The business world today is more interconnected than ever. From supply chains to the flow of information, everything is going through rapid, unpredictable, and unprecedented change.

The digital revolution has enabled firms to leverage data and connectivity to make rapid decisions, but it has also increased the potential for large-scale failure and security breaches with cascading consequences. From structural shifts presented by climate change to uncertain geopolitical situations, firms today must operate in a world where the future is uncertain, and change can come fast.

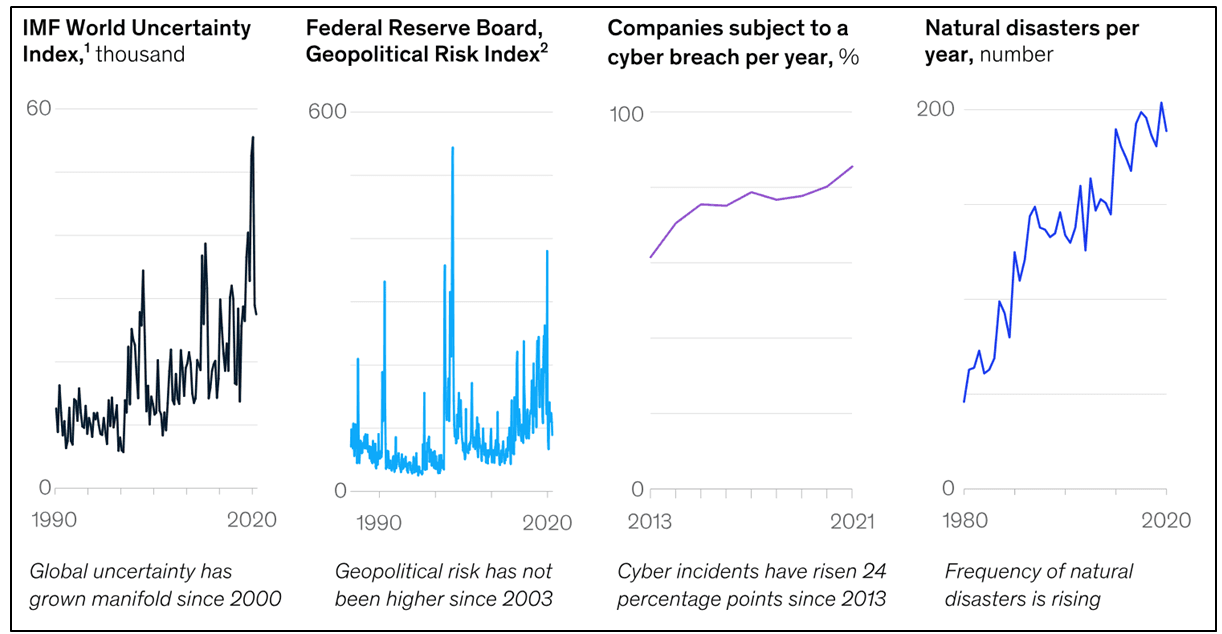

A study by McKinsey predicts that catastrophic events will become more frequent while less predictable – they will unfold faster and in more varied ways:

Despite growing risks, however, most companies have remained persistently focused on near and medium-term earnings, typically assuming smooth ongoing business conditions. In the backdrop of a volatile future, it is thus important for firms to build resilience to ensure business continuity.

Business Contingency Planning (BCP) is a way to mitigate the impact of adverse events by developing a strategy that outlines the steps teams must take in the event of a crisis. BCP is essentially the backup plan – the ‘Plan B’ that goes into action when the worst-case scenario occurs. The goal of BCP is to help a business stay up and running after a predictable but unlikely disaster has occurred.

Role of contingency plan in business

Contingency planning is part of a much broader field of management known as Business Continuity Management (BCM) – the goal of which is to ensure that the business continues to operate (or recovers quickly) following a disaster or an adverse event.

As goalposts have moved towards operational and business resilience, organizations have taken a holistic approach to BCM by expanding it to include operational risk management, disaster recovery, contingency planning, insurance aspects, security, regulatory compliance, financial risk management, asset protection, supply chain and more. While these functions are not necessarily integrated, they are interdependent and have blurred boundaries.

Contingency plans are developed to handle specific emergencies and deal with specific threats. They are designed to respond to the initial stages of identified risks and are implemented by front-line managers to respond to such risks occurring within their areas of responsibility.

Steps in contingency planning

1. Mapping the Risks

Contingency plans address critical events that could potentially place employees at personal risk (whether physical or psychological), threaten the integrity of critical infrastructure, lead to the loss of sensitive materials or information, hinder the operational productivity of a project, or present a threat to the business interests and reputation of the company.

Hence, contingency planning always begins with risk identification:

Identify sources of risks

The concept of risk is often complex, subjective, and fluid. Any phenomenon that either directly or indirectly affects a business or its employees in terms of productivity and safety is a risk. For practical purposes, risks can be categorized into:

- Personnel Risk – Those in management roles have access to sensitive information. Risk can arise if proper due diligence is not conducted. Sensitive information can leak into the hands of competitors or adversaries.

