The only thing certain about business environments is uncertainty. A risk-intelligent enterprise must proactively address risks, leverage opportunities, and position itself to respond rapidly as the landscape evolves. Yet, most organizations often struggle to achieve the strategic flexibility and agility required to be in that golden spot.

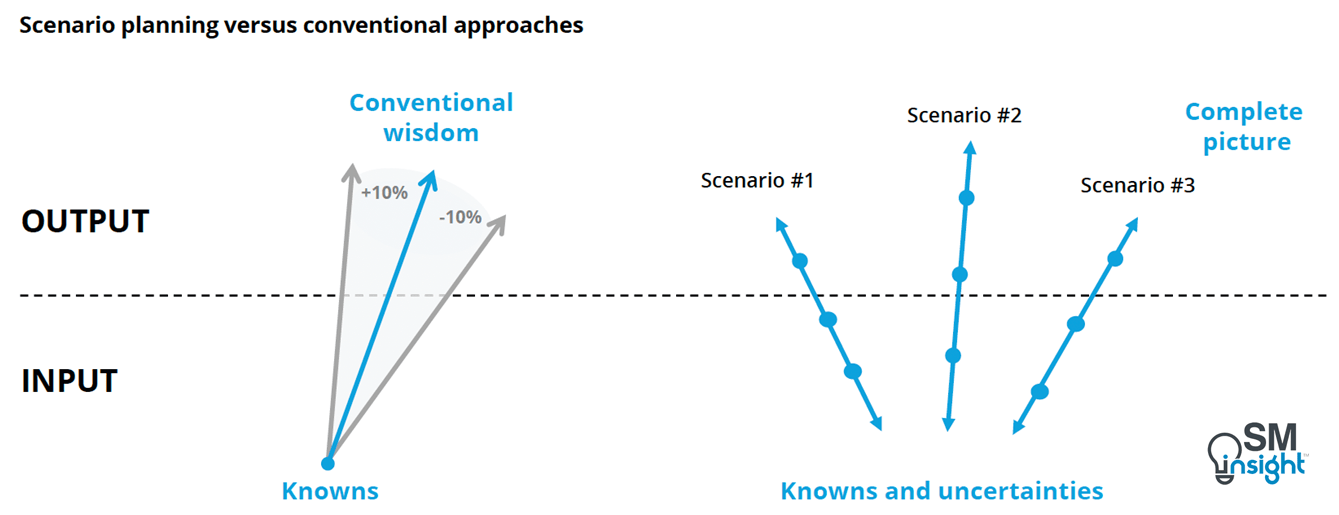

Conventional strategic analysis tools address uncertainty to a limited extent. This is because they assume future conditions to be an upward or downward extension of the present.

Decision-making is limited to making incremental adjustments in current factors such as budgets, headcounts, and resource allocations or, analyzing a limited choice-set of responses. This approach tends to underestimate and mischaracterize risks.

Scenario planning is a powerful tool in the strategist’s armory that is used to navigate extreme events. It enables organizations to steer a course between the false certainty of a forecast and the confused paralysis that often strikes in troubled times.

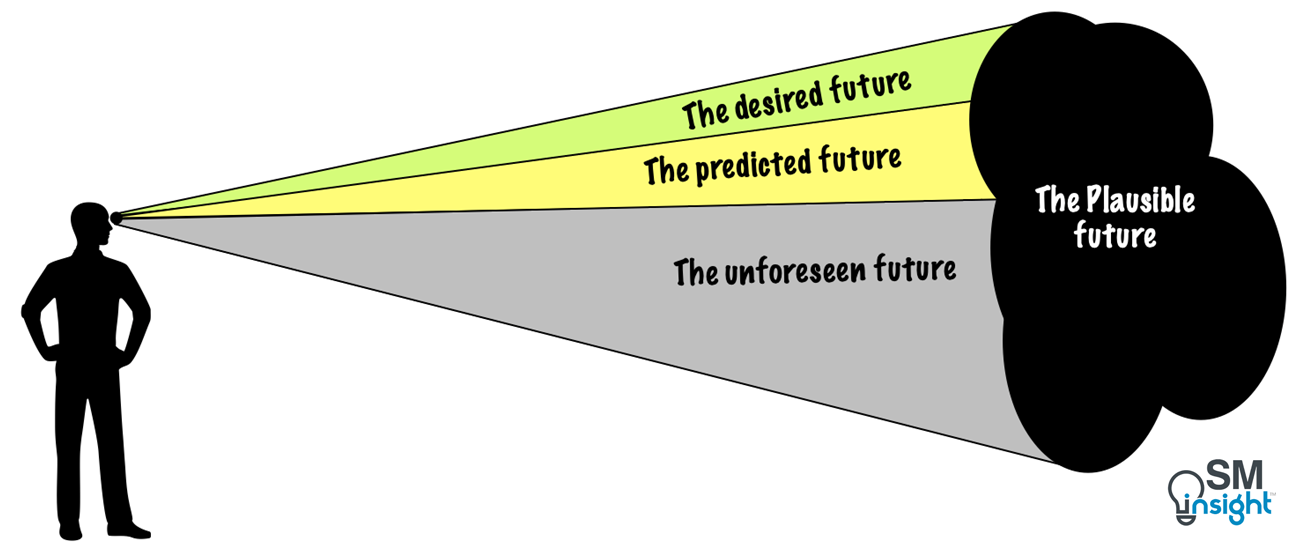

The future can be very different from the one forecasted or desired. Scenario planning helps organizations uncover changes triggered by unforeseen events and prepare for many different possibilities

Scenario planning helps organizations see risks and opportunities more broadly, imagine potential futures and alternative scenarios that might challenge their assumptions, and identify threats that may otherwise go undetected.

At the high level, scenario planning is the process of creating vivid mental pictures of the potential but unknowable future by identifying the current, as well as emerging factors that can influence those future states. It allows organizations to develop strategies that are better aligned with what the future may bring.

Origin of scenario planning as a tool

The roots of scenario planning belong to the domain of military strategy, having been used throughout history. However, its modern developments can be traced back to defence analyst Herman Kahn who is referred to as “the father of the modern Scenario Planning” [1].

Working at the Rand Corporation in the late 1940s after WWII, Kahn put forth a technique known as “future-now thinking” that combined detailed analyses with imagination to produce reports as though people wrote them in the future [2]. In 1961, Kahn left RAND to help found the Hudson Institute, where he eventually shared his ideas with Pierre Wack, an executive from Royal Dutch Shell.

Around the same time, the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) began offering long-range scenario planning for businesses and was among the first to formalize the technique and give it broad utility in decision-making by businesses and governments [3].

In the early 1970s, Wack applied Kahn’s ideas in the business world to prepare Shell’s response as oil-rich nations of the Middle East began to assert themselves on the world stage. During the price shocks induced by the 1973 OPEC oil embargo [4], Shell was able to ride the crisis out much better than its competitors [5].

The Shell exercises marked the birth of scenario planning as a strategic tool for business managers. In the 1970s, widespread dissatisfaction with existing planning tools and the idea that businesses could make better use of the non-rational side of human nature led to a rapid rise in the tool’s popularity. It has since been used by some of the world’s largest corporations, including Motorola, Disney and Accenture.

The appeal of scenario planning further increased in the wake of the 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center (WTC) and the greater perceived uncertainty of the 21st century. Incidentally, the use of scenario planning prompted the New York Board of Trade to build a second trading floor outside the WTC in the 1990s – a decision that kept it going after the attacks [6].

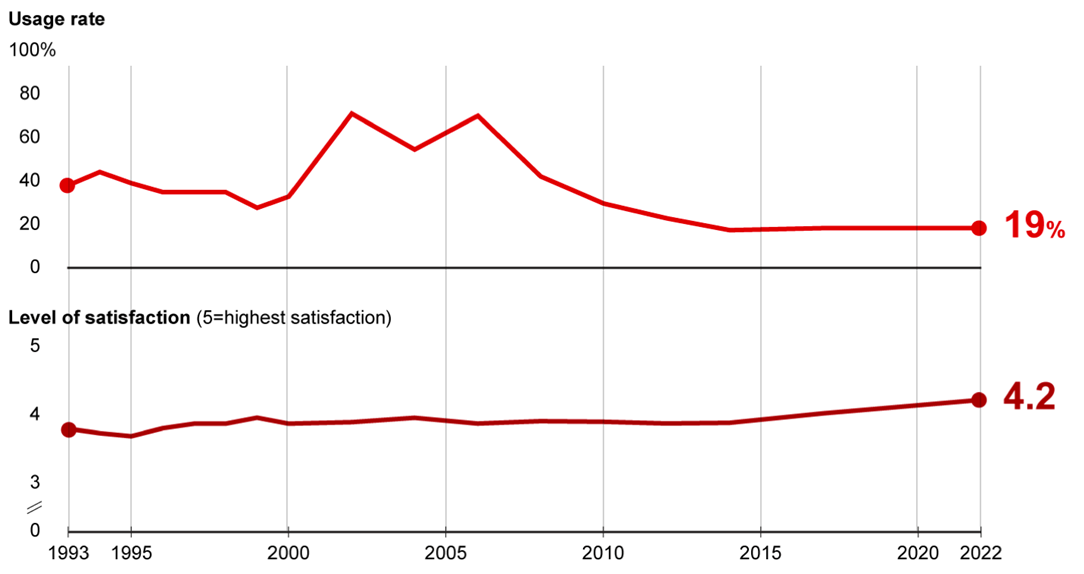

According to Bain & Company’s annual survey of management tools, fewer than 40% of companies used scenario planning in 1999, but by 2006, its usage had risen to 70%. While the tool remained popular during the 2008 financial crisis, there has since been a decline in its popularity which remains at 19% as of 2022:

(Source: Bain & Company [7])

What can scenario planning do?

Scenario planning, when used as a strategy tool, has three features that make it particularly powerful for understanding uncertainty and developing strategy [8]:

1. It expands thinking

Scenario planning helps develop a wide range of possible outcomes, each backed by the sequence of events that would lead to them. This is particularly valuable to break the human tendency to believe that the future will resemble the past and that change will occur only gradually.

By demonstrating how and why things could quite quickly become much better or worse, scenario planning helps improve preparedness for a range of possibilities. It forces thinkers to challenge the validity of assumptions that shaped the past which leads to surprisingly compelling answers.

