Setting goals is undoubtedly beneficial for individuals, teams, and organizations. Numerous studies show that goal setting positively impacts productivity and performance [1]. However, not everyone, and not every organization, can stick to goals or drive positive results.

A study of 800 million data points on the fitness platform Strava showed that only 20% of New Year’s resolutions survive beyond the second week of February [2].

What, then, is the secret to a great goal that brings results? How do you set one, and what characteristics make it effective? To answer these questions, we look at Goal-setting theory, a theory of motivation that explains what causes some people to perform better on work-related tasks than others.

Professors Edwin A. Locke [3] and Gary P. Latham [4], two of the most well-known academic researchers on goal-setting theory, have contributed immensely to this field. Based on 35 years of empirical research, they have described their core findings and demonstrated the mechanisms by which goals operate [5].

In this article, we look at the mechanisms by which goals drive performance and the underlying moderators that make some goals more effective than others.

How Goals Affect Performance

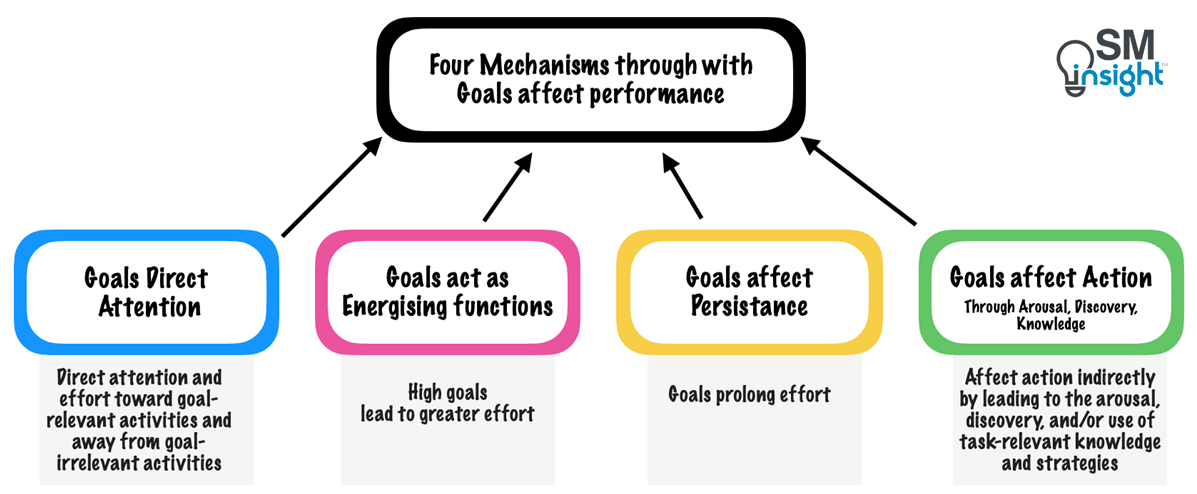

Goals affect performance through four mechanisms:

- Goals serve as a directive function: they direct attention and effort toward goal-relevant activities and away from goal-irrelevant activities. This effect occurs both cognitively and behaviorally.

For example, a study found that students with specific learning goals were more attentive to and learned goal-relevant prose passages better than goal-irrelevant passages [6]. Likewise, when people were given feedback about multiple aspects of their driving performance, they showed improvement on the dimensions for which they had goals but not on other dimensions [7]. - Goals have an energizing function: High goals lead to greater effort than low goals. This applies to all kinds of tasks, including those that entail physical effort, repeated performance, subjective effort, and physiological effort.

- Goals affect persistence: Hard goals prolong effort. While there is a trade-off in work between time and intensity of effort, when faced with a difficult goal, it is possible to work faster and more intensely for a short period or to work more slowly and less intensely for a long period. Tight deadlines also lead to a more rapid work pace.

- Goals affect action: Theyindirectly lead to arousal, discovery, and/or promote the use of task-relevant knowledge and strategies. Research indicates that when people face task goals, they instinctively utilize their existing relevant knowledge and skills.