- Competitive Risks – Business activities are at risk if companies do not take cognizance of how competition is strategizing their activities. Investigative services and analysis can provide insights into new market threats that might emerge with time.

- Due Diligence Risk – a company must be confident that its client, partner, or subcontractor is appropriate in terms of closing deals involving legal, liability, or capital investments. Investigative services can ensure that companies are reputable and appropriate to engage with.

- Reputation Risk – Brands and reputations underpin the status and reliability image of a business; therefore, damage to either brands or a company’s reputation can undermine its commercial productivity.

- Information Risk – While information technology enhances productivity, it can also leave companies vulnerable to data theft or loss. Industrial, criminal, government or terrorist espionage has serious implications for businesses.

- Intellectual Property Risk – Commercial espionage or organized crime poses a serious threat to established products as well as emerging markets. Intellectual property is vulnerable to theft or replication, which can undermine the value of the producer’s performance.

- Physical Risk – crime, insurgency, terrorism, civil unrest, and natural disasters are unpredictable and have significant impacts on companies and individuals.

- Political Risk – Political instabilities can have a considerable impact, especially on firms with a global presence. The analysis and assessment of opaque and uncertain political environments is important to navigate complex political environments.

Identify critical dependencies

The risks identified can affect critical dependencies such as:

- Power and Utilities – risk exposures might result from the disruption to power and other utilities on which the company, its activities, or its personnel are dependent.

- Supply chain assurance – business disruptions might occur if critical materials and supplies are delayed, damaged, or stolen – in terms of safety and security as well as business performance. (Example: Chip shortages induced by the pandemic [2])

- Critical Materials or Structures – risks that might be present if critical structures, facilities, or materials are lost, damaged, or stolen. This also includes assets that the company owns which if affected could significantly disrupt business.

- Employee Confidence – implications of a loss in employee or workforce confidence should they be exposed to risks that undermine their ability or willingness to work.

- Vendor or partners Performance – the degree of dependence a company has upon vendors or partners should they be affected by risks or disruptions that might indirectly affect the company.

- Governance – governance and social stability within an operating region are important components of operational success.

- Technology and Information – risk implications and impacts should technologies be damaged, corrupted, lost, or stolen either from the company or from its clients or vendors.

As a part of contingency planning, organizations must look through the lens of each of these critical dependencies and analyze how the risk affects them.

Perform tactical risk evaluation

Risks are fluid and can change rapidly due to unforeseen circumstances. Their evaluation can be complex and subjective. Mapping risks helps identify their impacts and likelihood. Some of the strategies to evaluate are:

- Hard and Soft Targets – is the company an easy target compared to similar businesses or operations within the region, or are hostile groups more likely to achieve success focusing on less protected companies?

- Common or Unique – are certain risks common within a particular environment, or would they be considered unique or unusual if they were to occur?

- Incentives and Objectives – what are the incentives and objectives of hostile individuals or groups? What are they trying to achieve, and how might they best achieve their goals?

- Capabilities and Trends – what are the realistic capabilities of hostile groups—do they have the knowledge, technology, and funding to be successful, or are they unable to launch sophisticated attacks? Do any trends support this analysis or suggest future risks?

- Mitigation Reliability – what mitigation measures have been created to deal with risks against the company or its personnel? What gaps remain, and how effective are the measures? Should gaps then be addressed or only acknowledged?

- Impact Evaluations – what impacts will be associated with an incident, both to the company and its personnel, as well as to surrounding areas and the populace? Consider the holistic impacts and ramifications of each risk type. Also, how does this impact teammates and subcontractors?

- Tolerances – what tolerances does the company have, as well as the pertinent government, population, and legal systems? How much risk will be accepted by each group, and where do tolerance-level risks get breached?

- Response Capacity – what response measures and capabilities are available to deal with a crisis? Do the government or supporting bodies have the knowledge, resources, and interest to assist the company, or will they be part of the problem? What outsourced and in-house capacities are available and might be brought to bear?