The human tendency to depend on past events was powerfully illustrated in the 2008 global meltdown, where financial modelers used data going back only a few years and were therefore unprepared for what followed.

Scenarios force firms to stop and ask: “What would have to be true for the following outcome to emerge?” As a result, they find themselves testing a wide range of hypotheses and their underlying drivers. They learn which drivers matter and which do not—and what will affect those that matter enough to change the scenario.

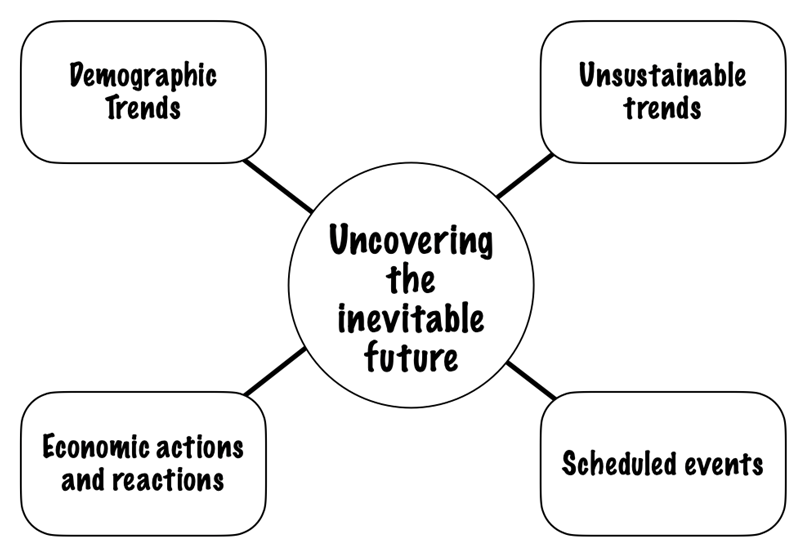

2. It uncovers inevitable or near-inevitable futures

Scenario planning helps unearth outcomes that are inevitable consequences of events that have already happened or of trends that are already well-developed. The essence of this is best captured by the saying: “If it has rained in the mountains, it will flood in the plains.”

There are, broadly, four kinds of predetermined outcomes that scenario planning helps unearth: demographic trends, economic action and reaction, the reversal of unsustainable trends and scheduled events:

Demographic trends are long-term effects of changing demography, such as changes in population size and structure. The effects of these trends can be far off (social security in the U.S. or the impact of the single-child policy in China).

While these effects are generally ignored in the short term, when the trends grow near, their effects can be very powerful.

Economic actions and reactions –business environments are governed by the laws of economics. For example, if demand shoots up, prices will too – which will limit demand and drive increasing supply – with the result that demand, prices, or both will drop.

As in physics, every economic action has a predetermined reaction. These reactions are often ignored in business strategy. When uncovered through scenario planning, however, they generate powerful insights.

Unsustainable trends – businesses often base their plans on extrapolated future trends that can be unsustainable. Economies are fundamentally cyclical. The appearance of even a genuine new paradigm almost always results in a speculative bubble.

Railroads and radio, for example, were hailed as “new paradigms” that led to investment bubbles. More recently, Metaverse technologies, with their promise of “virtual cities” and “virtual offices” attracted billions of investment dollars but failed to gain popularity while costing people their jobs, investors their money, and people their time [10].

By questioning the fundamentals, scenario planning forces businesses to ask the question – “how long can this be sustained?” – opening eyes to the possibility of a break in the trend.

Scheduled events are the ones that fall beyond typical corporate planning horizons (for example: trade agreement expiry or renegotiation, climate change policy updates). Although not beyond the realm of common knowledge, they tend to be overlooked in planning because they fall beyond the next 12 to 18 months. Scenarios account for such scheduled events that could have a big impact over a longer time frame.

3. It protects against ‘groupthink’ and challenges conventional wisdom

The power structure in most companies inhibits the free flow of debate. People generally tend to align with what the most senior person in the room has to say.

The problem is further aggravated by what is known as the status quo bias – when large sums of money and careers are invested in the core assumptions underpinning the current strategy, challenging those assumptions becomes difficult.

Scenarios provide a less threatening way to lay out alternative futures in which assumptions underpinning current strategy may no longer be true. They provide people with a political “safe haven” for contrarian thinking.

Difference between Scenario, Forecast & Vision

Enduring companies have clear plans for how they will advance into an uncertain future.

They use scenarios, forecasts, and visions – all of which try to paint a picture of the future, but their purpose is very different and there are important differences.

A vision is an image of the aims and goals that a business must have before it sets out to reach them. It must be bold and ambitious and must rev up the entire organization. It is usually conveyed in a dramatic and enduring way. However, vision represents the desired future and not necessarily the probable one.

Forecasts attempt to predict the near-term future with an emphasis on past and current data. Under stable conditions and within short timeframes, these are both necessary and powerful. They provide the needed risk reduction and certainty to be able to make decisions. However, they become more complex and lose relevance as one looks further into the future.

In the real world, organizations must identify potential risks and opportunities and prepare for not one but many possible futures. At the same time, they cannot explore every possible future. This is where scenario planning comes in. Through skillfully crafted scenarios, they

reduce a large amount of uncertainty to a handful of plausible alternatives that together capture the most relevant uncertainty dimensions.

The differences between the three are shown in summary:

| Scenarios | Forecasts | Visions |

|---|---|---|

| Possible, plausible versions of future | Probable versions futures | Desired version of the future |

| Uncertainty based | Based on the past and present variables | Purpose and value-based |

| Illustrate risks | May hide risk | Hides risk |

| Based on qualitative and quantitative data | Based on quantitative data | Usually qualitative |

| Suited for strategic decision-making | Suited for tactical Decision-making | Suited to energize the organization’s workforce |

| Not used regularly | Used regularly | Once formulated, visions don’t change often |

| Best suited for medium to long-term perspective | Best suited to short term perspective | Functions as trigger for voluntary change |

| Deals with medium to high uncertainty | Deals with comparatively low degree of uncertainty |

