Persuasion has been the subject of philosophical and academic inquiry since at least the time of Aristotle, but the scientific study of persuasion did not begin until the early post-World War II period.[1]

Early research in this area was guided by the notion that persuasion depended upon factors influencing people’s ability to successfully learn the information contained in persuasive communication but published studies conflicted with one another and failed to provide conclusive proof.

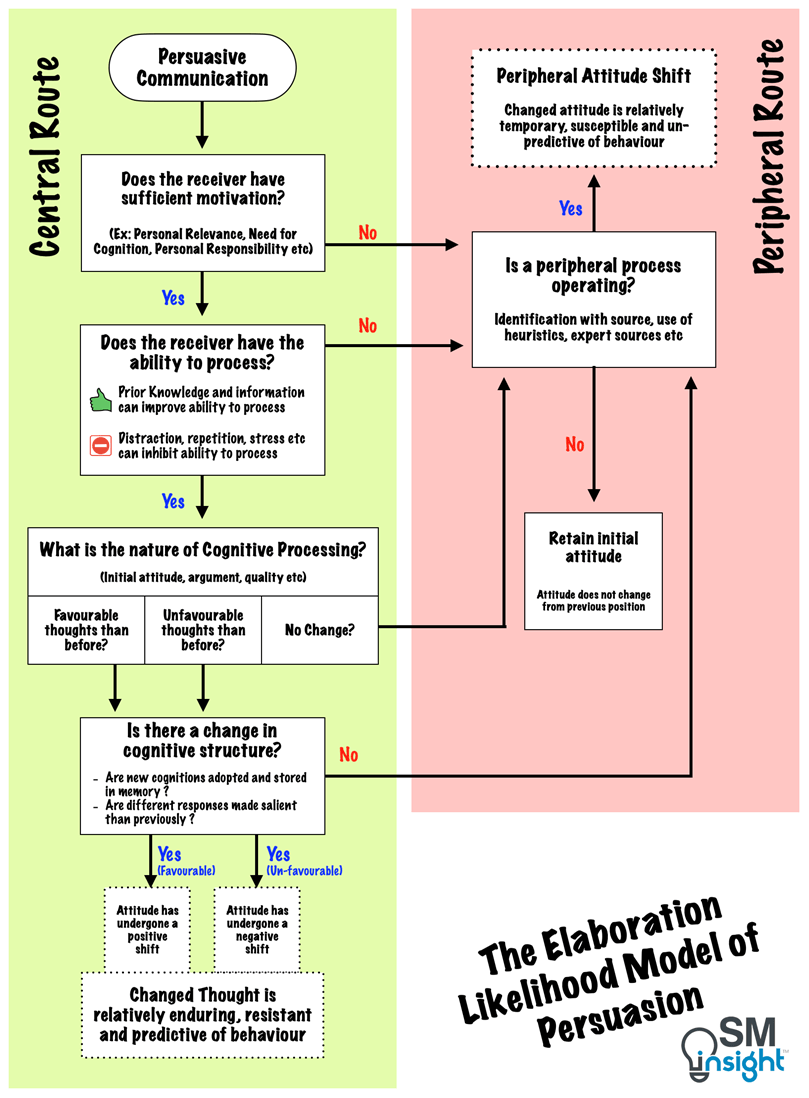

In order to resolve these fundamental questions, the Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion (ELM) was developed by Richard E. Petty and John Cacioppo in the 1980s.[2]

ELM is a comprehensive framework for organizing, categorizing, and understanding the basic processes underlying the effectiveness of persuasive communications.

The Elaboration Continuum

The following definitions in the context of ELM are important moving forward:

Attitude: A general evaluation held by a person about themselves, others, objects, and issues.

Influence: A change in evaluation held by a person.

Persuasion: Any change in attitude that results from exposure to a communication.