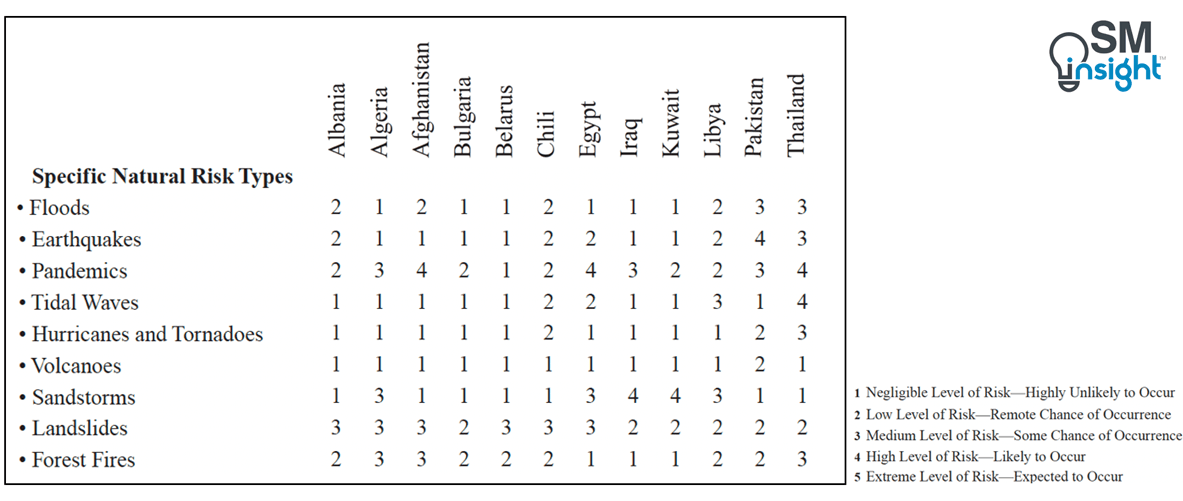

Shown below is a simple risk mapping table that helps gain a picture of natural calamity risk probabilities for a range of countries. It is relatively easy to maintain and provides a mechanism for guiding management decision-making.

Such risk evaluations must be supported by current intelligence and threat evaluations and should be kept alive.

Define risk tolerance

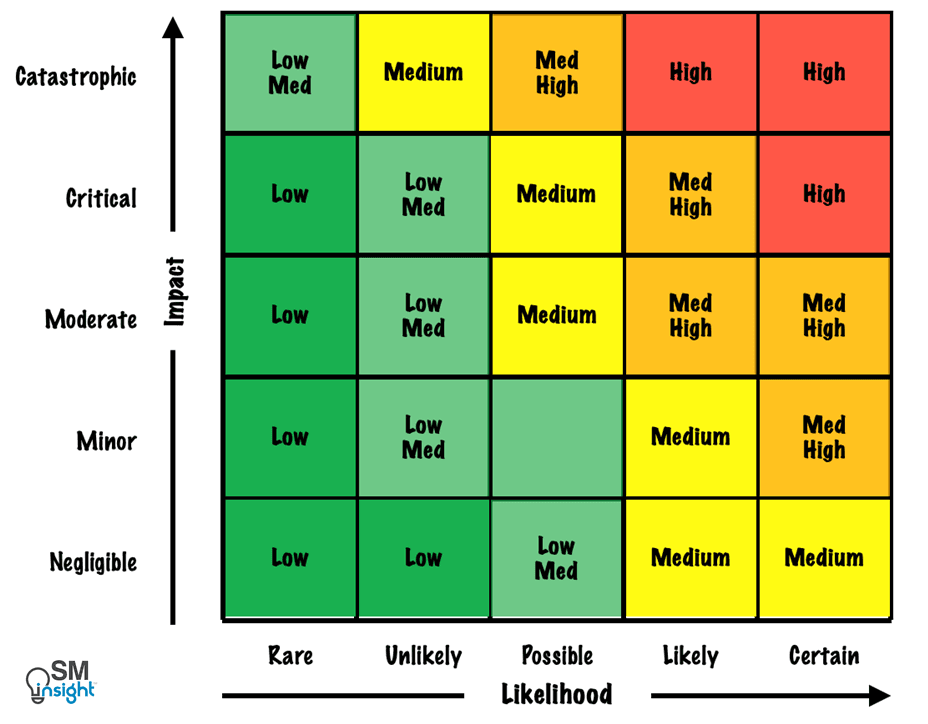

Since individual perceptions and opinions about risks can vary, it is important to define what constitutes a low, medium, high, and extreme risk. This helps avoid ambiguity and brings a consistent approach within a company.

This can be achieved by plotting risks on a risk profile matrix that considers both, impact and likelihood:

Not all risks need a risk management plan. However, those in the red and orange zones of the risk profile matrix must receive priority and have a well-defined action plan.

Identify triggers

Like with risk tolerance, individual perspectives on when a problem becomes a crisis can vary and delay critical response time. It is important to have documented identification of trigger points that spell out when a problem has become a crisis and at what level the crisis is rated.

2. Perform Business Impact Analysis (BIA)

Not all activities performed by a business are equally important. Some are “time critical” and can severely impact the business immediately while others can wait. In the event of a major disruption, activities that have a very low tolerance for disruption must be given priority. They must also receive more attention during the contingency planning process.

A BIA helps businesses pinpoint such processes and involves the following steps:

Identify important business functions

The process begins by making a list of all major organizational functions that support the performance of the organization’s mission. This list must include:

- A description of each function in basic terms.

- Requirements to perform each function (manpower, critical infrastructure, utilities, assets etc.)

- Products or services delivered or actions produced by each function

Some of the methods for identifying business functions include desk review of documentation, questionnaires, interviews, workshops, study of process flows and a review of outputs and deliverables.

Separate the essential functions

From the list of functions identified, separate the truly essential ones from the normal. Only those functions which an organization must perform even during a disruption to normal operations are seen as essential.