Building and deploying scenarios

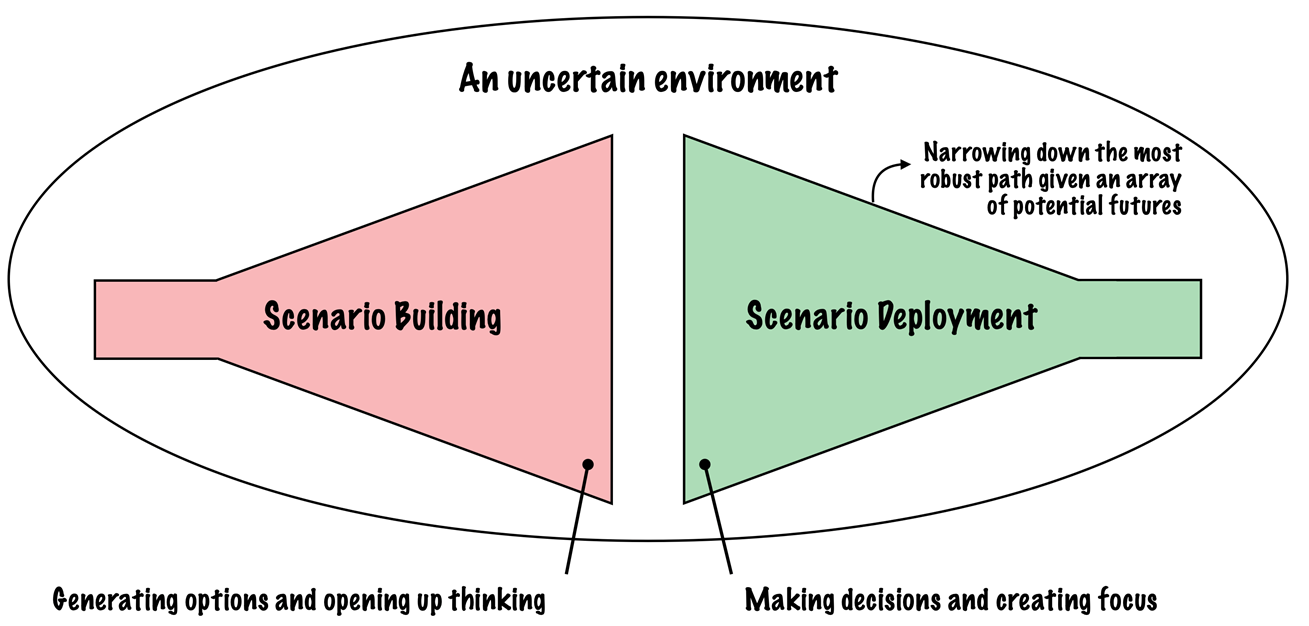

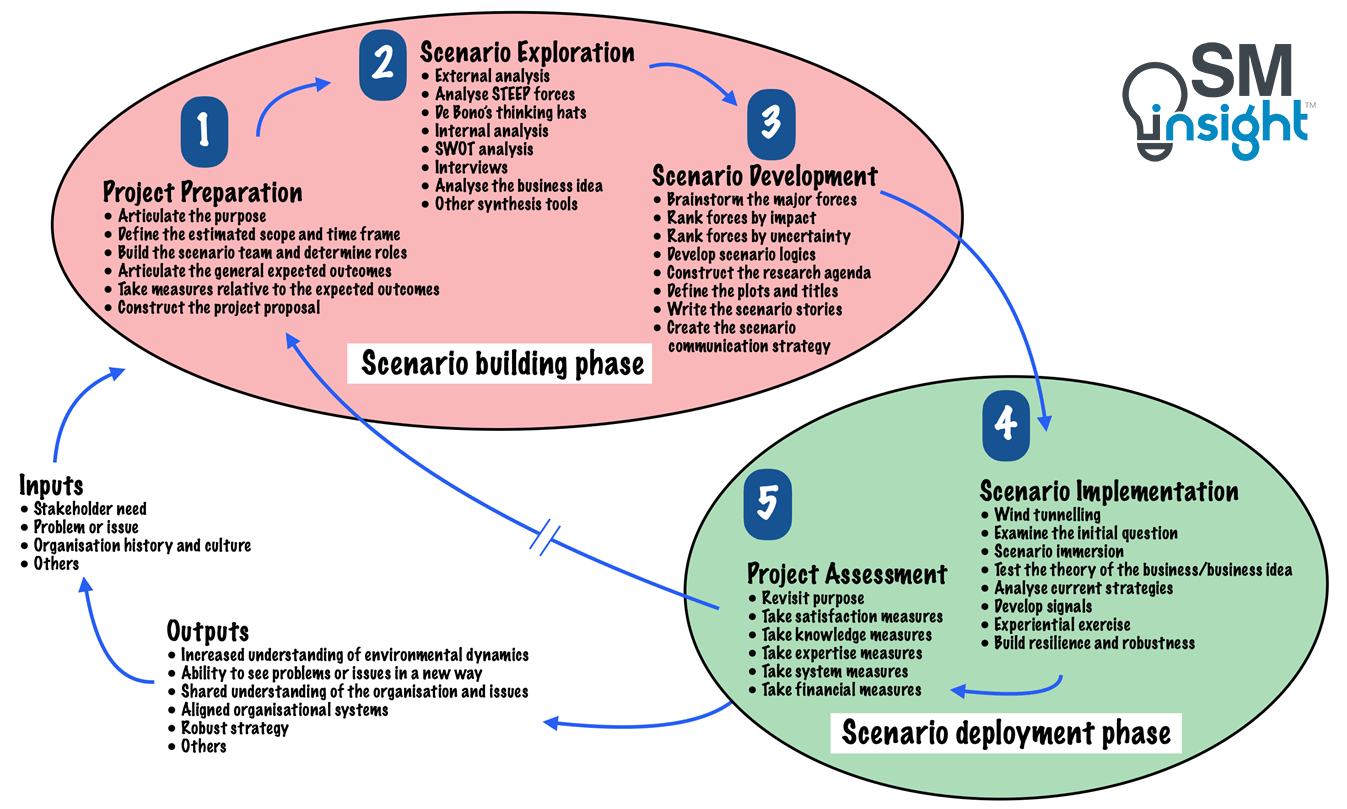

Scenario planning as a system within the organization can be divided into two parts: scenario building and scenario deployment:

Scenario building deals explicitly with the conduct of data gathering, analyzing, synthesizing, and eventually the construction of scenarios. It is about opening up the organization’s thinking and expanding the frame to include a wider range of possibilities.

Scenario deployment centres around how to use the generated scenarios in ways that lead to outcomes. It deals with improving decision-making, shifting the thinking of managers, reframing decision-making processes, and examining numerous organizational issues in the context of each scenario.

While scenario building is characterized by divergent and challenging thinking, deployment is characterized by convergent thinking, where options are reduced through decision-making.

The main steps in conducting a scenario planning exercise can be captured in five phases:

Phase 1: Project preparation

The goal of this phase is to establish a formal proposal that lays out the key elements that become the basis for everything else to follow. It involves building agreement among the project leader and organizational decision-makers on five critical items:

- The purpose and question of the scenario project

- Its estimated scope and timeline

- Building a scenario team and defining each of their roles

- Outlining the expected outcomes

- Defining measures to assess achievement and success

Articulating the purpose of the scenario project

Scenario planning usually begins with the identification of a problem. The best way to start is by listening to key people talk about situations they face, becoming oriented to their problems, and gathering perceptions of the problem the project is expected to address.

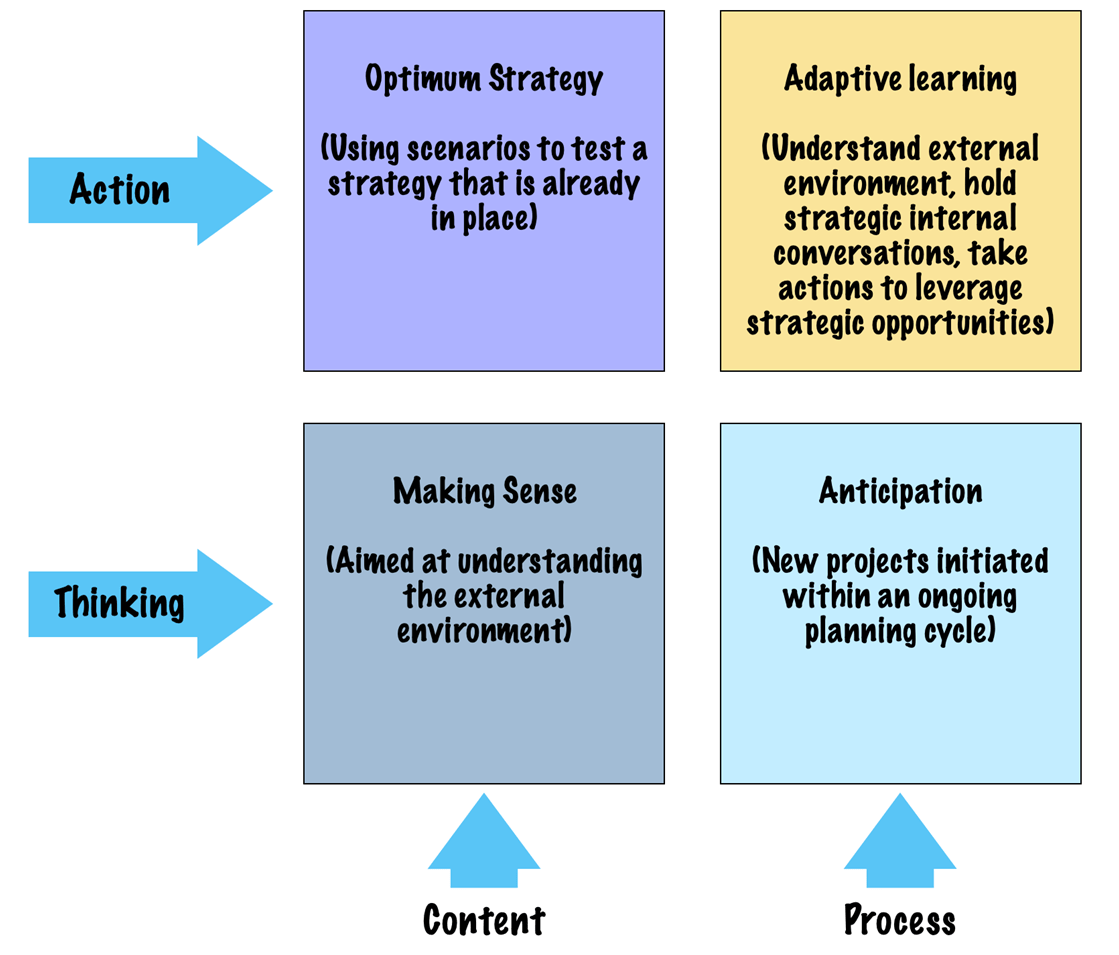

There are four distinct purposes for engaging in scenario planning that flow logically from the interactions between content and process on one continuum, and thinking and action on the other:

- Making Sense: these are first-generation scenarios whose primary purpose is not to impel action but to gain understanding of, and insight into the external environment.

- Optimum strategy: These are scenarios used to test a strategy already in place. They seldom lead to strategic learning or insights due to difficulties in shifting away from predictive thinking and an inability to entertain multiple possibilities.

- Anticipation: These are new projects initiated within a continual, ongoing scenario planning cycle. They are analogues to continuous quality improvement. Firms that pursue scenario planning with this purpose prevent groupthink by generating new ideas, preventing fragmentation, and developing a collective understanding.

- Adaptive learning: is an advanced form of scenario work that allows organizations to learn and adapt from their own experience and navigate the turbulent business environment. Such organizations simultaneously develop a better understanding and awareness of uncertain elements in the environment and improve the quality of the internal strategic conversation.

Asking the question

A clear question helps examine a range of possible environments in which strategic choices can play out. It helps explore a variety of answers and their implications. Some of the sample questions to consider before initiating a scenario planning project include:

- How can the current value proposition be retained in a high-change environment?

- Is there a need to introduce a completely new product or service?

- How can current strengths be leveraged to improve customer value and efficiency?

- What are the major technological advances that the organization may not have thought about?

The scenario project’s purpose and the question it aims to address must be documented in the project proposal.

Estimating the scope and time frame

A scenario project proposal must consider the amount of time and resources the organization is willing to invest in the project, deadlines that may be relevant, and how far into the future the scenarios will reach (the time horizon).

Depending on the time horizon of the scenario, factors such as political cycles, technological shifts etc., can provoke strategic insights.

The project timeline must account for interviews, initial data gathering, scenario-building workshops and workshops to consider their implications. It is important to allow space between the workshops for participants to reflect on and absorb ideas and information. Projects typically require five to nine weeks of commitment at a minimum.

Building the scenario team and defining roles

Having a mix of the right people is critical to a scenario project’s success. It is important to include those who will ultimately use the scenarios along with representatives from each level of the company.

In the project preparation phase, important stakeholder groups and internal leaders at all levels of the organization must be identified, individuals with a high degree of organization knowledge must be recruited, and the scenario team must be assembled.

Below are some of the typical roles in a scenario team:

- Project leader: responsible for directing the scenario project. Must have expertise in scenario planning systems and significant experience in business processes and change interventions.

- Team members: should include people from each level of the organization so that the team is cross-level and cross-functional. These are the people responsible for developing the detailed scenario storylines during workshops and may be split into sub-teams for developing each scenario.

- Coordinator: responsible for convening the group, managing schedules, reserving spaces and locations for scenario work, creating internal mechanisms for the scenario team to communicate, and performing administrative functions.

- Remarkable people: because scenario planning is designed to stretch the organization’s thinking, having people with diverse backgrounds and expertise is important. “Remarkable people” are those with completely different outlooks or mental models than the ones in an organization with an ability to think unconventionally.

Former scenario consulting firm – Global Business Network (now part of Deloitte) is known to include musicians, artists, bench scientists, and other people from a wide range of backgrounds in scenario planning teams to provide alternate perspectives [11] [12].

Articulating expected outcomes

While time spent on clarifying the initial purpose provides a general idea of what is expected, stating the outcome drives additional conversations around specific expectations.