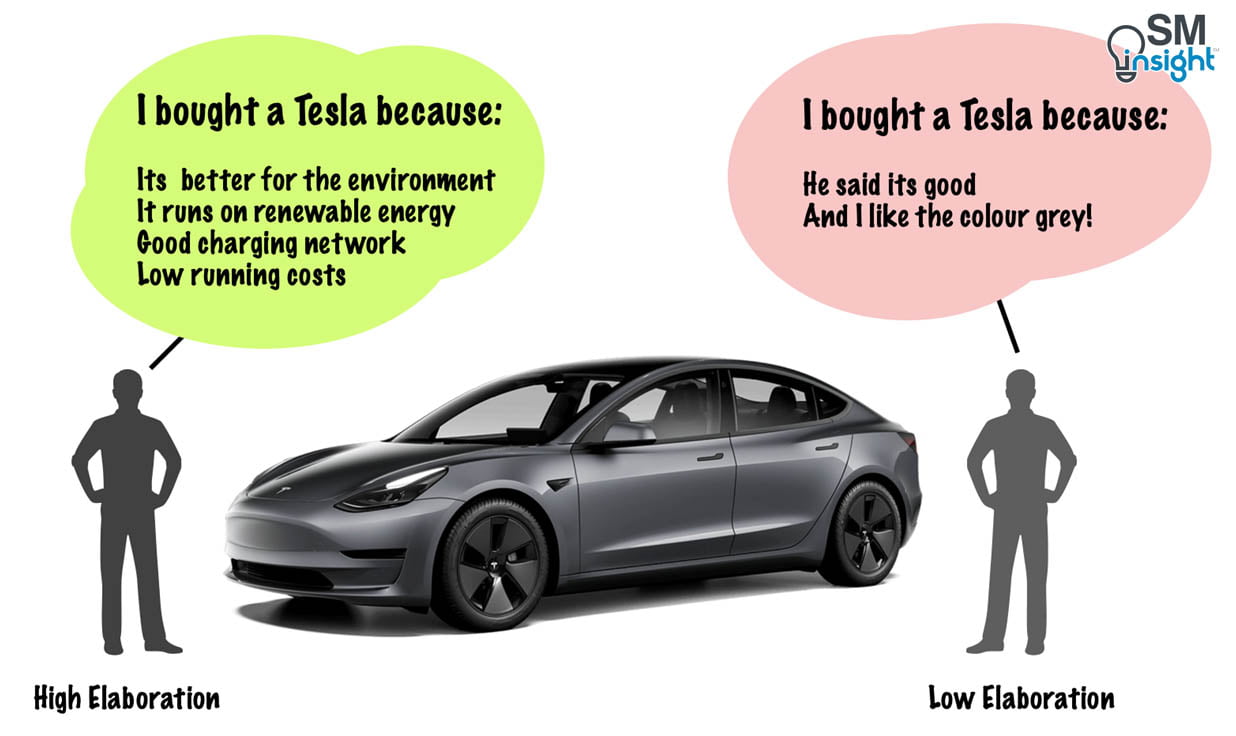

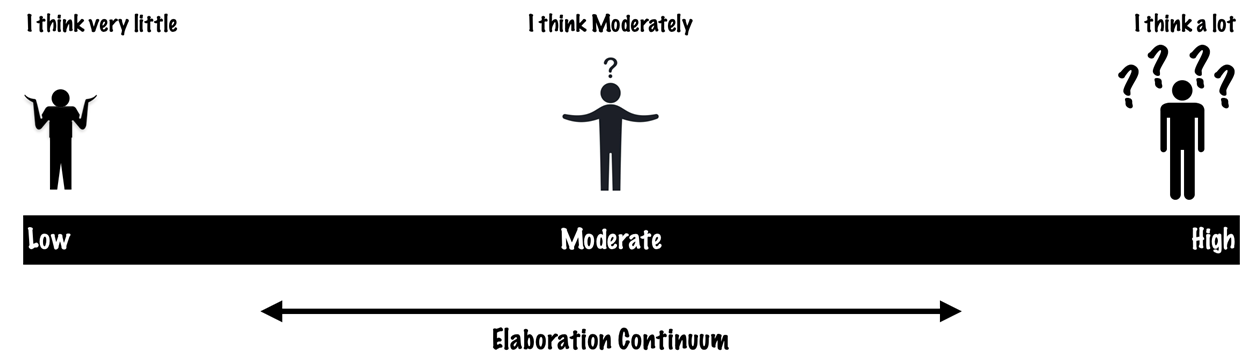

ELM assumes that individuals can differ in how carefully and extensively they think about a particular subject – a persuasive communication or an attitude.

The amount of elaboration (or thinking about the relevant message or issue) can vary continuously from very low to very high and is determined by a combination of individual differences and situational factors.

Thus, the amount of thinking people engage in goes a long way in explaining how they will be persuaded (if they are persuaded at all).

While individuals can think a great deal about persuasive communication, they might still fail to consider the merits of a particular message or attitude. The amount of thinking per se is not synonymous with elaboration likelihood.

Thus, several individual differences and situational factors impact the likelihood that a person will think carefully about a persuasive message or issue.

