The sheer volume of metrics an organization can measure or monitor can be overwhelming.

Trying to focus on too many of them is not only impractical, unnecessary, and sub-optimal but can also undermine success.

In an increasingly complex world, identifying data needed for executive decision-making can be hard. Geared with layers of information-gathering technology, executives find themselves inundated by a continuous stream of information but struggle to derive the insights needed to make sound decisions.

Valuable content is often trapped in organizational silos, lost in transit between systems, bypassed by inadequately tuned data collection systems, or presented in formats that are too hard to read. These difficulties arise due to poorly designed management information systems that fail to deliver pertinent data for executive decision-making.

Critical Success Factors (CSF) is an approach that attempts to overcome these limitations by defining a few key areas in which the organization must be truly successful. These are the areas where “things cannot go wrong”. They are also the areas in which satisfactory results will ensure a successful competitive performance.

Origin of CSF and the techniques it replaced

The concept of success factors was first discussed by D. Ronald Daniel of McKinsey & Company in 1961 [1] and further developed into critical success factors by John F. Rockart of the MIT Sloan School of Management in 1979 [2].

Before CSFs became popular, businesses mainly relied on four main ways of determining executive information needs: the by-product technique; the null approach; the key indicator system; and the total study process.

It is worthwhile to understand the benefits and shortcomings of these methods to appreciate the improvements brought by the CSF approach:

By-product Technique

Popular during the beginning of the computer era, the by-product technique focused on automating routine paperwork processing, such as payroll, accounts payable, billing, and inventory. The information generated by such systems was then used for executive reporting (as a by-product).

Since paperwork was the main driving force, this resulted in a large number of reports, many of which did not address the specific needs of the top executives. Automating paperwork brought efficiency, however, its alignment with strategic organizational needs was missing.

Many reports reaching the top were versions of what lower-level executives felt were useful. Some routine reports were also a result of a previous one-time request for information concerning a particular matter initiated by a top executive in the past that was no longer relevant.

With several limitations, the by-product technique could not be used as a stand-alone tool and was often supported by other methods to obtain more targeted and useful information.

The Null Approach

Organizations that took the null approach believed that the activities of their top executives were dynamic and ever-changing and that the exact information needed to deal with such changing events could not be determined in advance.

Executives in such organizations, therefore, depended on future-oriented, rapidly assembled, most often subjective, and informal information delivered by word of mouth from their trusted advisers.

A limitation of this approach was its failure to automate information that could and should have been regularly supplied to the chief executive. It also did not create a distinction between formal (the type that can be automated) and informal data.

Key indicator system

The key indicator system came close to the best practices followed in modern management reporting and was based on three concepts:

- Defining key indicators: identifying a set of indicators that best reflect the health of the business and designing information collection around those indicators.

- Exception reporting: focusing on only those indicators where performance was significantly different from expected results. An executive could choose whether to peruse all available data or focus only where immediate attention was needed.

- Expand access: since the indicators were clearly defined, they could then be displayed visually across the organization for more effective consumption.

While the key indicator system was an effective reporting technique compared to other methods of its time, its emphasis remained limited to financial data. ‘Profit and loss,’ ‘balance sheet,’ and financial ratios were important, yet they could not convey other crucial information necessary for executive decision-making.

Total study process

First developed by IBM, the approach involved querying a widespread sample of managers about their total information needs and comparing the results with existing information systems. Subsystems necessary to provide those missing information were then identified and assigned priorities for development.

The approach helped overcome the limitations of single systems that evolved to address specific use cases in relative isolation from each other and with little attention to management information needs.

IBM’s Business Systems Planning (BSP) [3] methodology was the most widely used total study process that aimed at a top-down analysis of the information needs of an organization.

The total study process was expensive in terms of staff time and all-inclusive in terms of scope. Because the amount of data and opinions gathered was staggering, it was difficult to determine the correct level of aggregation for decision-making, data gathering, and analysis.

Advantages and limitations

Each of the four current procedures just discussed had its advantages and disadvantages:

| Approach | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| The By-product technique | Gets paperwork processed inexpensively. | Not much useful managerial information.Managers may consider data from a single function in isolation from other meaningful data. |

| The Null Approach | Emphasis on the changeability, diversity, and information needs of a top executive.Avoids building useless information systems. | Attaches too much importance to an executive’s person-to-person role.Overlooks the role of management control which can be (at least partially) served by routine, computer-based reporting. |

| The Key indicator system | Provides a significant amount of useful information that is objective, quantifiable, and can be automated. | Focuses on being financially all-inclusive rather than on an executive’s specific needs.Fails to assist executives in thinking through their real information needs. |

| The total study process | Enables comprehensive information gathering and can pinpoint missing systems. | Expensive.A huge amount of data collected leads to difficulties in developing reporting systems tailored to individual manager’s needs. |

CSF: a better method to address executive information needs

To overcome the shortcomings of the above approaches, the CSF method focuses on individual managers and each manager’s current information needs – both hard and soft. It considers the fact that information needs can vary from manager to manager and that those needs can also change with time.

By propagating the idea that a company’s information system must be discriminating and selective, it focuses on ‘success factors’ – areas of activity that must receive constant and careful attention from management. Performance in those areas can then be continually measured, and information made available.

While good managers have been using CSFs implicitly and subconsciously, the approach attempts to make such factors explicit thereby letting them guide managerial priorities and resource allocation.

CSF’s place in the management process

While terms like goals and objectives have relatively precise definitions, the same is not true of CSFs. This is because what is (and is not) a CSF for a particular manager depends on subjective judgment and can only be arrived at after some thought. There are no clear rules which can assist a manager in finding her/his CSFs.

Every manager needs to determine their goals – which targets to shoot for. However, it is equally important to determine, in a consciously explicit manner, what the basic structural variables are that will most affect the attainment of those goals. These are the manager’s CSFs.

Once identified, these areas should receive constant and careful attention. The status of performance in each area should be continually measured and information should be made accessible for management’s use.