If achieving the goal requires more than a set of automatized skills, people draw from their repertoire of previously used skills in related contexts and apply them to the current situation. With the right set of goals, people will also engage in deliberate planning to develop strategies to attain them.

Key Findings By Locke and Latham

The core premise of goal-setting theory is that goals are immediate, if not the only, regulators of human action. With this, Locke and Latham studied and uncovered several findings related to goal setting:

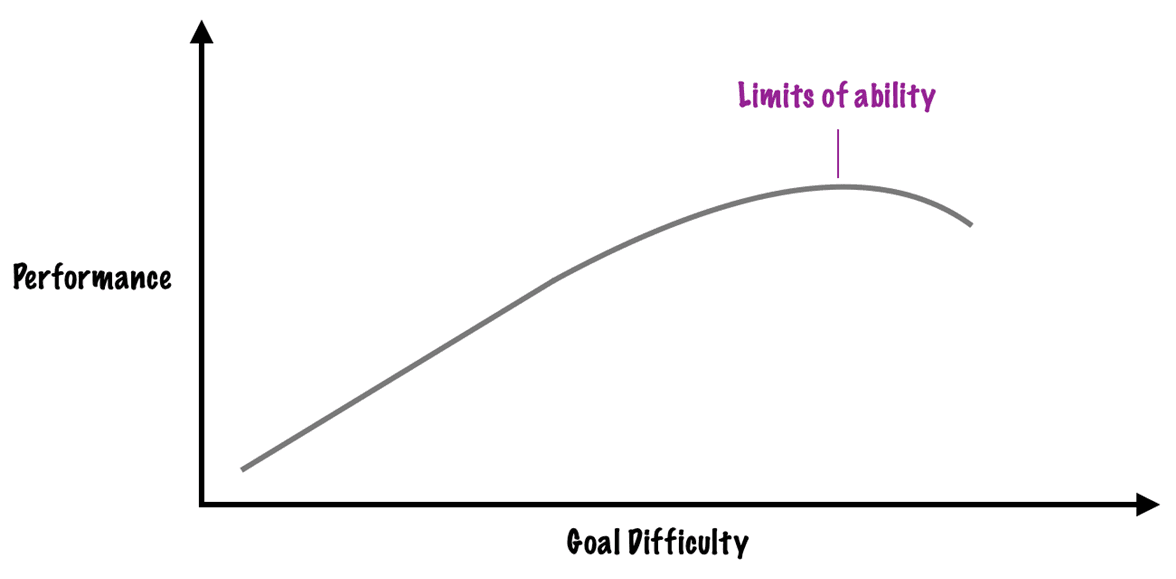

There is a linear relation between goal difficulty and performance

There is a linear relationship between the degree of goal difficulty and performance, except when subjects reach the limits of their ability. Performance levels drop as the goal reaches difficulty levels beyond one’s ability.

Locke found that the performance of participants with difficult goals was over 250% higher than those with the easiest goals.

Specific, difficult goals lead to higher performance than vague, “do best” goals.

Specific and difficult goals lead to a higher level of performance than vague, nonquantitative goals such as “do your best,” “work at a moderate pace,” or no assigned goals. While “do your best” goals, despite being nonquantitative, imply a high level of motivation, they remain ambiguous about what constitutes performance effectiveness.

A specific, high goal eliminates ambiguity. It defines what constitutes an acceptable level of performance for an individual (or a team), bringing clarity and focus.

Ability limits goal achievement and performance.

In goal-setting theory, ability is a moderator variable that affects the relationship between goal and performance. Ability affects the choice of goal because people cannot perform when they lack the knowledge and skill to obtain that level of performance.

Locke found that within the limits of ability, goal difficulty level and performance were strongly correlated ( 0.82 ( p < 0.001) ). However, once impossible goals were set, the correlation dropped to 0.11.