The Elaboration Likelihood

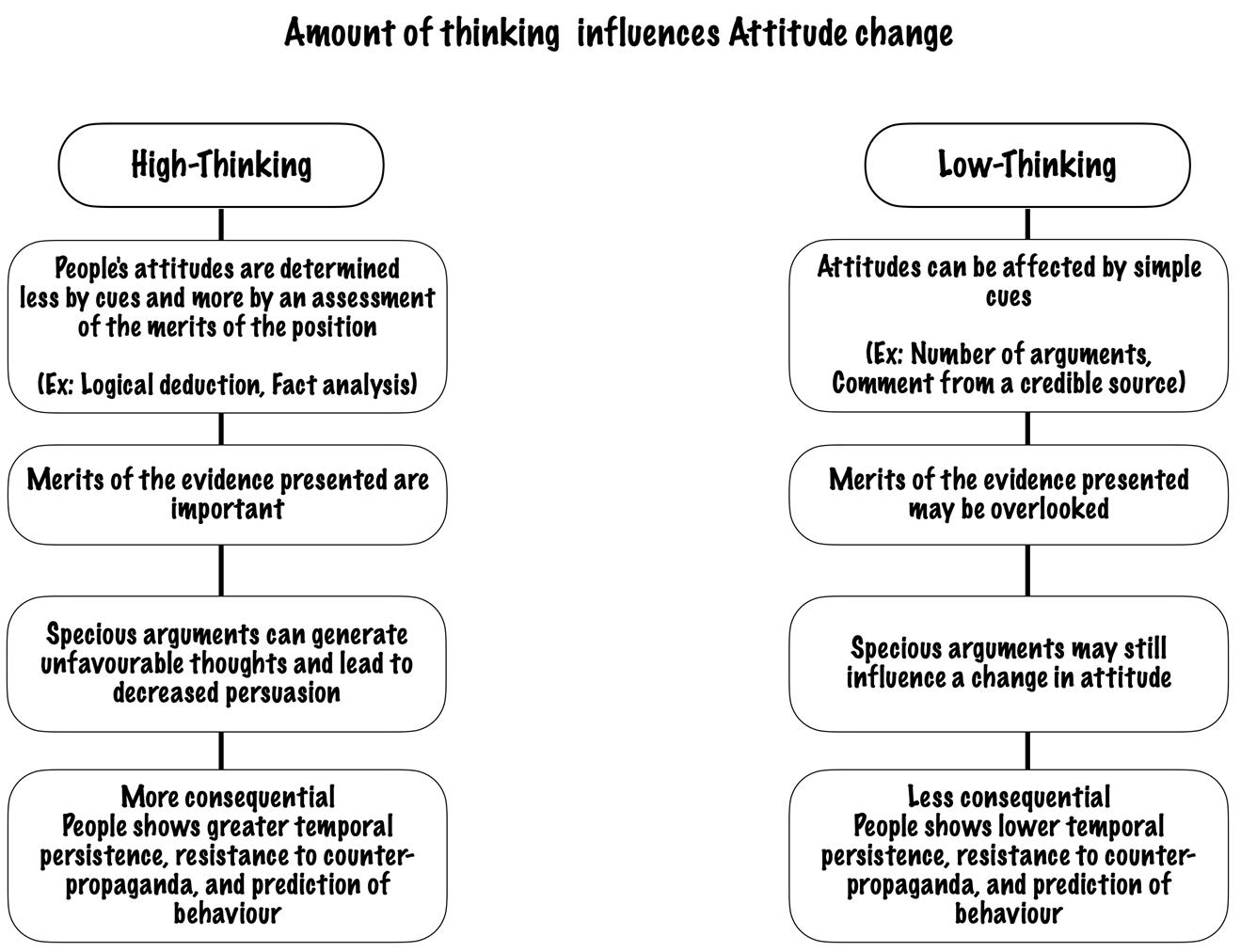

According to the ELM, understanding the variables that affect thinking is important for several reasons.

For example, the amount of thinking a person engages in determines what process is responsible for persuasion (explained later) and tends to be less or more consequential:

Broadly, the factors that affect the extent of thinking can be classified as motivational or related to the ability to think (although some factors may relate to both).

Motivational Factors

Among the motivational factors, the first factor is personal relevance which has received

the most attention. It is generally decided by three elements:

- Geographic location: Whether the issue is of local importance.

- Time: whether the issue affects the message recipient sooner or in the distant future.

- Whether the recipient faces an imminent decision about the issue.

When relevance is high, the persuasion message relates directly to the recipient and stands to impact his or her life in some way.

For example, people process consumer advertisements more carefully when the product is available in their home city than when it is available only in far-away locales.

A second factor is the Need For Cognition (NC). People with a high NC simply enjoy thinking while people low in NC tend to engage in deep thought only when absolutely required.

Hence, individuals with a high NC have an especially high elaboration likelihood, whereas individuals with a low NC generally do not process persuasive messages very carefully and are more dependent on simple cues in the persuasion context.

A third such factor is the psychological consistency. People strive to perceive their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors as consistent with one another, and experience discomfort when considering an inconsistency between them.

Attitudinal ambivalence can arise when an individual has conflicting beliefs about an attitude object.

For instance, a person might enjoy the taste of an ice cream but dislike the fact that it is high in saturated fat and contributes to weight gain. Such ambivalence can lead to increases in message processing.