The following questions help in assessing if a function is critical:

- What is its true cost to the organization if the function is disrupted?

- How does it impact the organization’s survival?

- How does it impact mission achievement?

- How does it impact the organization’s image?

- What is the financial impact?

- How does it impact the most important customers, deliverables, and services?

- Is it time-critical?

- Does it stop a mission-critical function?

- Could the customer (or user) cope without it?

- Do alternatives exist that could potentially achieve the same (or acceptable equivalent) deliverables?

Essential functions are both important and urgent. Once identified, the list must be presented to leadership for review and concurrence.

Assess the impact of risks on essential functions

Each of the critical risks identified in Step 1 must be studied for its impact on essential functions. Organizations must answer the following questions:

- What is the vulnerability of each essential function vs the risk identified in Step 1?

- What would be the impact if the essential function performance is disrupted?

- What is the timeframe for unacceptable loss of functions and critical assets?

Factors such as lost/delayed sales and income, increased expenses (e.g., overtime labor, outsourcing, expediting costs, etc.), regulatory fines, contractual penalties, customer dissatisfaction or defection, and delay of new business plans must be considered while assessing the impact.

It is also important to consider various scenarios for each risk, ranging from medium to worst. For example, if a hurricane has been identified as a hazard, it is also important to identify that it is a Category 3 or higher hurricane, lasting two days or more, etc.

Such information can be based on historical patterns (typical duration) and general predictions of the effect on the community, as well as likely effects on the organization. Alternatively, for low-frequency risk events where historical data is not readily available (e.g. bombing), general assumptions can be made about the likely characteristics and effects.

3. Develop response plans for each scenario

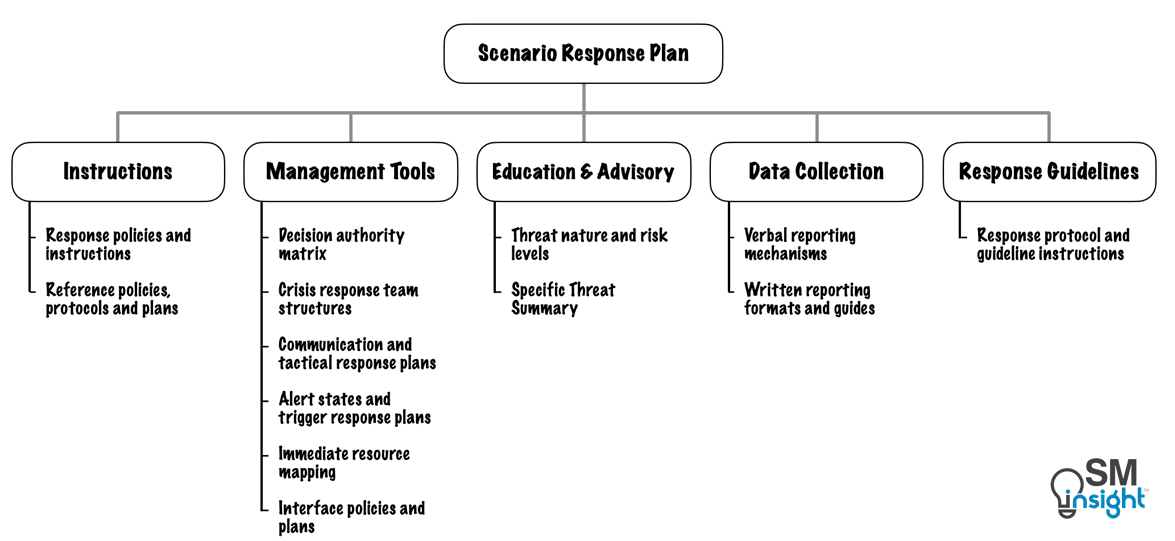

Response plans are a collection of procedures and information intended to avoid or minimize the impact on critical activities in the event of a disruption. While they can vary based on business function and the nature of risk, the general structure is as shown:

Instructions

Scenario response plans are designed to allow both first responders as well as managers to understand the risk natures and response measures appropriate to their context. They must provide logical and user-friendly response guidelines and information capture formats to support pragmatic incident management during a risk scenario.

Policies that are part of instructions must be designed considering the level of experience and capability of those implementing the plan. Clarity and comprehensive details are important when crisis management experience is limited.

Consistency must be maintained in formats and structure so that personnel moving between projects become familiar with how the plan is laid out and how it works.