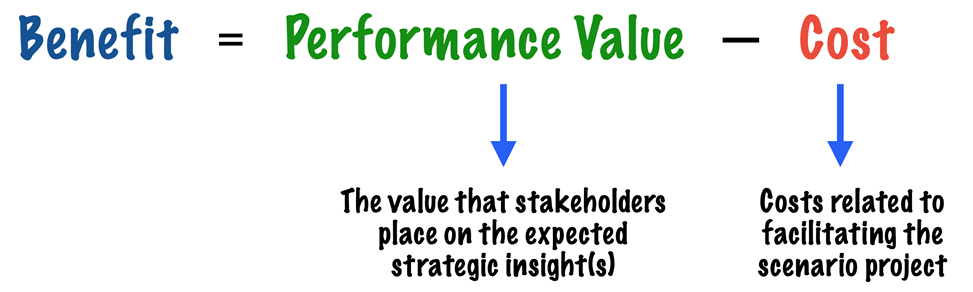

Defining measures to assess the success of outcomes

Knowing precisely how to measure the effects of scenario projects can be tricky, however, estimates can be made based on how scenario planning benefits the organization.

Estimates of savings due to anticipating major business discontinuities, profits gained through strategic insights, or both, can and should be part of the scenario project. A cost/benefit model is a simple tool for accessing the financial benefits of a scenario project:

Other common outcomes of the scenario project include:

- Individual and organizational learning

- Improved decision making

- Stronger communication systems

- Shared mental models of the internal and external environments

- Heightened organizational performance

- Greater organizational agility

- Stronger ability to fit in with the environment

- Deeper anticipatory capacity

- Increased strategic insights

Each of these domains has related measures that, based on relevance, can be assessed at the start and again at the end of a scenario planning project.

Phase 2: Scenario Exploration

This phase of the scenario system focuses on analyzing an organization’s environment. The approach is based on the purpose and questions identified in the project preparation phase and is divided into two parts – external analysis and internal analysis:

External analysis

The external analysis marks the start of a scenario project and requires getting up to speed with the general industry, looking for trends, key factors, and other forces that have an obvious influence on the industry.

The goal is to expand assumptions, beliefs, and possibilities evident in the industry or environment being studied. Information gathering, both at a general level as well as about specific issues under consideration plays a crucial role in this step.

Two skills are essential: first, an ability to adapt scenarios continuously based on evolving world data, and second, maintaining an awareness of various biases in the data and preventing their influence on conclusions.

While there are many approaches to external analysis, three tools particularly stand out:

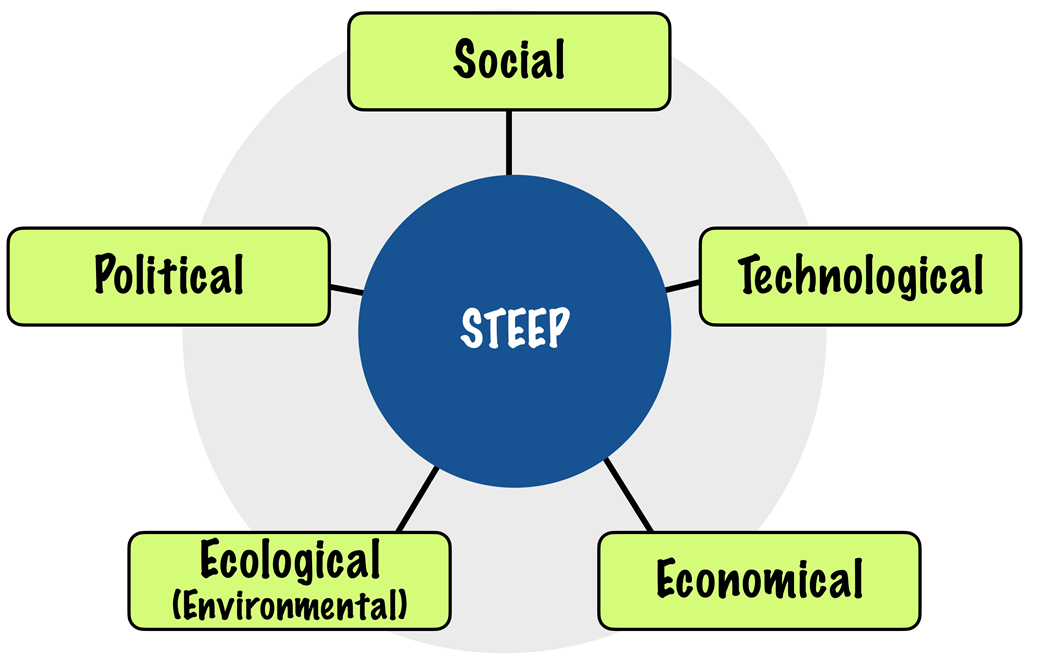

- STEEP Forces

- De Bono’s thinking hats

- SWOT analysis

STEEP Forces

Very similar to PEST / PESTEL analysis [13], STEEP accounts for the broad trends, forces, and changes beyond the boundaries of the firm that may impact its market and operations. STEEP stands for social, technological, economic, ecological, and political factors and is a structured, logical, and effective way to begin an external analysis:

(Source: Strategic Management Insight [13])

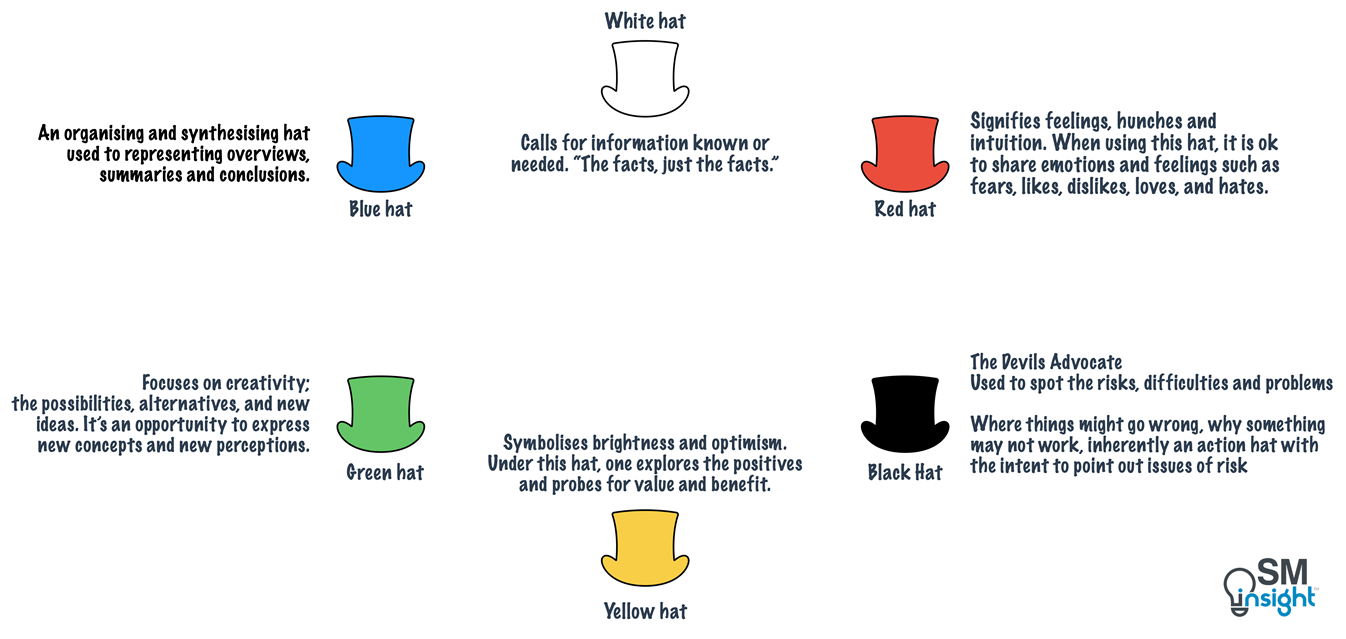

De Bono’s thinking hats

Also known as Six Thinking Hats or Six Hats [14], it is a parallel thinking process that is particularly useful for analyzing complex issues. When people think about complex issues, they are overcrowded with emotions, logic, data, hopefulness, and creativity all of which are too much to make sense of at once.

By separating the thinking process into six clear functions and roles, the six-hat technique helps people become more productive, focused, and mindfully involved. Each of the hats’ role is represented with a color as shown:

While the six-hat technique can be used at any time during the scenario project, they are most helpful when soliciting and capturing initial reactions and comments about the issue.

Discipline and timing are critical to using the six-hat technique effectively. When individuals are asked to think according to a specific hat, they must stay with the hat’s perspective and represent that viewpoint. If people are allowed to derail, they revert to their original, comfortable perspective, and the project gets more of the same.

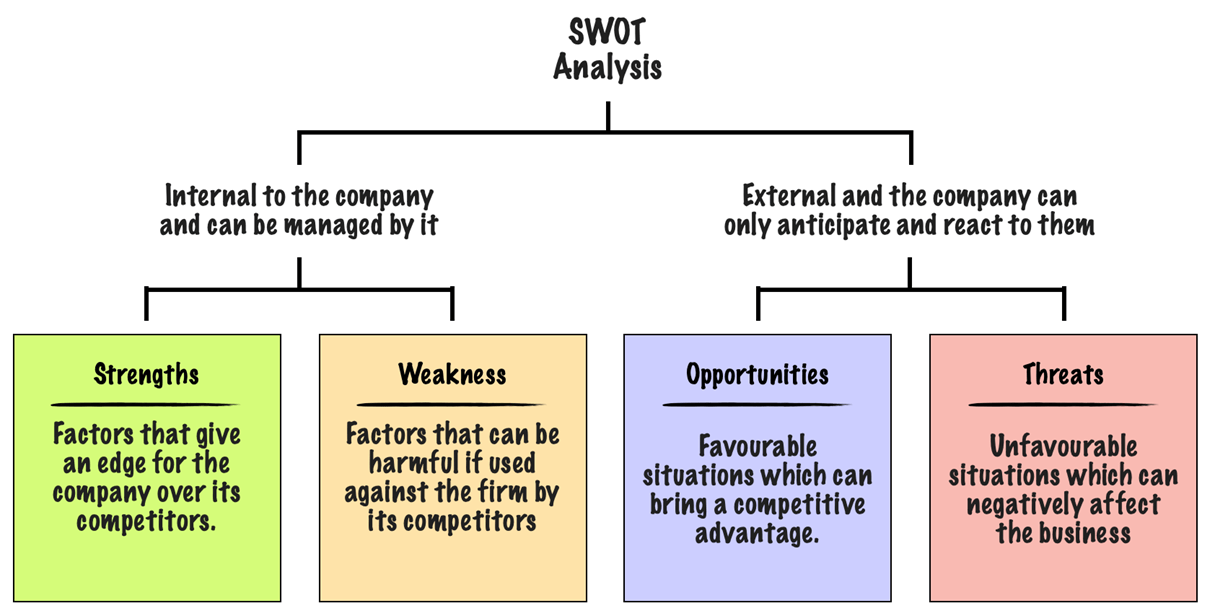

SWOT Analysis

SWOT analysis is a strategic audit tool that takes both internal and external perspectives to distill the findings into critical organizational strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats:

In a scenario project, insights from a SWOT analysis are very useful in understanding the organization and its internal position which can increase the relevance of scenarios when inserted into the narratives developed later.