Also, more recent research has suggested that ambivalent individuals are more likely to elaborate upon pro-attitudinal information rather than counter-attitudinal information to reduce ambivalence.[1]

A fourth factor is the incidental emotion a recipient experiences during persuasion. Sadness (because it signals uncertainty) has been associated with careful information processing while happiness has been associated with relatively shallow, heuristic processing.

Ability Factors

A number of ability factors also influence the likelihood that a person will carefully elaborate a persuasive message.

The first and most obvious example is message repetition which makes people better comprehend, scrutinize, and recall the arguments in a persuasive communication.

Possessing adequate attentional resources is the second factor. For example, distraction reduces the ability to distinguish strong from weak arguments.

Knowledge and experience too are contributing factors. People are better able to comprehend and scrutinize message arguments when they possess a high degree of knowledge and experience regarding the message’s topic.

Thus, having a high elaboration likelihood requires both high motivation and an ability to think.

Two Routes to Persuasion

ELM holds that at the end points of the elaboration likelihood continuum, people can be persuaded via one of two processing modes called the Central Route and the Peripheral Route.

These two routes form the crux of the ELM.

The “central route” is that which likely occurred as a result of a person’s careful and thoughtful consideration of the true merits of the information.

The “peripheral route” is that which likely occurred because of some simple cue in the persuasion context that induced change without necessitating scrutiny of the central merits presented in the information.

The likelihood that one or the other route will predominate in any given situation is determined by the perceiver’s elaboration likelihood.

Within each of these two routes, a number of more specific mechanisms can lead to attitude change, as shown:

(Source: Elaborative Likelihood Model – R Petty & J Cacioppo[2])

Peripheral Route to Persuasion

In the peripheral route, a person does not think much about persuasive communication. The level of elaboration is low, and he/she is likely to be persuaded by one of several low-effort mechanisms.

A classic example of a peripheral route persuasion is an advert in which an attractive

supermodel promotes a product:

By encouraging viewers to develop an association between the (positively valued) supermodel and the (initially neutral) product, the ad’s developers capitalize on consistency, balance, and process.

One of the mechanisms producing persuasion in this case is called classical conditioning where people develop mental representations without conscious intention or awareness. For example: “I like myself, I like the supermodel and she likes the car and so should I”.

The development of such mental representations, in many cases, can occur without conscious intention or awareness.[1]

Another such mechanism at play is misattribution in which the target audience might reason that they are likely to enjoy products that people they like also enjoy, thereby developing a more favorable attitude toward the car/brand that the supermodel endorses.

Each of the above mechanisms involves little cognitive effort in assessing the information relevant to the merits of the attitude object but leads to (at least temporary) attitude change in the direction favored by the advertisement’s developers.

Central Route to Persuasion

In the central route, individuals carefully scrutinize the elements of the persuasive message to determine whether the proposal makes sense and will benefit in some way.

In this route, an individual focuses on the strength of the message arguments, which are pieces of information in the communication intended to provide evidence for the communicator’s point of view.