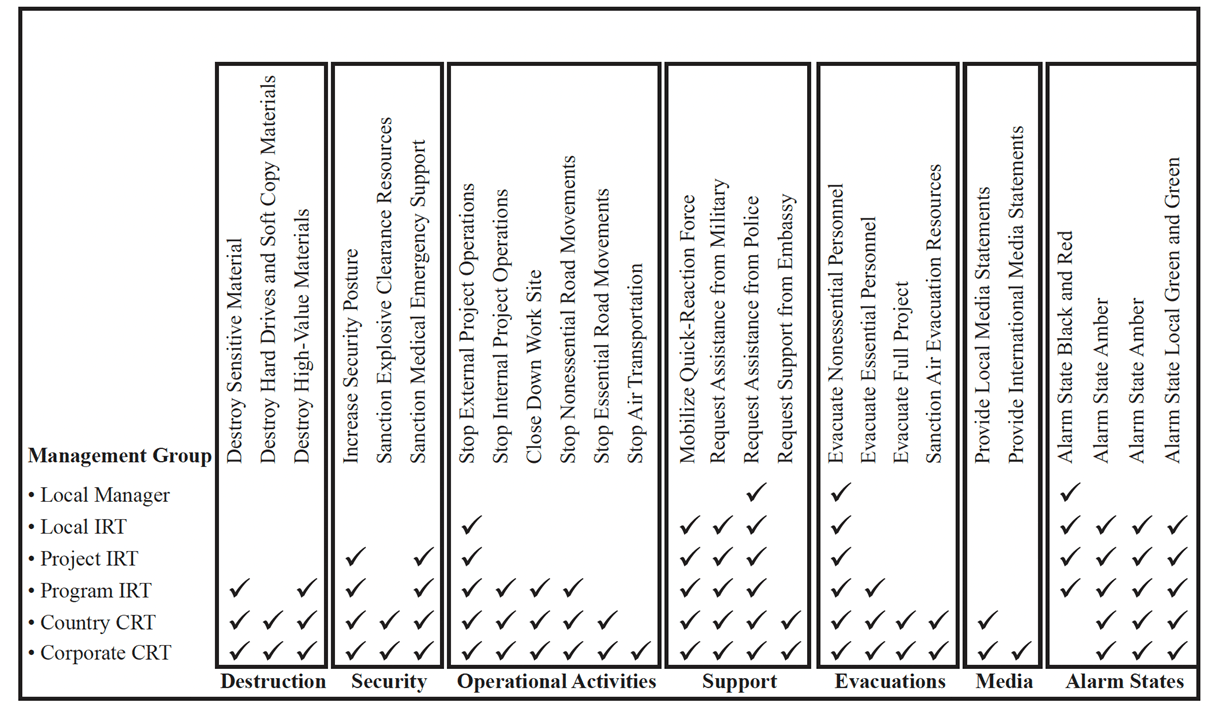

Management Tools

- Decision Authority Matrix: response plans must include references to the decision authority matrix. This guides incident managers in determining what permissions they have, as well as whom they should contact to receive authority to make more impactful or strategic decisions:

- Crisis response team: having a well-defined crisis response team structure helps in coordinating activities during an emergency, both internally as well as managing and interacting with external groups, individuals, and agencies.

A crisis response team may consist of:- Crisis management team commander

- Crisis team coordinator

- Physical security manager

- Technical security manager

- Special response team leader

- Administrative manager

- Intelligence/information officer

- Liaison officer (Liaison with authorities and govt. bodies)

- Communications Officer

- Public relations officer

- Legal counsel

- HR

- Health and Safety officer

- Finance and investment relations

- Alert states and triggers: Since the difference between a problem and a crisis can be subjective, those less experienced need clear guidelines in identifying and managing crisis events. This also ensures managers don’t ignore a real crisis event, or conversely do not mobilize resources that far exceed requirements.

While alert states are generally defined as a part of a broader risk management plan, scenario response plans can use threat-specific simplified versions. Incident managers must also be provided training and instructions on how to sensibly and effectively escalate a risk management posture to reflect threat indicators or rising levels of threat. - Immediate resource mapping: providing succinct resource mapping ensures managers are quickly directed to the most appropriate and reliable internal and external resources to help them best manage a crisis.

Resource mapping should identify both usable and unavailable resource options to avoid time wasted in pursuing those that are unreliable or unavailable. Immediate resource mapping may cover a range of service areas, including but not limited to:

– Critical commercial support (utilities, power, medical, security, legal, etc.)

– Emergency materials and resources

– Transportation services

– Medical, including stress and trauma support

– Evacuation support and repatriation services

– Legal services

– Firefighting and emergency services

– Security and guard services

– Liaison and interpreter support - Interface policies and plans: having separate interface plans can ensure more accurate and timely information flow between the company and external groups, improving decision-making and overall event awareness for a project team, as well as corporate officers.

Education and Advisory

Education and advisory help create the conditions where individuals and groups feel confident to meet the unique challenges of a risk scenario. The following forms of education and training help develop the skills and capabilities of an organization’s crisis leaders:

- Formal Instructions – focused training course for crisis leaders on risk and security management issues conducted in modules or as a condensed package.

- Mentoring Programs – trained crisis leaders can mentor less experienced team members to enable cross-pollination of skills and knowledge. This can be conducted in either formal or semiformal setups.

- Shadowing and transitioning – crisis leaders may delegate or transition responsibilities over a defined period to ensure that new crisis leader incumbents have a period of indoctrination before fully assuming responsibilities.

- Tabletop Exercises – management leadership exercises and discussions can be used to run a crisis management team, and individuals, through their paces as a low-cost, high-value training medium.