A disadvantage of SWOT analysis is that it forces dichotomies – an item that falls under the strengths category can often be argued as a weakness as well, and it could be both depending on the contextual circumstances. This dilemma provides an appropriate opportunity to use De Bono’s thinking hats to consider alternate perspectives.

Another common oversight when using SWOT is that the strengths and weaknesses relate to the internal environment, and the opportunities and threats relate to the external environment. When this internal/external distinction is not made, a SWOT analysis can be misleading.

Interviews

Interviewing individuals or groups of people in an organization is a detailed process that requires commitment and skill. Insights generated from interviews are critical to scenario planning as they reveal opinions, facts, experiences, beliefs, organizational symbols, history, and more.

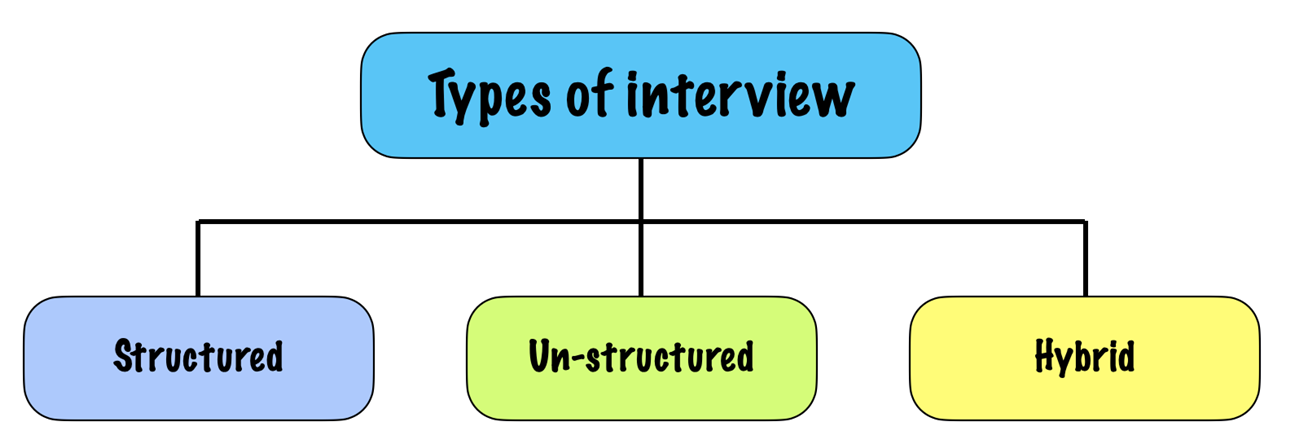

Most importantly, interviews reveal what managers and executives are concerned about. Evoking, addressing, and highlighting these concerns is crucial for scenarios to be effective. Interviews follow three formats:

Structured interviews follow a predetermined list of questions and can be scripted so that each interviewee is asked the same questions. Unstructured interviews follow a casual approach, more like a conversation, where content can be expanded to cover a wide range of subjects and questions.

Hybrid interviews are a combination of both and are best suited for scenario planning. There are seven categories of questions a scenario interview questionnaire must address to surface the strategic agenda of decision-makers:

| Category of Question | Example |

|---|---|

| 1. Clairvoyant | If you could speak with an [industry] oracle from [year], what three things would you like to know about the [organization]? |

| 2. An optimistic scenario | If the [organization, industry] were thriving, growing, and moving in a genuinely positive direction by the year [year], what would be true of it? |

| 3. A pessimistic scenario | If the [organization, industry] were to collapse by [year], what might have caused the collapse and why? |

| 4. Inheritances from the past | What has surprised you (pleasantly or unpleasantly, specifically, or generally) about the [organization, industry] in recent years? |

| What have been some of the memorable “turns” and why? | |

| 5. Important decisions ahead and priorities | What are the major challenges to be faced by [organization, industry, etc.] professionals in the next five years? |

| What are the obstacles to be overcome that keep you awake at night? | |

| 6. System constraints and changes needed | What would hinder the field from moving past these obstacles? |

| What forces could constrain the [e.g., organization and industry]? | |

| 7. Epitaph | If your program/organization was in the danger of being completely cutout, what would be your argument to keeping it going? |

The goal of an interview is to become familiar with the mental models (values, beliefs, assumptions, experiences, hopes, and dreams) of a cross-section of the organization. While the seven questions are a tool for accomplishing this, to be effective, establishing good relationship with each interviewee is critical.

Other data collection methods

Three other data collection methods which are useful in understanding organizational dynamics are questionnaires, observations, and existing data.

Questionnaires allow the collection of data from a large number of people, across locations, in a relatively efficient manner.

Observing people perform their work functions is yet another way which can yield a great deal of qualitative and quantitative data. However, expertise and experience are needed to be unobtrusive and avoid changing how the individual being observed performs work.

Existing data such as previous uses of scenario planning and their outcomes, other planning tools that have been used, recent change initiatives, financial and performance data, employee survey data, and customer data are some more examples of useful data pools for scenario planning.

Analyzing the organization’s business idea

According to Peter Ducker, every organization has a theory of business [16], a set of assumptions that shapes its behavior, dictates its decisions about what to do and what not to do, and defines what the organization considers meaningful.

These are assumptions about its values and behaviors, markets, customers and competitors, technology and its dynamics, strengths, and weaknesses. These are assumptions about what a company gets paid for.

There are four critical aspects of an organization’s theory of the business, that from a diagnostic perspective, are important to know at the start of a scenario planning exercise:

- An organization’s assumptions about its environment, mission, and core competencies must fit with its reality.

- Those assumptions must fit with each other.

- The theory of business must be known and understood throughout the organization.

- The theory of the business must be tested constantly.

To answer these questions, it is useful to conduct a workshop dedicated to understanding the organization’s theory of the business/business idea.

Phase 3: Scenario Development

Scenario development involves conducting workshops where participants challenge each other’s viewpoints and set the foundation for a shared mental model of the organization and its environment. The goal of this phase is to develop two to four relevant, plausible, and challenging scenarios.

Key terms and approaches to scenario development

Knowledge of some of the key terms and philosophical approaches is important before proceeding with scenario development:

Predetermined elements – these are predictable elements that do not depend on a particular chain of events. They seem certain, no matter which scenario plays out, and broadly fall under four categories:

- Slow-changing phenomena (e.g.: temperature rise due to global warming)

- Constrained situations (e.g.: The U.S.’s dependence on oil)

- In the pipeline – things that have happened, but the consequences have yet to unfold (e.g.: population growth)

- Inevitable conclusions (e.g.: rising debt and its impact on taxes)

Critical uncertainties – these are events that are uncertain but closely related to predetermined events. For example – a government’s reaction to rising debt.

Errors can build in scenario planning when predetermined elements are mixed with critical uncertainties. Thus, a hallmark of scenario planning is separating what is predictable (predetermined) from what is truly open to change (uncertain).

Inductive versus deductive scenario construction – The inductive approach moves from specific ideas or factors to general laws, while the deductive approach begins with general overarching concepts and filters down towards specific ones.

Inductive scenario construction is often the simplest approach to scenario planning and is implemented using two strategies:

- Brainstorming: generating a variety of scenarios based on major events or innovations that have dramatic implications. This method requires the participants to be highly “tuned in” to their industry and organization.

- Official future: develop a picture of what the future might look like, usually with the help of a forecast, and then ask, “Where might the forecast be wrong?”

Deductive scenario construction works by bringing a cross-section of organizational decision-makers together to work on strategic issues and draw on collective thinking within the organization to tackle difficult problems and dilemmas.

Having established the important terms and approaches to scenario development, we now look at the eight important and well-known pieces of scenario development:

Brainstorming major forces (Workshop – 1)

The purpose of this workshop is to capture what participants perceive as major forces that the organization is facing concerning the problem or the issue defined. It works best when participants are given enough time and opportunity to speak.

It is important to welcome every perspective without judgment and establish ground rules to ensure everyone speaks – specifically when dominating personalities are present. The goal is to get the ideas flowing freely and include everything, no matter how far-fetched they may initially seem.

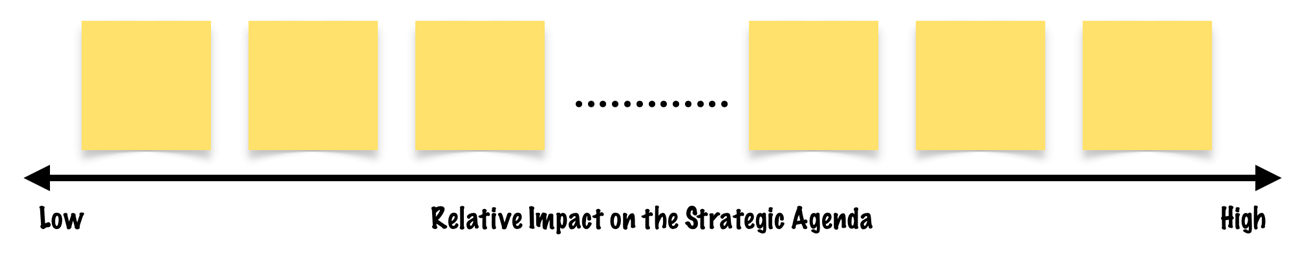

Ideas must be captured on sticky notes and posted on wall space or whiteboards for everyone to see. Order does not matter at this stage. An example layout is as shown:

Ranking forces by their relative impact on the organization (Workshop – 2)

Once the forces are identified, the next step is to rank them in order of their impact on the strategic agenda. This can be accomplished by arranging the sticky notes (recorded earlier) on a horizontal axis as shown:

The goal is to separate the truly critical factors from the others – the ones that have the power to fundamentally reshape the business. While viewpoints will differ, conversations

that develop around understanding varying viewpoints help build shared mental models.