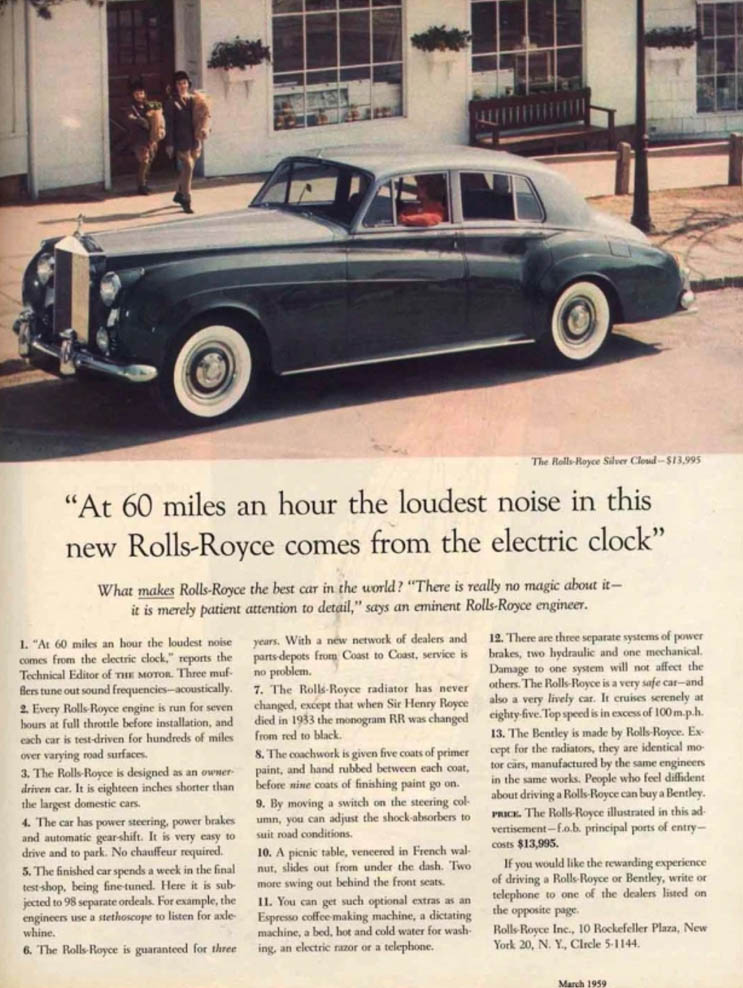

For example, consider the Rolls-Royce advert from 1958. In contrast to the earlier BMW example, this ad takes the central route of persuasion by providing specific arguments as to why the brand’s cars are “the best cars in the world”.

In the central route, Strong arguments can generate predominantly favorable thoughts in response to the message and lead to an attitude change. Likewise, weak arguments could generate unfavorable thoughts without an attitude change or even a change in the opposite direction. Hence, argument quality plays an important role.

But what determines the strength of message arguments?

Research has suggested a few key factors that render some arguments better than others:

First, people are more likely to have a favorable attitude towards an argument that emphasizes positive outcomes and portrays them as likely to happen.

Secondly, the more unique and important the dimension the argument addresses, the higher the impact it may have.

Finally, strong arguments tend to relate consistently with one another in the context of the overall message. They are cogent, coherent, and compelling. Weak arguments, in contrast, are illogical and self-contradictory.

Although the central route of persuasion is often regarded as a route for impartially considering message arguments, it is not immune to biased interpretation and assessment of information.

Several factors contribute to this bias, including:

- Favorable evaluation of arguments aligning with pre-existing attitudes.

- Emotional states influencing recipients’ assessments.

- Favorable processing of arguments when feeling happy.

- More focus on sad consequences when feeling sad.

Timing is also important when it comes to thought validation. A persuasion variable tends to influence thought confidence depending on whether it is introduced before, during or after the message.

For example, when people learn that a message comes from an expert before processing it, they pay more attention to the message. If they learn about the source’s expertise after processing the message, they trust their own thoughts more.

In both cases, the positivity or negativity of their thoughts has a stronger impact on their attitudes when the source is seen as highly knowledgeable but for different reasons.

Consequences of the route to persuasion

The elaboration route used to form or change an attitude has a number of ramifications.

An attitude that results from central route processes tends to be more stable over time, resistant to counterarguments and is likely to guide (and bias) thinking in a pro-attitudinal way. More importantly, it leads to attitude-consistent behavior.

This represents the feature of a “strong attitude” and increases the chances of eliciting sustained behavior change.

Despite the obvious benefits, however, shaping attitudes through the central route is difficult to achieve given the higher elaboration demands that are placed on the target audience.

The temptation to focus on producing attitudes through a less demanding peripheral route is often strong but can lead to “hollow victory”. But such an attitude tends to be less enduring, vulnerable to counterarguments and is less likely to lead to attitude-consistent behavior.

Nevertheless, a peripheral approach can be quite powerful in the short term, especially when an immediate change is all that is required. But, over time, the emotions dissipate, feelings can change, and cues can become disassociated from the message.

Thus, a key contribution of the ELM is the proposition that it is insufficient to know simply what a person’s attitude is or how much it has changed. It is also important to know how the attitude was changed or formed in the first place.

“It is insufficient to know simply what a person’s attitude is or how much it has changed. It is also important to know how the attitude was changed or formed in the first place.”

There are two key reasons for attitudes based on the central route to produce stronger attitudes.

First, operative factors such as thoughtful attitudes are more accessible and likely to come to mind when needed.

Second, metacognitive factors such as attitudes that people have thought a lot about are held with greater certainty and are thus more likely to be viewed as useful guides to action.[6]