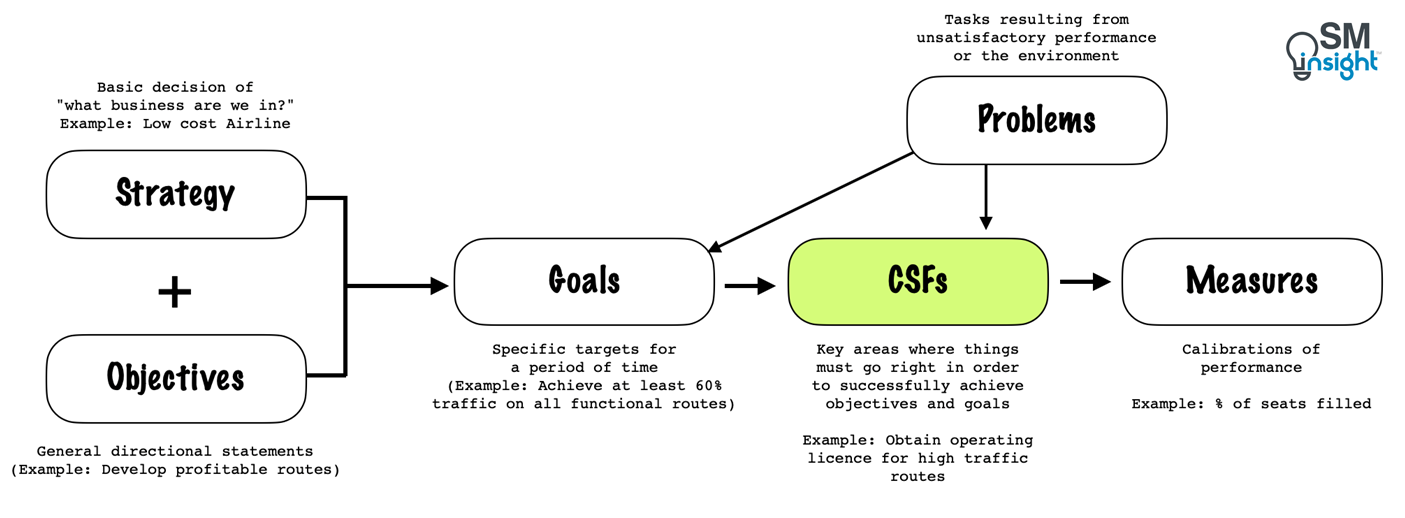

Like goals and objectives, CSFs appear at various levels in the management hierarchy. Hence it is important to understand its role and place within the managerial context:

A brief description of each of the terms is as follows:

- CSFs – are the limited number of areas in which satisfactory results will ensure a successful competitive performance for the individual, department, and organization. These are a few key areas where things must go right for the business to flourish and for the manager’s goals to be attained.

- Strategy – a pattern of missions, objectives, policies, and significant resource utilization plans stated in such a way as to define what business the company is in (or is to be in) and the kind of company it is or is to be.

Strategy also defines the product line, the markets and segments for which products are to be designed, the channels through which these markets will be reached, how the operation is to be financed, the profit objectives, the size of the organization, and the “image” which the organization will project. - Objectives – general statements about the directions in which a firm intends to go while not stating specific targets to be reached at various points in time.

- Goals – specific targets that are intended to be reached at a given point in time. (an operational transformation of one or more objectives)

- Measures – specific standards that allow the calibration of performance for each CSF, goal, or objective. These can be either “soft,” that is subjective and qualitative, or “hard,” that is objective and quantitative.

- Problems – specific tasks that become important because of unsatisfactory performance or environmental changes. Left unaddressed, they can affect the achievement of goals or performance in a CSF area.

Different managers, different CSFs

CSFs are linked to the specifics of a particular manager’s situation. They can constantly change depending on the industry dynamics, the competitive position of a firm and other situational factors (see next section).

Considering this, it is important to understand what CSFs are not:

- They are not a standard set of measures (more commonly known as “key indicators”) that can be applied to all divisions of a company.

- They are not limited to factors that can be reported solely using historical, aggregated accounting information. On the contrary, the CSF method looks at the world from a manager’s current operating viewpoint.

CSFs are the particular areas of major importance to a particular manager, in a particular division, at a particular point in time [4].

They demand specific and diverse situational measures, many of which must be evaluated through soft, subjective information not usually gathered in an explicit, formal way.

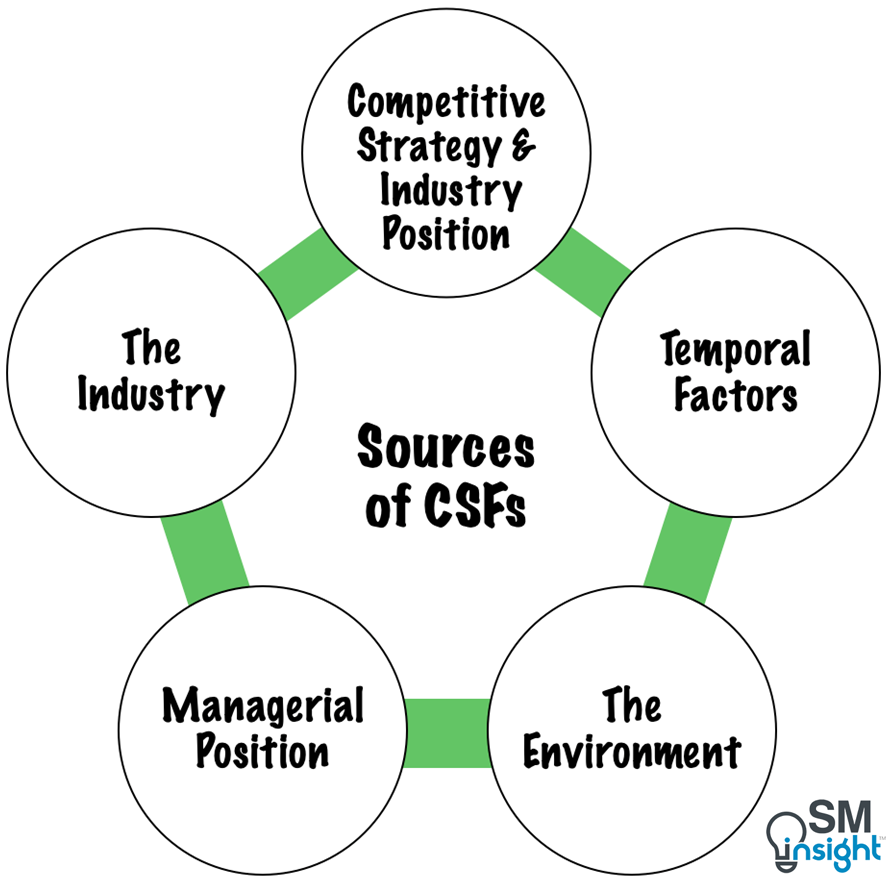

The five primary sources of CSFs

CSFs arise from the following five major sources.