Face-to-face dialogue in this step is critical to scenario planning. The knowledge friction – the resolution of multiple viewpoints into a more complete understanding is what drives a significant shift in insight.

Ranking forces by relative uncertainty (Workshop – 3)

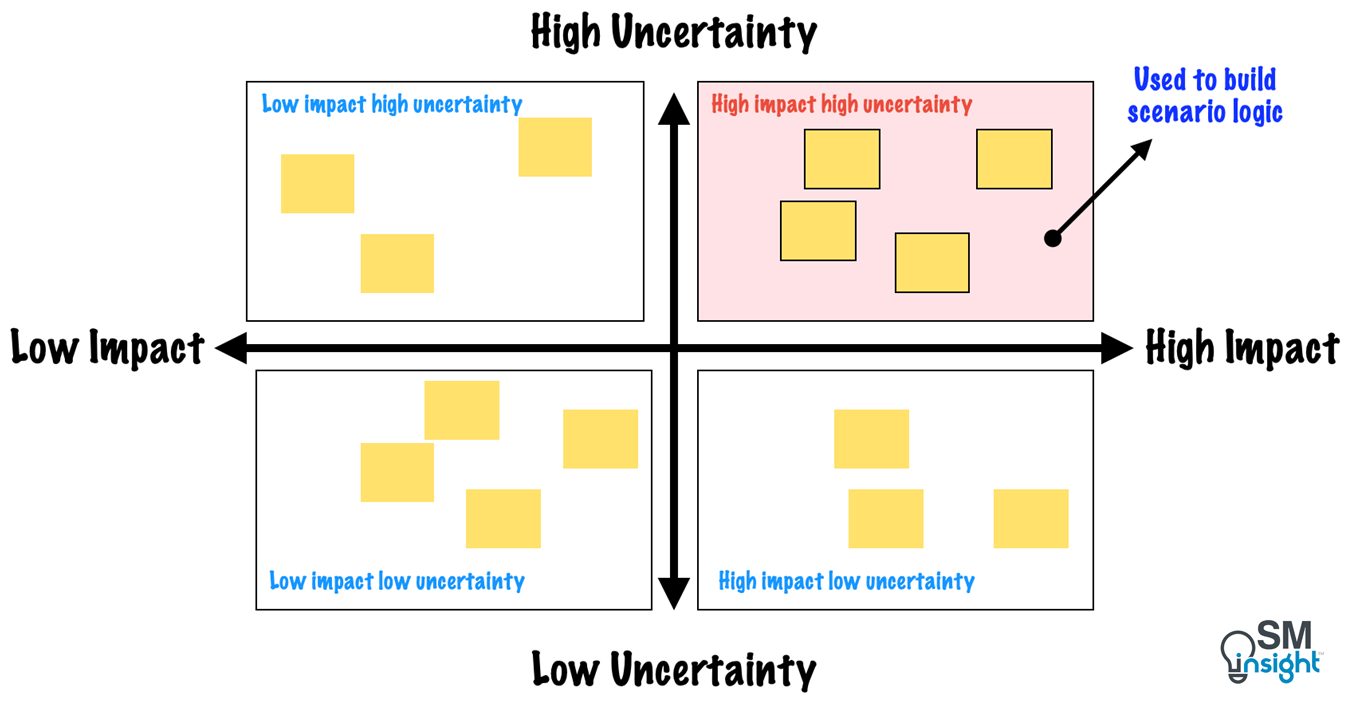

The next step is to rank the forces according to their uncertainty levels. A high uncertainty means that the eventual outcomes of these issues/forces remain unknown/unpredictable. Ranking can be achieved by vertically separating forces arranged earlier on a “Low” to “High” uncertainty scale as shown:

As in the previous stage, disagreements are expected. Conversation, debate, and dialogue are crucial to expand participant’s perceptions. By listening to a variety of perspectives and describing their own, participants build the initial mental scaffolding that is required to develop a shared mental model.

Building the scenario logic(s) (Workshop – 4)

Scenario logics are general frameworks or plots that are also known as proto-scenarios. Once the participants have ranked the forces by impact and uncertainty, the ranking space is divided roughly into quadrants:

These quadrants represent four general areas, each of which must be treated differently:

- High impact–Low uncertainty: these are major forces but with relatively stable and predictable outcomes. Major industry shifts already underway, such as government regulation changes, belong to this category.

- Low impact–Low uncertainty: these are forces that can be readily dealt with and generally do not require more analysis.

Forces in two of the above quadrants belong to the category of predetermined elements described earlier. It is important to ensure that they genuinely belong in this category. Uncertain elements if misread and grouped as predetermined elements can lead to significant errors in judgment.

- Low impact–High uncertainty: these are forces with high uncertainty ranking (eventual outcomes are unknown). Even though their impact is agreed to be low, it is worth conducting more research to verify their potential impact.

- High impact–High uncertainty: these are critical uncertainties with the potential to fundamentally shift the strategic agenda with highly uncertain outcomes. They are the ones used to construct scenario logic(s).

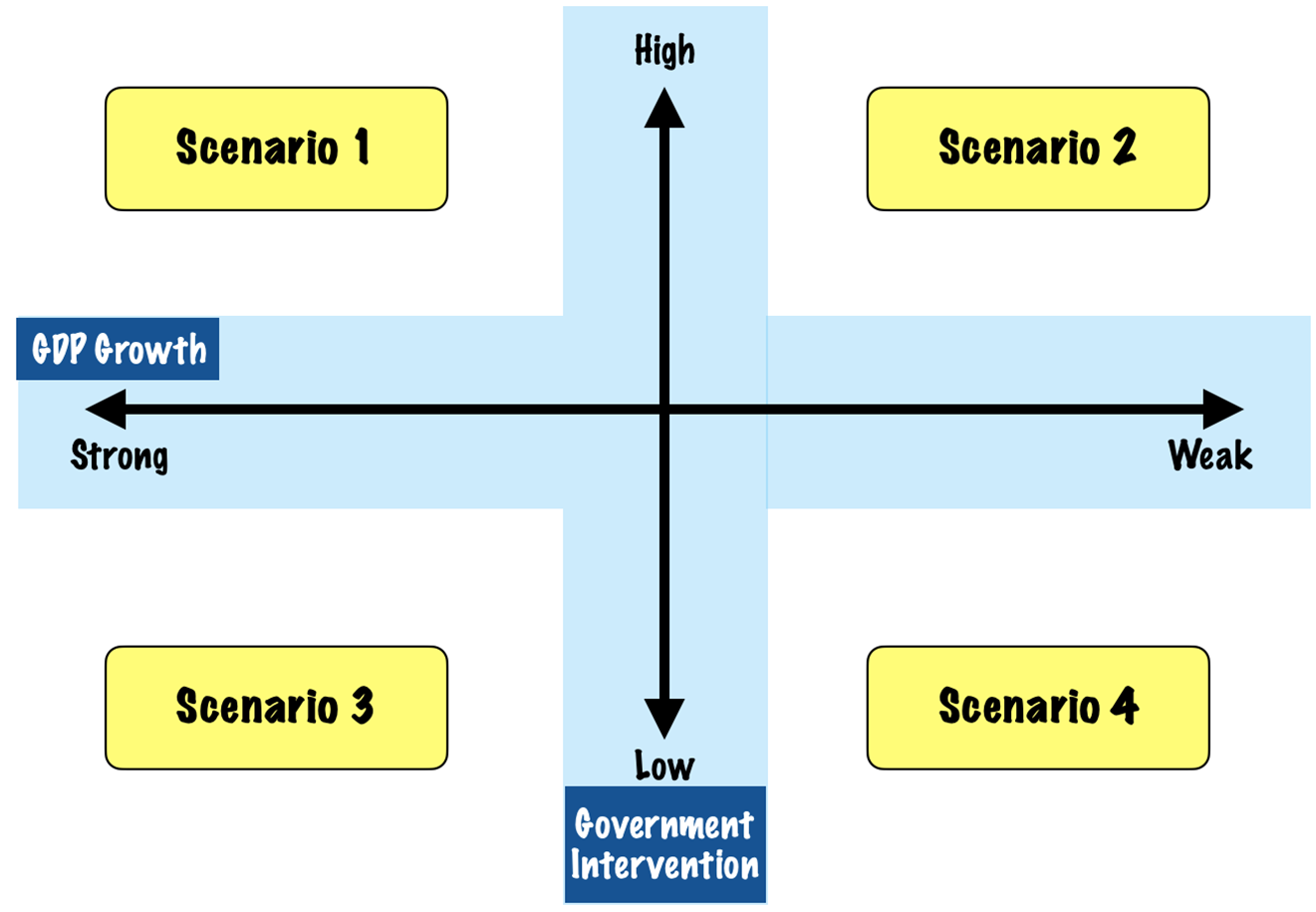

Developing scenario matrix: Once the high-impact, high-uncertainty forces are identified, two of the most critical ones are selected. Using normative judgment, a high and low value is assigned to each to construct a 2 x 2 matrix that gives rise to four scenarios:

The team can choose the two critical uncertainties using a variety of methods such as value voting [17], dot voting [18], and the nominal group technique [19]. It is also worthwhile to experiment with a few different 2 × 2 matrices to get a sense of the different scenario logic that can surface from this part of the workshop.

The emerging scenario logics must be plausible, challenging, and relevant.

In this context, challenging means they must assemble events and facts in a way that challenges the current mental models while relevance means they must relate to the key issues that have been expressed during the project and draw on real concerns of managers in the organization.

Generating scenario using the “Official Future”: Sometimes it is useful to include a “surprise free” status quo scenario, called the “official future” which is an extension of the past into the future and holds little challenge. This helps managers who have a difficult time adjusting to scenario thinking by allowing them to draw contrast with other more challenging scenarios and expand decision-making.

Constructing the research agenda

With the scenario logics in place, the next step is to write scenario stories for each of them. But first, further research must be conducted. Members (or sub-groups) of the team must work to gather more information on the driving forces in each scenario.

The research must accomplish three key goals in each scenario: Identify the driving forces, explain the uncertainties involved, and determine the inevitable factors.