Using ELM in practice

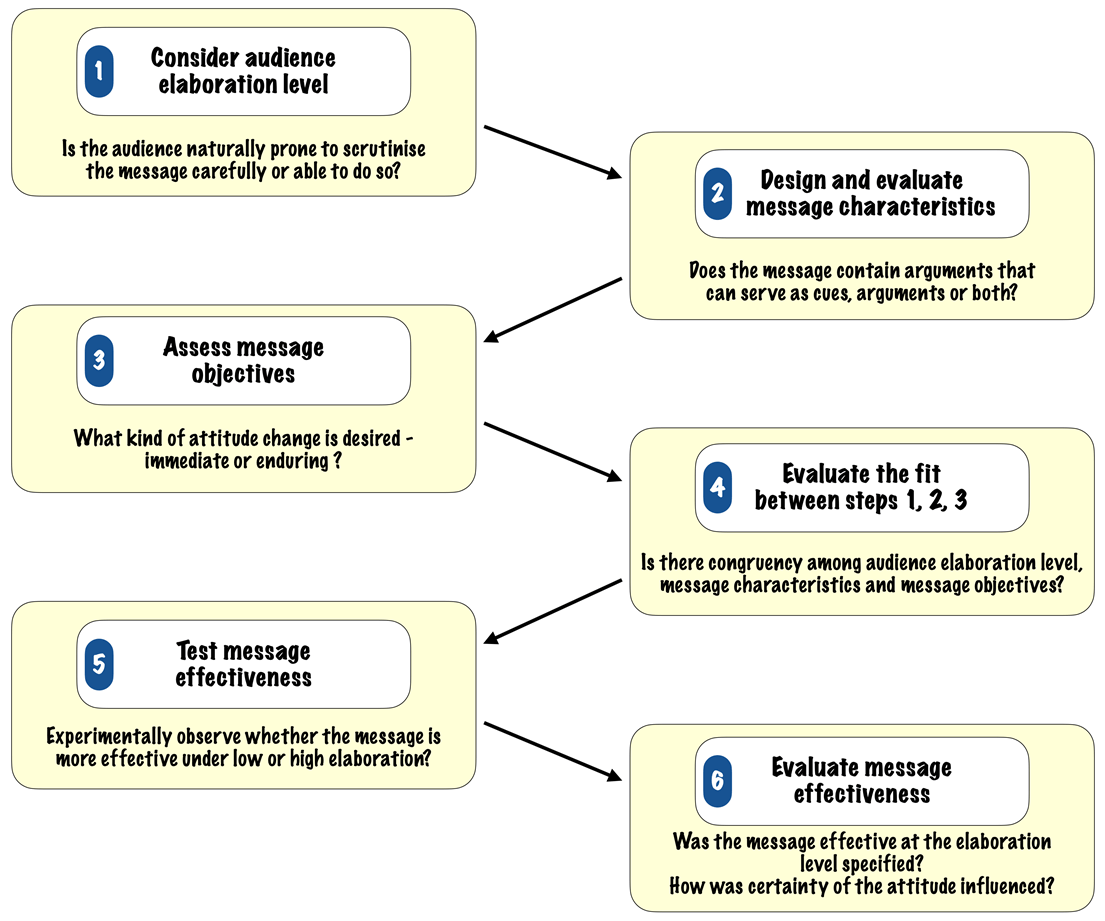

ELM researchers Richard Petty and Derek Rucker have proposed a six-step process that can be applied when developing practical communication interventions to influence behavior:[7]

1. Consider the audience elaboration level

This first step is to make a rough estimate of the likely elaboration level of the audience.

Having a basic understanding of the elaboration level provides insight as to whether a persuasion message will involve careful scrutiny or will be processed more peripherally.

The estimated elaboration level need not be very accurate at this stage as it can be examined empirically and corrected in Step 5.

2. Design and Evaluate Message Characteristics

This step is to consider what information will be conveyed in the message and whether this information will be processed as strong arguments, powerful peripheral cues, or both.

Available options for developing and communicating a message that fits with the audience’s elaboration level must be examined. These options may involve, for example, developing substantive arguments that can withstand intense scrutiny or components that can serve as simple cues such as a credible and engaging message source.

Certain components of a message can cater to both central and peripheral route processing options.

If a celebrity is used in a campaign as a simple cue, their experience related to the message subject could move beyond a cue status and represent a strong argument.

For example, Robert Downey Jr. – the man behind film favorites like Iron Man is a role model for millions and was once fighting a public substance abuse battle.

If he were to promote an anti-drug campaign, the fact that he went through the addiction himself would qualify as both, a cue (due to celebrity status) and a strong argument (due to his history with addiction)[8]

3. Assess message objectives

This step involves assessing what kind of attitude change is desired – whether enduring or only an immediate change.

This decides if a persuasion message should follow a central or peripheral route. The former is more likely to produce an enduring change, while the latter is more likely to produce an immediate but short-term change.

Both have their own advantages and disadvantages depending on the situation.

For example, a public service announcement directed at young people about the dangers of smoking might be developed with the explicit goal of creating an enduring attitude change.

Conversely, a warning message about the various dangers of overdosing on a particular prescription drug may require only a short-term attitude change.

Given the obvious advantages of the central route, the question may then arise whether using the peripheral route should ever be considered. Despite the disadvantages, the peripheral route may sometimes be a necessity:

In many cases, the target audience lacks either the motivation or the ability to process the message, and providing either or both may not be an option.

For example, the audience (who are to be warned about prescription drug overdose) may not have the motivation or the ability to understand how overdose affects them, or the amount of space allowed for warning labels may necessitate the use of peripheral cues.