Goal setting has also been shown to have a greater positive effect on the performance of people and teams with high ability compared to those with lower ability.

Goal commitment plays a crucial role.

The goal-performance relationship is strongest when people are committed to their goals.

This is particularly important for difficult goals, which require high effort and are associated with lower chances of success than easy goals. Locke and Latham identified two categories of factors that facilitate goal commitment:

Importance

Factors that make goal attainment important, including the importance of the outcomes expected as a result of working to attain a goal.

There are several ways to convince people that goal attainment is important. Making a public commitment to the goal enhances commitment because it makes one’s actions a matter of integrity in one’s own eyes and in those of others.

Goal commitment can also be enhanced by leaders communicating an inspiring vision and behaving supportively. A supervisor’s legitimate authority to assign goals also creates demand characteristics [9].

Alternatively, when subordinates are allowed to set goals, it helps increase their importance because one would, at least in part, own such goals. However, a series of studies by Latham and his colleagues revealed that when goal difficulty is held constant, the performances of those with participative set versus assigned goals do not differ significantly.

Another factor affecting goal commitment is peer influence, specifically peer pressure and modeling. Strong group norms are known to produce commitment in the form of low variance among group members. Commitment to high goals occurs when the group norms are high and when peers perform at high levels.

Monetary incentives and rewards are another practical outcome that can be used to enhance goal commitment. More money generally leads to more commitment. However, when the goal is very difficult, paying people only if they reach it can hurt performance.

Once people see that they are not getting the reward, their personal goal and their self-efficacy drop, and consequently, so does their performance. This drop does not occur if the goal is moderately difficult or if people are given a difficult goal and are paid for performance rather than goal attainment.

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is the belief that the goal can be attained. It enhances goal commitment. Leaders can raise the self-efficacy of their subordinates by:

- Ensuring adequate training to increase mastery that provides successful experiences.

- Role modeling or finding models with whom the person can identify.

- Using persuasive communication to express confidence that the person can attain the goal. This could also involve giving subordinates information about strategies that facilitate goal attainment.

Without feedback, goals are ineffective.

For goals to be effective, people need feedback that reveals progress against the goals. Without this, it is difficult or impossible to adjust the level or direction of effort or performance strategies to match what the goal requires.

Feedback plays two roles in goal setting: First, it stimulates performers to set goals for themselves, and those feedback-based goals subsequently help them improve their performance. Second, it tells them how well they are doing in relation to those goals, thereby strengthening the impact of goals on performance.

Goals and feedback together lead to higher performance than either one alone. This is because goals direct and energize action, while feedback allows tracking progress in relation to the goal. When people are below target, they normally increase their effort or try a new strategy.

Setting performance goals can be detrimental when the task is complex; use learning goals instead.

Task complexity can be defined in terms of three dimensions: component complexity, which is the number of elements in the task; coordinative complexity, which is the number and nature of the relationships between the elements; and dynamic complexity, the number and types of elements and the relationships between them over time.

As the complexity of the task increases, higher-level skills and strategies are required to achieve performance. In such cases, goal effects depend more on the ability to discover appropriate task strategies. Because people vary greatly in their ability to do this, the effect size for goal setting is smaller on complex than on simple tasks.

For example, one study found that in an air traffic controller simulation (a highly complex task), having a performance goal interfered with acquiring the knowledge necessary to perform the task. Performance improved when people were asked to do their best. However, setting a specific difficult learning goal (rather than a performance goal) led to significantly higher performance, consistent with the goal-setting theory [5].

Performance goals work by influencing the choice, effort, and persistence needed to attain them. While performance is a function of motivation, it also depends on ability, especially when the task is complex. Setting a specific performance goal is ineffective in such situations. What’s required is learning rather than increased motivation. Hence, a specific high-learning goal should be set.

For example, a novice golfer should consider setting a high learning goal, such as learning how to hold a club or when to use a specific iron. In short, novice golfers must learn how to play the game before attempting to attain a challenging performance outcome (say, a score of 95).