The Industry

Every industry has a set of CSFs that are determined by the characteristics of the industry itself. Every company operating within that industry is forced to consider those factors.

For example, the supermarket industry has four industry-based CSFs: having the right product mix; having it on the shelves; having it advertised effectively to pull shoppers; and having it priced correctly.

Typically, profit margins are low, and supermarkets must pay attention to many other factors but these four areas form the core factors of successful operation.

Competitive strategy and position within the industry

Every company faces a unique individual situation which is determined by its history and competitive strategy. The resulting industry position can dictate some of the CSFs.

For example, a small company must almost always be concerned about protecting its niche. Similarly in an industry dominated by a single major firm, a CSF for all other players is used to monitor the leader’s strategies and their probable impacts.

Likewise, the geographic positioning of the company can also generate CSFs. For example, a business operating in a remote area may have transportation management as a CSF while the same may not be critical for urban businesses.

Environmental factors

Environmental factors are generally the areas over which an organization has little control. Economy and politics are the two obvious areas. Depending on the nature of the business, some companies can be sensitive to additional factors such as population trends, regulatory trends, and energy sources.

For example, Taiwan’s TSMC is by far the world’s leading semiconductor foundry. Because the bulk of TSMC’s operations are in Taiwan, it faces heightened geopolitical hazards. Both America and China covet its unmatched ability to make advanced chips. Should the tensions between the two nations escalate, TSMC can be negatively impacted by the fallout [5].

Temporal factors

These are areas of activities within an organization that become critical for a particular period of time due to something out of the ordinary taking place. Normally these areas

would not generate CSFs.

For example, when the Boeing 737 Max planes were grounded for over a year and a half following two crashes within five months, the company’s short-term CSFs were to address the root cause of the issue and regain public trust [5].

Managerial Position

Some of the CSFs are linked to the managerial position related to a function. For example, most manufacturing managers focus on product quality, inventory and efficiency.

Thus, an organization’s situation can change from time to time, and factors that are dealt with by executives as commonplace at one point may become CSFs at another. The key is to monitor these five sources continuously and clearly define the factors that are crucial to success during the period under consideration.

Dimensions of CSFs

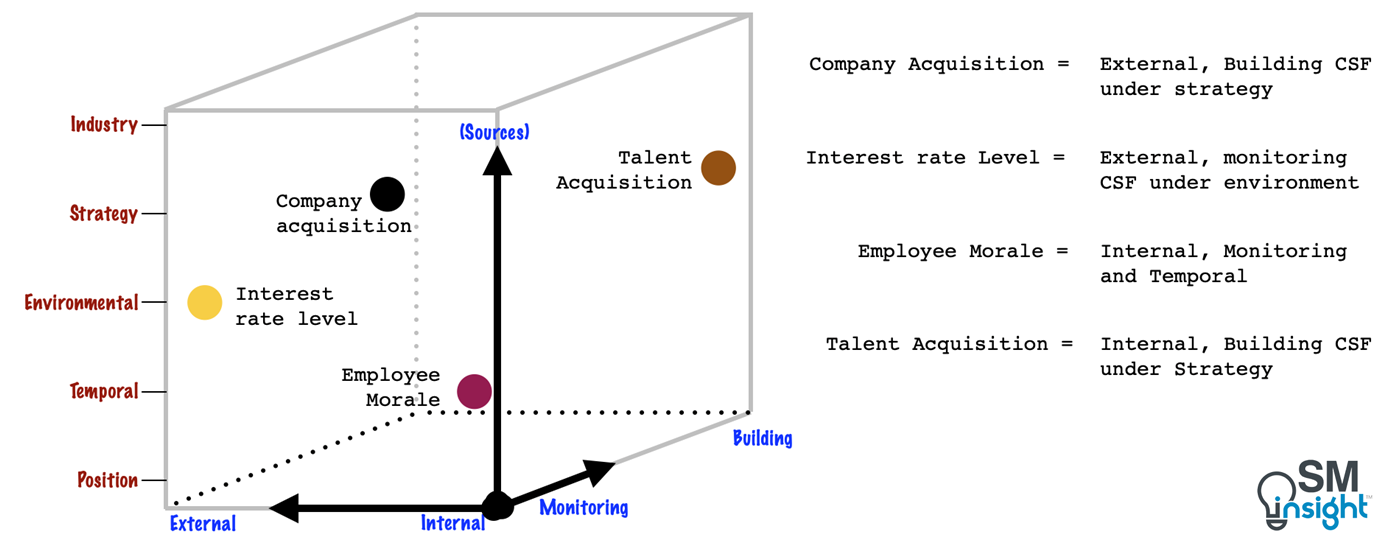

Any given CSF can be classified along three dimensions:

The three dimensions of classification (axis in the illustration above) are a useful way of visualizing the clustering of a particular manager’s CSFs and help in evaluating the results obtained from a CSF study.

For example, “company acquisition” depends on many external factors like the market and buyer interest, is a “building” CSF and depends on a firm’s strategy.

Source dimension

As shown in the illustration, the five sources of CSFs (already discussed) are also a dimension along which CSFs can be classified.

Internal versus external dimensions

Every manager will have internal CSFs relating to the department and the people they manage. They can include diverse factors ranging from human resource development to inventory control. The primary characteristic of such internal CSFs is that they deal with issues and situations within the manager’s sphere of influence and control.

In contrast, external CSFs pertain to situations outside the manager’s control.

For example, automobile manufacturers today depend extensively on electronic chips that enable most of their product features. The price and availability of such chips can vary due to external factors such as supply chain constraints, demand from other industries, and competitors’ relations with such suppliers – factors that are largely beyond a manager’s sphere of influence.

Monitoring versus building/adapting dimensions

Monitoring CSFs are those that focus on the continued scrutiny of existing situations. They help managers who are oriented toward emphasizing near-term operating results and invest considerable effort in tracking and guiding their organization’s performance.

Almost all managers have some monitoring CSFs – for example, financially oriented CSFs such as performance versus budget or cost incurred. Another monitoring-oriented CSF might be personnel turnover rates.