4. Evaluate audience elaboration, message characteristics, and message objectives

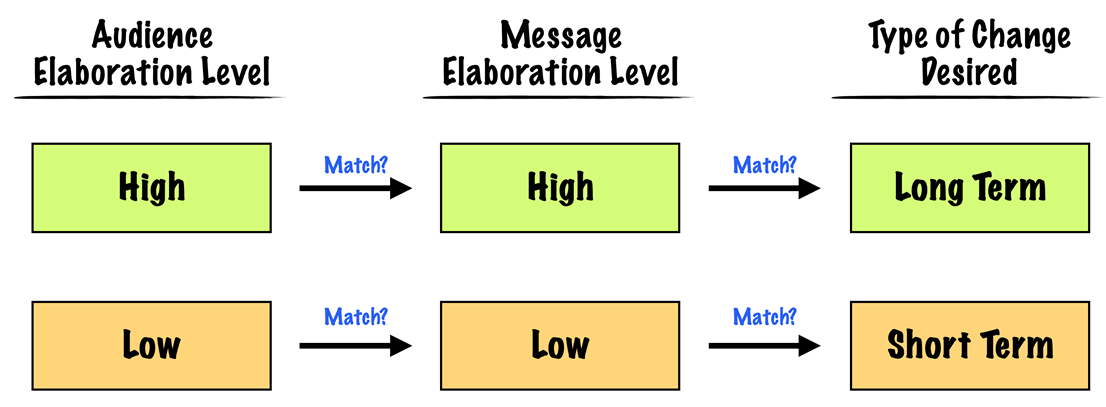

This step involves examining whether there is a fit between the audience elaboration level and the information in the message and whether this creates the type of attitude change in line with the message objective.

First, the audience elaboration level (low, high) needs to match the level of elaboration at which the message is designed to be effective (low, high).

If there is an apparent match between the two, it should then be considered whether the type of attitude change produces the desired consequences (e.g., short-term, or long-term change).

If there is not a match between the three, actions should be taken to change either the elaboration level of the target audience (e.g., make the communication context less distracting; make the message more personally relevant) or the type of information contained in a message to match the level of elaboration for the desired consequences.

When evaluating fit, it’s crucial to emphasize a key concept of the ELM, which suggests that a single variable can influence persuasion in multiple ways.

In some cases, the same variable (e.g., source credibility, mood) may exert influence under both low and high elaboration conditions, albeit for different reasons. A single variable may for example:

- Serving as an argument

- Serving as a simple cue

- Influencing properties of participants’ thoughts (amount, degree of confidence etc.)

This ability of a variable to play several roles can have different influences depending on the context and elaboration level.

Thus, in assessing fit, it is important not only to identify the variables in the communication but also to be sure that these variables produce the correct effects on the basis of the level of audience elaboration.

5. Test Message Effectiveness

This step involves experimentally examining the effectiveness of the message in persuading

the target audience and may involve the following steps:

First, compare the effect that the message has produced vs. a no-message situation or an alternative message situation.

For example, presenting one set of audience with a brochure containing the message and another set of audience with a brochure on an unrelated topic and then varying the level of elaboration.

Second, gauge consumers’ attitudes, attitude certainty, and thoughts about the message topic.

Gauging attitudes gives an overall sense of whether the message was effective in changing attitudes relative to the no-message control and reveals which message creates more desirable attitudes.

Measuring certainty helps assess whether attitudes are likely to be persistent, resistant, and predictive of behavior while gauging thoughts helps understand why consumers hold their attitudes.

If resources permit, attitudes should be examined not only immediately after message presentation but at several later points in time as well. This serves as a further check of the strength of the attitude change.

6. Evaluate Message Effectiveness

With data on attitudes, thoughts, and certainty (from the previous step), this step involves making a final determination about whether the message was effective.

The following questions serve as checkpoints:

- Did the audience attend to and process the strong arguments?

- Did they rely on cues?

- Were the resulting attitudes held with certainty?

If the message has produced desirable consequences, it is ready to be delivered to the

public. If not, then the potential problems need reconsideration.

Applications of ELM

ELM has found applications in various sectors, some of which are:

Education: In education, ELM is used to design effective instructional materials and strategies that match the learners’ motivation and ability to process information.

It has helped teachers decide when to use more interactive and engaging methods (such as games, simulations, or discussions) or more passive and straightforward methods (such as lectures, readings, or videos) to facilitate learning outcomes.[9]

Health: In healthcare, ELM is used to create persuasive health messages and campaigns that influence people’s attitudes and behaviors regarding health issues.

Particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, the model was extensively used to design persuasive messages around vaccination.[10], [11]

The model has helped health communicators choose the appropriate source, message, and channel to appeal to different audiences based on their level of involvement and interest in the health topic.