In one study [10], researchers used the Cellular Industry Business Game (CIBG), a complex simulation based on the U.S. cellular telephone industry, to test the impact of learning versus performance outcome goals. Participants had to make strategic decisions across 13 rounds, covering areas such as pricing, advertising, and finance, involving deregulation, changing market conditions, etc.

Here are the key findings:

- Participants with specific high-learning goals achieved nearly double the market share compared to those with performance goals or no specific goals.

- Individuals with a learning goal took the time necessary to acquire the knowledge to perform the task effectively and analyze the task-relevant information available to them.

- Learning goals boosted self-efficacy through the discovery of effective strategies (performance goals, in contrast, led to erratic problem-solving).

Those with a learning goal were more committed to their goal than those with a performance goal. The correlation between goal commitment and performance was also significant.

Five principles (key takeaways) from Locke & Latham’s goal-setting theory

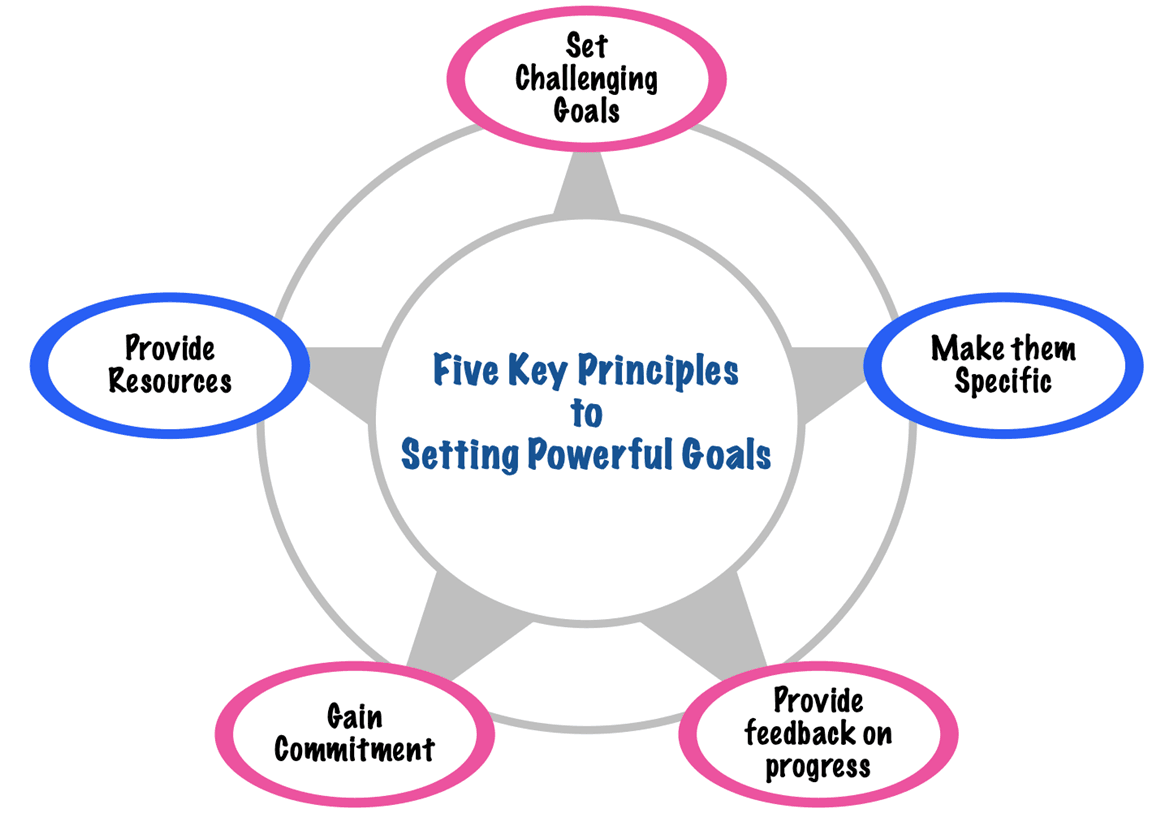

1. Set challenging goals

In addition to being targets to attain, goals are the standards by which one judges one’s adequacy or success. Challenging goals facilitate pride in accomplishment.