- Discussion groups – working groups or forums can provide a valuable medium whereby information and ideas are shared, and friction points or shortfalls are identified and resolved.

- Instructional manuals – can be used (often in conjunction with other education and training mediums) to educate crisis leaders on their role, as well as how an organization will function and respond to a crisis.

- Web-based training – can be used to meet the needs of a dispersed crisis management team.

- Train the trainer – internal capability can be enhanced by improving the knowledge and capabilities of the instructor while also creating a pyramid effect of capability within a wider group.

- Activation exercises – can be used to determine the ability of individuals and the crisis management team to effectively respond to a crisis event. This tests both the mechanisms for activation, as well as the competence of individuals and the wider group in terms of response.

There is no miracle answer for how crisis leadership should work, nor is there a way to predict or assess whether the individual or group leadership approach used was the most effective one. Establishing a solid platform from which good decisions can be made should be the principal goal of companies and organizations.

Data collection

In the event of a crisis, verbal as well as written communication is crucial to deliver clear and factual information for effective decision-making and resource mobilization.

Scenario response plans must thus include data collection forms that match the risk types determined during risk analysis. This could include templates that provide a simple, quick, and effective method for both untrained and experienced professionals to disseminate information.

Response guidelines

Since scenario response plans apply to a wide range of audiences, when formulating guidelines, companies must consider the needs of the lowest level of responder competence. Such guidelines should be well thought out from the point of view of a first responder and make use of logical methodologies and considerations for bringing a crisis event under control.

In general, guidelines should be clear, simple, and as succinct as possible. They must provide a checklist of actions to take and options to consider during a crisis. Tabulations must be used wherever possible so that responders can quickly move to the section pertinent to a specific event they are dealing with, rather than having to sift through volumes of non-applicable information during an emergency.

4. Test and update regularly

To be effective, BCPs must be maintained in a ready state that accurately reflects current requirements, procedures, organizational structure, and policies. Changing business needs, technology upgrades, or new internal or external policies can bring new challenges.

BCPs must be a part of the organization’s change management process to ensure that contingency measures are revised as required. This includes maintenance, producing ongoing updates to security plans, security assessment reports, and plans of action and milestone documents.

While the frequency of periodic reviews must be defined, significant changes should also trigger a review of elements of the plan that could be impacted. At a minimum, plan reviews should focus on the following elements:

- Operational requirements

- Security requirements

- Technical procedures

- Hardware, software, and equipment (types, specifications, and amount).

- Names and contact information of team members.

- Names and contact information of vendors, including alternate and offsite vendors.

- External point of contact in case of emergency.

- Alternate and offsite facility requirements.

- Vital records – both electronic and hardcopy formats.

Changes made to the plan, strategies, and policies should be routed through a designated coordinator, who should communicate changes to relevant stakeholders. The coordinator must record plan modifications using a record of changes, which lists the page number, change comment, and date of change:

| Record of Changes Title of document: Document No : | ||||

| Page No | Change Comment | Date of Change | Authorized by | Signature |

The designated coordinator must enforce strict version control by requesting old plans or plan pages in exchange for new plans or plan pages. While this is easily achieved in the soft form of documents, ensuring updates to hard copies can be difficult but critical.

While certain changes to BCP may be quite visible, others will require additional analysis. The goal is to ensure that the plan accurately reflects recovery priorities and concurrent changes.

5. Make BCP a part of the organization’s culture

Business leaders must see the value of having a strong BCP in place and look at the big picture – not just the cost of the plan but the potential costs incurred if no plan is put in place. Through a combination of awareness and training, BCP must be made a part of the organization’s culture.

Some of the mechanisms to raise awareness include:

- Involving staff in the development of the organization’s contingency planning strategy.

- Written and oral briefings.

- Learning from internal and external incidents.

- Discussion based exercises.

It is equally important to make contingency awareness a part of the induction process for new employees.

Example of high-level contingency planning in supply chain

Supply chains today involve complex dynamics and are made up of thousands of interconnected parts and participating members. The pandemic has shown how fault-prone and vulnerable they can be.

When participating members of the chain interact autonomously, it can result in numerous states on the local as well as the supply chain level that require active risk management strategies.