Building/adapting CSFs in contrast are useful to managers whose roles demand future-oriented planning and are relatively detached from day-to-day operations. They help implement major change programs aimed at adapting the organization to a perceived new environment.

Typical CSFs in these areas include successful implementation of major hiring and training efforts or new product development programs.

Managers will generally have a mix of both monitoring and building/adapting CSFs.

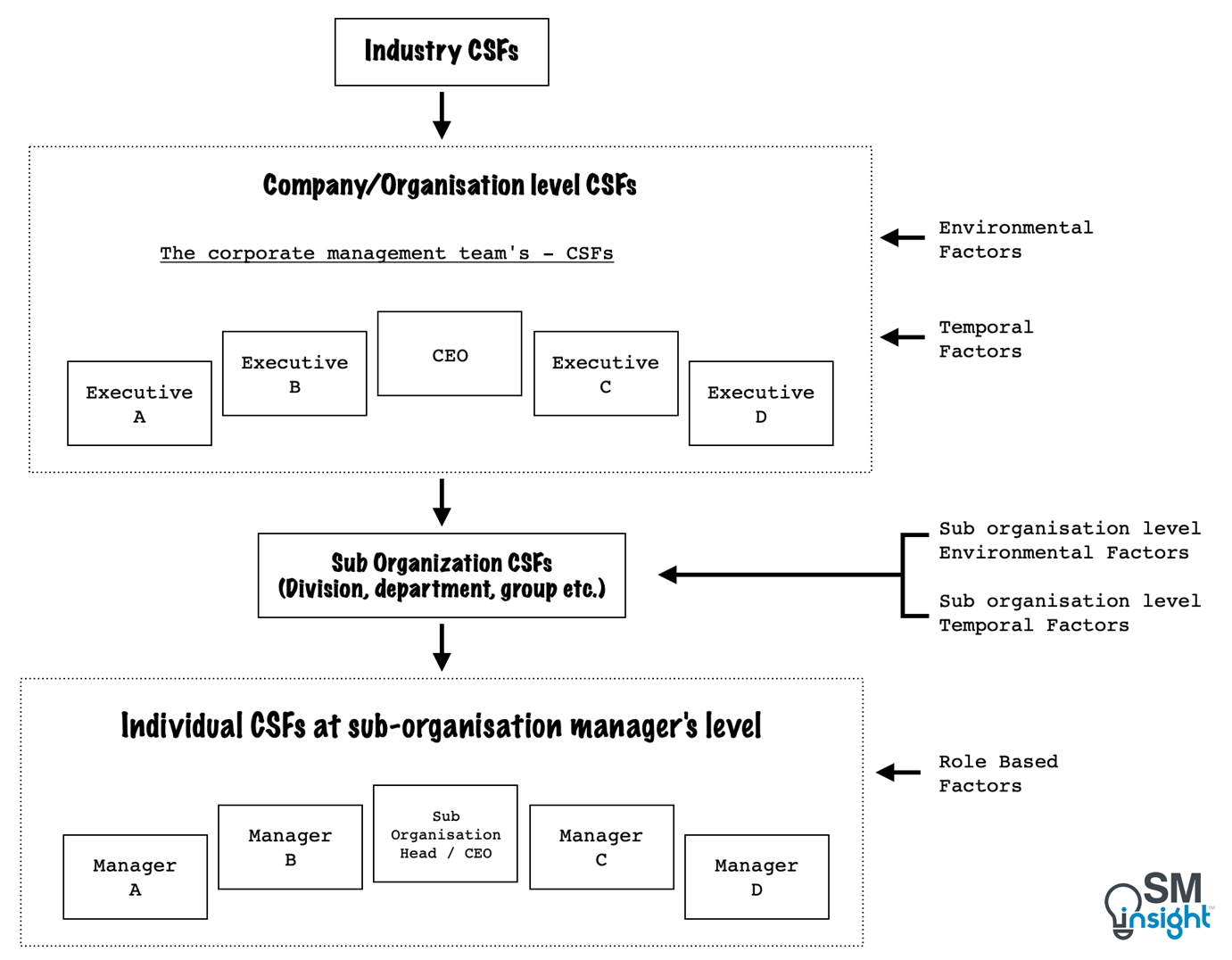

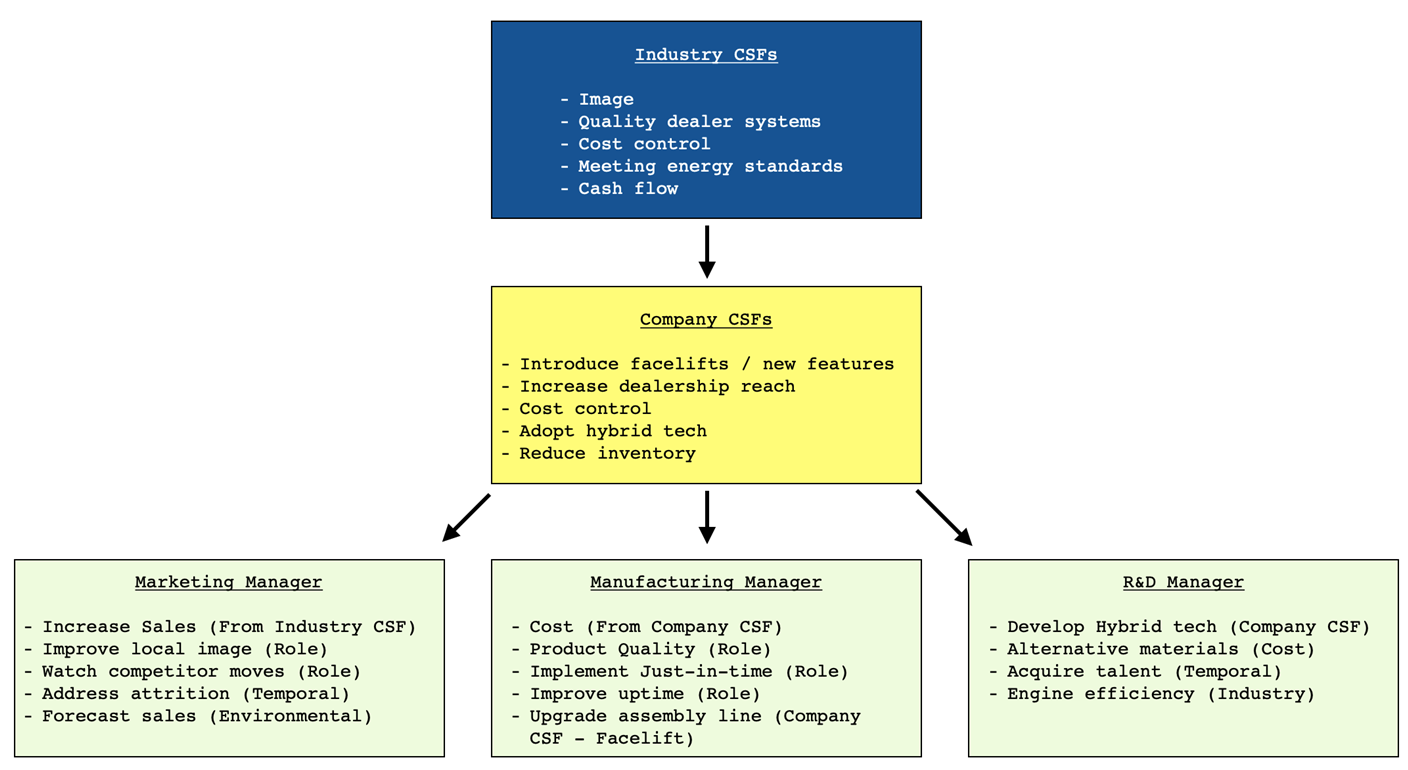

Hierarchy of CSFs

While an individual manager will have a set of own CSFs as the primary focus, from a company viewpoint, there can be four hierarchical levels, each of which influences the downline:

Industry CSFs

Industry forces determine the factors that lead to success and can heavily influence a firm’s strategy. Technical and competitive structure of the industry as well as the industry’s economic, political, and social environment can influence CSFs.

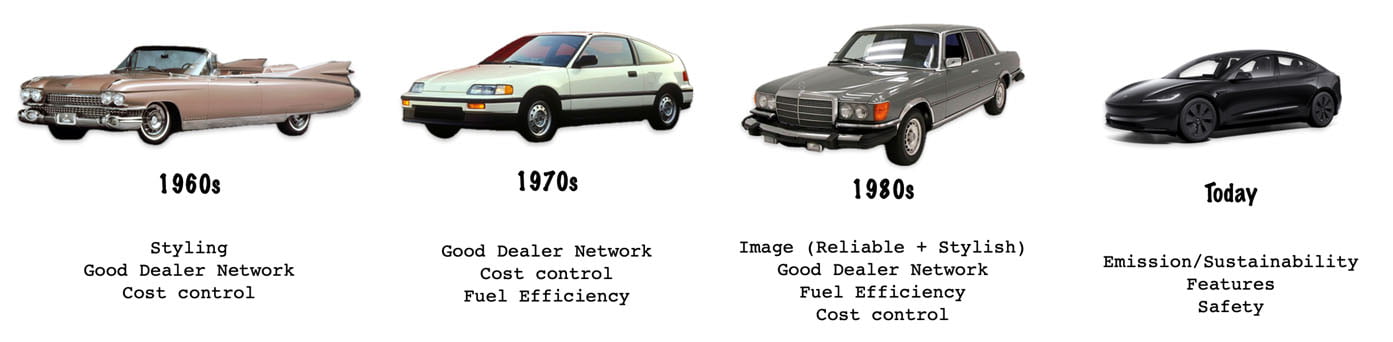

Consider the US automobile industry, for example. Factors that mattered in the 1960s are very different from what matters today:

Industry CSFs will change, sometimes in major ways and the pace of change can also vary depending on the industry environment. For example, CSFs for a cloud data service industry may change every six months vs five years for a pharmaceutical industry.

It is thus important to closely analyze industry factors, with particular attention to the changes that are taking place within an industry.

Company/Organization level CSFs

These are CSFs specific to a firm. While the industry CSFs are a major source of input, a firm’s CSF depends on other environmental, strategic, and temporal conditions specific to it. It also depends on what stage of the growth cycle a firm is in.

Even within the same industry, a firm’s situation can change from time to time. Factors that are normal at one time can become CSFs at another time. Company CSFs are decided primarily at the corporate level and can be different, or can have different priorities, for similar firms operating within the given industry.