Defining the plots and titles

It is helpful to have the general plot outlined and defined before the storyline is written. While there can be many themes to plot writing, the most common ones are:

- The “winners and losers”– this is a classic protagonist against an antagonist plot where only one character can “win.” therefore, the other must “lose.” (e.g.: a given firm vs its competition, either or technology bets)

- The “challenge and response” – a situation in which the actions of a group and related consequences become the basis for the story (e.g.: an economic crisis where a company must survive through times of layoffs, low growth, and declining stock value)

- The Evolution – involves slowly changing phenomena. Examples include tech innovations that start small with early adopters, and at some point, become mainstream. Being ahead of or behind the explosion can have dramatic implications.

Plots should also draw the key factors and trends from the interviews, brainstorming, and ranking exercises. When scenarios reflect the thinking and concerns of the managers, they are likely to be taken seriously. The goal is to develop plot lines that integrate dynamics and interestingly present them while summarizing the information effectively.

Likewise, titles are also important elements that provide an easy way to talk about the different worlds that may confront the organization and its decision-makers. It is a good practice to include an image along with the title when representing scenarios.

Writing scenario stories

A scenario story must be detailed and based on the key factors and trends identified in the previous workshops. While most activities till this stage were best suited to groups, scenario writing is best performed individually.

Some of the approaches to scenario writing include assigning each scenario to an individual; assigning to a pair of authors, one as the writer, and one as a veteran of the organization; assigning to an individual with access to an experienced scenario writer/editor; or assigning all scenario writing to one individual (usually a talented writer).

Best practices include:

- Structuring the story into three parts – beginning, middle, and end.

- Having elements that remain constant – not everything must change.

- Using characters and building tension between them as the story unfolds.

- Presenting dilemma(s), or providing twists.

- Including dramas and conflicts.

- Use present verb tenses (eg: “might haves” or “could haves”).

It is also important to involve decision-makers in the scenario-writing to ensure they own them.

Scenario communication

Having well-constructed scenarios sitting in a document won’t do much good. Once a set of scenarios believed to be high in quality and utility are finalized, they must be communicated throughout the organization using multiple methods including videos, websites, workbooks, role-playing activities, audiotapes/podcasts, presentations, and workshops.

The goal of communicating scenarios is to use them purposefully to examine the initial issue, test the business idea, and explore other aspects of the organization in each of the alternative futures.

Phase 4: Scenario implementation

Implementation is the first phase of the scenario deployment stage. General objectives are to provoke strategic insights, expand the assumptions of decision-makers, and develop the capacity to see major discontinuities before it’s too late. In addition to this, specific objectives that were defined during the project preparation drive this phase of the project.

Through a set of well-designed workshops, the developed scenarios are used to assess the organization in a variety of alternative futures. Strategies include using the scenarios to examine the initial question, testing the current theory of the business/business idea, analyzing current strategies, and developing strategic resilience and robustness.

While the toolbox to access scenarios is extensive, the most common ones include Lewin’s force field analysis [20], Nominal group technique [19], Team building, Value voting [17], Simulations and Visioning [21].

Scenarios are best implemented through a series of five workshops as detailed below:

Examining the initial question (Workshop – 1)

The first step in scenario implementation is to return to the initial purpose or the problem and develop different ways to explore answers. The workshop is best executed in an informal setup where the team along with the decision makers assemble for a brainstorming session.

Participants are given a short presentation of the scenarios developed, briefly covering their essence. The project leader then facilitates a dialogue related to the initial question. Some of the questions that help initiate the dialogue are:

- What are some of the learnings from the scenario development process that relate to the initial question?

- How does each scenario address the initial question?

- Are the answers different in each scenario?

- What additional information, if known, could be of value?

- In what ways do the developed scenarios solve the organization’s strategic dilemma?

- What are the clear strategic opportunities that can be seen in each scenario?

- Having considered each of the scenarios and their implications, what general actions could be recommended around the initial problem(s)/question(s)/issue(s)?

The goal of this workshop is to begin a genuine conversation about the potential issues decision-makers may face and to provide a mechanism to reflect on the future.

Scenario Immersion (Workshop – 2)

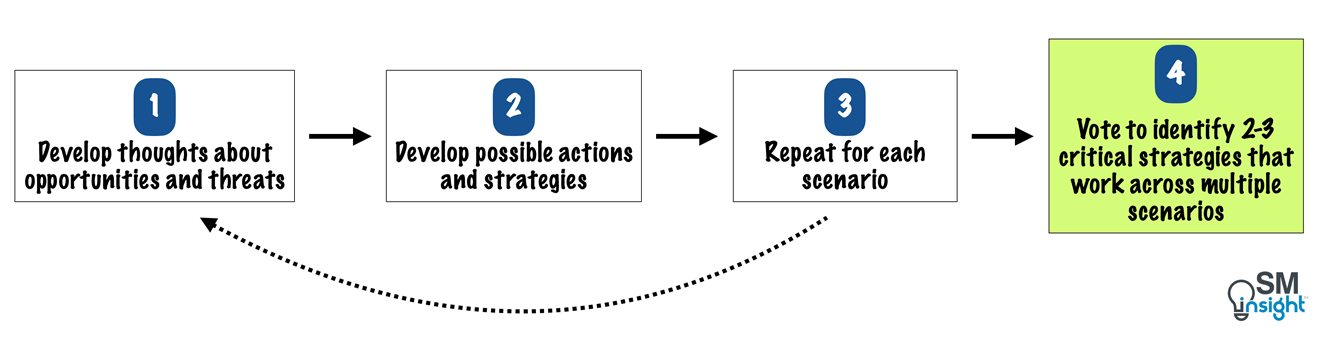

This step involves participants developing their thoughts about the opportunities and threats as well as possible actions and strategies in each scenario. The team looks for strategies that appear in more than one scenario and identifies two or three strategies that can be viable across all or multiple scenarios.

The idea is to leverage the collective capital of the participants in the room to distil two to three strategies that can work across multiple scenarios.

Test the theory of business (Workshop – 3)

The idea of this exercise is to examine if the organization’s theory of business holds good in

each scenario. The scenario team presents a scenario to decision-makers, and a dialogue is initiated about how (or if) the theory of the business may need to change to be viable.

Key questions for testing the theory of the business include:

- Do the organization’s assumptions about its environment, mission, and core competencies fit or enable it to act within each of the scenario futures?

- Do those assumptions fit with each other in each of those futures?

- Can the organization continue serving a business need with existing products/services in each of the future scenarios?

- Are the current distinctive competencies still valid in those futures?

- Could the organization lose its competitive advantage? if so, in what ways?

- Is the theory of the business known and understood throughout the organization?

- How can the organization continuously test its theory of the business?

Analyze current strategies (Workshop – 4)

Decision-makers always operate under a set of strategic goals. The idea of this workshop is to view them through the “lens” of each scenario to check if they make (or do not make) sense.

While this is an optional workshop, the key idea here is to identify a manageable set of strategies that contribute to the advancement of the organization. Goals and strategies that are found to distract from the core purpose (the theory of the business/business idea) can be potentially removed from the strategic agenda.

Develop Signals (Workshop – 5)

Signals are the events in a scenario which indicate that the story is beginning to unfold. Also referred to as “leading indicators” or “signposts”, they signal that a projected scenario is beginning to become a reality.

The team revisits each scenario and tries to identify events that could be triggers of larger change tendencies. The idea is to build the “anticipatory capacity” of the organization by defining what to look for in the future timeline (usually 6-18 months).

Create experiential learning (Workshop – 6)

These are workshops that attempt to bring the imagination into reality to increase learning.

One approach could be to have scenario-themed rooms (usually four), with each reflecting different scenarios. Walls can be plastered with artefacts, posters, banners, and articles that characterize the scenarios. Cross-organizational teams can then be assigned to each room where they present the scenario and explain how the story may unfold.

Research has shown that such attempts help bring imagination into reality and increase learning. This is also why the military has used simulations and virtual reality technologies for decades.

A second benefit of this exercise is that it leverages what is known as “suspension of disbelief” [22]. Since most scenarios are invariably met with disbelief, a well-constructed narrative helps people “park” their “critical thinking” for a few moments and become receptive to the other side of possibilities.

Experiential learning workshops such as these require a great deal of time and effort to design, but their payoffs are well worth the effort.

Building resilience and robustness

Decision makers can use the scenarios to examine their strategy, goals, human resource capacity, specific decisions and outcomes, business models, and a variety of other items.

Additional or substitute workshops can be designed around these organizational elements. The workshops need only to inform the initial purpose of the project. Beyond that, the scenarios should be used to explore. The more creatively they are used, the further the thinking inside the organization can potentially be shifted.

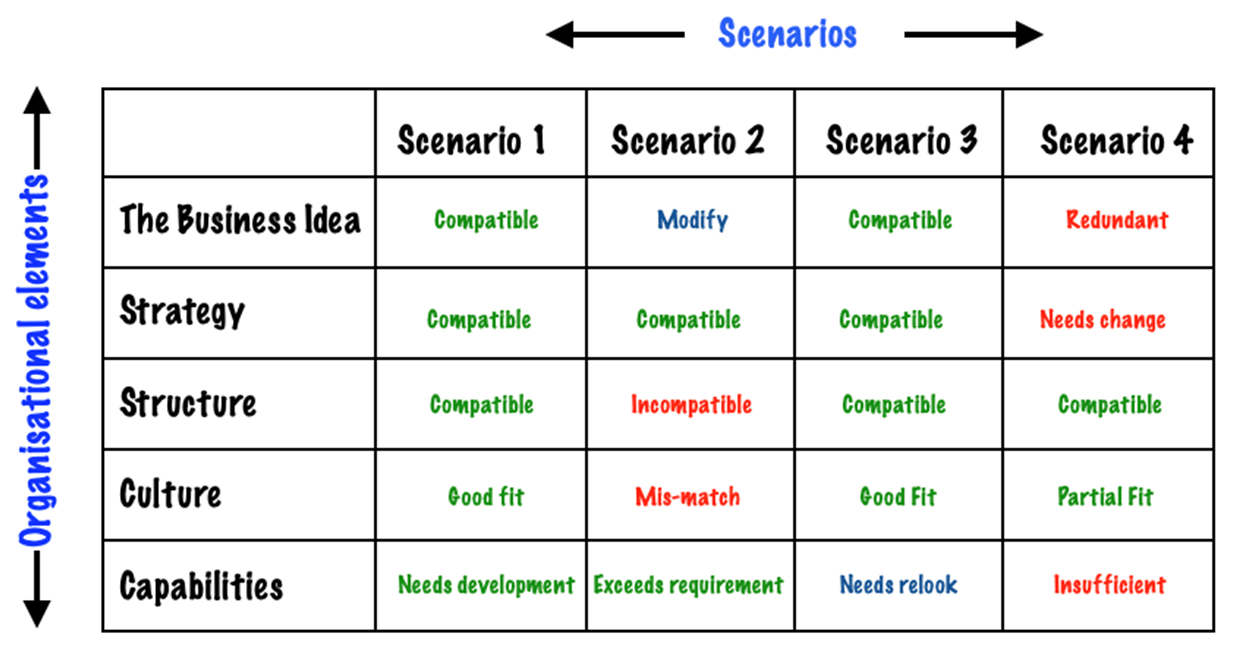

The below figure shows a basic structure for testing various organizational elements through each scenario:

In all, there is a lot of freedom in finding the most useful ways to implement and apply scenarios. The workshops discussed thus far demonstrate the use of testing various organizational elements to ensure the development of resilient and robust strategies.