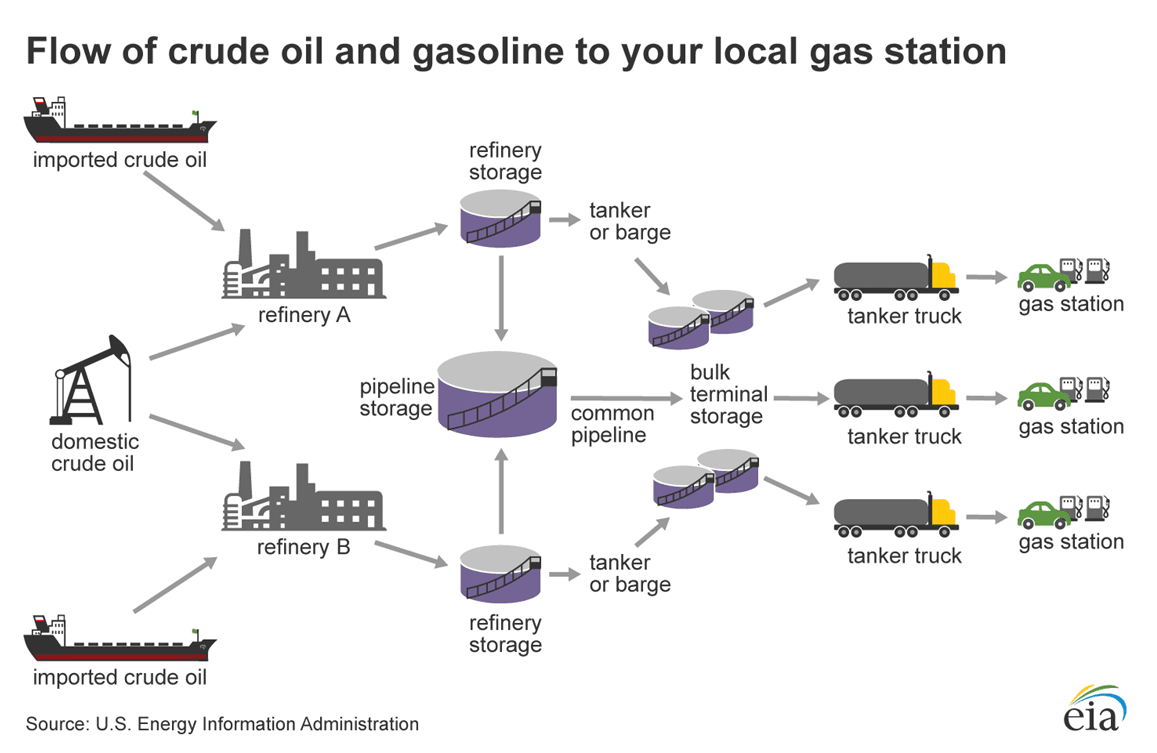

Take the petroleum supply chain, which is divided into two major areas: upstream and downstream. The upstream comprises crude oil exploration, production, and transportation while the downstream involves product refining, transport, storage, distribution, and retail:

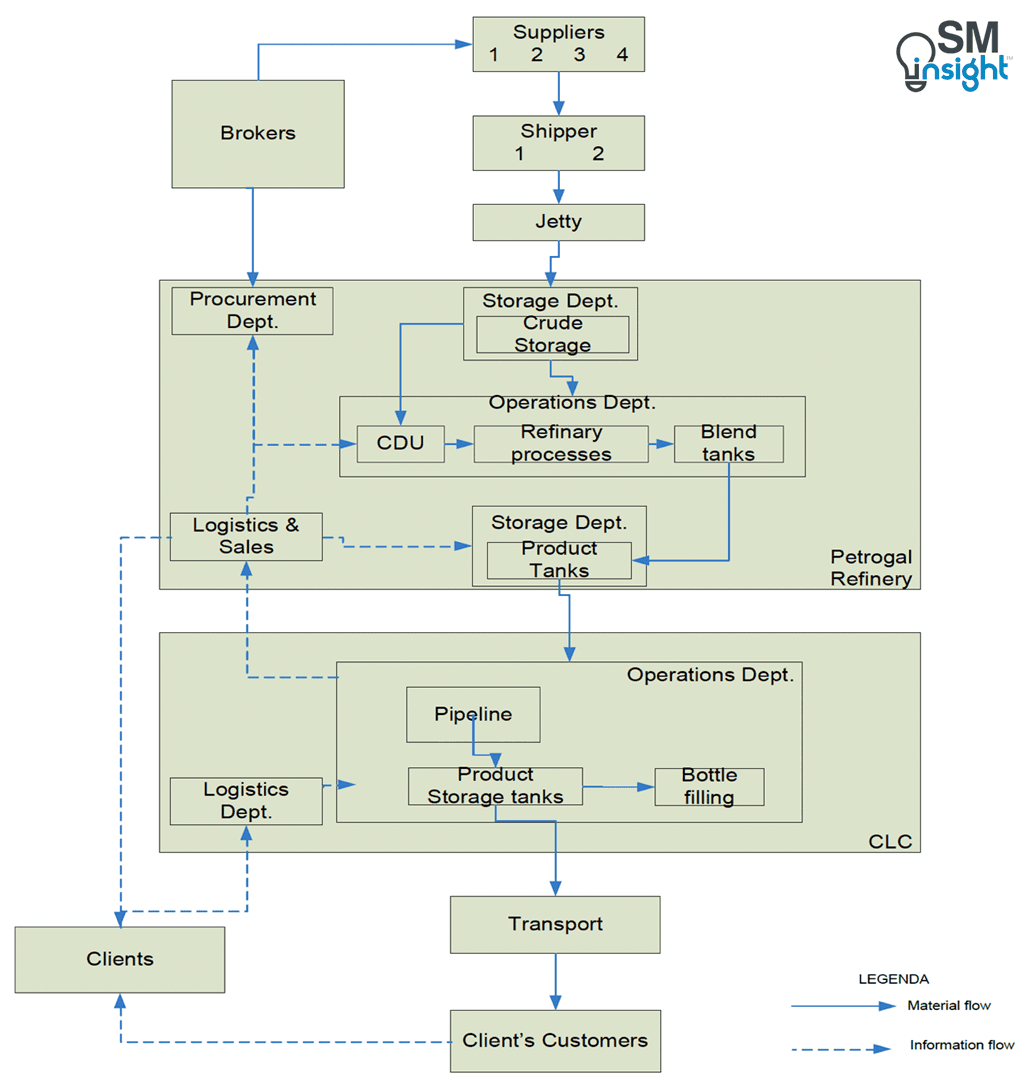

The importance of contingency planning in the downstream petroleum supply chain is well understood and implemented. In Portugal, for example, the major petroleum companies, their suppliers, clients’ facilities, systems, and processes are intrinsically interlinked to form an extended petroleum supply chain as shown:

The system uses a concept known as the Supply Chain Event Management (SCEM) [5] to trigger contingency planning, some real case examples of which are as presented:

| Disruption Mode | Trigger / Impact | Contingency Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Supply-side | Product shortages / can lead to unmatched orders and lower profits | Use measures including inter-company exchanges of products. Optimize replenishment schedules to prioritize stocking of the product in shortage. Other strategic reserve capacity measures. |

| Supply-side | Product out of specification / can block up to 25 million storage capacity per tank. | Put an immediate hold on the contaminated lot. Do not receive any further quantity. Expedite stock to industries with lower product specification needs. Supply-demand from alternate facilities. Meet with suppliers and clients to redesign the contingency plan. |

| Transportation | Rupture in Pipeline / can lead to prolonged in-operation of the supply chain. | Cater to the demand from alternate facilities. Have backup contracts in place for road transport. Design contingency plans with suppliers and clients. |

| Facilities | Safeguard system out of order / unsafe operation | Switch to manual mode operation Activate strict manual checks Order immediate repair services Evaluate potential dangers and alternative renovation requirements. |

| Information Systems | Failure of information systems / inability to fulfil customer order | Activate redundant systems. Identify problem area, activate maintenance contract. Gather sourcing information for alternate system in the worst-case scenario. |

| Communications failure | Infrastructure failure due to fiber optic interruption | Activate backup lines. Localize interruption and immediately mobilize maintenance team. Activate alternate communication measures (Example: wireless) |

| Exceptional Demand | Demand exceeds capacity due to increased air traffic or heating necessity a harsh winter | Optimize replenishment schedules. Increase production shifts. Activate alternative supplies. |

Thus, contingency planning helps companies better prepare to navigate a turbulent world where adverse events can range from ordinary, predictable risks to black swan events such as the pandemic. Having a good contingency plan is about preparing today for tomorrow’s problems.

Sources

1. “The resilience imperative: Succeeding in uncertain times”. McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/risk-and-resilience/our-insights/the-resilience-imperative-succeeding-in-uncertain-times Accessed 15 Sep 2024.

2. “Global chip shortage”. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_chip_shortage Accessed 15 Sepn 2024.

3. “Business Continuity Management”. Michael Blyth, https://www.amazon.com/Business-Continuity-Management-Building-Effective/dp/0470430346 Accessed 15 Sep 2024.

4. “Gasoline explained Where our gasoline comes from”. U.S. Energy Information Administration, https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/gasoline/where-our-gasoline-comes-from.php Accessed 16 Sep 2024.

5. “Supply Chain Event Management”. Lorena Andrea, Bearzotti Erica, Fernández Armando, Guarnaschelli Hector, Enrique Salomone, Omar Chiotti , https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221916126_Supply_Chain_Event_Management_System Accessed 17 Sep 2024.

6. “Contingency Planning: A literature review”. Leão José Fernandes and Francisco Saldanha da Gama, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230807504_Contingency_planning_-_a_literature_review Accessed 17 Sep 2024.

7. “The Business Process Analysis (BPA) and a Business Impact Analysis (BIA) Users Guide”. Federal Emergency Management Agency, https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/fema_BPA-BIA-Users-Guide_070119.pdf Accessed 19 Sep 2024.

8. “Contingency plan examples: A step-by-step guide to help your business prepare for the unexpected”. IBM, https://www.ibm.com/blog/contingency-plan-examples/ Accessed 19 Sep 2024.

9. “Business Continuity Management: Global Best Practices”. Andrew N Hiles, https://www.amazon.com/Business-Continuity-Management-Global-Practices/dp/1931332355 Accessed 19 Sep 2024.

10. “Business Continuity Management Toolkit”. HM Government, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7b283de5274a34770e9d01/Business_Continuity_Managment_Toolkit.pdf Accessed 20 Sep 2024.

11. “About CLC”. CLC, https://www.clc.pt/clc/ Accessed 20 Sep 2024.