People with low goals are minimally satisfied with low-performance attainment and become increasingly satisfied with every level of attainment that exceeds their goal. This is also true for individuals with a high goal. To be minimally satisfied, they must accomplish more than those with low goals. Consequently, they set a high goal to attain before they are satisfied with their accomplishment.

In short, to be satisfied, employees with high standards must accomplish more. Outcome expectancies are typically higher for attaining high rather than low goals because the outcome one can expect from attaining a challenging goal usually includes such factors as an increase in feelings of self-efficacy, recognition from peers, a salary increase, a job promotion, etc. As a result, people, in most instances, commit to high goals.

2. Make goals specific

Goal specificity facilitates an employee’s focus. It makes explicit what the individual has chosen to exert effort into persistently. Specificity also facilitates measurement and feedback on progress toward goal attainment.

In contrast, an abstract goal such as “do your best” allows people to give themselves the benefit of the doubt concerning the adequacy of their performance. They fail to arouse maximum effort.

For feedback to be used intelligently, it must be interpreted in relation to a specific goal. Goal specificity clarifies what constitutes effective performance for the employee. It helps align the goal with the measurement of progress.

Challenging, specific goals affect persistence. Studies have shown that when no time limits are imposed, specific high goals induce people to work faster or harder than when low or abstract goals are set.

When to set learning goals

Learning goals have proven more beneficial for complex tasks or tasks that are beyond one’s current abilities. They have also proven particularly helpful in improving performance in at least three areas: leadership, performance management, and professional development [10].

- Leadership: Having a leader focus employees’ attention on attaining learning goals has proven beneficial for several firms. Jack Welch at GE, Andy Grove at Intel, and Sam Walton at Walmart have all developed such a culture [10]. They were obsessed with learning about the changing environment and never stopped learning from competitors, customers, and their own employees.

All three companies saw an increase in the effectiveness of their workforce by setting specific high-learning goals for sharing ideas among divisions, identifying potential threats in the environment, or extracting ideas from competitors, customers, and employees.

People’s leadership skills are developed by assigning specific learning goals that require them to go outside their comfort zone. - Performance management: Many companies incorporate goal setting into their coaching and mentoring practices. These are typically performance or behavioral goals that fall within the limits of the employee’s knowledge and abilities.

Including learning goals in performance management processes can significantly improve results. Studies show that employees assigned challenging learning goals in the early stages of their jobs typically outperform those initially given specific high-performance targets.

PWC, for example, sets learning goals and hires job applicants based on their aptitude rather than existing skills [10]. New employees benefit from mentors who actively help them discover ways to develop competencies within the firm by assigning specific, high-learning, rather than performance, goals. - Professional development: To ensure ongoing professional development, firms subject their senior executives to job rotation. This allows them to learn new perspectives, get them out of their comfort zones, and develop greater creativity.

To ensure this occurs, specific learning goals should be set to ensure that the broad perspective to which the executives are exposed actually helps the company make decisions cohesively.

3. Provide feedback in relation to goals

As the popular saying goes, “What gets measured gets done.” This means measuring something gives the information needed to achieve what one sets out to do. Goal theory improves the accuracy of this statement by inserting the word goal: “that which is measured in relation to goals is done.”

Both goal-setting theory and empirical research indicate that without goal-setting, feedback has no effect on performance. This is because feedback is only information. Its effect on action depends on how it is appraised and what decisions are made with respect to it.

Feedback is a relational concept that allows people to discern what they should continue doing, stop doing, or start doing to attain the goal. Immediate and detailed feedback is important in keeping us on track with our progress towards our goals.