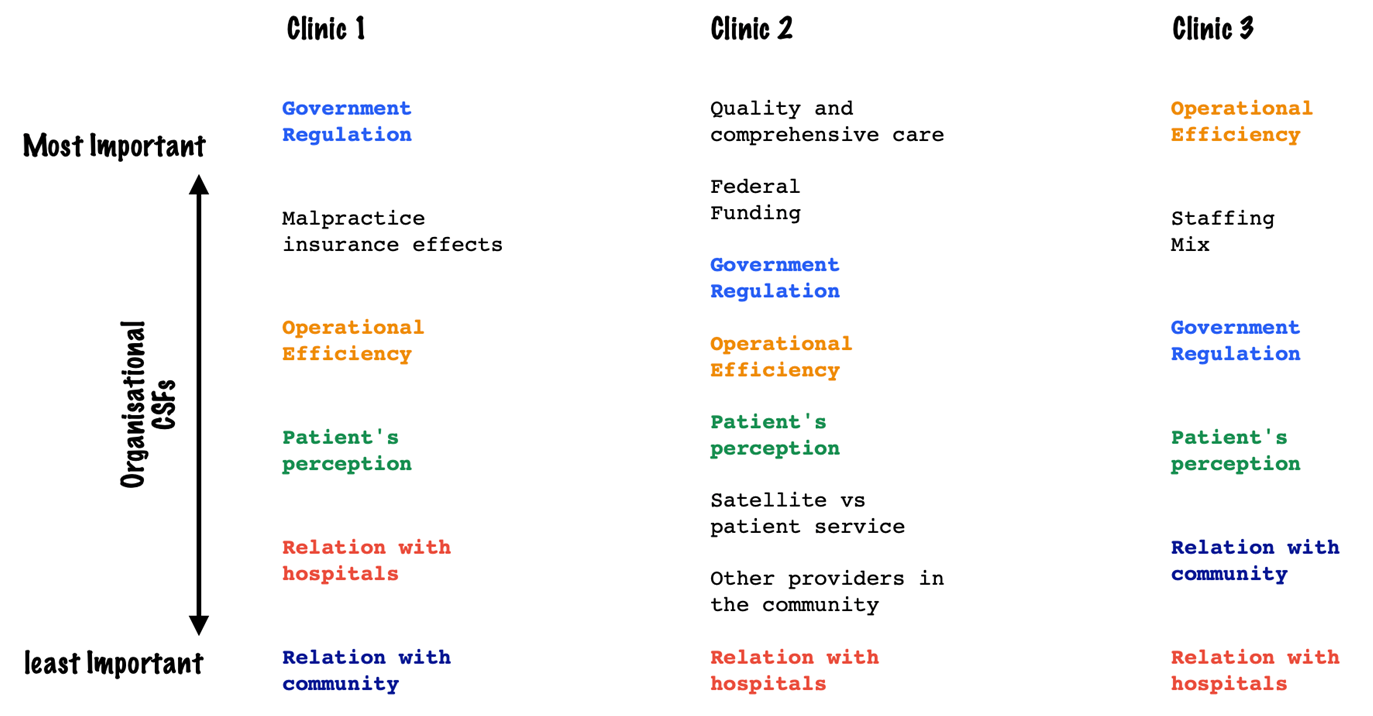

Consider the example of three clinics, the critical success factors for which are ranked in order as perceived by the respective managers:

In this example, the first clinic was mature and had been in existence for several years with a sound organizational structure with an assured patient population. Its concerns were hence limited to government regulation and environmental changes.

The second clinic’s practice was in a rural part of a relatively poor state. It was dependent on federal funding and on its ability to offer a type of medical care not available from private practitioners. Hence its number one CSF, therefore, was its ability to develop a distinctive competitive image for the delivery of comprehensive, quality care.

The third clinic was new and rapidly growing. It was heavily dependent for its near-term success on its ability to “set up” an efficient operation and bring on board the correct mix of staff to serve its rapidly growing patient population.

While many of the CSFs are common across the three clinics, each one has some unique factors that rank higher than the rest. The common factors can be explained by industry influence while the unique ones depend on the stage of growth, location, and strategy.

Sub organization CSFs

Companies can have further sub-divisions or sub-organizations within them, each of which can have its own sub-industry, environmental, strategic, and temporal conditions. The concept and the analytical process to identify such CSFs however remain the same as previously discussed.

Individual Manager’s CSFs

People at every level of the organization have individual CSFs that are influenced by role-related and temporal factors. They also depend on a manager’s strategy, objectives, goals, and CSFs from individuals and organization structure above them.

Role-oriented CSFs cut across all industries and are an integral part of the job itself and therefore persist regardless of pressures produced by other factors.

For example, manufacturing managers invariably list quality control and cost control as CSFs. CEOs will always have “Corporate Performance” in one form or another as a CSF. In performing a CSF study, it is therefore important to closely examine each individual’s role.

Sometimes, temporal factors can create unexpected CSFs for a manager. For example, the CEO of a large commercial bank would not normally review loans to developing countries. However, if the political environment in a country causes the portfolio to become risky, it could generate a CSF for the CEO.

When performing the CSF study, it is important to look at the problems and opportunities facing managers and how they deal with them. Individuals are affected by the organization’s environment and industry, but to a lesser degree.

The below example illustrates how industry, company and individual CSFs are related for an automobile manufacturer:

Uses of CSFs

CSFs serve three main purposes:

- At an individual level, they help a manager determine his/her information needs.

- They aid organizations in their process of strategic, long-range, and annual planning.

- They help organizations with information systems planning.

Using CSFs at an individual manager level

By identifying CSFs, an individual manager can benefit in several ways including:

- Determining factors on which to focus management attention – CSFs spell out the significant factors that need careful and continuous management scrutiny.

- Forcing the manager to develop good measures for factors that are critical and seek reports on each of those measures.

- Defining the amount of information that must be collected by the organization and avoiding the collection of unnecessary data which can be expensive.

- Avoiding the trap of building information reporting systems around data that is “easy to collect” and instead directing attention to data that is significant for success.

- Acknowledging the fact that some factors can be temporal, manager-specific and can constantly change. This allows developing reports as needed to accommodate changes in the organization’s strategy, environment, or organization structure.

- Treating changes in information systems as an inevitable and productive part of development rather than an indication of “inadequate design.”

Using CSFs to aid general corporate planning

Since CSFs follow a hierarchical level from the industry to corporate to sub-organization to the individual, they are highly compatible with most corporate planning processes. By designating areas in which good results must be obtained to be successful (the central idea of CSFs), organizations or individuals can consciously allocate resources in the planning process.

There are multiple use cases. For example, industry CSFs can be utilized to determine corporate strategy as they are logical and necessary inputs to corporate strategic planning which is based on an in-depth understanding of industry.

Likewise, corporate and sub-organization CSFs can be significant inputs to the short-term planning process while individual CSFs can be used by managers in developing their action plans for a given period.