Phase 5 – Project Assessment

Scenario projects, by their very nature, deal with the world of perceptions. Most change efforts are assessed based on whether participants perceived the project to be useful and enjoyable, which, unfortunately, is not a wholesome measure of success.

Performance measures in scenario planning projects can, at best, be estimates as the very purpose of such projects is either to avoid regret or to generate insights that were previously beyond the mind’s reach.

A responsible assessment effort must include three domains: satisfaction; learning and performance:

Measuring satisfaction

To measure satisfaction, participants and stakeholders are asked to respond to a short survey that assesses their opinions about the utility of the change intervention brought in by the scenario planning exercise.

Participant perceptions can provide valuable information for making subtle adjustments to any change project. However, they must not become the primary measure of success. It is also important that the project meets other stakeholder expectations.

Measuring learning

To drive change is also one of the important goals of the scenario planning exercise. However, people cannot change their behaviors unless they have strategic insights or have discovered novel ways of seeing situations differently.

Learning, as a consequence of a scenario project, can be in the form of both knowledge and expertise. Hence, it is important to assess what it is that participants know and can do differently because of their engagement in the scenario project.

Measuring performance

Given the timeline of events, measuring performance is the most difficult part of assessing a scenario project. In general, performance results in two areas – system and financial.

System results refer to the increased or maximized output in terms of product, good, or service achieved through the change intervention, while financial results refer to monetary gains resulting from those improvements.

Organizations often limit their focus to satisfaction surveys, but effective performance improvement initiatives go beyond that. It is crucial to apply these principles to gain a comprehensive understanding and document the impact of scenario projects.

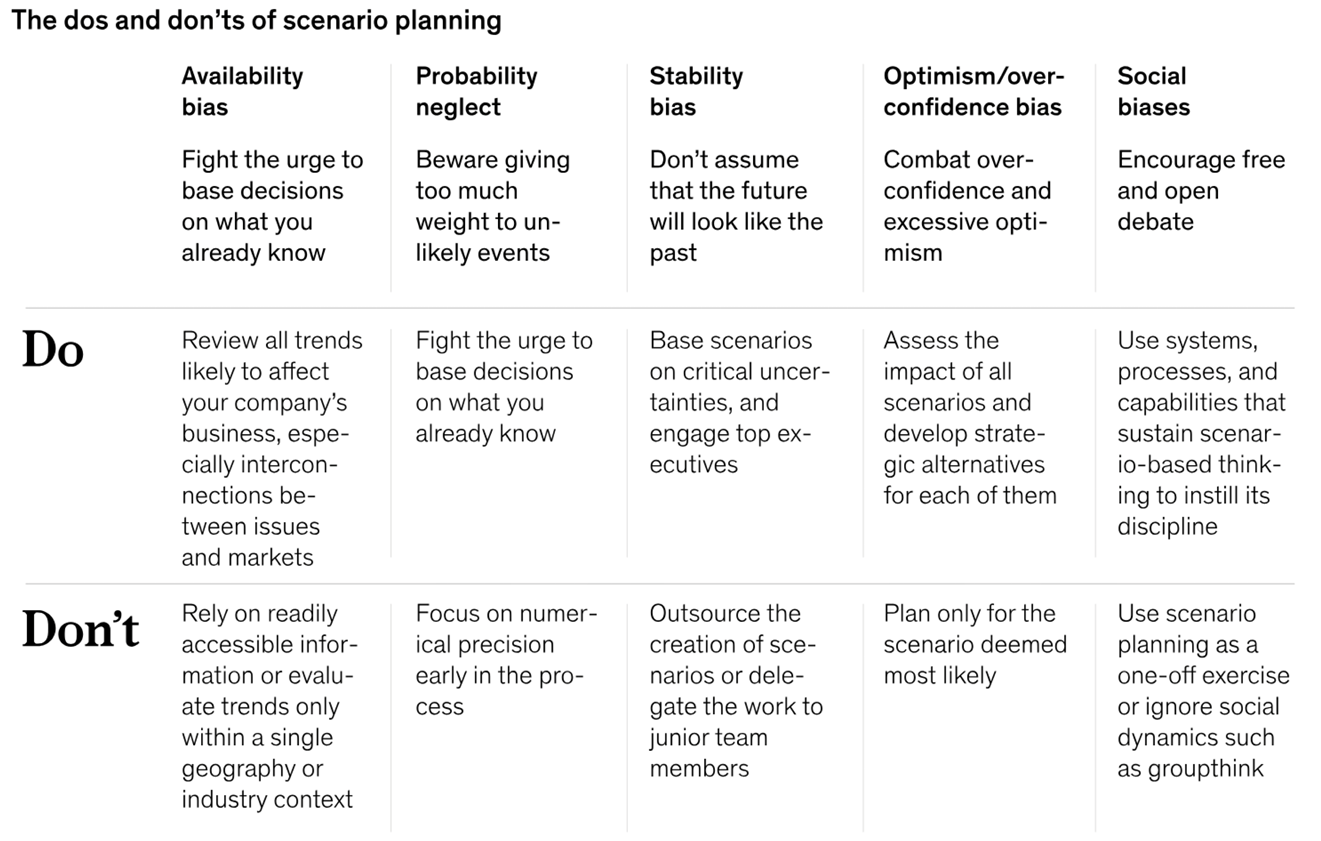

Avoiding bias that undermines scenario planning

While scenario planning has worked well and proved to be enormously useful to a wide range of organizations, it has also been a disappointment to many. In a survey conducted in 2013, 40% of the respondents described it as having little effectiveness.

A McKinsey report [23] argues that scenario planning can be hampered by the same deep-seated cognitive biases that it should be used to address. Fortunately, understanding how such biases undermine scenario planning can help improve their effectiveness:

To embed scenario thinking, organizations must institutionalize new mental habits and ways of working. Leaders must simultaneously instil a conviction that change is needed throughout the organization, role model the desired new behavior, reinforce processes and systems to counter bias and ensure that the company acquires or builds the skills needed to support the approach.

Sources

1. “Scenarios: learning and acting from the future”. Paulo Soeiro de Carvalho, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351904805. Accessed 08 Aug 2024.

2. “Herman Kahn”. Hudson.org, https://www.hudson.org/experts/174-herman-kahn. Accessed 08 Aug 2024.

3. “Scenario planning”. Stanford Research Institute, https://www.sri.com/hoi/scenario-planning/. Accessed 04 Aug 2024.

4. “Oil Embargo, 1973–1974”. Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute, U.S., https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/oil-embargo. Accessed 04 Aug 2024.

5. “Learning from the Future”. Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2020/07/learning-from-the-future. Accessed 04 Aug 2024.

6. “Scenario planning”. The Economist, https://www.economist.com/news/2008/09/01/scenario-planning. Accessed 04 Aug 2024.

7. “Scenario Analysis and Contingency Planning”. Bain & Company, https://www.bain.com/insights/management-tools-scenario-and-contingency-planning/#. Accessed 04 Aug 2024.

8. “The use and abuse of scenarios”. McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-use-and-abuse-of-scenarios. Accessed 04 Aug 2024.

9. “Scenario planning and war-gaming: Sizing up the future”. Deloitte, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/risk/us-reimagining-rie-eminence-series.pdf. Accessed 04 Aug 2024.

10. “Lessons From the Catastrophic Failure of the Metaverse”. The Nation, https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/metaverse-zuckerberg-pr-hype/. Accessed 05 Aug 2024.

11. “Scenario Planning in Organizations: How to Create, Use, and Assess Scenarios”. Thomas J. Chermack, https://www.amazon.com/Scenario-Planning-Organizations-Create-Scenarios/dp/1605094137. Accessed 06 Aug 2024.

12. “Deloitte Acquires Monitor Group (and thus, GBN)”. Strategic Innovation Lab, https://slab.ocadu.ca/story/deloitte-acquires-monitor-group-and-thus-gbn. Accessed 07 Aug 2024.

13. “PEST & PESTEL Analysis”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/pest-pestel-analysis/. Accessed 07 Aug 2024.

14. “Six Thinking Hats”. The De Bono Group, https://www.debonogroup.com/services/core-programs/six-thinking-hats/. Accessed 07 Aug 2024.

15. “SWOT Analysis – How to Do It Properly”. Strategic Management Insight, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/swot-analysis-how-to-do-it/. Accessed 10 Aug 2024.

16. “The Theory of the Business”. Peter F. Drucker (HBR), https://hbr.org/1994/09/the-theory-of-the-business. Accessed 08 Aug 2024.

17. “Quadratic voting”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quadratic_voting. Accessed 08 Aug 2024.

18. “Dot Voting”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dot-voting. Accessed 08 Aug 2024.

19. “WHAT IS NOMINAL GROUP TECHNIQUE?”. American Society for Quality, https://asq.org/quality-resources/nominal-group-technique. Accessed 08 Aug 2024.

20. “Lewin’s Force field Analysis”. University of Cambridge, https://www.ifm.eng.cam.ac.uk/research/dstools/force-field-analysis/. Accessed 08 Aug 2024.

21. “How to Conduct a”. THE GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH CENTER, https://www.gdrc.org/ngo/vision-dev.html. Accessed 08 Aug 2024.

22. “Suspension of disbelief”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suspension_of_disbelief. Accessed 10 Aug 2024.

23. “Overcoming obstacles to effective scenario planning”. McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/overcoming-obstacles-to-effective-scenario-planning. Accessed 11 Aug 2024.