4. Gain goal commitment

Goal commitment can be secured in two steps. The first is to focus on outcome expectancies. The leader’s role here is of a coach, helping people see the relationship between what they do and the outcome of their actions.

The focus must be on improving performance rather than on blame. This is done by increasing the team’s sense of control and helping people realize the outcomes they can expect by engaging in specific actions.

A second step to maintaining goal commitment is to increase the person’s self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a strong belief or a conviction that “I can make this happen.” Research has shown that it is not just our ability that holds us back or propels us forward but also our perception of our ability [11].

People with low self-efficacy look for tangible evidence to abandon a goal and look for confirmation that it is useless to persist in goal attainment. Conversely, people with high self-efficacy commit to high goals, view obstacles and setbacks as challenges to overcome, as sources of excitement to be savored.

The following three ways can be used to induce high self-efficacy:

- Enactive mastery: this involves sequencing a task in such a way that it guarantees early success. For example, to increase confidence in using a laptop, the following steps should be followed: Open/Close à On-Off à Keyboard Skills.

Early successes through “small wins” build confidence that “I can do this,” and the goal seems attainable. - Modeling: The idea here is to connect the goal-setter with individuals they can genuinely relate to—those who have recently mastered the task or are currently working through it. This instills an “if they can do it, so can we” attitude.

Model individuals should be relatable, as too large a gap between them and the goal-setter might lead to admiration but also feelings of discouragement. If the goal-setter perceives the gap as too wide, they may feel that the achievement is beyond their own capabilities, making it difficult to model the success they’ve witnessed. - Persuasion from a significant other: People tend to behave according to the expectations of those who are significant to them. Thus, a coach’s role is to determine the identity of the person’s significant other and have them communicate why they believe the person can attain the goal.

5. Provide resources needed to attain the goal

Goals are unlikely to be attained if situational constraints blocking their attainment are not removed. Organizations must ensure the time, money, people, and equipment necessary for goal attainment exist. Most importantly, the measurement system must not only allow accurate tracking of goal progress but must also be aligned to support the goal attainment.

Organizations must provide the required training to give people the knowledge and skills to attain the goal. This is because the relation of goal difficulty to performance is curvilinear. Performance levels drop off after the limit of ability has been reached.

Why organizations fail to follow Locke & Latham’s advice

In a nutshell, Locke and Latham’s research tells us to set specific, challenging goals with tight deadlines. Whether the goals are set collaboratively or handed down by a manager matters less as long as they are clearly defined and shared publicly.

The outcome: increased effort, greater persistence, and improved performance.

Yet, many organizations don’t follow this advice. Author Dick Grote identifies three popular goal-setting techniques in today’s organizations that go directly against these findings [12]: SMART goals, cascading goals, and using percentage weights to indicate relative goal importance.

Limitations of SMART goals

SMART is an acronym that states goals must be Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Time-bound. Many wording variations exist, but the essence is always the same. SMART goals have the following drawbacks:

- It does not help determine whether the goal itself is a good idea. In other words, a goal can easily be SMART without being wise.

- It encourages people to set low goals. People naturally aim for what seems achievable, but weak performers may use “Attainable” and “Realistic” as an excuse to set easy goals. This goes against setting challenging goals that drive the most effort and performance.

To overcome these dangers, organizations must avoid using SMART to determine which goals are wise or worth pursuing. Instead, they must use it only as a test to check whether goals are well stated.

Limitations of cascading goals

In most organizations, goals frequently cascade down from the top. It usually starts with the president or the CEO and moves down until finally, those at the bottom of the organizational food chain set their goals. This has the following drawbacks:

- If the concept of cascading goals is applied too rigidly, nobody can begin the goal-setting process until that person’s boss has finished their goals. The process drags, and everybody blames those one step above for slowing it down.

- A cascading goal-setting process also risks omitting important goals specific to an individual’s job that doesn’t have an obvious link to a superior’s goal.