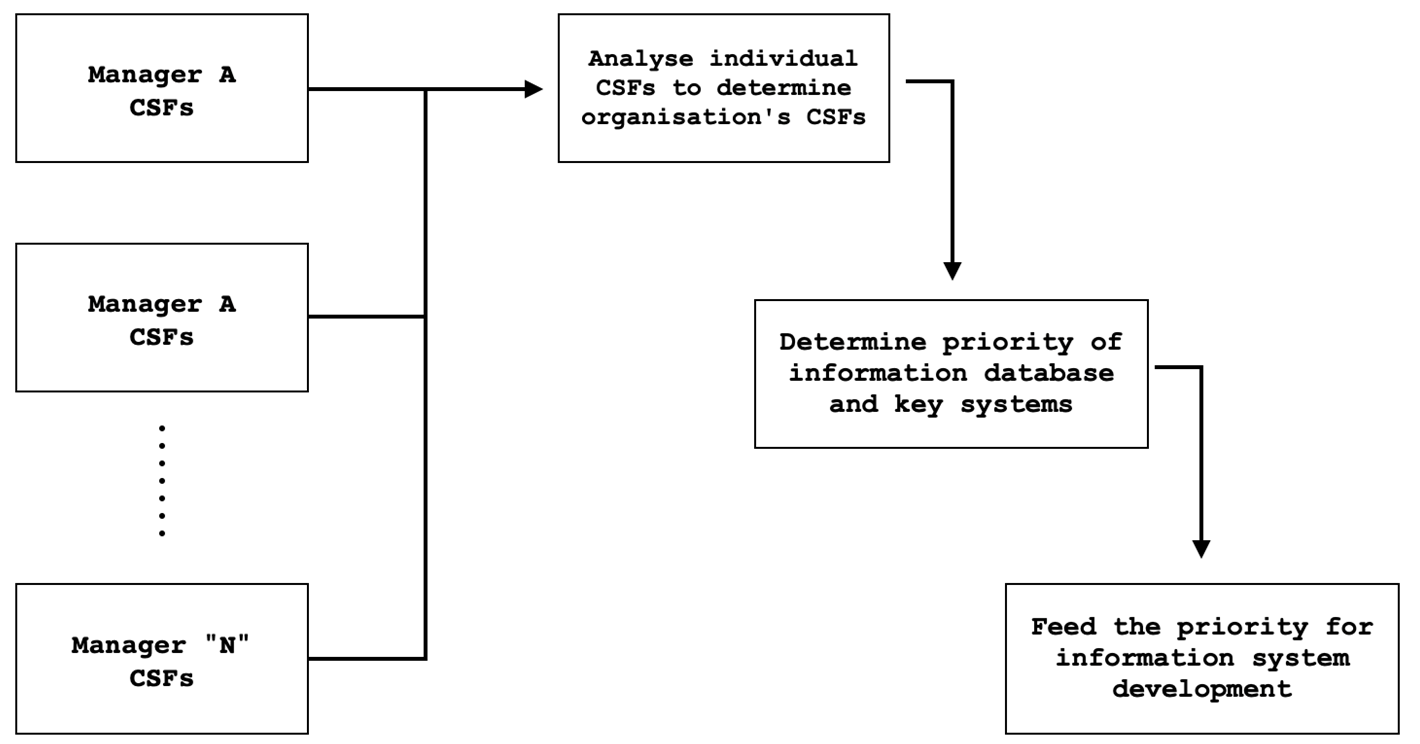

Using CSFs as an aid in information systems planning

The CSF method can be used to develop information databases with pertinent data to aid corporate decision-making. The process consists of the steps shown in the illustration:

- Step 1 – Interview managers: in the chosen organization (a corporation or a division), the top 10-20 managers are interviewed. Each manager’s CSFs are determined. If time permits, the measures used for each CSF are also determined.

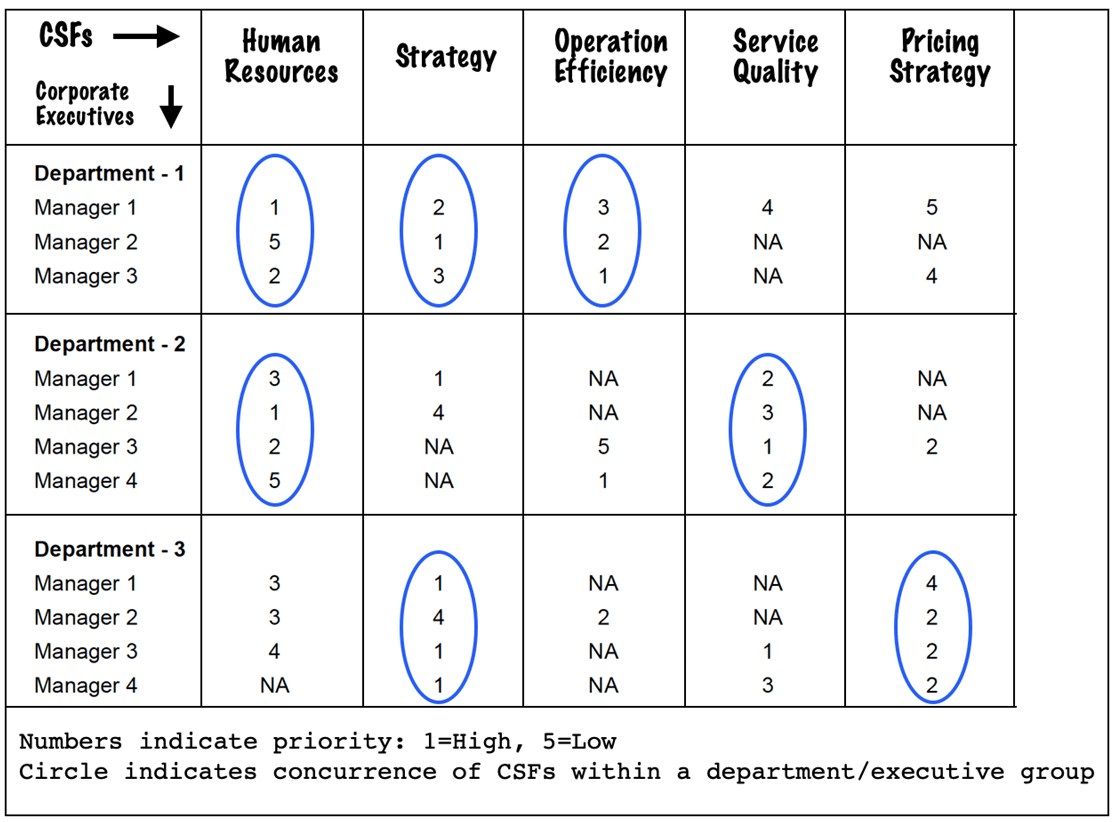

- Step 2 – Analyse individual CSFs: the results of individual CSF interviews are charted and ranked (as shown below) to determine the ones identified by multiple managers. Such CSFs provide a good approximation of the organization’s CSFs.

Chart of individual CSFs and their ranked priority in importance to each manager

Though each top manager’s job is different and individual CSFs will differ, those that repeat are usually the ones for that organization. These resulting CSFs are then checked with the organization’s management. - Step 3 – Determine priority: the organization’s CSFs identified in the previous step will indicate the need for one or more key “information databases” or “data processing systems”. Since they represent the means to satisfy the information needs of most key people in the organization, they must be given priority.

CSF ranking in the above chart, for example, indicates an information need in the area of human resources and strategy which must receive priority over operational efficiency, service quality or pricing strategy. - Step 4 – Feed the requirements into the information planning process: Once thepriorities are identified, they must be fed into the regular information systems planning process to drive the development of information systems.

Using CSFs to guide information systems development brings the following benefits:

- It provides top management with a vehicle for thinking about their information needs.

