the respondent’s interpretation of the meaning of the midpoint of the scale, which can vary from “don’t know” to “do not feel strongly in either direction” to “do not understand the statement”.

Two administrations

Because SERVQUAL, with its 22 responses, has to be administered twice, respondents can become bored and sometimes confused by the administration of E and P versions. This can affect data quality.

Some experts argue that when expectations and experience evaluations are measured simultaneously, respondents tend to indicate that their expectations are greater than they actually were before the service encounter.

Additionally, customers who had a negative experience with the service tend to overstate their expectations, creating a larger gap; customers who had a positive experience tend to understate their expectations, resulting in smaller gaps.

Summary

In today’s service-dominated world, companies invest record amounts of money to develop customer relationships—from traditional loyalty programs to customer relationship management (CRM) technology to general service quality improvements.

Many of these initiatives, however, end up in disappointment. Knowing what matters to customers can go a long way toward optimizing resource deployment.

SERVQUAL’s impact in the domain of service quality measurement is widely accepted. Despite criticisms, even its major critics have acknowledged its popularity.

Sources

1. “Share of economic sectors in the global gross domestic product (GDP) from 2012 to 2022”. Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/256563/share-of-economic-sectors-in-the-global-gross-domestic-product/. Accessed 22 Feb 2025.

2. “Effect of Expectation and Disconfirmation on Postexposure Product Evaluations: An Alternative Interpretation”. Richard L. Oliver, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232487404_Effect_of_Expectation_and_Disconfirmation_on_Postexposure_Product_Evaluations_An_Alternative_Interpretation. Accessed 22 Feb 2025.

3. “Service Quality: New Directions in Theory and Practice”. Roland T. Rust and Richard L. Oliver), https://www.amazon.com/dp/0803949200. Accessed 23 Feb 2025.

4. “A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and its Implication for Future Research (SERVQUAL)”. A Parsu Parasuraman, Valarie A. Zeithaml and Leonard L Berry, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225083670_A_Conceptual_Model_of_Service_Quality_and_its_Implication_for_Future_Research_SERVQUAL. Accessed 21 Feb 2025.

5. “SERVQUAL: A multiple-Item Scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality”. V. A. Z. a. L. L. B. A Parsu Parasuraman, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225083802_SERVQUAL_A_multiple-_Item_Scale_for_measuring_consumer_perceptions_of_service_quality. Accessed 23 Feb 2025.

6. “Refinement and reassessment of the SERVQUAL scale”. A Parsu Parasuraman, Valarie A. Zeithaml and Leonard L Berry, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304344168_Refinement_and_reassessment_of_the_SERVQUAL_scale. Accessed 23 Feb 2025.

7. “Service quality in product development companies: a study using the SERVQUAL tool”. Sandra Miranda Neves, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322371898_Service_quality_in_product_development_companies_a_study_using_the_SERVQUAL_tool. Accessed 23 Feb 2025.

8. “Redefining customer service”. UDaily – University of Delaware, https://www1.udel.edu/udaily/2015/may/gore-lecture-050115.html. Accessed 24 Feb 2025.

9. “What is a Likert scale?”. Survey Monkey, https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/likert-scale/. Accessed 24 Feb 2025.

10. “SERVQUAL: Review, Critique, Research agenda”. European Journal of Marketing, Francis A Buttle, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235313579_SERVQUAL_review_critique_research_agenda. Accessed 25 Feb 2025.

11. “A Review and Critique of Research Using Servqual”. Lisa Coulthard, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322814942_A_Review_and_Critique_of_Research_Using_Servqual. Accessed 26 Feb 2025.