Politics: In politics, ELM is used to understand how communication affects public opinion and voting behavior. It has helped political candidates and parties craft persuasive speeches and advertisements that target voters through either central or peripheral cues, depending on their level of political awareness and sophistication.[12]

Business: In business, ELM’s role especially in marketing and sales has been pivotal. The model has provided a better understanding of how consumers process and respond to persuasive messages.

It has helped marketers and sales teams tailor their messages and strategies to different segments of consumers based on their level of involvement and knowledge of the product or service.

Limitations of ELM

While the usefulness of ELM as a framework for conceptualizing attitude formation and change is widely acknowledged; it does have limitations and criticisms:[13]

Unclear cue classification: ELM struggles to clearly classify central and peripheral cues, making it challenging for marketers to predict which cues will be processed in which way.

Interactive Processing: The model presents central and peripheral processing as alternatives. Whether they interact or have separate main effects in influencing attitudes remains unexplored. Some studies have argued that the central and peripheral cues work in combination despite the variables of motivation and ability.[14]

Strength of attitudes: Few studies have contested the claim that attitudes formed through peripheral processing are less durable and predictive of behavior compared to those formed through central processing.[15]

Diverse effects of peripheral processing: ELM underscores the varied nature of peripheral processing which can involve cognitive shortcuts when individuals rely on heuristics due to low motivation, or direct affective responses where emotions drive attitudes.

These different processes lead to diverse outcomes, raising questions about the strength and durability of attitudes formed through peripheral processing.

Central processor in the absence of useful information: When motivation is high, but useful central cues are absent, the audience may rely on peripheral cues and potentially elaborate on them. This raises questions about the durability and confidence of such attitudes.

Sources

1. “The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion: Thoughtful and non-thoughtful social influence”. Wagner, Benjamin C and Petty, Richard E., https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2011-20402-004. Accessed 08 Sep 2023

2. “The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion”. Richard E Petty and John T Cacioppo, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270271600_The_Elaboration_Likelihood_Model_of_Persuasion. Accessed 08 Sep 2023

3. “Model 3”. Tesla, https://www.tesla.com/model3/design#overview. Accessed 11 Sep 2023

4. “Dare to be you”. BMW, https://www.bmw.com/en/magazine/automotive-life/naomi-campbell-bmw-xm-dare-to-be-you.html. Accessed 08 Sep 2023

5. “GREAT ADVERTISING EXAMPLE”. Adwaycreative, https://www.adwaycreative.eu/good-advertising-example/. Accessed 08 Sep 2023

6. “Elaboration as a determinant of attitude strength”. Petty, R. E., Haugtvedt, C. P., & Smith, S. M. (1995), https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1995-98997-005. Accessed 10 Sep 2023

7. “Increasing the Effectiveness of Communications to Consumers: Recommendations Based on Elaboration Likelihood and Attitude Certainty Perspectives”. Richard Petty and Derek Rucker, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247837464_Increasing_the_Effectiveness_of_Communications_to_Consumers_Recommendations_Based_on_Elaboration_Likelihood_and_Attitude_Certainty_Perspectives. Accessed 08 Sep 2023

8. “Robert Downey Jr. Proves You Can Banish Alcohol and Substance Abuse”. Absoluteadvocacy, https://www.absoluteadvocacy.org/robert-downey-fights-addiction/. Accessed 11 Sep 2023

9. “How Elaboration Likelihood Model Can Inform Instructional Design”. Adam Gavarkovs, https://elearningindustry.com/elaboration-likelihood-model-can-inform-instructional-design. Accessed 12 Sep 2023

10. “The Association Between Dissemination and Characteristics of Pro-/Anti-COVID-19 Vaccine Messages on Twitter: Application of the Elaboration Likelihood Model”. National Library of Medicine, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9239316/. Accessed 12 Sep 2023

11. “Persuasion amidst a pandemic: Insights from the Elaboration Likelihood Model”. European Review of Social Psychology, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10463283.2021.1964744. Accessed 12 Sep 2023

12. “Applying the Elaboration Likelihood Model to Voting”. Terry Chmielewski, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290799823_Applying_the_Elaboration_Likelihood_Model_to_Voting. Accessed 12 Sep 2023

13. “The Elaboration Likelihood Model: Limitations and Extensions in Marketing”. The Association for Consumer Research, https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/6427/volumes/v12/NA-12. Accessed 11 Sep 2023

14. “The Combined Influence Hypothesis: Central and Peripheral Antecedents of Attitude toward the Ad”. Kenneth R. Lord, Myung-Soo Lee & Paul L. Sauer, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00913367.1995.10673469. Accessed 11 Sep 2023

15. “Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences”. Zajonc, R. B. (1980), https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1980-09733-001. Accessed 11 Sep 2023