- It forces the management to focus on the planning process that goes into building information databases that support management decision-making.

- Provides a time-efficient method for planners to understand the top management’s information needs and gain insight into their view of the business. This brings significant value in developing an effective system.

Identifying CSFs through Interviews

Objectives of a CSF interview

Every CSF interviewer has a unique opportunity given the managerial time and attention made available. Merely coming out with a manager’s CSFs is not enough. The interviewer must seek to accomplish the following objectives:

- Understand the interviewee’s organization, its mission and role – the “world view” of the interviewee within the context of the organization.

- Understand the goals and objectives of the interviewee.

- Detail the interviewee’s CSFs and their measures.

- Assist the manager (interviewee) to better understand their information needs in a structured way.

- A CSF interview is also an opportunity for reverse education. Its value must not be overlooked in a hurry to collect data.

Preparing for a CSF interview

Pre-interview preparation intends to provide the interviewer with knowledge and confidence and consists of the following actions:

- Familiarize with the industry – understand the industry’s competitive forces, trends, and environment. Know the current problems, issues, and newsmakers.

- Study the company – learn about the company from publicly available sources, and through interactions with those sponsoring the CSF study. The idea is to gain insights into the company’s strategy, environment, current problems, and opportunities.

- Top-management drive – the top management must issue a communication to all interviewees explaining the purpose of the CSF study and making its commitment to the process explicit. It is also useful to include background material along with a brief outline of the interview process to help the interviewee prepare for the session.

- Define the sequence of interviews – It is ideal to start at the lowest level of management and work upwards. This provides the ability to review the knowledge gained at lower levels and become more comfortable in discussing the company and industry issues with the top management.

- Enlist a key manager – optionally, a key manager from within the organization may help the interviewer during interviews by providing an insider’s insight in discussing the interview afterward. He/she can also help clarify company-related obscure points during the interview.

Conducting the interview

With the necessary preparation out of the way, the actual CSF interview consists of the following steps:

- Opening the interview: A CSF interview must begin with a brief introductory statement of how the CSF method will be used to determine managerial information needs. If the interviewee has not read the preparatory material, it is necessary to provide an in-depth introduction to the process.

- Knowing the interviewee’s mission and role: this is often the easy way to get a manager talking and provides clues to how the manager views the world. Do they see their role as strategic and one that can induce change? Few CSFs can also emerge during such discussions. It is important to make careful notes of the interaction.

- Discussing the manager’s goals – every manager will have a set of goals on which their performance is assessed. While such goals are important, a CSF interviewer must also enquire beyond them. Sometimes unspoken and less formally stated but can expose important factors that can be key to success.

- Developing a manager’s CSFs – depending on the manager’s preparation level, determining CSFs can be quite simple or rather difficult. This step has two parts:

The first is to triangulate the manager’s CSFs through a series of questions, examples of which are:- What are the things that are currently critical to perform your job?

- What are the two or three areas where failure will hurt the most?

- If you were locked away from the company for three months, what would be the first thing you want to know when you came back?

- These simple questions can trigger interesting conversations and bring quality insights. The second part of this step is to process the manager’s response while checking the following:

- Are the CSF categories balanced enough? – for example, all or most of the CSFs stated by a manager could be internal. The interviewer must aid the manager in uncovering such oversight.

Are the CSFs aggregated? – managers can get stuck discussing the same CSFs in multiple ways. The interviewer must point out the similarity and encourage managers to think of diverse factors.

Do CSFs look beyond data? – managers tend to limit CSFs to only those factors which can be measured with hard data. It is important to stress that the CSF method is designed to elicit all information needs – soft and hard.

Understand the priority – further insights can be gained by having the manager arrange his/her CSFs in the order of priority. This later helps in deciding the organizational CSFs.

- Determine measures –measures are generally determined after the entire CSF exercise has been completed and information databases have been decided. However, during the initial CSF interview, if time permits, the interviewer can discuss ways of measuring CSFs and their possible sources.

- Are the CSF categories balanced enough? – for example, all or most of the CSFs stated by a manager could be internal. The interviewer must aid the manager in uncovering such oversight.

Analyzing the data

The data analysis step consists of two steps – review and aggregation. The review process involves looking at each manager’s CSF to check if they evenly cover the classification and dimensions discussed earlier in this article. For example, a manufacturing manager’s CSFs must include quality, costs, and inventory control.

It is also important to check if the collected CSFs fit a pattern that is consistent with the common perception of problems, opportunities, industry structure, current competitive conditions etc. Major gaps, if any, must be brought up in a subsequent review meeting with the manager.

Once the target executive’s CSFs are reviewed, they must be aggregated using the steps discussed earlier (in using CSFs as an aid in information systems planning).

The output of this exercise provides the most important factors that must go into the design of an information database. Once the management agrees to develop the database, the second phase of interviews begins. Here the emphasis switches from identifying CSFs to determining each manager’s measures and the data needed for those measures.

This way, the CSF method helps build the necessary data structure for the information needs of the organization that is consistent with its decision-making priorities.

Sources

1. “Five Fundamental Questions To Help You Determine Your Critical Success Factors”. Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2019/10/31/five-fundamental-questions-to-help-you-determine-your-critical-success-factors/. Accessed 14 Aug 2024.

2. “Chief Executives Define Their Own Data Needs”. John F. Rockart (Harvard Business Review), https://hbr.org/1979/03/chief-executives-define-their-own-data-needs. Accessed 14 Aug 2024.

3. “Business systems planning (BSP)”. HandWiki, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/28412. Accessed 21 Aug 2024.

4. “A primer on critical success factors”. Christine V. Bullen and John F. Rockart, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5175561_A_primer_on_critical_success_factors. Accessed 21 Aug 2024.

5. “TSMC is making the best of a bad geopolitical situation”. The Economist, https://www.economist.com/business/2023/01/19/tsmc-is-making-the-best-of-a-bad-geopolitical-situation. Accessed 20 Aug 2024.

6. “Boeing 737 Max: why was it grounded, what has been fixed and is it enough?”. The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/boeing-737-max-why-was-it-grounded-what-has-been-fixed-and-is-it-enough-150688. Accessed 20 Aug 2024.

7. “The key variables in planning and control in medical group practices.”. MIT Libraries, https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/17137. Accessed 21 Aug 2024.