To overcome these limitations, the goal-setting process must be free from any rigid requirement that individual goals must be tightly linked to the supervisor’s goals and limited only to the areas where the supervisor or the executive team has set their goals.

The goals set by one’s immediate supervisor represent an important data source about where a person might logically set her own goals for her job. However, they should never limit an individual’s goal-setting.

Limitations of using percentage weights

Some goals are certainly more important than others, but assigning percentage weights to them to indicate relative importance is counterproductive. This is because it is impossible to accurately identify the relative importance of goals at a good level of granularity (for example, should a goal be given 20% weight or 25%? That’s hard to say).

This also leads to a problem where goals are appraised at the end of the term as if they were arithmetic problems. Appraisers are tempted (or even instructed) to multiply the percentage weight of the goal by the numerical score they’ve assigned (say, on a 1-5 scale) to that goal and thus determine the assessment rating.

This reduces the performance appraisal, which should be a matter of good managerial judgment, to a matter of mathematical computation.

A better way to categorize goals is to put them into baskets such as High, Medium, and Low or list them in the approximate order of importance to indicate each goal’s relative degree of significance compared with the others.

Sources

1. “The Impact of Goal-setting on Worker Performance – Empirical Evidence from a Real-effort Production Experiment”. Sven Asmus, Florian Karl, Alwine Mohnen and Gunther Reinhart, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212827115001626. Accessed 05 Mar 2025.

2. “A Study of 800 Million Activities Predicts Most New Year’s Resolutions Will Be Abandoned on January 19: How to Create New Habits That Actually Stick”. Inc, https://www.inc.com/jeff-haden/a-study-of-800-million-activities-predicts-most-new-years-resolutions-will-be-abandoned-on-january-19-how-you-cancreate-new-habits-that-actually-stick.html. Accessed 05 Mar 2025.

3. “Introduction to Edwin A. Locke”. Edwinlocke.com, https://edwinlocke.com/. Accessed 07 Mar 2025.

4. “BIO: Gary Latham”. University of Toronto, https://discover.research.utoronto.ca/11453-gary-latham. Accessed 07 Mar 2025.

5. “Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation”. Edwin A. Locke and Gary P. Latham, https://www-2.rotman.utoronto.ca/facbios/file/09%20-%20Locke%20&%20Latham%202002%20AP.pdf. Accessed 05 Mar 2025.

6. “Goal-guided learning from text: inferring a descriptive processing model from inspection times and eye movements”. E Z Rothkopf and M J Billington, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/521546/. Accessed 06 Mar 2025.

7. “The directing function of goals in task performance”. Edwin A. Locke and Judith F. Bryan, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0030507369900300. Accessed 06 Mar 2025.

8. “A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance”. Edwin A. Locke, Gary P. Latham, Ken J. Smith, Robert E. Wood, Albert Bandura, https://www.amazon.com/Theory-Goal-Setting-Task-Performance/dp/0139131388. Accessed 07 Mar 2025.

9. “Demand characteristics”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demand_characteristics. Accessed 07 Mar 2025.

10. “LEARNING GOALS OR PERFORMANCE GOALS: IS IT THE JOURNEY OR THE DESTINATION?”. Gary P. Latham, Gerard Seijts and Gerard Seijts, https://iveybusinessjournal.com/publication/learning-goals-or-performance-goals-is-it-the-journey-or-the-destination/. Accessed 07 Mar 2025.

11. “Self-efficacy: The exercise of control”. Albert Bandura, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-08589-000. Accessed 09 Mar 2025.

12. “3 Popular Goal-Setting Techniques Managers Should Avoid”. Dick Grote (HBR), https://hbr.org/2017/01/3-popular-goal-setting-techniques-managers-should-avoid. Accessed 10 Mar 2025.

13. “The Blackwell Handbook of Principles of Organizational Behaviour”. Edwin A Locke, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781405164047. Accessed 10 Mar 2025.